Ohio Tiger Trap

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1951 Grizzly Football Yearbook University of Montana—Missoula

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Grizzly Football Yearbook, 1939-2014 Intercollegiate Athletics 9-1-1951 1951 Grizzly Football Yearbook University of Montana—Missoula. Athletics Department Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/grizzlyfootball_yearbooks Recommended Citation University of Montana—Missoula. Athletics Department, "1951 Grizzly Football Yearbook" (1951). Grizzly Football Yearbook, 1939-2014. 5. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/grizzlyfootball_yearbooks/5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Intercollegiate Athletics at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Grizzly Football Yearbook, 1939-2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TABLE OF CONTENTS Press and Radio Information.......................... 1 Mountain States Conference Schedule . c ............... 2 1951 Schedule, 1950 Results, All-Time Record............ 3 General Information on Montana University............. U The 1951 Grizzly Coaching Staff....................... 5 1951 Outlook....................................... 8 1951 Football Roster................................ 10 Thumbnail Sketches of Flayers....................... 12 Pronunciation...................................... 18 Squad Summary By Positions........................... 19 Experience Breakdown................................ 20 Miscellaneous................................... -

Front Matter

Ingrassia_Gridiron 11/6/15 12:22 PM Page vii © University Press of Kansas. All rights reserved. Reproduction and distribution prohibited without permission of the Press. Contents List of Illustrations ix Acknowledgments xi INTRODUCTION The Cultural Cornerstone of the Ivory Tower 1 CHAPTER ONE Physical Culture, Discipline, and Higher Education in 1800s America 14 CHAPTER TWO Progressive Era Universities and Football Reform 40 CHAPTER THREE Psychologists: Body, Mind, and the Creation of Discipline 71 CHAPTER FOUR Social Scientists: Making Sport Safe for a Rational Public 93 CHAPTER FIVE Coaches: In the Disciplinary Arena 115 CHAPTER SIX Stadiums: Between Campus and Culture 139 CHAPTER SEVEN Academic Backlash in the Post–World War I Era 171 EPILOGUE A Circus or a Sideshow? 200 Ingrassia_Gridiron 11/6/15 12:22 PM Page viii © University Press of Kansas. All rights reserved. Reproduction and distribution prohibited without permission of the Press. viii Contents Notes 207 Bibliography 269 Index 305 Ingrassia_Gridiron 11/6/15 12:22 PM Page ix © University Press of Kansas. All rights reserved. Reproduction and distribution prohibited without permission of the Press. Illustrations 1. Opening ceremony, Leland Stanford Junior University, October 1891 2 2. Walter Camp, captain of the Yale football team, circa 1880 35 3. Grant Field at Georgia Tech, 1920 41 4. Stagg Field at the University of Chicago 43 5. William Rainey Harper built the University of Chicago’s academic reputation and also initiated big-time athletics at the institution 55 6. Army-Navy game at the Polo Grounds in New York, 1916 68 7. G. T. W. Patrick in 1878, before earning his doctorate in philosophy under G. -

Hinkey Haines: the Giants' First Superstar

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 4, No. 2 (1982) HINKEY HAINES: THE GIANTS' FIRST SUPERSTAR By C.C. Staph Oh Hinkey Haines, oh Hinkey Haines! The New York Giants' football brains. He never loses, always gains. Oh Hinkey Haines, oh Hinkey Haines! -- anonymous New York sportswriter, 1926 Hinkey Haines was one of those running backs who blaze across the NFL sky for only a short time, yet burn so brightly that they are honored long after their last touchdown. Gale Sayers is a recent example; George McAfee was another. Haines completed his playing career before the league began keeping statistics. As a consequence, he is remembered not for huge yardage totals but for brilliant individual performances. During his short but spectacular career, he put together enough outstanding plays to be ranked with Grange, Driscoll, and Nevers as one of the great runners of his time. He was a phenomenal breakaway runner, famous for his speed. Bob Folwell, the New York Giants' first coach, insisted that in his twenty years of coaching he had never seen a faster man on the gridiron than Haines. If he were playing today, he would almost surely be turned into a wide receiver. Even in those rather pass-sparse days, Hinkey scored several of his most spectacular touchdowns on passes. On punt and kickoff returns, he was deadly. He joined the Giants in 1925 at the comparatively ripe age of 26. For four years, he was the toast of New York. He put in one more season with the Staten Island Stapletons and then retired. He was lured back in 1931 as player-coach of the Stapes, but, at 32, he played only sparingly. -

