Methods of Coaching to Improve Decision Making in Rugby

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Position-Specific Rugby Skills Handbook About This Handbook

POSITION-SPECIFIC RUGBY SKILLS HANDBOOK ABOUT THIS HANDBOOK Thank you for downloading the Ruck Science position-specifc rugby skills handbook. This handbook is designed for amateur rugby players, coaches and parents as a guide to creating tailored training programs that meet the needs of each individual position on a rugby team. The handbook will take readers through the specifc physical and technical demands of each position as well as the training associated with building the requisite skill set. We would like to use this opportunity to thank several organizations without whom this handbook would not have been possible. Firstly, the Canadian Rugby Union who created a similar guide in 2009. This version has drawn a lot of inspiration from that original work which was itself a derivative of a manual set up by the English Rugby Union. Secondly, the writing team of Tudor Bompa & Frederick Claro whose trans-formative work Periodization in Rugby was also published in 2009. “Periodization in Rugby” is, without a doubt, the most complete analysis of periodized training for amateur rugby players and should be essential reading for all rugby coaches who are working with young players. Sincerely, Tim Howard Founder Ruck Science TABLE OF CONTENTS 2. About this handbook 4. Physical preparation for rugby 5. Warming up 5. Cooling down 6. Key rugby skills 6. Healthy eating 7. Prop 15. Hooker 21. Lock 27. Flanker 36. Number 8 42. Scrumhalf 47. Flyhalf 52. Center 56. Wing 61. Fullback Riekert Hattingh SEATTLE SEAWOLVES RUGBY SHORTS WITH POCKETS The world’s most comfortable rugby shorts, with deep, strong pockets on both sides. -

RUGBY GENERAL DESCRIPTION of the GAME Rugby Is Played at a Fast Pace, with Few Stoppages and Continuous Possession Changes

RUGBY GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF THE GAME Rugby is played at a fast pace, with few stoppages and continuous possession changes. All players on the field, regardless of position, must be able to run, pass, kick and catch the ball. Likewise, all players must also be able to tackle and defend, making each position both offensive and defensive in nature. There is no blocking of the opponents like in football. A rugby match consists of two 40-minute halves. FIELD OF PLAY Rugby is played on a field, called a pitch, that is longer and wider than a football field, more like a soccer field. A typical pitch is 100 meters (110 yards) long 70 meters (75 yards) wide. Additionally, there are 10-22 meter end zones, called the in-goal area, behind the goalposts. The goalposts are 'H'-shaped cross bars located on the goal line and are the same size as American football goalposts. THE BALL The rugby ball is made of leather or other similar synthetic material that is easy to grip and does not have laces. Rugby balls are made in varying sizes (3, 4 or 5) for both youth and adult players. Like footballs, rugby balls are oval in shape, however are rounder and less pointed than footballs to minimize the erratic bounces we see in football. PLAYERS & POSITIONS A rugby team has 15 players on the field of play, both American football and soccer have 11 players on each team. In rugby, each team is numbered the exact same way. The number of each player signifies that player's position. -

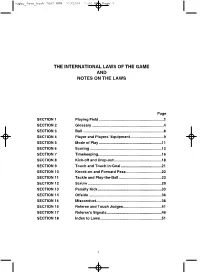

The International Laws of the Game and Notes on the Laws

rugby_laws_book 2002 NEW 11/3/04 1:00 PM Page 1 THE INTERNATIONAL LAWS OF THE GAME AND NOTES ON THE LAWS Page SECTION 1 Playing Field ..............................................................2 SECTION 2 Glossary .....................................................................4 SECTION 3 Ball ..............................................................................8 SECTION 4 Player and Players’ Equipment ................................9 SECTION 5 Mode of Play ............................................................11 SECTION 6 Scoring .....................................................................12 SECTION 7 Timekeeping.............................................................16 SECTION 8 Kick-off and Drop-out..............................................18 SECTION 9 Touch and Touch in-Goal .......................................21 SECTION 10 Knock-on and Forward Pass ..................................22 SECTION 11 Tackle and Play-the-Ball .........................................23 SECTION 12 Scrum .......................................................................29 SECTION 13 Penalty Kick .............................................................33 SECTION 14 Offside ......................................................................36 SECTION 15 Misconduct...............................................................38 SECTION 16 Referee and Touch Judges.....................................41 SECTION 17 Referee’s Signals.....................................................46 SECTION 18 Index -

