Shaping the Scrum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Herdenking WO I – David Gallaher Kapitein “All Blacks”

Herdenking WO I – David Gallaher kapitein “All Blacks” Op zaterdag 3 oktober 2015 wordt er op het grondgebied van het Memorial Museum Passchendaele 1917, een rugbywedstrijd gespeeld tussen New Zealand Army en de Belgische nationale mannenploeg, de Zwarte Duivels. Deze wedstrijd wordt georganiseerd als herdenking aan de toenmalige kapitein van de All-Blacks, David Gallaher, die in de Eerste Wereldoorlog in Passendaele sneuvelde. De organisatie is een samenwerking tussen de Nieuw-Zeelandse ambassade, de Vlaamse Rugbybond, de Belgische Rugbybond en het Memorial Museum Passchendaele 1917 Voorgeschiedenis In 1905 deden de “All Blacks”, die tot dan nog de “Originals” werden genoemd, hun veelbesproken tour in Europa, met als kapitein David Gallaher. De Nieuw-Zeelanders waren zo goed dat een reporter schreef: “they played as all backs”. Maar door een spellingfout stond er boven het artikel “they played as All Blacks”. Een mythe was geboren. De “All Blacks” wonnen al hun Europese wedstrijden, met uitzondering van één wedstrijd tegen Wales. Nieuw-Zeeland in Passendale Midden september 1917 werd het Australian en New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) naar Vlaanderen gehaald voor de verovering van Passendale. Op 4 oktober zorgden de Nieuw- Zeelanders voor een doorbraak op ’s Graventafel, terwijl de Australiërs het huidige Tyne Cot Cemetery innamen. Op 9 oktober probeerden Britse troepen tevergeefs verder vooruit te komen, opnieuw gevolgd door het ANZAC op 12 oktober. In deze bloedige gevechten verloren de Kiwi’s in minder dan vier uur tijd 2700 soldaten, wat een enorm hoge tol was voor het nog jonge Nieuw- Zeeland. Ter nagedachtenis van de ANZAC- troepen die hier in september en oktober 1917 een bloedige strijd geleverd hebben, wordt er van 2 tot 4 oktober 2015, een speciaal ANZAC weekend, georganiseerd. -

Legacy – the All Blacks

LEGACY WHAT THE ALL BLACKS CAN TEACH US ABOUT THE BUSINESS OF LIFE LEGACY 15 LESSONS IN LEADERSHIP JAMES KERR Constable • London Constable & Robinson Ltd 55-56 Russell Square London WC1B 4HP www.constablerobinson.com First published in the UK by Constable, an imprint of Constable & Robinson Ltd., 2013 Copyright © James Kerr, 2013 Every effort has been made to obtain the necessary permissions with reference to copyright material, both illustrative and quoted. We apologise for any omissions in this respect and will be pleased to make the appropriate acknowledgements in any future edition. The right of James Kerr to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. A copy of the British Library Cataloguing in Publication data is available from the British Library ISBN 978-1-47210-353-6 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-47210-490-8 (ebook) Printed and bound in the UK 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 Cover design: www.aesopagency.com The Challenge When the opposition line up against the New Zealand national rugby team – the All Blacks – they face the haka, the highly ritualized challenge thrown down by one group of warriors to another. -

Rugby's Rise in the United States: the Impact of Social Media on an Emerging Sport

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2014-11-01 Rugby's Rise in the United States: The Impact of Social Media On An Emerging Sport Benjamin James Kocher Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Communication Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Kocher, Benjamin James, "Rugby's Rise in the United States: The Impact of Social Media On An Emerging Sport" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. 4332. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4332 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Rugby’s Rise in the United States: The Impact of Social Media on an Emerging Sport Benjamin Kocher A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Jared Johnson, Chair Clark Callahan Dale Cressman Department of Communications Brigham Young University November 2014 Copyright © 2014 Benjamin Kocher All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Rugby’s Rise in the United States: The Impact of Social Media on an Emerging Sport Benjamin Kocher Department of Communications, BYU Master of Arts In this study, the grounded theory approach was used to conduct a qualitative study about the effects the media has on rugby players in the United States. This study involved in-depth interviews with American-born-and-raised rugby players from the top rugby colleges and universities in the United States. -