TIMELINE of YALE FOOTBALL Updated As of February 2018

TIMELINE OF YALE FOOTBALL Updated as of February 2018 Oct. 31, 1872 David Schley Schaff, Elliot S. Miller, Samuel Elder and other members of the class of 1873 call a meeting of the Yale student body. From it emerges the Yale Football Association, the first formal entity to govern the game at Yale. Schaff is elected president and team captain. Nov. 16, 1872 With faculty approval, Yale meets Columbia, the nearest football-playing college, at Hamilton Park in New Haven. The game is essentially soccer with 20-man sides, played on a field 400 by 250 feet. Yale wins 3-0, Tommy Sherman scoring the first goal and Lew Irwin the other two. Nov. 15, 1873 Yale and Princeton inaugurate what will become Yale’s longest rivalry. Princeton wins 3 goals to 0. Nov. 13, 1875 Yale and Harvard meet for the first time at Hamilton Park. The game is played under the so-called “concessionary rules”—15 players on a side and running with the ball permitted as in rugby, a round ball and only goals counting as in soccer. A crowd of 2,000 pays 50 cents a head—twice the normal price for a Yale game—to watch Harvard win 4-0. 1880 Walter Camp, in his third year as Yale’s delegate at the Intercollegiate Football Association rules convention, persuades the meeting to accept 11-man, rather than 15-man, sides. He also replaces rugby’s scrum with the scrimmage, which “takes place when the holder of the ball…puts it down on the ground in front of him and puts it in play by snapping it back with his foot.” Nov. -

Glenn Killinger, Service Football, and the Birth

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School School of Humanities WAR SEASONS: GLENN KILLINGER, SERVICE FOOTBALL, AND THE BIRTH OF THE AMERICAN HERO IN POSTWAR AMERICAN CULTURE A Dissertation in American Studies by Todd M. Mealy © 2018 Todd M. Mealy Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2018 ii This dissertation of Todd M. Mealy was reviewed and approved by the following: Charles P. Kupfer Associate Professor of American Studies Dissertation Adviser Chair of Committee Simon Bronner Distinguished Professor Emeritus of American Studies and Folklore Raffy Luquis Associate Professor of Health Education, Behavioral Science and Educaiton Program Peter Kareithi Special Member, Associate Professor of Communications, The Pennsylvania State University John Haddad Professor of American Studies and Chair, American Studies Program *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT This dissertation examines Glenn Killinger’s career as a three-sport star at Penn State. The thrills and fascinations of his athletic exploits were chronicled by the mass media beginning in 1917 through the 1920s in a way that addressed the central themes of the mythic Great American Novel. Killinger’s personal and public life matched the cultural medley that defined the nation in the first quarter of the twentieth-century. His life plays outs as if it were a Horatio Alger novel, as the anxieties over turn-of-the- century immigration and urbanization, the uncertainty of commercializing formerly amateur sports, social unrest that challenged the status quo, and the resiliency of the individual confronting challenges of World War I, sport, and social alienation. -

04 FB Guide.Qxp

Stanford legend Ernie Nevers Coaching Records Football History Stanford Coaching History Coaching Records Seasons Coach Years Won Lost Tied Pct. Points Opp. Seasons Coach Years Won Lost Tied Pct. Points Opp. 1891 No Coach 1 3 1 0 .750 52 26 1933-39 C.E. Thornhill 7 35 25 7 .574 745 499 1892, ’94-95 Walter Camp 3 11 3 3 .735 178 89 1940-41 Clark Shaughnessy 2 16 3 0 .842 356 180 1893 Pop Bliss 1 8 0 1 .944 284 17 1942, ’46-50 Marchmont Schwartz 6 28 28 4 .500 1,217 886 1896, 98 H.P. Cross 2 7 4 2 .615 123 66 1951-57 Charles A. Taylor 7 40 29 2 .577 1,429 1,290 1897 G.H. Brooke 1 4 1 0 .800 54 26 1958-62 Jack C. Curtice 5 14 36 0 .280 665 1,078 1899 Burr Chamberlain 1 2 5 2 .333 61 78 1963-71 John Ralston 9 55 36 3 .601 1,975 1,486 1900 Fielding H. Yost 1 7 2 1 .750 154 20 1972-76 Jack Christiansen 5 30 22 3 .573 1,268 1,214 1901 C.M. Fickert 1 3 2 2 .571 34 57 1979 Rod Dowhower 1 5 5 1 .500 259 239 1902 C.L. Clemans 1 6 1 0 .857 111 37 1980-83 Paul Wiggin 4 16 28 0 .364 1,113 1,146 1903-08 James F. Lanagan 6 49 10 5 .804 981 190 1984-88 Jack Elway 5 25 29 2 .463 1,263 1,267 1909-12 George Presley 4 30 8 1 .782 745 159 1989-91 Dennis Green 3 16 18 0 .471 801 770 1913-16 Floyd C. -