Attacking 22 Entries in Rugby Union: Running Demands and Differences Between Successful and Unsuccessful Entries

Accepted: 14 November 2016 DOI: 10.1111/sms.12816 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Attacking 22 entries in rugby union: running demands and differences between successful and unsuccessful entries P. Tierney1,2 | D. P. Tobin1 | C. Blake2 | E. Delahunt1,3 1Leinster Rugby, Dublin, Ireland Global Positioning System (GPS) technology is commonly utilized in team sports, 2School of Public Health, Physiotherapy and Sports Science, University College Dublin, including rugby union. It has been used to describe the average running demands of Dublin, Ireland rugby union. This has afforded an enhanced understanding of the physical fitness 3Institute for Sport and Health, University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland requirements for players. However, research in team sports has suggested that train- ing players relative to average demands may underprepare them for certain scenarios Correspondence Peter Tierney, Leinster Rugby, Dublin, Ireland. within the game. To date, no research has investigated the running demands of at- Email: [email protected] tacking 22 entries in rugby union. Additionally, no research has been undertaken to determine whether differences exist in the running intensity of successful and unsuc- cessful attacking 22 entries in rugby union. The first aim of this study was to describe the running intensity of attacking 22 entries. The second aim of this study was to investigate whether differences exist in the running intensity of successful and un- successful attacking 22 entries. Running intensity was measured using meters per minute (m min−1) for (a) total distance, (b) running distance, (c) high- speed running distance, and (d) very high- speed running distance. This study provides normative data for the running intensity of attacking 22 entries in rugby union. -

Flex Football Rule Book – ½ Field

Flex Football Rule Book – ½ Field This rule book outlines the playing rules for Flex Football, a limited-contact 9-on-9 football game that incorporates soft-shelled helmets and shoulder pads. For any rules not specifically addressed below, refer to either the NFHS rule book or the NCAA rule book based on what serves as the official high school-level rule book in your state. Flex 1/2 Field Setup ● The standard football field is divided in half with the direction of play going from the mid field out towards the end zone. ● 2 Flex Football games are to be run at the same going in opposing directions towards the end zones on their respective field. ● The ball will start play at the 45-yard line - game start and turnovers. ● The direction of offensive play will go towards the existing end zones. ● If a ball is intercepted: the defender needs to only return the interception to the 45-yard line to be considered a Defensive touchdown. Team Size and Groupings ● Each team has nine players on the field (9 on 9). ● A team can play with eight if it chooses, losing an eligible receiver on offense and non line-men on defense. ● If a team is two players short, it will automatically forfeit the game. However, the opposing coach may lend players in order to allow the game to be played as a scrimmage. The officials will call the game as if it were a regular game. ● Age ranges can be defined as common age groupings (9-and-under, 12-and under) or school grades (K-2, junior high), based on the decision of each organization. -

Ohio Tiger Trap

The Professional Football Researchers Association Camp and his Followers American Football 1876-1889 By PFRA Research Originally Published in The Journey to Camp: The Origins of American Football to 1889 (PFRA Books) Tell one important fact about Walter Camp. In the fall of 1876, Yale was in the throes of learning a new game. The beating they'd been handed by Harvard the year before still If your answer is that he invented All-American teams, go to the smarted, and the Elis were determined to see it didn't happen foot of the class. again. No more halfway, concessionary rules! Yale planned on playing straight rugby and knocking the hell out of Harvard. All-American football teams have produced inumerable friendly arguments among fans and more than a smidgin of honor for the Rugby was the new deal at Princeton, too. In fact, the Tigers had designees, but Camp's annual selections -- though they became much to do with the nearly overnight conversion to rugby all across the most respected -- were one of his lesser contributions to New England. W. Earle Dodge and Jotham Potter, the pair of American sport. As a matter of fact, he didn't invent the idea of All- Princetonians who watched Harvard lick Yale in 1875, had American teams at all. succeeded in selling the rugby game to their own campus, a feat only slightly inferior to selling refrigerators to Eskimos. As Princeton Instead, he invented American football. went, so should everybody else, figured Messrs. Dodge and Potter. They fired off invitations to Harvard, Yale, and Columbia, inviting A Natural them to Springfield, Massachusetts, so they could all sit down and Walter Camp was born April 17, 1859, in the city of New Haven, decide to play the game the way Princeton wanted to. -