Position-Specific Rugby Skills Handbook About This Handbook

POSITION-SPECIFIC RUGBY SKILLS HANDBOOK ABOUT THIS HANDBOOK Thank you for downloading the Ruck Science position-specifc rugby skills handbook. This handbook is designed for amateur rugby players, coaches and parents as a guide to creating tailored training programs that meet the needs of each individual position on a rugby team. The handbook will take readers through the specifc physical and technical demands of each position as well as the training associated with building the requisite skill set. We would like to use this opportunity to thank several organizations without whom this handbook would not have been possible. Firstly, the Canadian Rugby Union who created a similar guide in 2009. This version has drawn a lot of inspiration from that original work which was itself a derivative of a manual set up by the English Rugby Union. Secondly, the writing team of Tudor Bompa & Frederick Claro whose trans-formative work Periodization in Rugby was also published in 2009. “Periodization in Rugby” is, without a doubt, the most complete analysis of periodized training for amateur rugby players and should be essential reading for all rugby coaches who are working with young players. Sincerely, Tim Howard Founder Ruck Science TABLE OF CONTENTS 2. About this handbook 4. Physical preparation for rugby 5. Warming up 5. Cooling down 6. Key rugby skills 6. Healthy eating 7. Prop 15. Hooker 21. Lock 27. Flanker 36. Number 8 42. Scrumhalf 47. Flyhalf 52. Center 56. Wing 61. Fullback Riekert Hattingh SEATTLE SEAWOLVES RUGBY SHORTS WITH POCKETS The world’s most comfortable rugby shorts, with deep, strong pockets on both sides. -

Here We Come 14

“For anyone who is interested in looking beyond the names, the dates, the half-truths and the mythologies and entering the realm of rugby’s place in our history, this is a must read.” — Chris Laidlaw Rugby is New Zealand’s national sport. From the grand tour by the 1888 Natives to the upcoming 2015 World Cup, from games in the North African desert in World War II to matches behind barbed wire during the 1981 Springbok tour, from grassroots club rugby to heaving crowds outside Eden Park, Lancaster Park, Athletic Park or Carisbrook, New Zealanders have made rugby their game. In this book, historian and former journalist Ron Palenski tells the full story of rugby in New Zealand for the first time. It is a story of how the game travelled from England and settled in the colony, how Ma¯ori and later Pacific players made rugby their own, how battles over amateurism and apartheid threatened the sport, how national teams, provinces and local clubs shaped it. But above all it is a story of wing forwards and fullbacks, of Don Clarke and Jonah Lomu, of the Log of Wood and Charlie Saxton’s ABC, of supporters in the grandstand and crackling radios at 2 a.m. Ron Palenski is an author and historian and among the most recognised authorities on the history of sport, and especially rugby, in New Zealand. He has written numerous books, among them an academic study, The Making of New Zealanders, that placed rugby firmly as a marker in national identity. Contents Acknowledgements 9. -

From Chronology to Confessional: New Zealand Sporting Biographies in Transition

From Chronology to Confessional: New Zealand Sporting Biographies in Transition GEOFF WATSON Abstract Formerly rather uniform in pattern, sporting biographies have evolved significantly since the 1970s, becoming much more open in their criticism of teammates and administrators as well as being more revealing of their subject’s private lives. This article identifies three transitional phases in the genre; a chronological era, extending from the early twentieth century until the 1960s; an indirectly confessional phase between the 1970s and mid 1980s and an openly confessional phase from the mid-1980s. Despite these changes, sporting biographies continue to reinforce the dominant narratives around sport in New Zealand. New Zealand sporting biographies have a mixed reputation in literary and scholarly circles. Often denigrated for their allegedly formulaic style, they have also been criticised for their lack of insight into New Zealand society.1 Representative of this critique is Lloyd Jones, who wrote in 1999, “sport hardly earns a mention in our wider literature, and … the rest of society is rarely, if ever, admitted to our sports literature.”2 This article examines this perspective, arguing that sporting biographies afford a valuable insight into New Zealand’s changing self- image and values. Moreover, it will be argued that the nature of sporting biographies themselves has changed significantly since the 1980s and that they have become much more open in their discussion of teammates and the personal lives of their subjects. Whatever one’s perspective on the literary merits of sporting biographies, their popular appeal is undeniable. Whereas the print run of most scholarly texts in New Zealand is at best a few thousand, sporting biographies consistently sell in the tens of thousands. -

