CRITICAL TERMS for ANIMAL STUDIES

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Course Syllabus Animal Studies: an Introduction ANTH S-1625 Harvard Summer School 2016 Dr

2016.6.10 draft Course Syllabus Animal Studies: An Introduction ANTH S-1625 Harvard Summer School 2016 Dr. Paul Waldau Course Description This course traces the history and shape of academic efforts to study nonhuman animals. Animal studies scholars explore such questions as, how do contemporary Western societies characterize the differences between humans and non-human animals? What ethical debates surround the use of animals in scientific research or the use of animals for food? How different are other cultures’ views of nonhuman animals from the views that now prevail in the United States and other early twenty-first century industrialized societies? What assumptions in educational systems have fostered the study of nonhuman animals, and what assumptions of specific educational systems have hampered such study? Class sessions are discussion-based, and students undertake group work, significant writing, and an individual presentation. In addition, note carefully each of the Learning Objectives listed below. We will discuss these objectives regularly through significant writing, group-based discussion and individual presentations that explore the interdisciplinary implications of weaving together the humanities with sciences (both social and natural). There are no prerequisites for this course. Required Readings and Course Materials • Waldau, Paul 2013. Animal Studies: An Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press • Additional Course Materials will be specified, and most of them will be available online or in .pdf format at the -

The Anniversary Book

THE ANNIVERSARY BOOK 50 YEARS OF LEADERSHIP: CONTINUING THE VISION CELEBRATING 50 YEARS OF THE COMMUNICATING NURSING RESEARCH CONFERENCE and 60TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE WESTERN COUNCIL ON HIGHER EDUCATION FOR NURSING (WCHEN) / THE WESTERN INSTITUTE OF NURSING (WIN) The Western Institute of Nursing is indebted to Elaine S. Marshall, PhD, RN, FAAN, who, with colleagues, created the 50th Communicating Nursing Research Conference anniversary book. The history of this trailblazing conference cannot be told without the story of the 60th anniversary of the Western Council on Higher Education for Nursing (WCHEN) / Western Institute of Nursing (WIN), which originated and continues to offer this landmark conference. WCHEN/WIN was founded on this principle: nursing research, education and the improvement of patient care highly interrelated. This principle endures today and into the future. Finally, the Anniversary Book tells the story of the strong leaders who originated the organization and conference. We stand on the shoulders of these Western giants. WESTERN INSTITUTE OF NURSING SN-4S 3455 SW US VETERANS HOSPITAL ROAD PORTLAND, OR 97239-2941 An Affirmative Action/Equal Opportunity Employer Spring 2017 table OF CONTENTS preface . 5 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS . 7 CHAPTER ONE . 9 THE WORK BEGINS: 1951-1968 CHAPTER TWO . 33 LAUNCHING COMMUNICATING NURSING RESEARCH, 1968-1973 CHAPTER THREE . 53 Communicating Nursing Research, 1974-1985: “Experimentation AND CHANGE” AND “CHANGING OF THE GUARD” CHAPTER FOUR . 77 Communicating Nursing Research, 1986-1999: “BROADENED HORIZONS,” “SILVER THREADS,” AND THE SCIENCE GROWS CHAPTER FIVE . 97 Communicating Nursing Research, 2000-2017: National AND International LEGACY AND INFLUENCE CHAPTER SIX . 123 Communicating Nursing Research: 50 YEARS AND BEYOND 60-YEAR TIMELINE OF THE WESTERN INSTITUTE OF NURSING (WIN) . -

What's the Difference Between the B.A. and B.S. Degree In

What’s the Difference Between the B.A. and B.S. Degree in ES? 8.1.20 If you’re thinking about pursuing Environmental Studies (ES) at UC Santa Barbara the first important decision you have to make is choosing which degree to pursue, the Bachelor of Arts (B.A.) or Bachelor of Science (B.S.) in Environmental Studies. While both majors are similar in design and stress the importance of understanding the complex interrelationships between the humanities, social sciences, and natural science disciplines, having two degree options allows students maximum flexibility to choose a major that best fits their environmental interests and goals. In this document we provide a detailed comparison of the academic requirements of the B.A. and B.S. major so one can understand the differences and can make an educated decision. Given your decision will also be based on what you want to do after graduation we thought it might be helpful to also highlight just a few example career paths each degree might lead to. Just remember, no matter which major you choose, your decision should be based on what you believe will ultimately make you happy. Simply put, the B.A. degree in ES is the more interdisciplinary major, requiring a swath of introductory courses in the humanities, social, physical, and natural sciences. It stresses the importance of comprehending basic social, cultural, and scientific theories and understanding how they interact with one another and play an important part of every environmental issue. While this degree will make one science literate, the degree offers maximum flexibility to select ES electives and outside concentration courses from just about every academic discipline at UCSB, including: arts, policy, culture, languages, humanities, and economics to name just a few. -

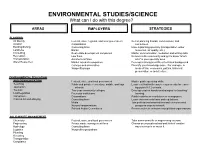

ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES/SCIENCE What Can I Do with This Degree?

ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES/SCIENCE What can I do with this degree? AREAS EMPLOYERS STRATEGIES PLANNING Air Quality Federal, state, regional, and local government Get on planning boards, commissions, and Aviation Corporations committees. Building/Zoning Consulting firms Have a planning specialty (transportation, water Land-Use Banks resources, air quality, etc.). Consulting Real estate development companies Master communication, mediation and writing skills. Recreation Law firms Network in the community and get to know "who's Transportation Architectural firms who" in your specialty area. Water Resources Market research companies Develop a strong scientific or technical background. Colleges and universities Diversify your knowledge base. For example, in Nonprofit groups areas of law, economics, politics, historical preservation, or architecture. ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION AND COMMUNICATION Federal, state, and local government Master public speaking skills. Teaching Public and private elementary, middle, and high Learn certification/licensure requirements for teach- Journalism schools ing public K-12 schools. Tourism Two-year community colleges Develop creative hands-on strategies for teaching/ Law Regulation Four-year institutions learning. Compliance Corporations Publish articles in newsletters or newspapers. Political Action/Lobbying Consulting firms Learn environmental laws and regulations. Media Join professional associations and environmental Nonprofit organizations groups as ways to network. Political Action Committees Become active in environmental -

Giving Voice to the "Voiceless:" Incorporating Nonhuman Animal Perspectives As Journalistic Sources

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Communication Faculty Publications Department of Communication 2011 Giving Voice to the "Voiceless:" Incorporating Nonhuman Animal Perspectives as Journalistic Sources Carrie Packwood Freeman Georgia State University, [email protected] Marc Bekoff Sarah M. Bexell [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_facpub Part of the Journalism Studies Commons, and the Social Influence and oliticalP Communication Commons Recommended Citation Freeman, C. P., Bekoff, M. & Bexell, S. (2011). Giving voice to the voiceless: Incorporating nonhuman animal perspectives as journalistic sources. Journalism Studies, 12(5), 590-607. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Communication at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VOICE TO THE VOICELESS 1 A similar version of this paper was later published as: Freeman, C. P., Bekoff, M. & Bexell, S. (2011). Giving Voice to the Voiceless: Incorporating Nonhuman Animal Perspectives as Journalistic Sources, Journalism Studies, 12(5), 590-607. GIVING VOICE TO THE "VOICELESS": Incorporating nonhuman animal perspectives as journalistic sources Carrie Packwood Freeman, Marc Bekoff and Sarah M. Bexell As part of journalism’s commitment to truth and justice -

Ways of Seeing Animals Documenting and Imag(In)Ing the Other in the Digital Turn

InMedia The French Journal of Media Studies 8.1. | 2020 Ubiquitous Visuality Ways of Seeing Animals Documenting and Imag(in)ing the Other in the Digital Turn Diane Leblond Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/inmedia/1957 DOI: 10.4000/inmedia.1957 ISSN: 2259-4728 Publisher Center for Research on the English-Speaking World (CREW) Electronic reference Diane Leblond, “Ways of Seeing Animals”, InMedia [Online], 8.1. | 2020, Online since 15 December 2020, connection on 26 January 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/inmedia/1957 ; DOI: https:// doi.org/10.4000/inmedia.1957 This text was automatically generated on 26 January 2021. © InMedia Ways of Seeing Animals 1 Ways of Seeing Animals Documenting and Imag(in)ing the Other in the Digital Turn Diane Leblond Introduction. Looking at animals: when visual nature questions visual culture 1 A topos of Western philosophy indexes animals’ irreducible alienation from the human condition on their lack of speech. In ancient times, their inarticulate cries provided the necessary analogy to designate non-Greeks as other, the adjective “Barbarian” assimilating foreign languages to incomprehensible birdcalls.1 To this day, the exclusion of animals from the sphere of logos remains one of the crucial questions addressed by philosophy and linguistics.2 In the work of some contemporary critics, however, the tenets of this relation to the animal “other” seem to have undergone a change in focus. With renewed insistence that difference is inextricably bound up in a sense of proximity, such writings have described animals not simply as “other,” but as our speechless others. This approach seems to find particularly fruitful ground where theory proposes to explore ways of seeing as constitutive of the discursive structures that we inhabit. -

