1 Realism V Equilibrism About Philosophy* Daniel Stoljar, ANU 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Just Deserts: the Dark Side of Moral Responsibility

(Un)just Deserts: The Dark Side of Moral Responsibility Gregg D. Caruso Corning Community College, SUNY What would be the consequence of embracing skepticism about free will and/or desert-based moral responsibility? What if we came to disbelieve in moral responsibility? What would this mean for our interpersonal re- lationships, society, morality, meaning, and the law? What would it do to our standing as human beings? Would it cause nihilism and despair as some maintain? Or perhaps increase anti-social behavior as some re- cent studies have suggested (Vohs and Schooler 2008; Baumeister, Masi- campo, and DeWall 2009)? Or would it rather have a humanizing effect on our practices and policies, freeing us from the negative effects of what Bruce Waller calls the “moral responsibility system” (2014, p. 4)? These questions are of profound pragmatic importance and should be of interest independent of the metaphysical debate over free will. As public procla- mations of skepticism continue to rise, and as the mass media continues to run headlines announcing free will and moral responsibility are illusions,1 we need to ask what effects this will have on the general public and what the responsibility is of professionals. In recent years a small industry has actually grown up around pre- cisely these questions. In the skeptical community, for example, a num- ber of different positions have been developed and advanced—including Saul Smilansky’s illusionism (2000), Thomas Nadelhoffer’s disillusionism (2011), Shaun Nichols’ anti-revolution (2007), and the optimistic skepti- cism of Derk Pereboom (2001, 2013a, 2013b), Bruce Waller (2011), Tam- ler Sommers (2005, 2007), and others. -

New Legal Realism at Ten Years and Beyond Bryant Garth

UC Irvine Law Review Volume 6 Article 3 Issue 2 The New Legal Realism at Ten Years 6-2016 Introduction: New Legal Realism at Ten Years and Beyond Bryant Garth Elizabeth Mertz Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.uci.edu/ucilr Part of the Law and Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Bryant Garth & Elizabeth Mertz, Introduction: New Legal Realism at Ten Years and Beyond, 6 U.C. Irvine L. Rev. 121 (2016). Available at: https://scholarship.law.uci.edu/ucilr/vol6/iss2/3 This Foreword is brought to you for free and open access by UCI Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in UC Irvine Law Review by an authorized editor of UCI Law Scholarly Commons. Garth & Mertz UPDATED 4.14.17 (Do Not Delete) 4/19/2017 9:40 AM Introduction: New Legal Realism at Ten Years and Beyond Bryant Garth* and Elizabeth Mertz** I. Celebrating Ten Years of New Legal Realism ........................................................ 121 II. A Developing Tradition ............................................................................................ 124 III. Current Realist Directions: The Symposium Articles ....................................... 131 Conclusion: Moving Forward ....................................................................................... 134 I. CELEBRATING TEN YEARS OF NEW LEGAL REALISM This symposium commemorates the tenth year that a body of research has formally flown under the banner of New Legal Realism (NLR).1 We are very pleased * Chancellor’s Professor of Law, University of California, Irvine School of Law; American Bar Foundation, Director Emeritus. ** Research Faculty, American Bar Foundation; John and Rylla Bosshard Professor, University of Wisconsin Law School. Many thanks are owed to Frances Tung for her help in overseeing part of the original Tenth Anniversary NLR conference, as well as in putting together some aspects of this Symposium. -

Distinguishing Science from Philosophy: a Critical Assessment of Thomas Nagel's Recommendation for Public Education Melissa Lammey

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 Distinguishing Science from Philosophy: A Critical Assessment of Thomas Nagel's Recommendation for Public Education Melissa Lammey Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS & SCIENCES DISTINGUISHING SCIENCE FROM PHILOSOPHY: A CRITICAL ASSESSMENT OF THOMAS NAGEL’S RECOMMENDATION FOR PUBLIC EDUCATION By MELISSA LAMMEY A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Philosophy in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2012 Melissa Lammey defended this dissertation on February 10, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Michael Ruse Professor Directing Dissertation Sherry Southerland University Representative Justin Leiber Committee Member Piers Rawling Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For Warren & Irene Wilson iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is my pleasure to acknowledge the contributions of Michael Ruse to my academic development. Without his direction, this dissertation would not have been possible and I am indebted to him for his patience, persistence, and guidance. I would also like to acknowledge the efforts of Sherry Southerland in helping me to learn more about science and science education and for her guidance throughout this project. In addition, I am grateful to Piers Rawling and Justin Leiber for their service on my committee. I would like to thank Stephen Konscol for his vital and continuing support. -

