Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Glide Suppression': Consentius, 27.17–20 N

Some neglected evidence on Vulgar Latin ‘glide suppression’: Consentius, 27.17‒20 N.* By JULIA BURGHINI, Córdoba (Argentina) / JAVIER URÍA, Zaragoza Both i and u played an important role in the phonetic evolution of many Latin words. The complexity of that evolution is related to the ambiguous phonetic nature of those phonemes, which from the time of ancient grammarians are recognised to have the capacity of acting as either a vowel or a consonant.1 This double capacity is particularly relevant in contexts where either of them is followed by another vowel forming a hiatus, for the possibility arises of either preserving the hiatus (this is the regular solution of standard Latin: ui.ti.um)2 or grouping the two vowels into the same syllable (this is the most common solution in substandard Latin: ui.tjum).3 However, evidence from both classical metre and inscriptions shows that there are two further possible ways of pronouncing those sequences, namely uit.jum (as seen in Vergil’s [Aen. 2.16] ab.ie.te)4 and ui.t(i)um (with loss of i, u). It is mainly the latter (for convenience we will refer to it as ‘glide __________ * This paper has benefitted from a grant from the Spanish “Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología” (Project FFI2011‒30203‒C02‒02). Thanks are due to O. Álvarez Huerta, J.-L. Moralejo, and R. Maltby for commenting on previous drafts of this paper. 1 See e.g. Char. gramm. 5.4‒5 B. harum duae, i et u, transeunt in consonantium potestatem, cum aut ipsae inter se geminantur aut cum aliis uocalibus iunguntur, ut Iuno uita et Ianus iecor uates uelox uox. -

The POSTDATA Network of Ontologies for European Poetry

The POSTDATA network of Ontologies for European Poetry. María Luisa Diez Platasa , Salvador Rosa*, Elena González-Blancob, Helena Bermúdezc, Oscar Corchod, Javier de la Rosaa, Alvaro Pérez a POSTADATA Project. SSCC. Escuela Técnica Superior de Informática, UNED, Madrid, Spain b Coverwallet. Madrid, Spain c Section des Sciences du Langage et de l’Information, Université de Lausanne, Suisse d OntoloGy EnGineerinG Group. Facultad de Informática, Universidad Politécnica, Madrid Abstract. One of the lines of work in Digital Humanities is concerned with standardization processes to describe traditional concepts using computer-readable languages. In regard to Literary studies, poetry is a particularly complex domain due to, among other aspects, the special use of language that it implies. This paper presents a network of ontologies for capturing the poetry domain knowledge. The most significative ontologies are presented. These ontologies are related to the poetic work, and its structural and prosodic components. A date ontology that represents the especial needs of literary works is presented as well. This work is part of the results of the POSTDATA ERC (Poetry Standardization and Linked Open Data) project, which aims to provide a means for poetry researchers to publish their semantically enriched data as Linked Open Data (LOD), in the context of European poetry. Keywords: European Poetry, Standardization, Network of Ontologies, Interoperability, Linked Open Data 1. Introduction of theories is even bigger when comparing poetry schools from different languages and periods. One of The need for standardization has increased signifi- the most significant conceptual and terminological cantly in different research fields as a standard way of problems is that, even when a set of poetic works is understanding and exchanging information. -

Ancient Rhetorics and Language Difference. (2012) Directed by Dr

RAY, BRIAN, Ph.D. Toward a Translingual Composition: Ancient Rhetorics and Language Difference. (2012) Directed by Dr. Nancy A. Myers. 226 pp. The purpose of this dissertation is to outline a pedagogy that promotes language difference in college composition classrooms. Scholarship on language difference has strived for decades to transform teaching practices in mainstream, developmental, and second-language writing instruction. Despite compelling arguments in support of linguistic diversity, a majority of secondary and postsecondary writing teachers in the U.S. still privilege Standard English. However, non-native speakers of English now outnumber native speakers worldwide, a fact which promises to redefine what “standard” means from a translingual perspective. It is becoming clearer that multilingual writers, versed in flexible hermeneutic strategies and able to draw on a variety of Englishes and languages to make meaning, have significant advantages over monolingual students. My dissertation anticipates the pedagogical and programmatic changes necessitated by this global language shift. To this end, I join a number of scholars in arguing for a revival of classical style and the progymnasmata, albeit with the unique agenda of strengthening pedagogies of language difference. Although adapting classical rhetorics to promote translingual practices such as code-meshing at first seems to contradict the spirit of language difference given the dominant perception of Greco-Roman culture as imperialistic and intolerant of diversity, I reread neglected rhetoricians such as Quintilian in order to recover their latent multilingual potential. TOWARD A TRANSLINGUAL COMPOSITION: ANCIENT RHETORICS AND LANGUAGE DIFFERENCE by Brian Ray A Dissertation Submitted to The Faculty of the Graduate School at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Greensboro 2012 Approved by Nancy A. -

