Ways of Seeing Animals Documenting and Imag(In)Ing the Other in the Digital Turn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jurassic Park" Have Come to Pass

JURASSIC WORLD and INDOMINUS REX 0. JURASSIC WORLD and INDOMINUS REX - Story Preface 1. EARLY DINOSAUR DISCOVERIES 2. THE JURASSIC PERIOD 3. JURASSIC-ERA DINOSAURS 4. FOSSILIZED AMBER 5. THE SOLNHOFEN LIMESTONE 6. TYRANNOSAURUS REX 7. T-REX - SUE 8. PTERANODON 9. TRICERATOPS 10. VELOCIRAPTOR 11. SPINOSAURUS 12. DINOSAUR TRACKS AND DISPUTES 13. NEW DINOSAUR DISCOVERIES 14. JURASSIC WORLD and INDOMINUS REX What do you do when you want to boost visitor attendance to your dinosaur-dominated, Jurassic World theme park? Use DNA, from four different dinosaurs, and “in the Hammond lab” create something entirely new and fearsome. Then ... give the new creature a name which signifies its awesome power: Indominus rex. At least ... that’s how the story theme works in the 2015 film “Jurassic World.” So ... let’s travel back in time, to the age of the dinosaurs, and meet the four interesting creatures whose DNA led to this new and ferocious predator: Rugops; Carnotaurus; Giganotosaurus; Majungasaurus. If—contrary to plan—Indominus rex becomes a killing machine, we have to ask: Did she “inherit” that trait from her “ancestors?” Let’s examine the question, starting with Rugops (ROO-gops). What we know about this theropod, from a physical standpoint, comes from a single, nearly complete and fossilized skull. With its weak but gaping jaw and skull, Rugops—which means “wrinkle face”—is not a predator like the Cretaceous-Period Spinosaurus. Instead, Rugops is a natural-born scavenger, likely waiting in the wings for what’s left of a Spinosaurus-caught, Cretaceous-era fish known as Onchopristis. Living off the scraps of meals, killed by another creature, could be enough for a Rugops. -

Educator Guide Spring 2020 February - June

Educator Guide Spring 2020 February - June Looking for ways to make learning come to life? Let us help you! The Milwaukee Public Museum is the most exciting field trip destination in the region, an educational experience that will last far beyond the visit with your students. We have many free resources that can supplement your field trip experience before, during, and after your visit to foster a deeper engagement with your students and your curriculum. 1 EDUCATOR GUIDE | Fall 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome . 2 Contact Information . 3 Pricing . 3 Planetarium Programs . 3 Theater Offerings . 4 Education Investigations . 5 Exhibit Tours . 6-7 Early Learning . 7 MPM on the Move . 8 Educator Benefits & Resources . 9 Planning Your Visit . 10 Welcome Dear Educator, Welcome to the Spring 2020 semester! We hope that this Educator Guides finds you well. As you will see in the pages to follow, MPM has a lot of unique educational opportunities for your students. Please check our outreach program, MPM on the Move, and explore ways we can bring the Museum to your classroom. Coming to MPM for a field trip? Enhance your students’ learning with programs led by our talented educators and docents. It is our hope that this guide serves as a tool to assist you in creating meaning and memorable experiences for your students. We look forward to working with you and your school this year! Take care, Meghan Schopp Director of Education and Public Programs 2 EDUCATOR GUIDE | Fall 2019 CONTACT INFORMATION By Phone: Call 414-278-2714 or 888-700-9069 Field Trip Call Center Hours: 9 a.m. -

General Vertical Files Anderson Reading Room Center for Southwest Research Zimmerman Library