Walter Camp Football Foundation Announces 2017 All-America Teams It Is the 128Th Edition of the Nation’S Oldest All-America Team

For Immediate Release: December 7, 2017 Contact: Al Carbone (203) 671-4421 Follow us on Twitter @WalterCampFF Walter Camp Football Foundation Announces 2017 All-America Teams It is the 128th edition of the nation’s oldest All-America Team NEW HAVEN, CT – Led by 2017 Player of the Year Baker Mayfield, second-ranked Oklahoma has four players on the Walter Camp Football Foundation All-America Teams, the 128th honored by the organization. The nation’s oldest All-America squad was announced this evening on The Home Depot ESPN College Football Awards Show. In all, 33 different schools from nine conferences (including independents) were represented on the All-America First and Second Teams (a total of 52 players selected). Auburn had three honorees (1 First Team and 2 Second Team). Wisconsin had four Second Team All-America honorees, while top-ranked Clemson had three. Overall, the Atlantic Coast Conference had the most honorees (11), followed by the Big Ten (10) and Big 12 (9). The Walter Camp All-America teams are selected by the head coaches and sports information directors of the 130 Football Bowl Subdivision schools and certified by Marcum LLP, a New Haven-based accounting firm. Walter Camp Football Foundation President Michael Madera was pleased with the voting participation. “Once again, we had more than 80 percent of the FBS schools participate in this year’s voting,” Madera said. “We are very appreciative of the continuing cooperation of the coaches and sports information directors in our annual effort to honor the nation’s most outstanding college players.” Leading the First Team offensive unit is Mayfield, a senior quarterback who was also selected the 2017 Walter Camp Player of the Year. -

Position-Specific Rugby Skills Handbook About This Handbook

POSITION-SPECIFIC RUGBY SKILLS HANDBOOK ABOUT THIS HANDBOOK Thank you for downloading the Ruck Science position-specifc rugby skills handbook. This handbook is designed for amateur rugby players, coaches and parents as a guide to creating tailored training programs that meet the needs of each individual position on a rugby team. The handbook will take readers through the specifc physical and technical demands of each position as well as the training associated with building the requisite skill set. We would like to use this opportunity to thank several organizations without whom this handbook would not have been possible. Firstly, the Canadian Rugby Union who created a similar guide in 2009. This version has drawn a lot of inspiration from that original work which was itself a derivative of a manual set up by the English Rugby Union. Secondly, the writing team of Tudor Bompa & Frederick Claro whose trans-formative work Periodization in Rugby was also published in 2009. “Periodization in Rugby” is, without a doubt, the most complete analysis of periodized training for amateur rugby players and should be essential reading for all rugby coaches who are working with young players. Sincerely, Tim Howard Founder Ruck Science TABLE OF CONTENTS 2. About this handbook 4. Physical preparation for rugby 5. Warming up 5. Cooling down 6. Key rugby skills 6. Healthy eating 7. Prop 15. Hooker 21. Lock 27. Flanker 36. Number 8 42. Scrumhalf 47. Flyhalf 52. Center 56. Wing 61. Fullback Riekert Hattingh SEATTLE SEAWOLVES RUGBY SHORTS WITH POCKETS The world’s most comfortable rugby shorts, with deep, strong pockets on both sides. -

RUGBY GENERAL DESCRIPTION of the GAME Rugby Is Played at a Fast Pace, with Few Stoppages and Continuous Possession Changes

RUGBY GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF THE GAME Rugby is played at a fast pace, with few stoppages and continuous possession changes. All players on the field, regardless of position, must be able to run, pass, kick and catch the ball. Likewise, all players must also be able to tackle and defend, making each position both offensive and defensive in nature. There is no blocking of the opponents like in football. A rugby match consists of two 40-minute halves. FIELD OF PLAY Rugby is played on a field, called a pitch, that is longer and wider than a football field, more like a soccer field. A typical pitch is 100 meters (110 yards) long 70 meters (75 yards) wide. Additionally, there are 10-22 meter end zones, called the in-goal area, behind the goalposts. The goalposts are 'H'-shaped cross bars located on the goal line and are the same size as American football goalposts. THE BALL The rugby ball is made of leather or other similar synthetic material that is easy to grip and does not have laces. Rugby balls are made in varying sizes (3, 4 or 5) for both youth and adult players. Like footballs, rugby balls are oval in shape, however are rounder and less pointed than footballs to minimize the erratic bounces we see in football. PLAYERS & POSITIONS A rugby team has 15 players on the field of play, both American football and soccer have 11 players on each team. In rugby, each team is numbered the exact same way. The number of each player signifies that player's position. -

