DRAFT for PUBLIC COMMENT ANALYSIS of IMPEDIMENTS to FAIR HOUSING CHOICE WASHINGTON, D.C. DC Department of Housing and Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROUTES LINE NAME Sunday Supplemental Service Note 1A,B Wilson Blvd-Vienna Sunday 1C Fair Oaks-Fairfax Blvd Sunday 2A Washington

Sunday Supplemental ROUTES LINE NAME Note Service 1A,B Wilson Blvd-Vienna Sunday 1C Fair Oaks-Fairfax Blvd Sunday 2A Washington Blvd-Dunn Loring Sunday 2B Fair Oaks-Jermantown Rd Sunday 3A Annandale Rd Sunday 3T Pimmit Hills No Service 3Y Lee Highway-Farragut Square No Service 4A,B Pershing Drive-Arlington Boulevard Sunday 5A DC-Dulles Sunday 7A,F,Y Lincolnia-North Fairlington Sunday 7C,P Park Center-Pentagon No Service 7M Mark Center-Pentagon Weekday 7W Lincolnia-Pentagon No Service 8S,W,Z Foxchase-Seminary Valley No Service 10A,E,N Alexandria-Pentagon Sunday 10B Hunting Point-Ballston Sunday 11Y Mt Vernon Express No Service 15K Chain Bridge Road No Service 16A,C,E Columbia Pike Sunday 16G,H Columbia Pike-Pentagon City Sunday 16L Annandale-Skyline City-Pentagon No Service 16Y Columbia Pike-Farragut Square No Service 17B,M Kings Park No Service 17G,H,K,L Kings Park Express Saturday Supplemental 17G only 18G,H,J Orange Hunt No Service 18P Burke Centre Weekday 21A,D Landmark-Bren Mar Pk-Pentagon No Service 22A,C,F Barcroft-South Fairlington Sunday 23A,B,T McLean-Crystal City Sunday 25B Landmark-Ballston Sunday 26A Annandale-East Falls Church No Service 28A Leesburg Pike Sunday 28F,G Skyline City No Service 29C,G Annandale No Service 29K,N Alexandria-Fairfax Sunday 29W Braeburn Dr-Pentagon Express No Service 30N,30S Friendship Hghts-Southeast Sunday 31,33 Wisconsin Avenue Sunday 32,34,36 Pennsylvania Avenue Sunday 37 Wisconsin Avenue Limited No Service 38B Ballston-Farragut Square Sunday 39 Pennsylvania Avenue Limited No Service 42,43 Mount -

Washington, Dc International Business Guide

WASHINGTON, DC INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS GUIDE Contents 1 Welcome Letter — Mayor Muriel Bowser 3 Introduction 5 Why Washington, DC? 6 A Powerful Economy Infographic 8 Awards and Recognition 9 Washington, DC — Demographics 11 Washington, DC — Economy 12 Federal Government 12 Retail and Federal Contractors Real Estate and Construction 13 12 Professional and Business Services 13 Higher Education and Healthcare 12 Technology and Innovation 13 Creative Economy 12 Hospitality and Tourism 15 Washington, DC — An Obvious Choice For International Companies 16 The District — Map 19 Washington, DC — Wards 25 Establishing A Business in Washington, DC 25 Business Registration 27 Office Space 27 Permits And Licenses 27 Business And Professional Services 27 Finding Talent 27 Small Business Services 27 Taxes 27 Employment-related Visas 29 Business Resources 31 Business Incentives and Assistance 32 DC Government by the Letter / Acknowledgements D C C H A M B E R O F C O M M E R C E Dear Investor, Washington, DC, is a thriving, global marketplace. Over the past decade, we have experienced significant growth and transformation. The District of Columbia has one of the most educated workforces in the country, stable economic growth, an established research community, and a business-friendly government. I am proud to present you with the Washington, DC International Business Guide. This book contains relevant information for foreign firms interested in establishing a presence in our nation’s capital. In these pages, you will find background on our strongest business sectors, economic indicators, and foreign direct investment trends. In addition, there are a number of suggested steps as you consider bringing your business to DC. -