“A” – biographical Abiquiu, NM GUIDE TO THE GENERAL VERTICAL FILES ANDERSON READING ROOM CENTER FOR SOUTHWEST RESEARCH ZIMMERMAN LIBRARY (See UNM Archives Vertical Files http://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmuunmverticalfiles.xml) FOLDER HEADINGS “A” – biographical Alpha folders contain clippings about various misc. individuals, artists, writers, etc, whose names begin with “A.” Alpha folders exist for most letters of the alphabet. Abbey, Edward – author Abeita, Jim – artist – Navajo Abell, Bertha M. – first Anglo born near Albuquerque Abeyta / Abeita – biographical information of people with this surname Abeyta, Tony – painter - Navajo Abiquiu, NM – General – Catholic – Christ in the Desert Monastery – Dam and Reservoir Abo Pass - history. See also Salinas National Monument Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Afghanistan War – NM – See also Iraq War Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Abrams, Jonathan – art collector Abreu, Margaret Silva – author: Hispanic, folklore, foods Abruzzo, Ben – balloonist. See also Ballooning, Albuquerque Balloon Fiesta Acequias – ditches (canoas, ground wáter, surface wáter, puming, water rights (See also Land Grants; Rio Grande Valley; Water; and Santa Fe - Acequia Madre) Acequias – Albuquerque, map 2005-2006 – ditch system in city Acequias – Colorado (San Luis) Ackerman, Mae N. – Masonic leader Acoma Pueblo - Sky City. See also Indian gaming. See also Pueblos – General; and Onate, Juan de Acuff, Mark – newspaper editor – NM Independent and -

Critical Animal Studies: an Introduction by Dawne Mccance Rosemary-Claire Collard University of Toronto

The Goose Volume 13 | No. 1 Article 25 8-1-2014 Critical Animal Studies: An Introduction by Dawne McCance Rosemary-Claire Collard University of Toronto Part of the Ethics and Political Philosophy Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Follow this and additional works at / Suivez-nous ainsi que d’autres travaux et œuvres: https://scholars.wlu.ca/thegoose Recommended Citation / Citation recommandée Collard, Rosemary-Claire. "Critical Animal Studies: An Introduction by Dawne McCance." The Goose, vol. 13 , no. 1 , article 25, 2014, https://scholars.wlu.ca/thegoose/vol13/iss1/25. This article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Goose by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cet article vous est accessible gratuitement et en libre accès grâce à Scholars Commons @ Laurier. Le texte a été approuvé pour faire partie intégrante de la revue The Goose par un rédacteur autorisé de Scholars Commons @ Laurier. Pour de plus amples informations, contactez [email protected]. Collard: Critical Animal Studies: An Introduction by Dawne McCance Made, not born, machines this reduction is accomplished and what its implications are for animal life and Critical Animal Studies: An Introduction death. by DAWNE McCANCE After a short introduction in State U of New York P, 2013 $22.65 which McCance outlines the hierarchical Cartesian dualism (mind/body, Reviewed by ROSEMARY-CLAIRE human/animal) to which her book and COLLARD critical animal studies’ are opposed, McCance turns to what are, for CAS The field of critical animal scholars, familiar figures in a familiar studies (CAS) is thoroughly multi- place: Peter Singer and Tom Regan on disciplinary and, as Dawne McCance’s the factory farm. -

An Inquiry Into Animal Rights Vegan Activists' Perception and Practice of Persuasion

An Inquiry into Animal Rights Vegan Activists’ Perception and Practice of Persuasion by Angela Gunther B.A., Simon Fraser University, 2006 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the School of Communication ! Angela Gunther 2012 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2012 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for “Fair Dealing.” Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. Approval Name: Angela Gunther Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: An Inquiry into Animal Rights Vegan Activists’ Perception and Practice of Persuasion Examining Committee: Chair: Kathi Cross Gary McCarron Senior Supervisor Associate Professor Robert Anderson Supervisor Professor Michael Kenny External Examiner Professor, Anthropology SFU Date Defended/Approved: June 28, 2012 ii Partial Copyright Licence iii Abstract This thesis interrogates the persuasive practices of Animal Rights Vegan Activists (ARVAs) in order to determine why and how ARVAs fail to convince people to become and stay veg*n, and what they might do to succeed. While ARVAs and ARVAism are the focus of this inquiry, the approaches, concepts and theories used are broadly applicable and therefore this investigation is potentially useful for any activist or group of activists wishing to interrogate and improve their persuasive practices. Keywords: Persuasion; Communication for Social Change; Animal Rights; Veg*nism; Activism iv Table of Contents Approval ............................................................................................................................. ii! Partial Copyright Licence ................................................................................................. -

