How False Assumptions Still Haunt Theories of Consciousness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theoretical Models of Consciousness: a Scoping Review

brain sciences Review Theoretical Models of Consciousness: A Scoping Review Davide Sattin 1,2,*, Francesca Giulia Magnani 1, Laura Bartesaghi 1, Milena Caputo 1, Andrea Veronica Fittipaldo 3, Martina Cacciatore 1, Mario Picozzi 4 and Matilde Leonardi 1 1 Neurology, Public Health, Disability Unit—Scientific Department, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico Carlo Besta, 20133 Milan, Italy; [email protected] (F.G.M.); [email protected] (L.B.); [email protected] (M.C.); [email protected] (M.C.); [email protected] (M.L.) 2 Experimental Medicine and Medical Humanities-PhD Program, Biotechnology and Life Sciences Department and Center for Clinical Ethics, Insubria University, 21100 Varese, Italy 3 Oncology Department, Mario Negri Institute for Pharmacological Research IRCCS, 20156 Milan, Italy; veronicaandrea.fi[email protected] 4 Center for Clinical Ethics, Biotechnology and Life Sciences Department, Insubria University, 21100 Varese, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-02-2394-2709 Abstract: The amount of knowledge on human consciousness has created a multitude of viewpoints and it is difficult to compare and synthesize all the recent scientific perspectives. Indeed, there are many definitions of consciousness and multiple approaches to study the neural correlates of consciousness (NCC). Therefore, the main aim of this article is to collect data on the various theories of consciousness published between 2007–2017 and to synthesize them to provide a general overview of this topic. To describe each theory, we developed a thematic grid called the dimensional model, which qualitatively and quantitatively analyzes how each article, related to one specific theory, debates/analyzes a specific issue. -

Biocentrism in Environmental Ethics: Questions of Inherent Worth, Etiology, and Teleofunctional Interests David Lewis Rice III University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 8-2016 Biocentrism in Environmental Ethics: Questions of Inherent Worth, Etiology, and Teleofunctional Interests David Lewis Rice III University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Ethics and Political Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Rice, David Lewis III, "Biocentrism in Environmental Ethics: Questions of Inherent Worth, Etiology, and Teleofunctional Interests" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 1650. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/1650 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Biocentrism in Environmental Ethics: Questions of Inherent Worth, Etiology, and Teleofunctional Interests A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Philosophy by David Rice Delta State University Bachelor of Science in Biology, 1994 Delta State University Master of Science in Natural Sciences in Biology, 1999 University of Mississippi Master of Arts in Philosophy, 2009 August 2016 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. ____________________________________ Dr. Richard Lee Dissertation Director ____________________________________ ____________________________________ Dr. Warren Herold Dr. Tom Senor Committee Member Committee Member Abstract Some biocentrists argue that all living things have "inherent worth". Anything that has inherent worth has interests that provide a reason for why all moral agents should care about it in and of itself. There are, however, some difficulties for biocentric individualist arguments which claim that all living things have inherent worth. -

Just Deserts: the Dark Side of Moral Responsibility

(Un)just Deserts: The Dark Side of Moral Responsibility Gregg D. Caruso Corning Community College, SUNY What would be the consequence of embracing skepticism about free will and/or desert-based moral responsibility? What if we came to disbelieve in moral responsibility? What would this mean for our interpersonal re- lationships, society, morality, meaning, and the law? What would it do to our standing as human beings? Would it cause nihilism and despair as some maintain? Or perhaps increase anti-social behavior as some re- cent studies have suggested (Vohs and Schooler 2008; Baumeister, Masi- campo, and DeWall 2009)? Or would it rather have a humanizing effect on our practices and policies, freeing us from the negative effects of what Bruce Waller calls the “moral responsibility system” (2014, p. 4)? These questions are of profound pragmatic importance and should be of interest independent of the metaphysical debate over free will. As public procla- mations of skepticism continue to rise, and as the mass media continues to run headlines announcing free will and moral responsibility are illusions,1 we need to ask what effects this will have on the general public and what the responsibility is of professionals. In recent years a small industry has actually grown up around pre- cisely these questions. In the skeptical community, for example, a num- ber of different positions have been developed and advanced—including Saul Smilansky’s illusionism (2000), Thomas Nadelhoffer’s disillusionism (2011), Shaun Nichols’ anti-revolution (2007), and the optimistic skepti- cism of Derk Pereboom (2001, 2013a, 2013b), Bruce Waller (2011), Tam- ler Sommers (2005, 2007), and others. -

How Can We Solve the Meta-Problem of Consciousness?

