Assessing Hong Kong's Blueprint for Internationalising Higher Education1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Experience Lingnan University, Located in Tuen

e r X p i e E n c e Index e l c X Explore Hong Kong 1 E Experience 2 Excel @ 10 E X p l o r e Fast facts 11 L ingn an U ST nive ART rs HE ity RE! L ingn an U ST nive ART rs HE ity RE! Welcome to Hong Kong Experience Lingnan University, located in Tuen Mun, offers a stimulating and thought-provoking liberal arts education. We are the only university in Hong Kong to offer a dedicated liberal arts education. Our goal is to cultivate in our graduates the skills and sensibilities necessary to successfully pursue their career goals and take their place as socially responsible citizens in today’s rapidly evolving global environment. Lively and outward-looking, the university is located on an award-winning campus that visually represents our East-West orientation. Courses are offered by 16 departments in the Faculties of Arts, Business and Social Sciences, the Core Curriculum and General Education Explore Office and two language centres. Hong Kong Mission and vision Lingnan University is committed to the provision of quality education The geographical position of Hong Kong, a vibrant world city situated at the mouth of distinguished by the best liberal arts the Pearl River Delta on the coast of southern China, has made it a gateway between traditions. We adopt a whole-person East and West, turning it into one of the world’s most cosmopolitan metropolises. approach to education that enables our students to think, judge, care Bi-literacy and tri-lingualism thrive in Hong Kong. -

Table of Content

Table of Content P. 2 Welcoming Message P. 3 Co-Organizers Supporting Institutions P. 4 Background of the Conference Keynote Speakers P. 5 Plenary Speakers - Day 1 P. 6 Plenary Speakers - Day 2 Speaker - Closing Remarks P. 7 -10 Conference Schedule P. 11 Details of Keynote Speeches P. 12 -13 Details of Plenary Sessions P. 14 Details of Closing Remarks P. 14 -17 Details of Breakout Sessions P. 18 -19 Details of Poster Sessions P. 20 Exhibitions P. 21 Registration Accommodation P. 22 Meal Arrangement Dining P. 23 - 24 Transport P. 25 Information for Visitor Cultural & Tour Program Appendix P. 26 Information for Presenters P. 27 Map of Conference Venue P. 28 Map of Lingnan University 1 Welcoming Message WELCOME TO THE 6TH PAN -ASIAN INITIATIVE ON SERVICE -LEARNING & THE 2ND ASIA -PACIFIC REGIONAL CONFERENCE ON SERVICE -LEARNING Crossing Borders, Making Connections: ServiceService----LearningLearning in Diverse Communities Lingnan University, 2009 Welcome and thank you for celebrating with us this momentous occasion. We are proud to introduce the 6th Pan-Asian Initiative on Service-Learning and the 2 nd Asia-Pacific Regional Conference on Service-Learning. Co-organized by the Office of Service-Learning in Lingnan University, Lingnan Foundation, and the United Board, this event is designed to expand the awareness and recognize the importance of Service-Learning in higher education. The theme of this year’s conference is “Crossing Borders, Making Connections: Service-Learning in Diverse Communities.” It aims to further develop the concept of Service-Learning in the context of diversity and pluralism, as well as touch upon important topics, such as the ethical dimensions in Service-Learning and the relationship between Social Enterprise and Service-Learning. -

USYD Global Mobility Guide

2020 edition Global Mobility Guide Global MobilityGlobal Guide 2020 edition Why study overseas? �������������������������������������� 2 Our global mobility programs �����������������������4 Getting credit towards your course �������������9 How to apply �������������������������������������������������� 10 Our Super Exchange Partners ���������������������14 Where can I study? ����������������������������������������16 Scholarships and costs ��������������������������������22 Global Citizenship Award�����������������������������26 What’s next? ��������������������������������������������������28 #usydontour FAQs �����������������������������������������������������������������31 “Just two words: DO IT. I have not met one person who has regretted their overseas experience. It is simply not possible to live/ study overseas without gaining something out Why study overseas? of it. Whether it is new friends or important lessons learned. Usually both! Living and studying overseas is a once in a lifetime The University of Sydney has the largest global student opportunity that will change you for the better.” mobility program in Australia*� Combine study and travel to Yasmin Dowla Bachelor of Arts/Bachelor of Economics broaden your academic experience and set yourself up for University of Edinburgh, Scotland a global career� Develop the cultural competencies to work across borders, while having the experience of a lifetime� sydney.edu.au/study/overseas-programs Develop your Experience new self-confidence, ways of learning Gain a Over independence -