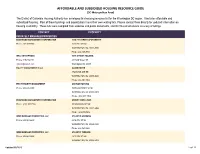

AFFORDABLE and SUBSIDIZED HOUSING RESOURCE GUIDE (DC Metropolitan Area)

AFFORDABLE AND SUBSIDIZED HOUSING RESOURCE GUIDE (DC Metropolitan Area) The District of Columbia Housing Authority has developed this housing resource list for the Washington DC region. It includes affordable and subsidized housing. Most of these buildings and organizations have their own waiting lists. Please contact them directly for updated information on housing availability. These lists were compiled from websites and public documents, and DCHA cannot ensure accuracy of listings. CONTACT PROPERTY PRIVATELY MANAGED PROPERTIES EDGEWOOD MANAGEMENT CORPORATION 1330 7TH STREET APARTMENTS Phone: 202-387-7558 1330 7TH ST NW WASHINGTON, DC 20001-3565 Phone: 202-387-7558 WEIL ENTERPRISES 54TH STREET HOUSING Phone: 919-734-1111 431 54th Street, SE [email protected] Washington, DC 20019 EQUITY MANAGEMENT II, LLC ALLEN HOUSE 3760 MINN AVE NE WASHINGTON, DC 20019-2600 Phone: 202-397-1862 FIRST PRIORITY MANAGEMENT ANCHOR HOUSING Phone: 202-635-5900 1609 LAWRENCE ST NE WASHINGTON, DC 20018-3802 Phone: (202) 635-5969 EDGEWOOD MANAGEMENT CORPORATION ASBURY DWELLINGS Phone: (202) 745-7334 1616 MARION ST NW WASHINGTON, DC 20001-3468 Phone: (202)745-7434 WINN MANAGED PROPERTIES, LLC ATLANTIC GARDENS Phone: 202-561-8600 4216 4TH ST SE WASHINGTON, DC 20032-3325 Phone: 202-561-8600 WINN MANAGED PROPERTIES, LLC ATLANTIC TERRACE Phone: 202-561-8600 4319 19th ST S.E. WASHINGTON, DC 20032-3203 Updated 07/2013 1 of 17 AFFORDABLE AND SUBSIDIZED HOUSING RESOURCE GUIDE (DC Metropolitan Area) CONTACT PROPERTY Phone: 202-561-8600 HORNING BROTHERS AZEEZE BATES (Central -

District Columbia

PUBLIC EDUCATION FACILITIES MASTER PLAN for the Appendices B - I DISTRICT of COLUMBIA AYERS SAINT GROSS ARCHITECTS + PLANNERS | FIELDNG NAIR INTERNATIONAL TABLE OF CONTENTS APPENDIX A: School Listing (See Master Plan) APPENDIX B: DCPS and Charter Schools Listing By Neighborhood Cluster ..................................... 1 APPENDIX C: Complete Enrollment, Capacity and Utilization Study ............................................... 7 APPENDIX D: Complete Population and Enrollment Forecast Study ............................................... 29 APPENDIX E: Demographic Analysis ................................................................................................ 51 APPENDIX F: Cluster Demographic Summary .................................................................................. 63 APPENDIX G: Complete Facility Condition, Quality and Efficacy Study ............................................ 157 APPENDIX H: DCPS Educational Facilities Effectiveness Instrument (EFEI) ...................................... 195 APPENDIX I: Neighborhood Attendance Participation .................................................................... 311 Cover Photograph: Capital City Public Charter School by Drew Angerer APPENDIX B: DCPS AND CHARTER SCHOOLS LISTING BY NEIGHBORHOOD CLUSTER Cluster Cluster Name DCPS Schools PCS Schools Number • Oyster-Adams Bilingual School (Adams) Kalorama Heights, Adams (Lower) 1 • Education Strengthens Families (Esf) PCS Morgan, Lanier Heights • H.D. Cooke Elementary School • Marie Reed Elementary School -