Animals and the Frontiers of Citizenship

Oxford Journal of Legal Studies, Vol. 34, No. 2 (2014), pp. 201–219 doi:10.1093/ojls/gqu001 Published Advance Access February 5, 2014 Animals and the Frontiers of Citizenship Will Kymlicka* and Sue Donaldson** Abstract —Citizenship has been at the core of struggles by historically excluded Downloaded from groups for respect and inclusion. Can citizenship be extended even further to domesticated animals? We begin this article by sketching an argument for why justice requires the extension of citizenship to domesticated animals, above and beyond compassionate care, stewardship or universal basic rights. We then consider two objections to this argument. Some animal rights theorists worry that extending citizenship to domesticated animals, while it may sound progressive, would in fact http://ojls.oxfordjournals.org/ be bad for animals, providing yet another basis for policing their behaviour to fit human needs and interests. Critics of animal rights, on the other hand, worry that the inclusion of ‘unruly’ beasts would be bad for democracy, eroding its core values and principles. We attempt to show that both objections are misplaced, and that animal citizenship would both promote justice for animals and deepen fundamental democratic dispositions and values. Keywords: citizenship, animal rights, justice, co-operation at Queen's University on June 23, 2014 1. Introduction In our recent book Zoopolis, we made the case for a distinctly ‘political theory of animal rights’.1 In this Lecture, we attempt to extend that argument, and to respond to some critics of it, by focusing specifically on the novel idea of ‘animal citizenship’. To begin, let us briefly situate our approach in the larger animal rights debate. -

Lands of the Lakota: Policy, Culture and Land Use on the Pine Ridge

1 Lands of the Lakota: Policy, Culture and Land Use on the Pine Ridge Reservation Joseph Stromberg Senior Honors Thesis Environmental Studies and Anthropology Washington University in St. Louis 2 Abstract Land is invested with tremendous historical and cultural significance for the Oglala Lakota Nation of the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. Widespread alienation from direct land use among tribal members also makes land a key element in exploring the roots of present-day problems—over two thirds of the reservation’s agricultural income goes to non-Natives, while the majority of households live below the poverty line. In order to understand how current patterns in land use are linked with federal policy and tribal culture, this study draws on three sources: (1) archival research on tribal history, especially in terms of territory loss, political transformation, ethnic division, economic coercion, and land use; (2) an account of contemporary problems on the reservation, with an analysis of current land policy and use pattern; and (3) primary qualitative ethnographic research conducted on the reservation with tribal members. Findings indicate that federal land policies act to effectively block direct land use. Tribal members have responded to policy in ways relative to the expression of cultural values, and the intent of policy has been undermined by a failure to fully understand the cultural context of the reservation. The discussion interprets land use through the themes of policy obstacles, forced incorporation into the world-system, and resistance via cultural sovereignty over land use decisions. Acknowledgements I would like to sincerely thank the Buder Center for American Indian Studies of the George Warren Brown School of Social Work as well as the Environmental Studies Program, for support in conducting research. -

All Creation Groans: the Lives of Factory Farm Animals in the United States

InSight: RIVIER ACADEMIC JOURNAL, VOLUME 13, NUMBER 1, SPRING 2017 “ALL CREATION GROANS”: The Lives of Factory Farm Animals in the United States Sr. Lucille C. Thibodeau, pm, Ph.D.* Writer-in-Residence, Department of English, Rivier University Today, more animals suffer at human hands than at any other time in history. It is therefore not surprising that an intense and controversial debate is taking place over the status of the 60+ billion animals raised and slaughtered for food worldwide every year. To keep up with the high demand for meat, industrialized nations employ modern processes generally referred to as “factory farming.” This article focuses on factory farming in the United States because the United States inaugurated this approach to farming, because factory farming is more highly sophisticated here than elsewhere, and because the government agency overseeing it, the Department of Agriculture (USDA), publishes abundant readily available statistics that reveal the astonishing scale of factory farming in this country.1 The debate over factory farming is often “complicated and contentious,”2 with the deepest point of contention arising over the nature, degree, and duration of suffering food animals undergo. “In their numbers and in the duration and depth of the cruelty inflicted upon them,” writes Allan Kornberg, M.D., former Executive Director of Farm Sanctuary in a 2012 Farm Sanctuary brochure, “factory-farm animals are the most widely abused and most suffering of all creatures on our planet.” Raising the specter of animal suffering inevitably raises the question of animal consciousness and sentience. Jeremy Bentham, the 18th-century founder of utilitarianism, focused on sentience as the source of animals’ entitlement to equal consideration of interests. -