Guidebook for Research Postgraduate Students

GUIDEBOOK FOR RESEARCH POSTGRADUATE STUDENTS The information in this Guidebook is updated and accurate at the time of publication. Students are strongly encouraged to visit the Registry webpage on Postgraduate Programmes (http://www.ln.edu.hk/reg/pg.php) for the most updated information. In addition, letters/notices will be issued at different stages of studies by the Registry to relevant students providing them with necessary information and/or requiring them to submit necessary reports in accordance with the latest academic regulations or approved procedures. Registry August 2016 Vision, Mission and Core Values of the University In 2015, the University revised its vision, mission and core values statements and confirmed its commitment to liberal arts education, with a view to better reflecting all the major functions of the University’s activities including teaching, learning, research and community engagement. At Lingnan, liberal arts education is achieved through the University’s broad-based curriculum, close staff-student relationship, rich residential campus life and extra-curricular activities, active community service and multi-faceted workplace experience, strong alumni and community support, and global learning opportunities. Vision To excel as a leading Asian liberal arts university with international recognition, distinguished by outstanding teaching, learning, scholarship and community engagement. Mission Lingnan University is committed to • providing quality whole-person education by combining the best of Chinese and Western -

The University of Hong Kong

THE UNIVERSITY OF HONG KONG INTERNATIONAL ADMISSIONS SCHEME FOR UNDERGRADUATE ADMISSION IN SEPTEMBER 2011 GENERAL INFORMATION AND INSTRUCTIONS 1. The procedures and information in this document apply to those applicants who require a student visa / entry permit to study in Hong Kong with overseas qualification. 2. Applicants applying through this International Admissions Scheme will not be considered for undergraduate admission via other schemes / means in the same admission year. Duplicate applications will not be considered by the University and the application fees paid are non-refundable. Closing Date and Submission of Application 3. You can apply for admission online or by paper form. In case of paper application, the completed application package should be returned by post / in person to: Academic Services Office Room UG05, Upper Ground Floor, Knowles Building The University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong Office hours: Weekdays : 9:00 a.m. - 5:30 p.m. Saturdays : 9:00 a.m. - 12:30 p.m. Closed on Sundays, Public Holidays and University Holidays ( i.e. Christmas Eve, New Year’s Eve (p.m.), The day preceding Lunar New Year (p.m.) and Foundation Day (March 16)). The closing date for application is December 30, 2010. An acknowledgment letter / e-mail will be sent to you normally within two weeks after receipt of your application. If you do not hear from the University after four weeks, please check with the Academic Services Office by phone at (852) 2859 2433 or by e-mail <[email protected]> regarding your application. Application Fee 4. All applicants are required to pay an application fee of HK$300 ( for online application ) or HK$700 ( for paper application ) and the fee is non-refundable. -

Media Release Universiti Malaya Leads Top Asian

MEDIA RELEASE UNIVERSITI MALAYA LEADS TOP ASIAN UNIVERSITIES TO ADDRESS REGIONAL & GLOBAL HIGHER EDUCATION ISSUES ___________________________________________________________________________________ KUALA LUMPUR, 14 APRIL 2021 – Universiti Malaya (UM) is the first University in Malaysia to be elected to helm the Asian Universities Alliance (AUA) Executive Presidency to address regional and global higher education issues. Professor Dato’ Ir. Dr. Mohd Hamdi Abd Shukor, Vice-Chancellor of UM has been appointed as the AUA Executive President for the year 2021- 2022. UM is honoured to represent Malaysia towards sharing our expertise and contribution to regional and global challenges which are specifically related to the higher education and economic, scientific and technological development and at the same time, strengthening the collaboration between AUA’s member institutions, including top universities in the region - National University of Singapore, Tsinghua University, The University of Hong Kong and Seoul National University. “It is a great honour for UM to be entrusted with this mandate and responsibility as this signifies another milestone for UM’s many achievements throughout the years. Our most profound appreciation and credit goes to Tsinghua University for their exceptional leadership, and we look forward to their support along with other AUA’s members for the coming year”. said Professor Dato’ Ir. Dr. Mohd Hamdi Abd Shukor. “Universiti Malaya is currently embarking on a new journey towards achieving our new vision - to be a global university impacting the world. Our international counterparts remain as one of our top priorities and we welcome avenues for knowledge sharing and collaboration, as well as exploring new pathways through the creation of beneficial and innovative programmes together. -