Ward 7 Heritage Guide

WARD 7 HERITAGE GUIDE A Discussion of Ward 7 Cultural and Heritage Resources Ward 7 Heritage Guide Text by Patsy M. Fletcher, DC Historic Preservation Office Design by Kim Elliott, DC Historic Preservation Office Published 2013 Unless stated otherwise, photographs and images are from the DC Office of Planning collection. This project has been funded in part by U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service Historic Preservation Fund grant funds, administered by the District of Columbia’s Historic Preservation Office. The contents and opinions contained in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the U.S. Depart- ment of the Interior, nor does the mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation by the U.S. Department of the Interior. This program has received Federal financial assistance for the identification, protection, and/or rehabilitation of historic properties and cultural resources in the District of Columbia. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, the U.S. Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, or disability in its Federally assisted programs. If you believe that you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility as described above, or if you desire further information, please write to: Office of Equal Opportunity, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1849 C Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20240. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction......................................................................................................................5 -

Far Northeast and Southeast Area Element

AREA ELEMENTS Chapter 17 Far Northeast & Southeast Area Element Gateway AREA ELEMENTS Arboretum Kenilworth Trinidad Eastland Deanwood EASTERN AVENUE Gardens Deanwood Carver Langston Mayfair CAPITOL HILL Burrville Central NE Minnesota Ave Lincoln Heights Kingman Park Fort Mahan NE Boundary River Park Terrace Benning Grant Park Capitol View Benning Road Fort Chaplin Park Capitol Heights Lincoln Fort Dupont Park Marshall Hill Greenway Heights East Benning Ridge Fort Dupont Park LOWER ANACOSTIA Twining WATERFRONT/ NORTHEAST FAR SOUTHEAST AND CHAPTER 17: NEAR SOUTHWEST Dupont Park Randle Fairlawn Penn Branch Highlands SOUTHERN AVENUE Fairfax Village Historic Anacostia NAYLOR ROAD Hillcrest Skyland Naylor Hillsdale Gardens FAR SOUTHEAST Knox Hill/ AND SOUTHWEST Buena Vista Gateway AREA ELEMENTS AREA ELEMENTS Arboretum Far Northeast & Southeast Area Element Kenilworth Trinidad Overview 1700 Eastland Deanwood EASTERN AVENUE he Far Northeast and Southeast Planning Area encompasses 17 Gardens Deanwood Tthe 8.3 square miles located east of I-295 and north of Naylor Road SE. Its Carver boundaries are shown in the Map at left. Most of this area has historically Langston Mayfair been Ward 7 although in past decades, parts have been included in Wards 6 and 8. 1700.1 CAPITOL HILL Burrville Far Northeast and Southeast is known for its stable, attractive Central NE Minnesota Ave Lincoln Heights neighborhoods and its diverse mix of housing. It includes single-family Kingman Park Fort communities like Hillcrest, Eastland Gardens, and Penn Branch; row house Mahan NE Boundary River Park and semi-detached housing neighborhoods such as Twining, River Terrace, Terrace Benning Grant Park and Fairlawn; and apartment communities like Naylor Gardens, Mayfair Mansions, and Lincoln Heights. -

The 2020 Transit Development Plan

DC Circulator Transit Development Plan 2020 Update April 12, 2021 (Page intentionally left blank) DC Circulator 2020 TDP i April 2021 Transit Development Plan 2020 Update DRAFT Table of Contents 1.046T 46T Introduction46T ..............................................................46T .................................................... 1 46T 46T Purpose of the Transit Development Plan (TDP)46T ..............................................................46T ............ 1 46T 46T Transit Development Plan Process46T ..............................................................46T ................................. 3 2.046T 46T DC Circulator System Overview46T ..............................................................46T ....................... 4 46T 46T History46T ..............................................................46T ............................................................................. 4 46T 46T Organizational Structure46T 46T ............................................................................................................... 6 46T 46T Strategic Goals and Objectives46T ..............................................................46T ....................................... 6 46T 46T Levels of Service46T 46T ............................................................................................................................ 8 46T 46T Fare Structure46T ..............................................................46T ............................................................... 10 46T 46T Fleet -