RLCM-Book-31.Pdf

RLCM Endorsed By .com.au RUGBY LEAGUE COACHING MAGAZINE CONTENTS 2 How To Introduce A Left and Right Defensive Pattern By Glenn Bayliss ARL Level 3 Coach 6Wet Weather Football By Greg Platz 8 The Barbell Back Squat By Alex Corvo 10 Attacking For A Result From Scrums By Glenn Bayliss ARL Level 3 Coach 13 Shin Splints By Dr Keith Woodhead 14 Strength Training, at what age and what type? 15 Kicking Out Of Own 20 Metres For Teams With Short Kicking Games By Warren Smiles - Newcastle Knights Coaching & Development Manager 17 You Only Achieve What You Believe 20 What Is Different About A Final? By the late Darrell Chapman - ARL Level 3 Coach BOOK 3 www.rlcm.com.au Page 1 How To Introduce A Left And Right Defensive Pattern By Glenn Bayliss ARL Level 3 Coach How Does It Help? The winger and centre should then be able to develop an appreciation of each others defensive ability and Most teams playing rugby league at senior level have gradually improve their on field communication. adopted a defensive pattern of “left and right centres”. It is the most prevalent pattern used by teams due to The coach’s role is to ensure this “bond” between centre its ability to “slot” players into the defensive line and wing occurs. All training drills should see these allowing them to work with the same team mate, players paired up, even to the extent where “pairing” throughout most of the game. Another advantage is occurs during skill games. This allows players to the reduced distance between players have to cover in become familiar with each others play and quirks. -

Rookie-Rugby-Guidebook.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from USA Rugby’s CEO, Nigel Melville 1 Introduction to Rookie Rugby 2 Rugby vs. Rookie Rugby 3 Rookie Rugby Honor Code 4 Playing with Flags 5 Playing the Game 6 Game Set Up 6 Objective of the Game and Scoring 7 Moving the Ball 7 Open Play 8 Offense 8 Defense 9 Advantage 11 Flag Etiquette 12 Penalties and Restarts 13 Rookie Rugby Progression 14 Get Involved 18 Coaching Rookie Rugby 18 Refereeing Rookie Rugby 20 Resources 22 Rookie Rugby Vocabularly 23 LETTER FROM USA RUGBY’S NIGEL MELVILLE Dear Rookie Rugby Participants, USA Rugby is proud to offer Rookie Rugby as the non-contact game and starting point in our nation’s rugby development pathway. The game was invented when a young man at Rugby School in England ‘picked up the ball and ran with it’ over 150 years ago. Today, over five million people in 120 countries play the game of rugby across six continents! Rookie Rugby is designed with the American athlete in mind. It is a fun, safe, team game that develops a range of ball handling, running and evasion skills. Participants learn the importance of teamwork and respect for opponents, coaches and referees, which are key elements of all athletic endeavors. The sport of rugby is simple to understand, organize and teach. USA RUgby has created many tools to help explain the skills, rules and values associated with this special game. Whether you are a former player, long-time supporter or new to the game, you too, can be a part of Rookie Rugby! All you have to do is PICK UP THE BALL AND RUN WITH IT! Nigel Melville USA Rugby CEO and President of Rugby Operations | 1 INTRODUCTION TO ROOKIE RUGBY Rookie Rugby is a safe, non-contact, and easy to play game for boys and girls of all ages. -

Analysis of the Modern Football Crisis: Historical Perspective and Recommendation

ANALYSIS OF THE MODERN FOOTBALL CRISIS: HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE AND RECOMMENDATION Robert Ian Benedikt TC 660H Plan II Honors Program The University of Texas at Austin December 13, 2017 Daron K. Roberts Center for Sports Leadership and Innovation Supervising Professor George S. Christian, Ph.D. Department of English Second Reader 1 ABSTRACT Author: Robert I. Benedikt Title: Analysis of the Modern Football Crisis: Historical Perspective and Recommendation Supervising Professor: Daron K. Roberts The modern football crisis details the concussion problem currently occurring across every facet of American football, from the professional level all the way down to the youth game. A contemporary and polarizing topic, concussions in football has led many to question whether the game can survive in its present form for future generations. Can football become safer and adapt to survive this current dilemma? To understand and evaluate this problem I will first go back in time to the turn of the twentieth-century. I will analyze the history of the game and a similar health crisis that occurred in collegiate football in the early 1900s. I will then compare and contrast the twentieth-century crisis to the modern one, and analyze what lessons were learned and what can be applied in attempting to solve the concussion issue. Lastly, I will offer my own safety recommendations for the game, and provide hope that this issue can be solved to ensure football’s survive for the foreseeable future. 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS To my parents, thank you for everything. It has not always been easy, but you have stuck with me through thick and thin. -