A Dictionary of Linguistics

MID-CENTURY REFERENCE LIBRARY DAGOBERT D. RUNES, Ph.D., General Editor AVAILABLE Dictionary of Ancient History Dictionary of the Arts Dictionary of European History Dictionary of Foreign Words and Phrases Dictionary of Linguistics Dictionary of Mysticism Dictionary of Mythology Dictionary of Philosophy Dictionary of Psychoanalysis Dictionary of Science and Technology Dictionary of Sociology Dictionary of Word Origins Dictionary of World Literature Encyclopedia of Aberrations Encyclopedia of the Arts Encyclopedia of Atomic Energy Encyclopedia of Criminology Encyclopedia of Literature Encyclopedia of Psychology Encyclopedia of Religion Encyclopedia of Substitutes and Synthetics Encyclopedia of Vocational Guidance Illustrated Technical Dictionary Labor Dictionary Liberal Arts Dictionary Military and Naval Dictionary New Dictionary of American History New Dictionary of Psychology Protestant Dictionary Slavonic Encyclopedia Theatre Dictionary Tobacco Dictionary FORTHCOMING Beethoven Encyclopedia Dictionary of American Folklore Dictionary of American Grammar and Usage Dictionary of American Literature Dictionary of American Maxims Dictionary of American Proverbs Dictionary of American Superstitions Dictionary of American Synonyms Dictionary of Anthropology Dictionary of Arts and Crafts Dictionary of Asiatic History Dictionary of Astronomy Dictionary of Child Guidance Dictionary of Christian Antiquity Dictionary of Discoveries and Inventions Dictionary of Etiquette Dictionary of Forgotten Words Dictionary of French Literature Dictionary of Geography -

THE BRETON of the CANTON of BRIEG 11 December

THE BRETON OF THE CANTON OF BRIEC1 PIERRE NOYER A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Celtic Studies Program Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of Sydney 2019 1 Which will be referred to as BCB throughout this thesis. CONCISE TABLE OF CONTENTS DETAILED TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................ 3 DEDICATION ............................................................................................................................... 21 ABBREVIATIONS USED IN THIS WORK ................................................................................. 24 1. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 29 2. PHONOLOGY ........................................................................................................................... 65 3. MORPHOPHONOLOGY ......................................................................................................... 115 4. MORPHOLOGY ....................................................................................................................... 146 5. SYNTAX .................................................................................................................................... 241 6. LEXICON.................................................................................................................................. 254 7. CONCLUSION......................................................................................................................... -

Phonological Effects and Functions of English Loan-Words on the Tiv

African Social Science and Humanities Journal (ASSHJ) https://journals.jfppublishers.com/asshj Research Article This article is published by JFP Phonological Effects and Functions of English Publishers in the African Social Loan-words on the Tiv Grammar Science and Humanities Journal (ASSHJ). Volume 2, Issue 1, 2021. Terfa Aor1* ISSN: 2709-1309 (Print) 1Department of Nigerian Languages, National Institute for Nigerian Languages, Aba Abia State, Nigeria, [email protected] 2709-1317 (Online) This article is distributed under a *Corresponding author Creative Common Attribution (CC BY-SA 4.0) International License. Abstract: There is no human language that is devoid of borrowing loan- words from a parent language to its own (recipient) language. When loan- Article detail words are injected into a recipient language, there are certain phonological effects that such words have on the grammar of such a language. This paper Published: 26 March 2021 critically discusses the phonological implications and functions of English Conflict of Interest: The author/s loan-words on Tiv the grammar. The objectives of this paper are to: classify declared no conflict of interest. phonological implications of English loan-words on the grammar of Tiv language; discuss the implications of English loan-words on Tiv grammar; explore the phonological functions of English loan-words; and, state reasons that necessitate borrowing of loan-words. The author used primary and secondary sources. The researcher used participant-observer technique as his primary source and documentary sources were used. It has been found out that most English loan-words have no substitutes in Tiv; loan-words have expanded the vocabulary of the Tiv grammar; the original syllabic structure of most loan-words changed from close to open syllables; and epenthetic letters are added to break consonant clusters, for plurality and as a hiatus repairing strategy. -