Line Name Routes Per Line Benning Road-H Street X2 DC Garfield

Routes per Line Name Line Jurisdicti on Benning Road-H Street X2 DC Garfield-Anacostia Loop W6,8 DC East Capitol Street-Cardozo 96,97 DC Connecticut Avenue L1,2 DC Brookland-Fort Lincoln H6 DC Crosstown H2,3,4 DC Fort Totten-Petworth 60,64 DC Benning Heights-Alabama Ave V7,8 DC Hospital Center D8 DC Glover Park-Dupont Circle D2 DC 14th Street 52,54 DC Sibley Hospital - Stadium-Armory D6 DC Ivy City-Franklin Square D4 DC Takoma-Petworth 62,63 DC Massachusetts Avenue N2,4,6 DC Military Road-Crosstown E4 DC Sheriff Road-River Terrace U4 DC Ivy City-Fort Totten E2 DC Mount Pleasant 42,43 DC North Capitol Street 80 DC P Street-LeDroit Park G2 DC Park Road-Brookland H8,9 DC Pennsylvania Avenue 32,34,36 DC Deanwood-Alabama Avenue W4 DC Wisconsin Avenue 31,33 DC Rhode Island Avenue G8 DC Georgia Avenue Limited 79 DC 16th Street S2,4 DC Friendship Heights-Southeast 30N,30S DC Georgia Avenue-7th Street 70 DC Convention Center-Southwest Waterfront 74 DC U Street-Garfield 90,92 DC Capitol Heights-Minnesota Ave V2,4 DC Deanwood-Minnesota Ave Sta U7 DC Mayfair-Marshall Heights U5,6 DC Bladensburg Road-Anacostia B2 DC United Medical Center-Anacostia W2,3 DC Anacostia-Eckington P6 DC Anacostia-Congress Heights A2,6,7,8 DC Anacostia-Fort Drum A4,W5 DC National Harbor-Southern Ave NH1 MD Annapolis Road T18 MD Greenbelt-Twinbrook C2,4 MD Bethesda-Silver Spring J1,2 MD National Harbor-Alexandria NH2 MD Chillum Road F1,2 MD District Heights-Seat Pleasant V14 MD Eastover-Addison Road P12 MD Forestville K12 MD Georgia Avenue-Maryland Y2,7,8 MD Marlboro Pike J12 MD Marlow Heights-Temple Hills H11,12,13 MD College Park 83,83X,86 MD New Hampshire Avenue-Maryland K6 MD Martin Luther King Jr. -

Creating and Sustaining Limited Equity Cooperatives in the District of Columbia

RESEARCH REPORT February 2020 Creating and Sustaining Limited Equity Cooperatives in the District of Columbia Authored By: Kathryn Howell, PhD Urban/Regional Studies and Planning Program, Virginia Commonwealth University Scott Bruton, PhD Coalition for Nonprofit Housing and Economic Development Anna Clemens, MURP Urban/Regional Studies and Planning Program, Virginia Commonwealth University Prepared By: Coalition for Nonprofit Housing and Economic Development Acknowledgements This report would not have been possible without the support of the resident-owners who took time to respond to surveys and participate in interviews and focus groups, which allowed the authors to understand the origins of their buildings and the opportunities and challenges of living in, owning, and managing Limited Equity Cooperatives (LECs) in the District of Columbia. In addition, the technical assistance providers, organizers, attorneys, District agency staff, and lenders who connected us to residents and shared their experiences working with LECs were critical to understanding the full process. Additionally, students in the Virginia Commonwealth University’s Masters of Urban and Regional Planning program’s Housing Policy course contributed to this study through conducting interviews and developing background research during the spring 2019 semester. Peter Tatian (Urban Institute) provided valuable feedback, which improved this report. The authors also would like to thank the following funders for their generous financial support, without which this study would -