The Development of the American Scrimmage System: a Discussion

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 24, No. 2 (2002) The Development of the American Scrimmage System: A Discussion By Ian Speers The development of the American scrimmage system in the early years of the game marked the first significant departure of American football from its Rugby parent, and has had a lasting effect upon the American game since that time, and would later have a similar effect upon Canadian football. The secondary historical accounts of the development of this innovation are surprisingly brief, giving the impression that the point of divergence of the American game from Rugby can be dated to 12 October 1880: the day that Walter Camp persuaded the American Intercollegiate teams to accept the following "snap-back" rule, which he is alleged to have drafted personally: A scrimmage takes place when the holder of the ball, being in the field of play, puts it down in front of him and puts it in play (while on-side) by-- 1st, kicking the ball; 2nd, by snapping it back with the foot. The man who first receives the ball from the snap-back shall be called the quarter-back, and shall not then rush forward with the ball under penalty of a foul. This rule has lately been interpreted as the sole innovation of Walter Camp, and is reported in most recent histories as marking the first departure of American football from the game of Rugby Union. By eliminating the old-style Rugby scrum and replacing it with the more open scrimmage system, many historians have argued that Camp single-handedly directed American football away from its English parent. -

A History of the Presentation of American Football in England and Germany

FROM VIOLENCE TO PARTY: A HISTORY OF THE PRESENTATION OF AMERICAN FOOTBALL IN ENGLAND AND GERMANY DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Lars Dzikus, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Melvin L. Adelman, Adviser Professor Sarah K. Fields Adviser Professor William J. Morgan College of Education ABSTRACT While scholars have widely discussed the cultural, economic, and political influence of the United States on Europe in general and Germany in particular, the realm of sports has received surprisingly little attention. This study ties in with the scholarly debate about Americanization and / or globalization that started in the first half the 1990s. It examines the presentation of American football in England from the 1890s through World War II as well as in Germany following the war to the present day. The study discusses what non-Americans wrote about football and what their countrymen and –women read about it. The study draws on English and German newspapers and magazines, particularly the London Times and the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. It also examines the role American military, radio, television, and movies played in the diffusion of American football. In the case of Germany, the researcher draws on extensive qualitative interviews with several of the “founding fathers” of American football in Germany as well as his own experiences in the sport. The work demonstrates that American football arrived in Germany on a field that had been prepared by a three-hundred-year process of imagining Amerika. -

Rules of Rugby League

ARL Rules book 2017 Copy3 SPC 1171219.qxp_ARL Rules book 2012 7/2/17 10:38 am Page 1 2 0 1 7 E D IT IO N RUGBY LEAGUE LAWS OF THE GAME INTERNATIONAL LEVEL WITH NOTES ON THE LAWS AND NRL TELSTRA PREMIERSHIP INTERPRETATIONS (APPROVED BY THE AUSTRALIAN RUGBY LEAGUE COMMISSION) OFFICIAL FEBRUARY 2017 ARL Rules book 2017 Copy3 SPC 1171219.qxp_ARL Rules book 2012 7/2/17 10:38 am Page 2 PLEASE NOTE THE NOTES ON THE LAWS ACCOMPANYING EACH SECTION ARE TO BE TAKEN AS OFFICIAL INSTRUCTIONS RELATING TO THE PUBLICATION AND INTERPRETATION OF THE LAWS. This publication replaces all existing Law Books, Manuals, etc., and is the only official NRL publication as at this date. FEBRUARY 2017 © N.R.L. 2017 ARL Rules book 2017 Copy3 SPC 1171219.qxp_ARL Rules book 2012 7/2/17 10:38 am Page 1 RUGBY LEAGUE LAWS OF THE GAME INTERNATIONAL LEVEL WITH NOTES ON THE LAWS AND NRL TELSTRA PREMIERSHIP INTERPRETATIONS (Approved by the AustrAliAn rugby leAgue Commission) Page SECTION 1 Playing Field...............................................................2 SECTION 2 Glossary......................................................................4 SECTION 3 Ball.............................................................................. 8 SECTION 4 Player and Players’ Equipment................................ 9 SECTION 5 Mode of Play............................................................ 11 SECTION 6 Scoring..................................................................... 12 SECTION 7 Timekeeping.............................................................16