Humanities Research Vol XIX. No. 2. 2013

Contents Contributors . iii Introduction: The World and World-Making in Art . 1 Caroline Turner and Michelle Antoinette Worlds Pictured in Contemporary Art: Planes and Connectivities . 11 Terry Smith The Precarious Ecologies of Cosmopolitanism . 27 Marsha Meskimmon Contemporaneous Traditions: The World in Indigenous Art/ Indigenous Art in the World . 47 Ian McLean Making Worlds: Art, Words and Worlds . 61 Jen Webb and Lorraine Webb Il gesto: Global Art and Italian Gesture Painting in the 1950s . 81 Mark Nicholls and Anthony White The Third Biennale of Sydney: ‘White Elephant or Red Herring?’ . 99 Anthony Gardner and Charles Green The Challenge of Uninvited Guests: Social Art at The Blue House . 117 Zara Stanhope Tolerance: The World of Yang Fudong . 135 Claire Roberts HUMANITIES RESEARCH GUEST EDITORS Caroline Turner, Michelle Antoinette and Zara Stanhope EDITORIAL BOARD Paul Pickering (Chair), Ned Curthoys, Melinda Hinkson, Kylie Message, Kate Mitchell, Peter Treager, Sharon Komidar (Managing Editor) EDITORIAL ADVISORS Tony Bennett, University of Western Sydney; James K. Chandler, University of Chicago; Deidre Coleman, University of Melbourne; W. Robert Connor, Teagle Foundation, New York; Michael Davis, University of Tasmania; Saul Dubow, University of Sussex; Christopher Forth, University of Kansas; William Fox, Center for Art and Environment, Nevada; Debjani Ganguly, The Australian National University; Margaret R. Higonnet, University of Connecticut; Caroline Humphrey, University of Cambridge; Mary Jacobus, University of Cambridge; -

2020 JMK Schools

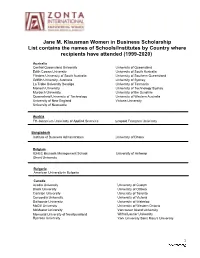

Jane M. Klausman Women in Business Scholarship List contains the names of Schools/Institutes by Country where recipients have attended (1999-2020) Australia Central Queensland University University of Queensland Edith Cowan University University of South Australia Flinders University of South Australia University of Southern Queensland Griffith University, Australia University of Sydney La Trobe University Bendigo University of Tasmania Monash University University of Technology Sydney Murdoch University University of the Sunshire Queensland University of Technology University of Western Australia University of New England Victoria University University of Newcastle Austria FH-Joanneum University of Applied Sciences Leopold Franzens University Bangladesh Institute of Business Administration University of Dhaka Belgium ICHEC Brussels Management School University of Antwerp Ghent University Bulgaria American University in Bulgaria Canada Acadia University University of Guelph Brock University University of Ottawa Carleton University University of Toronto Concordia University University of Victoria Dalhousie University University of Waterloo McGill University University of Western Ontario McMaster University Vancouver Island University Memorial University of Newfoundland Wilfrid Laurier University Ryerson University York University Saint Mary's University 1 Chile Adolfo Ibanez University University of Santiago Chile University of Chile Universidad Tecnica Federico Santa Maria Denmark Copenhagen Business School Technical University of Denmark -

Programme Overview (Updated Post-Conference, Oct 25, 2012)