SASH68 Critical Animal Studies: Animals in Society, Culture and the Media

SASH68 Critical Animal Studies: Animals in society, culture and the media List of readings Approved by the board of the Department of Communication and Media 2019-12-03 Introduction to the critical study of human-animal relations Adams, Carol J. (2009). Post-Meateating. In T. Tyler and M. Rossini (Eds.), Animal Encounters Leiden and Boston: Brill. pp. 47-72. Emel, Jody & Wolch, Jennifer (1998). Witnessing the Animal Moment. In J. Wolch & J. Emel (Eds.), Animal Geographies: Place, Politics, and Identity in the Nature- Culture Borderlands. London & New York: Verso pp. 1-24 LeGuin, Ursula K. (1988). ’She Unnames them’, In Ursula K. LeGuin Buffalo Gals and Other Animal Presences. New York, N.Y.: New American Library. pp. 1-3 Nocella II, Anthony J., Sorenson, John, Socha, Kim & Matsuoka, Atsuko (2014). The Emergence of Critical Animal Studies: The Rise of Intersectional Animal Liberation. In A.J. Nocella II, J. Sorenson, K. Socha & A. Matsuoka (Eds.), Defining Critical Animal Studies: An Intersectional Social Justice Approach for Liberation. New York: Peter Lang. pp. xix-xxxvi Salt, Henry S. (1914). Logic of the Larder. In H.S. Salt, The Humanities of Diet. Manchester: Sociey. 3 pp. Sanbonmatsu, John (2011). Introduction. In J. Sanbonmatsu (Ed.), Critical Theory and Animal Liberation. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 1-12 + 20-26 Stanescu, Vasile & Twine, Richard (2012). ‘Post-Animal Studies: The Future(s) of Critical Animal Studies’, Journal of Critical Animal Studies 10(2), pp. 4-19. Taylor, Sunara. (2014). ‘Animal Crips’, Journal for Critical Animal Studies. 12(2), pp. 95-117. /127 pages Social constructions, positions, and representations of animals Arluke, Arnold & Sanders, Clinton R. -

Centre for the Study of Social and Political

CENTRE FOR THE STUDY ABOUT OF SOCIAL AND The Centre for the Study of Social and Political Movements was established in 1992, and since then has helped the University of Kent gain wider POLITICAL recognition as a leading institution in the study of social and political movements in the UK. The Centre has attracted research council, European Union, and charitable foundation funding, and MOVEMENTS collaborated with international partners on major funding projects. Former staff members and external associates include Professors Mario Diani, Frank Furedi, Dieter Rucht, and Clare Saunders. Spri ng 202 1 Today, the Centre continues to attract graduate students and international visitors, and facilitate the development of collaborative research. Dear colleagues, Recent and ongoing research undertaken by members includes studies of Black Lives Matter, Extinction Rebellion, veganism and animal rights. Things have been a bit quiet in the center this year as we’ve been teaching online and unable to meet in person. That said, social The Centre takes a methodologically pluralistic movements have not been phased by the pandemic. In the US, Black and interdisciplinary approach, embracing any Lives Matter protests trudge on, fueled by the recent conviction of topic relevant to the study of social and political th movements. If you have any inquiries about George Floyd’s murder on April 20 and the police killing of 16 year old Centre events or activities, or are interested in Ma'Khia Bryant in Ohio that same day. Meanwhile, the killing of Kent applying for our PhD programme, please contact resident Sarah Everard (also by a police officer) spurred considerable Dr Alexander Hensby or Dr Corey Wrenn. -

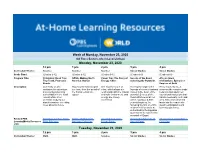

WORLD CHANNEL At-Home Learning Block Fall 2020

Week of Monday, November 23, 2020 (All Times Eastern, Check Local Listings) Monday, November 23, 2020 12 pm 1 pm 2 pm 3 pm 4 pm Curriculum/Theme: Science Science Science Social Studies Social Studies Grade Band: (Grades 6-12) (Grades 6-12) (Grades 9-12 (Grades 6-9) (Grades 6-9) Program Title: Prehistoric Road Trip: NOVA: Making North Power Trip: The Story of Secrets of the Dead: Africa's Great Tiny Teeth, Fearsome America: Human Energy: Cities Scanning the Pyramids Civilizations, Episode 3: Beasts Empires of Gold Description: Join Emily as she How has the land shaped See how the future of Tracing the origin of the Henry Louis Gates, Jr. continues her adventure, our lives, from the arrival of cities, which shape our legends of secret chambers uncovers the complex trade discovering surprising the first Americans to relationship with the natural hidden in the heart of the networks and advanced truths hidden in the fossil today? and built environment, and pyramid, Secrets of the educational institutions that record, while other energy are closely Dead will show what lies transformed early north and scientists studying our connected. within, solving a 4,500- west Africa from deserted planet's past are revealing year-old mystery, by lands into the continent’s clues about its future. following the first scientific wealthiest kingdoms and mission in 30 years to be learning epicentres. authorized by the Egyptian government to examine the pyramids of Egypt Related PBS Antartica's Ice-Free Past | NOVA: Making North Deciding Your City's Building -