Methods of Coaching to Improve Decision Making in Rugby

Methods of Coaching to Improve Decision Making in Rugby Trevor Allen Thesis presented for the degree of Masters (Sport Science) at Stellenbosch University Study leader: Prof ES Bressan April 2007 Declaration I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work, and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part, submitted it to any university for a degree. _______________________________ ____________ Signature Date i Abstract The purpose of this study was to describe the different methods used by coaches to improve decision making in ruby. The study included three coaches from the Western Cape area. Two of the three coaches worked with U/20A league teams and the third coach worked in the Super A league. Eight coaching sessions were video taped and analysed to identify the coaching method used when presenting skill development activities. The verbal behaviour each coach was also recorded. Five rugby games involving each of the teams were also analysed to determine which team had the highest success rates in key categories. The results showed that Coach 1 integrated decision making with skill practice primarily through the method of verbal feedback during sessions where he used a direct teaching style. His comments to players during technical skill instruction were focussed on linking their skill performance to its tactical use in a game. The other two coaches followed the expected pattern of using indirect teaching styles to teach players how to apply tactics. It was concluded that different coaches may use different teaching styles to improve players’ decision making. -

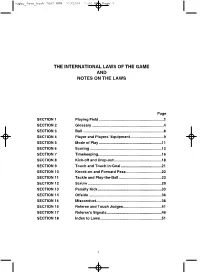

The International Laws of the Game and Notes on the Laws

rugby_laws_book 2002 NEW 11/3/04 1:00 PM Page 1 THE INTERNATIONAL LAWS OF THE GAME AND NOTES ON THE LAWS Page SECTION 1 Playing Field ..............................................................2 SECTION 2 Glossary .....................................................................4 SECTION 3 Ball ..............................................................................8 SECTION 4 Player and Players’ Equipment ................................9 SECTION 5 Mode of Play ............................................................11 SECTION 6 Scoring .....................................................................12 SECTION 7 Timekeeping.............................................................16 SECTION 8 Kick-off and Drop-out..............................................18 SECTION 9 Touch and Touch in-Goal .......................................21 SECTION 10 Knock-on and Forward Pass ..................................22 SECTION 11 Tackle and Play-the-Ball .........................................23 SECTION 12 Scrum .......................................................................29 SECTION 13 Penalty Kick .............................................................33 SECTION 14 Offside ......................................................................36 SECTION 15 Misconduct...............................................................38 SECTION 16 Referee and Touch Judges.....................................41 SECTION 17 Referee’s Signals.....................................................46 SECTION 18 Index -

Attacking 22 Entries in Rugby Union: Running Demands and Differences Between Successful and Unsuccessful Entries

Accepted: 14 November 2016 DOI: 10.1111/sms.12816 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Attacking 22 entries in rugby union: running demands and differences between successful and unsuccessful entries P. Tierney1,2 | D. P. Tobin1 | C. Blake2 | E. Delahunt1,3 1Leinster Rugby, Dublin, Ireland Global Positioning System (GPS) technology is commonly utilized in team sports, 2School of Public Health, Physiotherapy and Sports Science, University College Dublin, including rugby union. It has been used to describe the average running demands of Dublin, Ireland rugby union. This has afforded an enhanced understanding of the physical fitness 3Institute for Sport and Health, University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland requirements for players. However, research in team sports has suggested that train- ing players relative to average demands may underprepare them for certain scenarios Correspondence Peter Tierney, Leinster Rugby, Dublin, Ireland. within the game. To date, no research has investigated the running demands of at- Email: [email protected] tacking 22 entries in rugby union. Additionally, no research has been undertaken to determine whether differences exist in the running intensity of successful and unsuc- cessful attacking 22 entries in rugby union. The first aim of this study was to describe the running intensity of attacking 22 entries. The second aim of this study was to investigate whether differences exist in the running intensity of successful and un- successful attacking 22 entries. Running intensity was measured using meters per minute (m min−1) for (a) total distance, (b) running distance, (c) high- speed running distance, and (d) very high- speed running distance. This study provides normative data for the running intensity of attacking 22 entries in rugby union.