State of Washington, D.C.'S Neighborhoods A-3

State of Washington, D.C.’s Neighborhoods Prepared by Peter A. Tatian G. Thomas Kingsley Margery Austin Turner Jennifer Comey Randy Rosso Prepared for The Office of Planning The Government of the District of Columbia September 30, 2008 The Urban Institute 2100 M Street, NW Washington, DC 20037 UI project no. 08040-000-01 State of Washington, D.C.’s Neighborhoods ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ............................................................................................... ii Acknowledgments............................................................................................. vi About this Report ............................................................................................... 1 I. Introduction...................................................................................................... 3 II. Demographics................................................................................................. 9 Population......................................................................................................................9 Households..................................................................................................................13 III. Economy – Jobs and Income ..................................................................... 15 Employed Residents and Unemployment Rate...........................................................15 Poverty and Household Income ..................................................................................18 Public Assistance -

Fort Dupont Park Historic Resources Study Final Robinson & Associates

Fort Dupont Park Historic Resources Study Final Robinson & Associates, Inc. November 1, 2004 Page 1 ______________________________________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS I. LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS 2 II. PURPOSE AND METHODOLOGY 5 III. SUMMARY OF SIGNIFICANCE 6 IV. HISTORIC CONTEXT STATEMENT 20 1. Pre-Civil War History 20 2. 1861-65: The Civil War and Construction of Fort Dupont 25 3. Post-Civil War Changes to Washington and its Forts 38 4. The Planning and Construction of the Fort Drive 48 5. Creation of Fort Dupont Park 75 6. 1933-42: The Civilian Conservation Corps Camp at Fort Dupont Park 103 7. 1942-45: Antiaircraft Artillery Command Positioned in Fort Dupont Park 116 8. History of the Golf Course 121 9. 1938 through the 1970s: Continued Development of Fort Dupont Park 131 10. Recreational, Cultural, and African-American Family Use of Fort Dupont Park 145 11. Proposals for the Fort Circle Parks 152 12. Description of Fort Dupont Park Landscape Characteristics, Buildings and Structures 155 V. BIBLIOGRAPHY 178 VI. KEY PARK LEGISLATION 191 Fort Dupont Park Historic Resources Study Final Robinson & Associates, Inc. November 1, 2004 Page 2 ______________________________________________________________________________________ I. LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1 Fort Dupont Park is located in the southeast quadrant of Washington, D.C. 7 Figure 2 Fort Dupont Park urban context, 1995 8 Figure 3 Map of current Fort Dupont Park resources 19 Figure 4 Detail of the 1856-59 Boschke Topographical Map 24 Figure 5 Detail -

Washington DC Neighborhodd Trends Report 2013/14

CAPITAL 2013 /14’ MARKET WASHINGTON DC APPRAISAL NEIGHBORHOOD RESEARCH TRENDS DESK REPORT VOLUME 1, MARCH 2014 When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir. —John Maynard Keynes Contents 4 Introduction 4 Conventional, Conforming 30-Yr Fixed-Rate 4 Mortgage-Related Bond Issuance and Outstanding 6 The DC Market: One/ Five/ Ten-Year Relative Returns 7 DC Index vs. 10-City Composite Component Indices 7 Seasonality Index 7 Months of Inventory 10 Total Sales Volume and Financing Trends 11 Median Days on Market (DOM) 11 Distressed Sales 13 Parking 13 Market Value and Sales Volume 16 Washington DC: Neighborhood Trends 2013 16 Sales Volume Leaders 16 Market Cap Leaders 19 Median Sale Price 21 Median Sale to List Price 22 Median Days on Market 23 Distressed Sales 24 Neighborhood Databook 2013 30 Neighborhood Map 31 About Us 32 End Notes / General Disclaimer 1 202 320 3702 [email protected] 1125 11 St NW 402 WDC 20001 www.CapitalMarketAppraisal.com Introduction Mortgage-Related Bond Issuance and Outstanding he Capital Market Appraisal 2013 Neighborhood Trends Over the prior year residential mortgage-related bond is- Report was developed to provide market participants suance3 declined 7.6%, falling from $2.019 trillion in 2012 to with a comprehensive overview of the residential real $1.866 trillion in 2013. Over the same period of time resi- T 1 3 estate market in Washington, DC (DC Market ). dential mortgage-related bonds outstanding declined 1.04% from $8.179 trillion in 2012 to $8.094 trillion in 2013. As the We begin by highlighting a few broad measure—medium term overwhelming majority of residential mortgages are packaged trends in the mortgage market.