Einführung in Die Grundlegende Terminologie Der Sportart Rugby

Masterarbeit Am Institut für Angewandte Linguistik und Translatologie der Universität Leipzig über das Thema Einführung in die grundlegende Terminologie der Sportart Rugby vorgelegt von Lisa Marie Nagel Matrikelnummer: 3273980 Referent: Klaus Ahting Korreferent: Dr. Harald Scheel Leipzig 06.08.2019 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Einleitung ............................................................................................................... 1 2 Thematische Einführung zur Sportart Rugby ........................................................ 3 2.1 Rugby – Die Sportart .......................................................................................... 3 2.1.1 Entstehung und Entwicklung .............................................................................. 3 2.1.2 Rugbykultur ........................................................................................................ 6 2.1.3 Spielfeld und Spielvoraussetzungen ................................................................... 8 2.1.4 Grundidee und Spielverlauf .............................................................................. 12 2.1.5 Spielformen ...................................................................................................... 13 2.1.5.1 Rugby Union ................................................................................................ 14 2.1.5.2 Siebener-Rugby ........................................................................................... 17 2.1.5.3 Weitere Spielformen ................................................................................... -

RUGBY GENERAL DESCRIPTION of the GAME Rugby Is Played at a Fast Pace, with Few Stoppages and Continuous Possession Changes

RUGBY GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF THE GAME Rugby is played at a fast pace, with few stoppages and continuous possession changes. All players on the field, regardless of position, must be able to run, pass, kick and catch the ball. Likewise, all players must also be able to tackle and defend, making each position both offensive and defensive in nature. There is no blocking of the opponents like in football. A rugby match consists of two 40-minute halves. FIELD OF PLAY Rugby is played on a field, called a pitch, that is longer and wider than a football field, more like a soccer field. A typical pitch is 100 meters (110 yards) long 70 meters (75 yards) wide. Additionally, there are 10-22 meter end zones, called the in-goal area, behind the goalposts. The goalposts are 'H'-shaped cross bars located on the goal line and are the same size as American football goalposts. THE BALL The rugby ball is made of leather or other similar synthetic material that is easy to grip and does not have laces. Rugby balls are made in varying sizes (3, 4 or 5) for both youth and adult players. Like footballs, rugby balls are oval in shape, however are rounder and less pointed than footballs to minimize the erratic bounces we see in football. PLAYERS & POSITIONS A rugby team has 15 players on the field of play, both American football and soccer have 11 players on each team. In rugby, each team is numbered the exact same way. The number of each player signifies that player's position. -

Methods of Coaching to Improve Decision Making in Rugby

Methods of Coaching to Improve Decision Making in Rugby Trevor Allen Thesis presented for the degree of Masters (Sport Science) at Stellenbosch University Study leader: Prof ES Bressan April 2007 Declaration I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work, and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part, submitted it to any university for a degree. _______________________________ ____________ Signature Date i Abstract The purpose of this study was to describe the different methods used by coaches to improve decision making in ruby. The study included three coaches from the Western Cape area. Two of the three coaches worked with U/20A league teams and the third coach worked in the Super A league. Eight coaching sessions were video taped and analysed to identify the coaching method used when presenting skill development activities. The verbal behaviour each coach was also recorded. Five rugby games involving each of the teams were also analysed to determine which team had the highest success rates in key categories. The results showed that Coach 1 integrated decision making with skill practice primarily through the method of verbal feedback during sessions where he used a direct teaching style. His comments to players during technical skill instruction were focussed on linking their skill performance to its tactical use in a game. The other two coaches followed the expected pattern of using indirect teaching styles to teach players how to apply tactics. It was concluded that different coaches may use different teaching styles to improve players’ decision making. -