How Can We Solve the Meta-Problem of Consciousness? David J. Chalmers I am grateful to the authors of the 39 commentaries on my article “The Meta-Problem of Consciousness”. I learned a great deal from reading them and from thinking about how to reply.1 The commentaries divide fairly nearly into about three groups. About half of them discuss po- tential solutions to the meta-problem. About a quarter of them discuss the question of whether in- tuitions about consciousness are universal, widespred, or culturally local. About a quarter discuss illusionism about consciousness and especially debunking arguments that move from a solution to the meta-problem to illusionism. Some commentaries fit into more than one group and some do not fit perfectly into any, but with some stretching this provides a natural way to divide them. As a result, I have divided my reply into three parts, each of which can stand alone. This first part is “How can We Solve the Meta-Problem of Conscousness?”. The other two parts are “Is the Hard Problem of Consciousness Universal?” and “Debunking Arguments for Illusionism about Consciousness”. How can we solve the meta-problem? As a reminder, the meta-problem is the problem of explaining our problem intuitions about consciousness, including the intuition that consciousness poses a hard problem and related explanatory and metaphysical intuitions, among others. One constraint is to explain the intuitions in topic-neutral terms (for example, physical, computational, structural, or evolutionary term) that do not make explicit appeal to consciousness in the explana- tion. In the target article, I canvassed about 15 potential solutions to the meta-problem. -

Metaphilosophy of Consciousness Studies

Part Three Metaphilosophy of Consciousness Studies Bloomsbury companion to the philosophy of consciousness.indb 185 24-08-2017 15:48:52 Bloomsbury companion to the philosophy of consciousness.indb 186 24-08-2017 15:48:52 11 Understanding Consciousness by Building It Michael Graziano and Taylor W. Webb 1 Introduction In this chapter we consider how to build a machine that has subjective awareness. The design is based on the recently proposed attention schema theory (Graziano 2013, 2014; Graziano and Kastner 2011; Graziano and Webb 2014; Kelly et al. 2014; Webb and Graziano 2015; Webb, Kean and Graziano 2016). This hypothetical building project serves as a way to introduce the theory in a step-by-step manner and contrast it with other brain-based theories of consciousness. At the same time, this chapter is more than a thought experiment. We suggest that the machine could actually be built and we encourage artificial intelligence experts to try. Figure 11.1 frames the challenge. The machine has eyes that take in visual input (an apple in this example) and pass information to a computer brain. Our task is to build the machine such that it has a subjective visual awareness of the apple in the same sense that humans describe subjective visual awareness. Exactly what is meant by subjective awareness is not a priori clear. Most people have an intuitive notion that is probably not easily put into words. One goal of this building project is to see if a clearer definition of subjective awareness emerges from the constrained process of trying to build it. -

1 Realism V Equilibrism About Philosophy* Daniel Stoljar, ANU 1

Realism v Equilibrism about Philosophy* Daniel Stoljar, ANU Abstract: According to the realist about philosophy, the goal of philosophy is to come to know the truth about philosophical questions; according to what Helen Beebee calls equilibrism, by contrast, the goal is rather to place one’s commitments in a coherent system. In this paper, I present a critique of equilibrism in the form Beebee defends it, paying particular attention to her suggestion that various meta-philosophical remarks made by David Lewis may be recruited to defend equilibrism. At the end of the paper, I point out that a realist about philosophy may also be a pluralist about philosophical culture, thus undermining one main motivation for equilibrism. 1. Realism about Philosophy What is the goal of philosophy? According to the realist, the goal is to come to know the truth about philosophical questions. Do we have free will? Are morality and rationality objective? Is consciousness a fundamental feature of the world? From a realist point of view, there are truths that answer these questions, and what we are trying to do in philosophy is to come to know these truths. Of course, nobody thinks it’s easy, or at least nobody should. Looking over the history of philosophy, some people (I won’t mention any names) seem to succumb to a kind of triumphalism. Perhaps a bit of logic or physics or psychology, or perhaps just a bit of clear thinking, is all you need to solve once and for all the problems philosophers are interested in. Whether those who apparently hold such views really do is a difficult question. -