The Invention of Rhythm

The Invention of Rhythm by Darrell Smith Department of English Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Julianne Werlin, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Maureen Quilligan, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Joseph Donahue ___________________________ Fred Moten Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English in the Graduate School of Duke University 2016 i v ABSTRACT The Invention of Rhythm by Darrell Smith Department of English Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Julianne Werlin, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Maureen Quilligan, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Joseph Donahue ___________________________ Fred Moten An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English in the Graduate School of Duke University 2016 Copyright by Darrell Smith 2016 Abstract “The Invention of Rhythm” dismantles the foundational myth of modern English verse. It considers its two protagonists, Thomas Wyatt and Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, who together brought English poetry out of the middle ages: the latter taking the former’s experiments with Romance language verse forms and smoothing them into the first sustained examples of the iambic measures that would so strongly influence the Elizabethans, and in turn dominate English poetry until the coming of Modernism in the twentieth century. It considers their contrastively-oscillating critical reputations from the seventeenth century to the present day, focusing on how historically-contingent aesthetic and socio-political values have been continuously brought to bear on studies of their respective versification, in fact producing, and perpetuating the mythological narrative, with negligable study of the linguistic and rhythmical patterns of their poems themselves. -

The Practice and Benefit of Applying Digital Markup In

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2015 The Practice and Benefit of Applying Digital Markup in Preserving Texts and Creating Digital Editions: A Poetical Analysis of a Blank- Verse Translation of Virgil's Aeneid William Dorner University of Central Florida Part of the Classical Literature and Philology Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Doctoral Dissertation (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Dorner, William, "The Practice and Benefit of Applying Digital Markup in Preserving Texts and Creating Digital Editions: A Poetical Analysis of a Blank-Verse Translation of Virgil's Aeneid" (2015). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 1421. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/1421 THE PRACTICE AND BENEFIT OF APPLYING DIGITAL MARKUP IN PRESERVING TEXTS AND CREATING DIGITAL EDITIONS: A POETICAL ANALYSIS OF A BLANK-VERSE TRANSLATION OF VIRGIL'S AENEID by WILLIAM DORNER M.A., Rhetoric and Composition, University of Central Florida, 2010 B.A., Creative Writing, University of Central Florida, 2007 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Texts and Technology in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2015 Major Professor: Mark L. Kamrath © 2015 William Dorner ii ABSTRACT Numerous examples of the “digital scholarly edition” exist online, and the genre is thriving in terms of interdisciplinary interest as well as support granted by funding agencies. -

The Practice and Benefit of Applying Digital Markup In

THE PRACTICE AND BENEFIT OF APPLYING DIGITAL MARKUP IN PRESERVING TEXTS AND CREATING DIGITAL EDITIONS: A POETICAL ANALYSIS OF A BLANK-VERSE TRANSLATION OF VIRGIL'S AENEID by WILLIAM DORNER M.A., Rhetoric and Composition, University of Central Florida, 2010 B.A., Creative Writing, University of Central Florida, 2007 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Texts and Technology in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2015 Major Professor: Mark L. Kamrath © 2015 William Dorner ii ABSTRACT Numerous examples of the “digital scholarly edition” exist online, and the genre is thriving in terms of interdisciplinary interest as well as support granted by funding agencies. Some editions are dedicated to the collection and representation of the life’s work of a single author, others to mass digitization and preservation of centuries’ worth of texts. Very few of these examples, however, approach the task of in-text interpretation through visualization. This project describes an approach to digital representation and investigates its potential benefit to scholars of various disciplines. It presents both a digital edition as well as a framework of justification surrounding said edition. In addition to composing this document as an XML file, I have digitized a 1794 English translation of Virgil’s Aeneid and used a customized digital markup schema based on the guidelines set forth by the Text Encoding Initiative to indicate a set of poetic figures—such as simile and alliteration—within that text for analysis. While neither a translation project nor strictly a poetical analysis, this project and its unique approach to interpretive representation could prove of interest to scholars in several disciplines, including classics, digital scholarship, information management, and literary theory. -