Programme Overview (updated post-conference, Oct 25, 2012) 19 October 2012 (Friday) Time Schedules Registration 8.30 am – 9.00 am Venue: Foyer of Galleria Ballroom (Level 3) Welcoming Remarks Yoo Jang-Hee (President, EAEA and Chairman, National Commission for Corporate Partnership, Korea, Professor Emeritus, Ewha Womans 9.00 am – 9.15 am University) and Euston Quah (Head of Division, Nanyang Technological University and President, Economic Society of Singapore) Speech by Guest-of-Honour 9.15 am – 9.25 am Guest-of-Honour: Ambassador Lam Chuan Leong (Chairman, Competition Commission of Singapore) Keynote Address I: The Trinity Growth Theory 9.25 am – 10.00 am Speaker: Lim Chong Yah (Nanyang Technological University) Chair: Chew Soon Beng (Nanyang Technological University) Coffee Break 10.00 am – 10.30 am Venue: Galleria Foyer (Level 3) Concurrent Session 1: CS1A to CS1G 10.30 am – 12.30 pm Venues: Oriole, Canary I, Canary II, Bluebird, Nightingale, Hummingbird, Sharma (Level 4) Lunch Break 12.30 pm – 2.00 pm Venue: Lyrebird (Level 3) Concurrent Session 2: CS2A to CS2H 2.00 pm – 4.00 pm Venues: Oriole, Canary I, Canary II, Bluebird, Nightingale, Hummingbird, Sharma (Level 4), Galleria Ballroom (Level 3) Coffee Break 4.00 pm – 4.30 pm Venue: Level 4 Foyer Concurrent Session 3: CS3A to CS3G 4.30 pm – 6.00 pm Venues: Oriole, Canary I, Canary II, Bluebird, Nightingale, Hummingbird, Sharma (Level 4) ERIA Dinner Speakers: Fukunari Kimura (Chief Economist, ERIA) and 7.00 pm – 9.00 pm Ponciano S. Intal Jr. (Senior Researcher, ERIA) Venue: Riverfront -

Summary of Departmental Strengths Lingnan University

Summary of Departmental Strengths Lingnan University Faculty of Arts Department of Chinese 蔡宗齊教授為嶺南大學中文系講座教授,兼任美國伊利諾大學香檳校區中國 文學和比較文學教授,是享有國際聲譽的著名學者。蔡教授主持《嶺南學報》 復刊工作,致力於復興廣州嶺南大學輝煌的國學傳統,提升本系學術研究水 準,使嶺大中文系的聲譽更上一個臺階。 本系在古典經學、語言學和文學方面有李雄溪教授、許子濱教授、劉燕萍教 授、汪春泓教授等,研究成果迭出。本系許子東教授則為資深的中國現當代 文學研究專家。 本系榮休教授劉紹銘、榮譽教授陳炳良、馬幼垣教授都是國際著名的學者。 他們退休後,仍繼續關注和提攜中文系的學術發展。2008 至 2012 年期間, 嶺大中文系獲香港賽馬會資助,設立“傑出現代文學訪問教授計劃”,獲邀請 的學者包括復旦大學陳思和教授、顧彬教授、王曉明教授、劉再復教授和鍾 玲教授等。另一方面,本系自 2003 年起亦設立駐校作家計劃,曾邀請白先 勇、馬原、王安憶、阿城、李昂、張大春、蘇童等作家到本系任教。這兩項 計劃均對本系的研究生課程有直接的幫助。 在嶺大中文系畢業的研究生,不少已有卓越的文學和學術成就,如上海作家 須蘭,是《投名狀》的主要編劇;香港作家陳慧,代表作《拾香記》獲香港 中文文學雙年獎。 Department of Cultural Studies Established in 2000, the Department of Cultural Studies is the first department of its kind in Asia, with a fully interdisciplinary and cosmopolitan faculty committed exclusively to teaching and research in contemporary Cultural Studies. For our post-graduate students, we provide close-contact supervision and working relationships with world-class scholars. Students can avail of travel grants to participate in conferences worldwide. We also offer various opportunities for 1 exposure to workshops in different locations through our Inter-Asia cultural studies networks. Department of English Contemporary English Studies is one exciting area of teaching and research. The Department of English offers a Honours Degree programme and a postgraduate programme in English Studies. For us, English Studies embraces the study of Contemporary Literature in English, Applied Linguistic Studies and Language Studies. We recognise English -