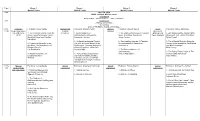

2010 Schedule Chart (8 1/2 X 14 In

Time Room 1. Room 2. Room 3. Room 4. Moffett Center Moffett Center Moffett Center Moffett Center 9:00 April 10, 2010 SUNY Cortland, Moffett Center Registration Sarat Colling - Elizabeth Green – Ashley Mosgrove 9:30 Introduction Anthony J. Nocella, II Welcoming Andrew Fitz-Gibbon and Mechthild Nagel 10:00 – Academic Facilitator: Jackie Riehle Animals and Facilitator: Ronald Pleban Species Facilitator: Doreen Nieves Social Facilitator: Ashley Mosgrove 11:20 Repression Book Cultural Inclusion Movement Talk (AK Press, 1. The Carceral Society: From the Practices 1 Animal Subjects in 1. The Politics of Inclusion: A Feminist Strategy and 1. DIY Media and the Animal Rights 2010) Prison Tower to the Ivory Tower Anthropological Perspective Space to Critique Speciesism Tactic Analysis Movement: Talk - Action = Nothing Mechthild Nagel and Caroline Alessandro Arrigoni Jenny Grubbs Dylan Powell Kaltefleiter 2. An American Imperial Project: 2. Transcending Species: A Feminist 2. The Influential Activist: Using the 2. Regimes of Normalcy in the The Role of Animal Bodies in the Re-examination of Oppression Science of Persuasion to Open Minds Academy: The Experiences of Smithsonian-Theodore Roosevelt Jeni Haines and Win Campaigns Disabled Faculty African Expedition, 1909-1910. Nick Cooney Liat Ben-Moshe Laura Shields 3. The Reasonableness of Sentimentality 3. The Role of Direct Action in The 3. Adelphi Recovers „The 3. Conservation perspectives: Andrew Fitz-Gibbon Animal Rights Movement Lengthening View International wildlife priorities, Carol Glasser Ali Zaidi individual animals, and wildlife management strategies in Kenya Stella Capoccia 11:30- Species Facilitator: Jackie Riehle Animal Facilitator: Anastasia Yarbrough Animal Facilitator: Brittani Mannix Animal Facilitator: Andrew Fitz-Gibbon 1:00 Relationships Exploitation Exploitation Exploitation and Domination 1. -

Hacking Your Mind September 9, 9:30Pm Primetime

September 2020 September 2020 PRIMETIME PRIMETIME Hacking Your Mind September 9, 9:30pm primetime 1 TUESDAY 8:00 OPB Suze Orman’s Ultimate Retirement Guide The personal finance 7:00 OPB PBS NewsHour | OPB+ Greatest expert provides essential advice on planning Bond Inmates, veterans and service dogs for retirement. (Also Sat 3:30pm) | OPB+ unite in a story of redemption and hope. (Also Himalaya Connection See how the Wed 5am) Himalaya’s tectonic plates impact the region. 8:00 OPB Frontline From Jesus to Christ: The (Also Sat 12am) First Christians, Pts 1&2. Historical evidence 9:00 OPB+ Prehistoric Road Trip Tiny Teeth, illuminates the origins of Christianity. (Also Fri Fearsome Beasts (Also Sat 1am) 12am) | OPB+ Spy in the Wild: A Nature Miniseries The Tropics. Animatronic ‘spy 10:00 OPB Henry Louis Gates, Jr.: cameras’ record animal behavior in the wild. Uncovering America Get to know the renowned historian, author and filmmaker. (Also Thu 12am) BBC (Also Sat 2pm) | OPB+ Amanpour & 9:00 OPB+ Big Pacific Mysterious. Dive Company (Also Fri 4am) into the Pacific to see the ocean’s rare and Sam Smith: dazzling creatures. (Also Thu 1am) 11: 00 OPB+ DW Global 3000 (Also Sat 2am) Live at the BBC’s 10:00 OPB+ Amanpour & Company (Also 11:30 OPB+ Articulate With Jim Cotter Wed 4am) Halloween (Also Sat 2:30am) Biggest Weekend Experience the thrill of Grammy 11: 00 OPB Rick Steves Holy Land: Israelis and Palestinians Today Rick visits sites 4 FRIDAY Award-winner Sam Smith’s and explores Israeli and Palestinian narratives electrifying summer concert. -