Rolston on Animals, Ethics, and the Factory Farm

[Expositions 6.1 (2012) 29–40] Expositions (online) ISSN: 1747–5376 Unnaturally Cruel: Rolston on Animals, Ethics, and the Factory Farm CHRISTIAN DIEHM University of Wisconsin, Stevens Point In 2010, over nine billion animals were killed in the United States for human consumption. This included nearly 1 million calves, 2.5 million sheep and lambs, 34 million cattle, 110 million hogs, 242 million turkeys, and well over 8.7 billion chickens (USDA 2011a; 2011b). Though hundreds of slaughterhouses actively contributed to these totals, more than half of the cattle just mentioned were killed at just fourteen plants. A slightly greater percentage of hogs was killed at only twelve (USDA 2011a). Chickens were processed in a total of three hundred and ten federally inspected facilities (USDA 2011b), which means that if every facility operated at the same capacity, each would have slaughtered over fifty-three birds per minute (nearly one per second) in every minute of every day, adding up to more than twenty-eight million apiece over the course of twelve months.1 Incredible as these figures may seem, 2010 was an average year for agricultural animals. Indeed, for nearly a decade now the total number of birds and mammals killed annually in the US has come in at or above the nine billion mark, and such enormous totals are possible only by virtue of the existence of an equally enormous network of industrialized agricultural suppliers. These high-volume farming operations – dubbed “factory farms” by the general public, or “Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs)” by state and federal agencies – are defined by the ways in which they restrict animals’ movements and behaviors, locate more and more bodies in less and less space, and increasingly mechanize many aspects of traditional husbandry. -

Critical Animal Studies: an Introduction by Dawne Mccance Rosemary-Claire Collard University of Toronto

The Goose Volume 13 | No. 1 Article 25 8-1-2014 Critical Animal Studies: An Introduction by Dawne McCance Rosemary-Claire Collard University of Toronto Part of the Ethics and Political Philosophy Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Follow this and additional works at / Suivez-nous ainsi que d’autres travaux et œuvres: https://scholars.wlu.ca/thegoose Recommended Citation / Citation recommandée Collard, Rosemary-Claire. "Critical Animal Studies: An Introduction by Dawne McCance." The Goose, vol. 13 , no. 1 , article 25, 2014, https://scholars.wlu.ca/thegoose/vol13/iss1/25. This article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Goose by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cet article vous est accessible gratuitement et en libre accès grâce à Scholars Commons @ Laurier. Le texte a été approuvé pour faire partie intégrante de la revue The Goose par un rédacteur autorisé de Scholars Commons @ Laurier. Pour de plus amples informations, contactez [email protected]. Collard: Critical Animal Studies: An Introduction by Dawne McCance Made, not born, machines this reduction is accomplished and what its implications are for animal life and Critical Animal Studies: An Introduction death. by DAWNE McCANCE After a short introduction in State U of New York P, 2013 $22.65 which McCance outlines the hierarchical Cartesian dualism (mind/body, Reviewed by ROSEMARY-CLAIRE human/animal) to which her book and COLLARD critical animal studies’ are opposed, McCance turns to what are, for CAS The field of critical animal scholars, familiar figures in a familiar studies (CAS) is thoroughly multi- place: Peter Singer and Tom Regan on disciplinary and, as Dawne McCance’s the factory farm. -

4Th MINDING ANIMALS CONFERENCE CIUDAD DE

th 4 MINDING ANIMALS CONFERENCE CIUDAD DE MÉXICO, 17 TO 24 JANUARY, 2018 SOCIAL PROGRAMME: ROYAL PEDREGAL HOTEL ACADEMIC PROGRAMME: NATIONAL AUTONOMOUS UNIVERSITY OF MEXICO Auditorio Alfonso Caso and Anexos de la Facultad de Derecho FINAL PROGRAMME (Online version linked to abstracts. Download PDF here) 1/47 All delegates please note: 1. Presentation slots may have needed to be moved by the organisers, and may appear in a different place from that of the final printed programme. Please consult the schedule located in the Conference Programme upon arrival at the Conference for your presentation time. 2. Please note that presenters have to ensure the following times for presentation to allow for adequate time for questions from the floor and smooth transition of sessions. Delegates must not stray from their allocated 20 minutes. Further, delegates are welcome to move within sessions, therefore presenters MUST limit their talk to the allocated time. Therefore, Q&A will be AFTER each talk, and NOT at the end of the three presentations. Plenary and Invited Talks – 45 min. presentation and 15 min. discussion (Q&A). 3. For panels, each panellist must stick strictly to a 10 minute time frame, before discussion with the floor commences. 4. Note that co-authors may be presenting at the conference in place of, or with the main author. For all co-authors, delegates are advised to consult the Conference Abstracts link on the Minding Animals website. Use of the term et al is provided where there is more than two authors of an abstract. 5. Moderator notes will be available at all front desks in tutorial rooms, along with Time Sheets (5, 3 and 1 minute Left).