Contributors' Notes

Contributors' Notes Frances E. Dolan is Assistant Professor of English at Miami Univer- sity, Ohio. Her essays have appeared or are forthcoming in Medieval and Renaissance Drama, PMLA, and SEL. She is currently completing a book, DangerousFamiliars: PopularAccounts of Domestic Crime in Eng- land, 1550-1700, of which the present essay is a part. Barbara Taback Schneider is a 1990 graduate of Harvard Law School. She is currently an attorney in Portland, Maine, with the firm of Murray, Plumb & Murray. The paper on which her article was based received the Irving Oberman Memorial Award from the Law School for the best es- say by a graduating law student on a current legal topic. In 1990 that topic was legal history. Brian Leiter is a graduate student in philosophy at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, where he is writing a dissertation on Nietzche's critique of morality. A graduate of Princeton, he also holds a law degree from the University of Michigan and is a member of the New York Bar. John Martin Fischer received his Ph.D. in philosophy from Cornell University in 1982. He taught for seven years in the philosophy depart- ment at Yale University as an assistant and associate professor. He is currently Professor of Philosophy at the University of California, River- side. He has written on various topics in moral philosophy and meta- physics, especially free will and moral responsibility. Recently, he has published a book jointly edited with Mark Ravizza entitled Ethics: Problems and Principles (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1991). Mark Tushnet, Professor of Law, Georgetown University Law Center, has written on constitutional law and legal history. -

Book Reviews Did Formalism Never Exist?

BROPHY.FINAL.OC (DO NOT DELETE) 12/18/2013 9:48 AM Book Reviews Did Formalism Never Exist? BEYOND THE FORMALIST-REALIST DIVIDE: THE ROLE OF POLITICS IN JUDGING. By Brian Z. Tamanaha. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2010. 252 pages. $24.95. Reviewed by Alfred L. Brophy* In Beyond the Formalist-Realist Divide, Brian Tamanaha seeks to rewrite the story of the differences between the age of formalism and the age of legal realism. In essence, Tamanaha thinks there never was an age of formalism. For he sees legal thought even in the Gilded Age of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries—what is commonly known as the age of formalism1—as embracing what he terms “balanced realism.”2 Legal history3 and jurisprudence4 both make important use of that divide, or, to use somewhat less dramatic language, the shift from formalism (known often as classical legal thought) to realism. Moreover, as Tamanaha describes it, recent studies of judicial behavior that model the extent to which judges are formalist—that is, the extent to which they apply the law in some neutral fashion or, conversely, recognize the centrality of politics to * Judge John J. Parker Distinguished Professor of Law, University of North Carolina. I would like to thank Michael Deane, Arthur G. LeFrancois, Brian Leiter, David Rabban, Dana Remus, Stephen Siegel, and William Wiecek for help with this. 1. See, e.g., MORTON J. HORWITZ, THE TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICAN LAW 1870–1960, at 16–18 (1992) [hereinafter HORWITZ, TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICAN LAW 1870–1960] (discussing formalism, generally); MORTON J. -

How False Assumptions Still Haunt Theories of Consciousness

The Myth of When and Where: How False Assumptions Still Haunt Theories of Consciousness Sepehrdad Rahimian1 1 Department of Psychology, National Research University Higher School of Economics, Moscow, Russia * Correspondence: Sepehrdad Rahimian [email protected] Abstract Recent advances in Neural sciences have uncovered countless new facts about the brain. Although there is a plethora of theories of consciousness, it seems to some philosophers that there is still an explanatory gap when it comes to a scientific account of subjective experience. In what follows, I will argue why some of our more commonly acknowledged theories do not at all provide us with an account of subjective experience as they are built on false assumptions. These assumptions have led us into a state of cognitive dissonance between maintaining our standard scientific practices on one hand, and maintaining our folk notions on the other. I will then end by proposing Illusionism as the only option for a scientific investigation of consciousness and that even if ideas like panpsychism turn out to be holding the seemingly missing piece of the puzzle, the path to them must go through Illusionism. Keywords: Illusionism, Phenomenal consciousness, Predictive Processing, Consciousness, Cartesian Materialism, Unfolding argument 1. Introduction He once greeted me with the question: “Why do people say that it was natural to think that the sun went round the earth rather than that the earth turned on its axis?” I replied: “I suppose, because it looked as if the sun went round the earth.” “Well,” he asked, “what would it have looked like if it had looked as if the earth turned on its axis?” -Anscombe, G.E.M (1963), An introduction to Wittgenstein’s Tractatus In a 2011 paper, Anderson (2011) argued that different theories of attention suffer from somewhat arbitrary and often contradictory criteria for defining the term, rendering it more likely that we should be excluding the term “attention” from our scientific theories of the brain (Anderson, 2011). -