Asia Pacific Region AP Newsletter No

Asia Pacific Region AP Newsletter No. 30 Nov. 2006 Official Newsletter of ComSoc Asia Pacific Board www.comsoc.org/~apb Asia-Pacific Region Officers (2006 – 2007) Information Services Committee Director Chair: Song Chong (KAIST) Daehyoung Hong (Sogang University) Homepage Vice Chair: Joonhyuk Kang (ICU) Vice Director Newsletter Qian Zhang (Hong Kong University of Zhisheng Niu (Tsinghua University) Vice Chair: Science & Technology) Naoaki Yamanaka (Keio University) Secretary: Jeonghoon Mo (ICU) Secretary Membership Development Committee Jinwoo Choe (Sogang University) Chair: Wanjiun Liao (National Twaiwan University) Lin Zhang, Forest (Tsinghua University) Vice Chair: Miki Yamamoto (Kansai University) Seungkeun Park (ETRI, PEC) Treasurer Secretary: Jie Li (University of Tsukuba) Young Yong Kim (Yonsei University) Chapters Coordination Committee Special Liaison for ComSoc Activities Chair: Abbas Jamalipour (Univeristy of Won-Ki Hong, James Sydney) Vice Chair: Kwang Bok Lee (Seoul National Technical Affair Committee University) Chair: Seung-Woo Seo (Seoul National Secretary: Debashis Saha (Indian Institute of University) Management (IIM) Calcutta) Vice Chair: Takaya Yamazato (Nagoya University) Guangbin Fan (Intel China Research AP Advisors Center) Byeong Gi Lee (Seoul National University) Bin Qiu (Monash University) Desmond Taylor (University of Canterbury) Secretary: Jae-Hyun Kim (Ajou Univeristy) Iwao Sasase (Keio University) Kwang-Cheng Chen (National Taiwan Meeting & Conference Committee University) Chair: Tomoaki Ohtsuki (Keio University) Lin-Shan Lee (Academia Sinica, National Vice Chair: Jin Seek Choi (Hanyang University) Taiwan University) Secretary: Kohei Shimoto (NTT Network Service Naohisa Ohta (Keio University) Systems Labs) Noriyoshi Kuroyanagi (Chubu University) Tomonori Aoyama (The University of Tokyo) T.T. Tjhung (Institute for InfoComm Research) 1 Contents I. Hot Topics I.1 ICC 2006 APB Meeting Minutes I.2 ICC 2006 APB Meeting Attendee List I.3 Report on Student Travel Grant in AP Region I.4 Report on Distinguished Lecturer Tour (DLT) II. -

The University of Hong Kong

Updated on 5 December 2018 THE UNIVERSITY OF HONG KONG HKU Strategic Partnerships Fund with University of Toronto (UToronto), University of Chicago (UChicago), University College London (UCL), King’s College London (KCL), University of Sydney (USyd) and Tsinghua University (Tsinghua) 2018-2019 I am pleased to announce the third annual cycle of the HKU Strategic Partnerships Fund with five top universities around the world, namely University of Toronto (UToronto), University of Chicago (UChicago), University College London (UCL), King’s College London (KCL) and University of Sydney (USyd), as well as the first cycle of the joint funding with Tsinghua University (Tsinghua). Applications are now invited from eligible members of the University. Background Our aspiration to become the “Asia’s Global University” is an explicit goal set out in the document “Asia’s Global University, HKU: the next decade, our vision for 2016-2025” under the vision of [3+1] I’s, viz. Innovation, Interdisciplinarity & Internationalisation converging to create Impact. The global higher education sector is increasingly competitive and rapidly changing. Our Mainland and international efforts have resulted in positive outcomes in student and staff recruitment and demographics, research collaborations, teaching, and knowledge exchange. We must sustain our current activities. Opportunities exist to strategically reposition HKU by taking full advantage of our unique attributes, assets, networks, and talent pools. HKU is well situated in a dynamic region of Asia and embodies a tradition that exemplifies the core value and best practices of the international academic community. Strategic partnership has emerged as an effective means to better position top world universities within the global knowledge node to deliver greater societal impact and secure greater visibility and recognition.