A Response to Our Theatre Critics

J. Allan Hobson1 and Karl J. Friston2 A Response to Our Theatre Critics Abstract: We would like to thank Dolega and Dewhurst (2015) for a thought-provoking and informed deconstruction of our article, which we take as (qualified) applause from valued members of our audience. In brief, we fully concur with the theatre-free formulation offered by Dolega and Dewhurst and take the opportunity to explain why (and how) we used the Cartesian theatre metaphor. We do this by drawing an analogy between consciousness and evolution. This analogy is used to emphasize the circular causality inherent in the free energy prin- ciple (aka active inference). We conclude with a comment on the special forms of active inference that may be associated with self- awareness and how they may be especially informed by dream states. Keywords: consciousness; prediction; free energy; neuronal coding; Copyright (c) Imprint Academic 2016 inference; neuromodulation. For personal use only -- not for reproduction Introduction We enjoyed reading Dolega and Dewhurst’s (2015) critique of our earlier paper and thinking about the issues it raised. We begin our response by stating our position clearly — in terms of the few key Correspondence: Karl Friston, Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging, Institute of Neurology, Queen Square, London WC1N 3BG, UK. Email: [email protected] 1 Division of Sleep Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts 02215, USA. 2 The Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging, University College London, Queen Square, London WC1N 3BG. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 23, No. 3–4, 2016, pp. 245–54 246 J.A. HOBSON & K.J. FRISTON points — and then substantiate these points with more detailed argu- ments. -

An Affective Computational Model for Machine Consciousness

An affective computational model for machine consciousness Rohitash Chandra Artificial Intelligence and Cybernetics Research Group, Software Foundation, Nausori, Fiji Abstract In the past, several models of consciousness have become popular and have led to the development of models for machine con- sciousness with varying degrees of success and challenges for simulation and implementations. Moreover, affective computing attributes that involve emotions, behavior and personality have not been the focus of models of consciousness as they lacked moti- vation for deployment in software applications and robots. The affective attributes are important factors for the future of machine consciousness with the rise of technologies that can assist humans. Personality and affection hence can give an additional flavor for the computational model of consciousness in humanoid robotics. Recent advances in areas of machine learning with a focus on deep learning can further help in developing aspects of machine consciousness in areas that can better replicate human sensory per- ceptions such as speech recognition and vision. With such advancements, one encounters further challenges in developing models that can synchronize different aspects of affective computing. In this paper, we review some existing models of consciousnesses and present an affective computational model that would enable the human touch and feel for robotic systems. Keywords: Machine consciousness, cognitive systems, affective computing, consciousness, machine learning 1. Introduction that is not merely for survival. They feature social attributes such as empathy which is similar to humans [12, 13]. High The definition of consciousness has been a major challenge level of curiosity and creativity are major attributes of con- for simulating or modelling human consciousness [1,2]. -

A Traditional Scientific Perspective on the Integrated Information Theory Of

entropy Article A Traditional Scientific Perspective on the Integrated Information Theory of Consciousness Jon Mallatt The University of Washington WWAMI Medical Education Program at The University of Idaho, Moscow, ID 83844, USA; [email protected] Abstract: This paper assesses two different theories for explaining consciousness, a phenomenon that is widely considered amenable to scientific investigation despite its puzzling subjective aspects. I focus on Integrated Information Theory (IIT), which says that consciousness is integrated information (as φMax) and says even simple systems with interacting parts possess some consciousness. First, I evaluate IIT on its own merits. Second, I compare it to a more traditionally derived theory called Neurobiological Naturalism (NN), which says consciousness is an evolved, emergent feature of complex brains. Comparing these theories is informative because it reveals strengths and weaknesses of each, thereby suggesting better ways to study consciousness in the future. IIT’s strengths are the reasonable axioms at its core; its strong logic and mathematical formalism; its creative “experience- first” approach to studying consciousness; the way it avoids the mind-body (“hard”) problem; its consistency with evolutionary theory; and its many scientifically testable predictions. The potential weakness of IIT is that it contains stretches of logic-based reasoning that were not checked against hard evidence when the theory was being constructed, whereas scientific arguments require such supporting evidence to keep the reasoning on course. This is less of a concern for the other theory, NN, because it incorporated evidence much earlier in its construction process. NN is a less mature theory than IIT, less formalized and quantitative, and less well tested. -