Illusionism As the Obvious Default Theory of Consciousness

Daniel C. Dennett Illusionism as the Obvious Default Theory of Consciousness Abstract: Using a parallel with stage magic, it is argued that far from being seen as an extreme alternative, illusionism as articulated by Frankish should be considered the front runner, a conservative theory to be developed in detail, and abandoned only if it demonstrably fails to account for phenomena, not prematurely dismissed as ‘counter- intuitive’. We should explore the mundane possibilities thoroughly before investing in any magical hypotheses. Keith Frankish’s superb survey of the varieties of illusionism pro- vokes in me some reflections on what philosophy can offer to (cog- nitive) science, and why it so often manages instead to ensnarl itself in an internecine battle over details in ill-motivated ‘theories’ that, even Copyright (c) Imprint Academic 2016 if true, would be trivial and provide no substantial enlightenment on any topic, and no help at all to the baffled scientist. No wonder so For personal use only -- not for reproduction many scientists blithely ignore the philosophers’ tussles — while marching overconfidently into one abyss or another. The key for me lies in the everyday, non-philosophical meaning of the word illusionist. An illusionist is an expert in sleight-of-hand and the other devious methods of stage magic. We philosophical illusion- ists are also illusionists in the everyday sense — or should be. That is, our burden is to figure out and explain how the ‘magic’ is done. As Frankish says: Illusionism replaces the hard problem with the illusion problem — the problem of explaining how the illusion of phenomenality arises and Correspondence: Daniel C. -

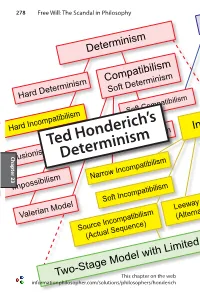

Ted Honderich's Determinism

278 Free Will: The Scandal in Philosophy Determinism Indeterminism Hard Determinism Compatibilism Libertarianism Soft Determinism Hard Incompatibilism Soft Compatibilism Event-Causal Agent-Causal Chapter 23 Chapter Ted Honderich’s Illusionism DeterminismSemicompatibilism Incompatibilism SFA Non-Causal Impossibilism Narrow Incompatibilism Broad Incompatibilism Soft Causality Valerian Model Soft Incompatibilism Modest Libertarianism Soft Libertarianism Source Incompatibilism Leeway Incompatibilism Cogito Daring Soft Libertarianism (Actual Sequence) (Alternative Sequences) informationphilosopher.com/solutions/philosophers/honderichTwo-Stage Model with Limited Determinism and Limited Indeterminism This chapter on the web Ted Honderich 279 Indeterminism Ted Honderich’s Determinism DeterminismLibertarianism Ted Honderich is the principal spokesman for strict physical causality and “hard determinism.” Agent-Causal He has written more widely (with excursions into quantum Compatibilism mechanics,Event-Causal neuroscience, and consciousness), more deeply, and Soft Determinism certainly more extensively than most of his colleagues on the Hard Determinism problem of free will. Unlike most of his determinist colleagues specializingNon-Causal in free will, Honderich has notSFA succumbed to the easy path of Soft Compatibilism compatibilism by simply declaring that the free will we have (and should want, says Daniel Dennett) is completely consistent Hard Incompatibilism Incompatibilismwith determinism, namely a HumeanSoft “voluntarism” Causality or “freedom -

Smilansky-Free-Will-Illusion.Pdf

IV*—FREE WILL: FROM NATURE TO ILLUSION by Saul Smilansky ABSTRACT Sir Peter Strawson’s ‘Freedom and Resentment’ was a landmark in the philosophical understanding of the free will problem. Building upon it, I attempt to defend a novel position, which purports to provide, in outline, the next step forward. The position presented is based on the descriptively central and normatively crucial role of illusion in the issue of free will. Illusion, I claim, is the vital but neglected key to the free will problem. The proposed position, which may be called ‘Illusionism’, is shown to follow both from the strengths and from the weaknesses of Strawson’s position. We have to believe in free will to get along. C.P. Snow ir Peter Strawson’s ‘Freedom and Resentment’ (1982, first Spublished in 1962) was a landmark in the philosophical understanding of the free will problem. It has been widely influ- ential and subjected to penetrating criticism (e.g. Galen Strawson 1986 Ch.5, Watson 1987, Klein 1990 Ch.6, Russell 1995 Ch.5). Most commentators have seen it as a large step forward over previous positions, but as ultimately unsuccessful. This is where the discussion within this philosophical direction has apparently stopped, which is obviously unsatisfactory. I shall attempt to defend a novel position, which purports to provide, in outline, the next step forward. The position presented is based on the descriptively central and normatively crucial role of illusion in the issue of free will. Illusion, I claim, is the vital but neglected key to the free will problem. -