I Am a Dinosaur #Iamadinosaur

ACTIVE SCHOOL SERIES Please follow the ‘Assembly Intructions’ when using Kitcamp. DATE: 2017-11 #I AM A DINOSAUR #IAMADINOSAUR OVERVIEW WORKS WITH: GROUP SIZE: Get them moving! Set up the kitcamp equipment as a nest EYFS INDIVIDUAL for the dinosaur’s eggs, a volcano, a swamp, a lost island, or a cave or lair to create a backdrop to a myriad of games and ways KS1 SMALL of moving. Creating a scene for the ‘dinosaurs’ will encourage KS2 LARGE running, jumping, throwing, balancing, sliding and hopping; they’ll be practising their dinosaur moves, playing story-games SEN (endorsed) and getting active before you know it. The kit can be a base or a den, or a dinosaur with a jaggardy tail. EYFS and National Curriculum targets applicable. INSPIRATION EXPLORATION ADDITIONAL RESOURCES Stories: Dinosaurs come in all shapes and sizes, some fly, some stomp, some are giants, Kitcamp Accessories: cutout panels, Mad About Dinosaurs, by Giles Andreae others tiny. Captivate the imagination with dinosaur songs and clips, look at how cardboard inserts, basin (nest), plugs, blue Stomp, Dinosaur, Stomp, by Margaret Mayo dinosaurs’ bodies move . Add ‘dinosaur actions’ to rhymes and stories as the canopy (water), green canopy (swamp). Dinosaurumptus, Tony Mitton catalyst for prehistoric games and dinosaur moves. Mats (roll mats or gym mats) to mark What if a dinosaur? There’s a T Rex in Town, Ruth Symons Leave picture books open for children to mimic each dinosaur’s moves (perhaps out zones. ‘Stomp, Chomp, Big Roars! Here come the Dinosaurs!’ by in front of a mirror). Add in percussion instruments or music that encourages Materials: cargo net, small world dinosaurs. -

A Night at Off Every Purchase in the Store

Summer 2015 MUSEUM STORE Find unique gifts for every occasion! Members receive 10% a night at off every purchase in the store. iverfront Handmade jewelry Art & science kits R Locally made gifts Games & puzzles Museum Books for all ages Art & greeting cards + + Plushies & toys Eco-friendly gifts SO MUCH TO DISCOVER AT THE RIVERFRONT MUSEUM adults like sleepovers too! “There’s such a unique and great store at the Museum. I love Find out more: shopping for my kids there because you have things no one RiverfrontMuseum.org Sat, Jul 25 else has.” JF DINOSAURS IN MOTION In this unique, new exhibition, dinosaurs are the medium for educating and exciting multi-generational families on STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts & Mathematics) concepts. Dinosaurs in Motion educates the visitor by using 14 magnificent, A person who never made a mistake, fully interactive, recycled metal dinosaur never tried anything new. sculptures with exposed mechanics inspired - Albert Einstein by actual fossils. Look for more information on page 4! PRESENTED BY Nothing in life is to be feared. It is only to be understood. - Marie Curie CONTENTS 4TH OF JULY BACKYARD BBQ 2 GIANT SCREEN THEATER 2 MEMBERSHIP 3 PARTY ON THE PLAZA 3 DINOSAURS IN MOTION 4 UPCOMING EXHIBITS 5 Peoria, IL 61602 IL Peoria, PLANETARIUM 6 222 SW Washington Street Washington SW 222 Permit No. 858 No. Permit MUSEUM SCHOOL 7 Peoria, Illinois Peoria, Peoria Riverfront Museum Riverfront Peoria PAID SUMMER CAMP 7 US Postage US Non-Profit NIGHT AT THE RIVERFRONT MUSEUM 8 Find out more: RiverfrontMuseum.org This program is partially supported by a grant from the Illinois Arts Council Agency.