Evidence from Rugby's Six Nations Championship

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Hogan, Vincent; Massey, Patrick Working Paper Teams' reponses to changed incentives: Evidence from Rugby's Six Nations Championship UCD Centre for Economic Research Working Paper Series, No. WP15/18 Provided in Cooperation with: UCD School of Economics, University College Dublin (UCD) Suggested Citation: Hogan, Vincent; Massey, Patrick (2015) : Teams' reponses to changed incentives: Evidence from Rugby's Six Nations Championship, UCD Centre for Economic Research Working Paper Series, No. WP15/18, University College Dublin, UCD School of Economics, Dublin This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/129334 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been -

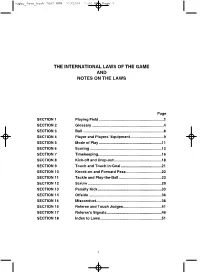

The International Laws of the Game and Notes on the Laws

rugby_laws_book 2002 NEW 11/3/04 1:00 PM Page 1 THE INTERNATIONAL LAWS OF THE GAME AND NOTES ON THE LAWS Page SECTION 1 Playing Field ..............................................................2 SECTION 2 Glossary .....................................................................4 SECTION 3 Ball ..............................................................................8 SECTION 4 Player and Players’ Equipment ................................9 SECTION 5 Mode of Play ............................................................11 SECTION 6 Scoring .....................................................................12 SECTION 7 Timekeeping.............................................................16 SECTION 8 Kick-off and Drop-out..............................................18 SECTION 9 Touch and Touch in-Goal .......................................21 SECTION 10 Knock-on and Forward Pass ..................................22 SECTION 11 Tackle and Play-the-Ball .........................................23 SECTION 12 Scrum .......................................................................29 SECTION 13 Penalty Kick .............................................................33 SECTION 14 Offside ......................................................................36 SECTION 15 Misconduct...............................................................38 SECTION 16 Referee and Touch Judges.....................................41 SECTION 17 Referee’s Signals.....................................................46 SECTION 18 Index -

Memorial Unveiled to ‘Original’ All Black in Donegal

Memorial unveiled to ‘Original’ All Black in Donegal Sir Jerry Mateparae and IRFU President Philip Orr recently unveiled Ramelton’s memorial to Dave Gallaher, Captain of the ‘Original’ All Blacks, to mark the 100th anniversary of the legendary player’s death at the Battle of Passchendaele in 1917. Born in Ramelton, Dave Gallaher’s family emigrated to the Bay of Plenty, New Zealand in 1878 as part of the Vesey-Stewart Special Settlement Scheme. Dave was five years old. They settled in Katikati, on the North Island where David’s mother Maria, became the local schoolteacher. Maria died in 1887 at the tragically young age of 42, leaving 11 children without a mother. Two years later, the 17-year old Dave Gallaher moved to Auckland and played rugby – first for the Parnell Club and then the Ponsonby Club from 1896. In that year he also debuted at provincial level. His rugby career was interrupted when in 1901, he joined the New Zealand Contingent of Mounted Rifles to fight in the Boer War. Gallaher is revered as the captain of the 1905/06 New Zealand touring team (the first to be known as the All Blacks) that won 34 out of 35 matches during that tour, setting a high standard for all future All Blacks teams to follow. During the First World War, 43 year old Gallaher enlisted in the 2nd Battalion, Auckland Regiment within the New Zealand Division to fight in Europe. At the Battle of Passchendaele he was shot in the face during the attack on Gravenstafel Spur, Belgium on 4 October 1917 and died later that day.