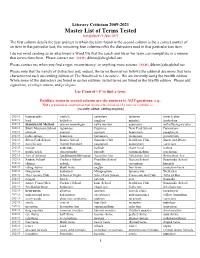

Master List of Terms Tested Last Updated 11 June 2021

Literary Criticism 2009-2021 Master List of Terms Tested last updated 11 June 2021 The first column details the year and test in which the term found in the second column is the a correct answer of an item in that particular test; the remaining four columns offer the distractors used in that particular test item. I do not mind sending as an attachment a Word file that the coach and his or her team can manipulate in a manner that serves them best. Please contact me: (NEW) [email protected] Please contact me when you find a typo, inconsistency, or anything more serious: (NEW) [email protected] Please note that the variety of distractors and, indeed, the terms themselves follows the editorial decisions that have characterized each succeeding edition of The Handbook to Literature. We are currently using the twelfth edition. While some of the distractors are found in earlier editions, tested terms are found in the twelfth edition. Please add sigmatism, envelope stanza, and prolepsis. Use Control + F to find a term. Boldface terms in second column are the answers to NOT questions; e.g., Not a grammatical construction that involves the omission of a letter or a syllable is . [recently edited; editing ongoing] 2021 S hagiography canticle epistolary lampoon miracle play 2021 S bard balladeer jongleur minstrel troubadour 2021 S Stanislavski Method interior monologue naïve narrator panoramic self-effacing narrator 2021 S Black Mountain School Agrarians Fugitives New York School Parnassians 2021 S allonym ananym eponym heteronym pseudonym 2021 -

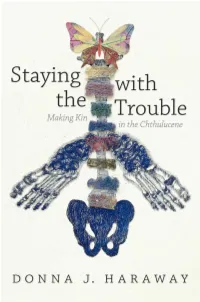

Making Kin in the Chthulucene Donna J

Staying with the Trouble Experimental Futures: Technological lives, scientific arts, anthropological voices A series edited by Michael M. J. Fischer and Joseph Dumit Staying with the Trouble Making Kin in the Chthulucene Donna J. Haraway duke university press durham and london 2016 © 2016 Duke University Press Chapter 1 appeared as “Jeux de ficelles avecs All rights reserved des espèces compagnes: Rester avec le trou- Printed in the United States of America ble,” in Les animaux: deux ou trois choses que on acid-free paper ∞ nous savons d’eux, ed. Vinciane Despret and Designed by Amy Ruth Buchanan Raphaël Larrère (Paris: Hermann, 2014), Typeset in Chaparral Pro by Copperline 23–59. © Éditions Hermann. Translated by Vinciane Despret. Library of Congress Cataloging-in- Chapter 4 is lightly revised from “Anthropo- Publication Data. Names: Haraway, cene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chthu- Donna Jeanne, author. Title: Staying lucene: Making Kin,” which was originally with the trouble : making kin in the published in Environmental Humanities, vol. 6, Chthulucene / Donna J. Haraway. under Creative Commons license cc by-nc-nd Description: Durham : Duke University 3.0. © Donna Haraway. Press, 2016. | Series: Experimental futures: technological lives, scientific Chapter 5 is reprinted from wsq: Women’s arts, anthropological voices | Includes Studies Quarterly 40, nos. 3/4 (spring/sum- bibliographical references and index. | mer 2012): 301–16. Copyright © 2012 by the Description based on print version re- Feminist Press at the City University of New cord and cip data provided by publisher; York. Used by permission of The Permissions resource not viewed. Identifiers: lccn Company, Inc., on behalf of the publishers, 2016019477 (print) | lccn 2016018395 feministpress.org. -

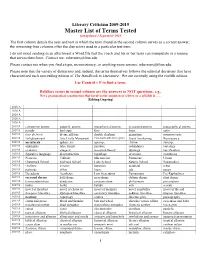

Master List of Terms Tested Last Updated 1 September 2019

Literary Criticism 2009-2019 Master List of Terms Tested last updated 1 September 2019 The first column details the year and test in which the term found in the second column serves as a correct answer; the remaining four columns offer the distractors used in a particular test item. I do not mind sending as an attachment a Word file that the coach and his or her team can manipulate in a manner that serves them best. Contact me: [email protected] Please contact me when you find a typo, inconsistency, or anything more serious: [email protected] Please note that the variety of distractors and, indeed, the terms themselves follows the editorial decisions that have characterized each succeeding edition of The Handbook to Literature. We are currently using the twelfth edition. Use Control + F to find a term. Boldface terms in second column are the answers to NOT questions; e.g., Not a grammatical construction that involves the omission of a litter or a syllable is . [Editing Ongoing] 2020 A 2020 A 2020 A 2020 A 2020 A 2019 S companion poems autotelic poems metaphysical poems occasional poems topographical poems 2019 S parody burlesque farce hoax satire 2019 S tour de force divine afflatus double elephant gigantism magnum opus 2019 S Enlightenment Arts Crafts Movement Commonwealth Interregnum Great Awakening Renaissance 2019 S metathesis aphaeresis apocope elision syncope 2019 S ambiguity false friend paradox redundancy tautology 2019 S scansion exegesis reception theory typology versification 2019 S figurative language deconstruction hypallage