Marxism and the Continuing Irrelevance of Normative Theory (Reviewing G

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 2002 Marxism and the Continuing Irrelevance of Normative Theory (reviewing G. A. Cohen, If You're an Egalitarian, How Come You're So Rich? (2000)) Brian Leiter Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Brian Leiter, "Marxism and the Continuing Irrelevance of Normative Theory (reviewing G. A. Cohen, If You're an Egalitarian, How Come You're So Rich? (2000))," 54 Stanford Law Review 1129 (2002). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOOK REVIEW Marxism and the Continuing Irrelevance of Normative Theory Brian Leiter* IF YOU'RE AN EGALITARIAN, How COME YOU'RE SO RICH? By G. A. Cohen. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000. 237 pp. $18.00. I. INTRODUCTION G. A. Cohen, the Chichele Professor of Social and Political Theory at Oxford, first came to international prominence with his impressive 1978 book on Marx's historical materialism,1 a volume which gave birth to "analytical Marxism."'2 Analytical Marxists reformulated, criticized, and tried to salvage central features of Marx's theories of history, ideology, politics, and economics. They did so not only by bringing a welcome argumentative rigor and clarity to the exposition of Marx's ideas, but also by purging Marxist thinking of what we may call its "Hegelian hangover," that is, its (sometimes tacit) commitment to Hegelian assumptions about matters of both philosophical substance and method. -

Law School News

LAW SCHOOL NEWS Volume 12, No. 25 November 6, 2002 View Past Issues FACULTY WRITINGS Kimberlee Kovach, Ethics for Whom? The Recognition of Diversity in Lawyering: Calls for Plurality in Ethical Considerations and Rules of Representational Work, IN DISPUTE RESOLUTION ETHICS: A COMPREHENSIVE GUIDE 57 (Phyllis Bernard & Bryant Garth eds.; Washington, D.C.: American Bar Association, Section of Dispute Resolution, 2002) Kimberlee Kovach, Enforcement of Ethics in Mediation, IN DISPUTE RESOLUTION ETHICS: A COMPREHENSIVE GUIDE 111 (Phyllis Bernard & Bryant Garth eds.; Washington, D.C.: American Bar Association, Section of Dispute Resolution, 2002) Douglas Laycock, Debate 2: Should the Government Provide Financial Support for Religious Institutions That Offer Faith-Based Social Services?, 3 RUTGERS JOURNAL OF LAW & RELIGION No. 5 (2001-2002) (with Louis H. Pollack, Glen A. Tobias, Erwin Chemerinsky, Barry W. Lynn, & Nathan J. Diament). Douglas Laycock, Injudicious: Liberals Should Get Tough on Bush's Conservative Judicial Nominees - And Stop Opposing Michael McConnell, THE AMERICAN PROSPECT ONLINE, Oct. 30, 2002, http://www.prospect.org/webfeatures/2002/10/laycock-d-10-30.html. Brian Leiter, The Fate of Genius, TIMES LITERARY SUPPLEMENT, Oct. 18, 2002, at 12 (reviewing Zarathustra's Secret: The Interior Life of Friedrich Nietzsche, by Joachim Köhler; Nietzsche: A Philosophical Biography, by Rüdiger Safranski; and The Legend of Nietzsche's Syphilis, by Richard Schain). Ronald Mann, Credit Cards and Debit Cards in the United States and Japan, 55 VANDERBILT LAW REVIEW 1055 (2002). Jane Stapleton, Lords a'Leaping Evidentiary Gaps, 10 TORTS LAW JOURNAL 276 (2002). FACULTY ACTIVITIES Lynn Baker spoke on "Professional Responsibility: Critical Mass Tort Settlement Considerations" at the Third Annual Class Action/Mass Tort Symposium held by the Louisiana State Bar Association in New Orleans, Oct. -

The Illusion of Realism in Film

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity Philosophy Faculty Research Philosophy Department 7-2002 The Illusion of Realism in Film Andrew Kania Trinity University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/phil_faculty Part of the Philosophy Commons Repository Citation Kania, A. (2002). The illusion of realism in film. British Journal of Aesthetics, 42(3), 243-258. doi:10.1093/ bjaesthetics/42.3.243 This Post-Print is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy Department at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Illusion of Realism in Film Andrew Kania [This is a pre-copyedited, author-produced PDF of an article accepted for publication in The British Journal of Aesthetics following peer review. The version of record (Andrew Kania, “The Illusion of Realism in Film” British Journal of Aesthetics 42 (2002): 243-58) is available online at: http://bjaesthetics.oxfordjournals.org/content/42/3/243.abstract?sid=31bb4bc4-514f- 46ef-9efc-c7b4544506d4. Please cite only the published version.] The moviegoer’s brain, hoodwinked by this succession of still lives, obligingly infers motion. − Nicholson Baker, “The Projector”1 In “Film, Reality, and Illusion,”2 one of his many concentrated yet lucid writings on film, Gregory Currie argues, among other things, that when we watch a film we have the impression that we are seeing a ‘moving picture’ not because of an illusion perpetrated against our visual faculty, but because the images that we see up on the screen really are moving.