Illusionism As the Obvious Default Theory of Consciousness

Daniel C. Dennett Illusionism as the Obvious Default Theory of Consciousness Abstract: Using a parallel with stage magic, it is argued that far from being seen as an extreme alternative, illusionism as articulated by Frankish should be considered the front runner, a conservative theory to be developed in detail, and abandoned only if it demonstrably fails to account for phenomena, not prematurely dismissed as ‘counter- intuitive’. We should explore the mundane possibilities thoroughly before investing in any magical hypotheses. Keith Frankish’s superb survey of the varieties of illusionism pro- vokes in me some reflections on what philosophy can offer to (cog- nitive) science, and why it so often manages instead to ensnarl itself in an internecine battle over details in ill-motivated ‘theories’ that, even Copyright (c) Imprint Academic 2016 if true, would be trivial and provide no substantial enlightenment on any topic, and no help at all to the baffled scientist. No wonder so For personal use only -- not for reproduction many scientists blithely ignore the philosophers’ tussles — while marching overconfidently into one abyss or another. The key for me lies in the everyday, non-philosophical meaning of the word illusionist. An illusionist is an expert in sleight-of-hand and the other devious methods of stage magic. We philosophical illusion- ists are also illusionists in the everyday sense — or should be. That is, our burden is to figure out and explain how the ‘magic’ is done. As Frankish says: Illusionism replaces the hard problem with the illusion problem — the problem of explaining how the illusion of phenomenality arises and Correspondence: Daniel C. -

How the Light Gets out by Michael Graziano 3500

Philosophy Science Psychology Health Society Technology Culture About Video Most popular Our writers How the light gets out by Michael Graziano 3500 Read later or Kindle Instapaper Kindle Illustration by Michael Marsicano Consciousness is the ‘hard problem’, the one that confounds science and philosophy. Has a new theory cracked it? Scientific talks can get a little dry, so I try to mix it up. I take out my giant hairy orangutan puppet, do some ventriloquism and quickly become entangled in an argument. I’ll be explaining my theory about how the brain — a biological machine — generates consciousness. Kevin, the orangutan, starts heckling me. ‘Yeah, well, I don’t have a brain. But I’m still conscious. What does that do to your theory?’ Kevin is the perfect introduction. Intellectually, nobody is fooled: we all know that there’s nothing inside. But everyone in the audience experiences an illusion of sentience emanating from his hairy head. The effect is automatic: being social animals, we project awareness onto the puppet. Indeed, part of the fun of ventriloquism is experiencing the illusion while knowing, on an intellectual level, that it isn’t real. Many thinkers have approached consciousness from a first-person vantage point, the kind of philosophical perspective according to which other people’s minds seem essentially unknowable. And yet, as Kevin shows, we spend a lot of mental energy attributing consciousness to other things. We can’t help it, and the fact that we can't help it ought to tell us something about what consciousness is and what it might be used for. -

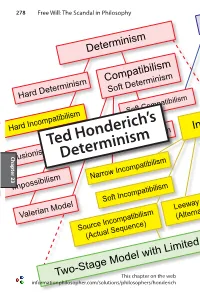

Ted Honderich's Determinism

278 Free Will: The Scandal in Philosophy Determinism Indeterminism Hard Determinism Compatibilism Libertarianism Soft Determinism Hard Incompatibilism Soft Compatibilism Event-Causal Agent-Causal Chapter 23 Chapter Ted Honderich’s Illusionism DeterminismSemicompatibilism Incompatibilism SFA Non-Causal Impossibilism Narrow Incompatibilism Broad Incompatibilism Soft Causality Valerian Model Soft Incompatibilism Modest Libertarianism Soft Libertarianism Source Incompatibilism Leeway Incompatibilism Cogito Daring Soft Libertarianism (Actual Sequence) (Alternative Sequences) informationphilosopher.com/solutions/philosophers/honderichTwo-Stage Model with Limited Determinism and Limited Indeterminism This chapter on the web Ted Honderich 279 Indeterminism Ted Honderich’s Determinism DeterminismLibertarianism Ted Honderich is the principal spokesman for strict physical causality and “hard determinism.” Agent-Causal He has written more widely (with excursions into quantum Compatibilism mechanics,Event-Causal neuroscience, and consciousness), more deeply, and Soft Determinism certainly more extensively than most of his colleagues on the Hard Determinism problem of free will. Unlike most of his determinist colleagues specializingNon-Causal in free will, Honderich has notSFA succumbed to the easy path of Soft Compatibilism compatibilism by simply declaring that the free will we have (and should want, says Daniel Dennett) is completely consistent Hard Incompatibilism Incompatibilismwith determinism, namely a HumeanSoft “voluntarism” Causality or “freedom