Illusionism As a Theory of Consciousness*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dennett's Dual-Process Theory of Reasoning ∗

∗∗∗ Dennett’s dual-process theory of reasoning Keith Frankish 1. Introduction Content and Consciousness (hereafter, C&C) 1 outlined an elegant and powerful framework for thinking about the relation between mind and brain and about how science can inform our understanding of the mind. By locating everyday mentalistic explanations at the personal level of whole, environmentally embedded organisms, and related scientific explanations at the subpersonal level of internal informational states and processes, and by judicious reflections on the relations between these levels, Dennett showed how we can avoid the complementary errors of treating mental states as independent of the brain and of projecting mentalistic categories onto the brain. In this way, combining cognitivism with insights from logical behaviourism, we can halt the swinging of the philosophical pendulum between the “ontic bulge” of dualism (C&C, p.5) and the confused or implausible identities posited by some brands of materialism, thereby freeing ourselves to focus on the truly fruitful question of how the brain can perform feats that warrant the ascription of thoughts and experiences to the organism that possesses it. The main themes of the book are, of course, intentionality and experience – content and consciousness. Dennett has substantially expanded and revised his views on these topics over the years, though without abandoning the foundations laid down in C&C, and his views have been voluminously discussed in the associated literature. In the field of intentionality, the major lessons of C&C have been widely accepted – and there can be no higher praise than to say that claims that seemed radical forty-odd years ago now seem obvious. -

Poetry and the Multiple Drafts Model: the Functional Similarity of Cole Swensen's Verse and Human Consciousness

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 6-1-2011 Poetry and the Multiple Drafts Model: The Functional Similarity of Cole Swensen's Verse and Human Consciousness Connor Ryan Kreimeyer Fisher University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons, and the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Fisher, Connor Ryan Kreimeyer, "Poetry and the Multiple Drafts Model: The Functional Similarity of Cole Swensen's Verse and Human Consciousness" (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 202. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/202 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. POETRY AND THE MULTIPLE DRAFTS MODEL: THE FUNCTIONAL SIMILARITY OF COLE SWENSEN’S VERSE AND HUMAN CONSCIOUSNESS __________ A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Arts and Humanities University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts __________ by Connor Ryan Kreimeyer Fisher June 2011 Advisor: W. Scott Howard Author: Connor Ryan Kreimeyer Fisher Title: POETRY AND THE MULTIPLE DRAFTS MODEL: THE FUNCTIONAL SIMILARITY OF COLE SWENSEN’S VERSE AND HUMAN CONSCIOUSNESS Advisor: W. Scott Howard Degree Date: June 2011 Abstract This project compares the operational methods of three of Cole Swensen’s books of poetry (Such Rich Hour , Try , and Goest ) with ways in which the human mind and consciousness function. -

Just Deserts: the Dark Side of Moral Responsibility

(Un)just Deserts: The Dark Side of Moral Responsibility Gregg D. Caruso Corning Community College, SUNY What would be the consequence of embracing skepticism about free will and/or desert-based moral responsibility? What if we came to disbelieve in moral responsibility? What would this mean for our interpersonal re- lationships, society, morality, meaning, and the law? What would it do to our standing as human beings? Would it cause nihilism and despair as some maintain? Or perhaps increase anti-social behavior as some re- cent studies have suggested (Vohs and Schooler 2008; Baumeister, Masi- campo, and DeWall 2009)? Or would it rather have a humanizing effect on our practices and policies, freeing us from the negative effects of what Bruce Waller calls the “moral responsibility system” (2014, p. 4)? These questions are of profound pragmatic importance and should be of interest independent of the metaphysical debate over free will. As public procla- mations of skepticism continue to rise, and as the mass media continues to run headlines announcing free will and moral responsibility are illusions,1 we need to ask what effects this will have on the general public and what the responsibility is of professionals. In recent years a small industry has actually grown up around pre- cisely these questions. In the skeptical community, for example, a num- ber of different positions have been developed and advanced—including Saul Smilansky’s illusionism (2000), Thomas Nadelhoffer’s disillusionism (2011), Shaun Nichols’ anti-revolution (2007), and the optimistic skepti- cism of Derk Pereboom (2001, 2013a, 2013b), Bruce Waller (2011), Tam- ler Sommers (2005, 2007), and others. -

Searle's Critique of the Multiple Drafts Model of Consciousness 1

FACTA UNIVERSITATIS Series: Linguistics and Literature Vol. 7, No 2, 2009, pp. 173 - 182 SEARLE'S CRITIQUE OF THE MULTIPLE DRAFTS MODEL OF CONSCIOUSNESS 1 UDC 81'23(049.32) Đorđe Vidanović Faculty of Philosophy, University of Niš, Serbia E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. In this paper I try to show the limitations of John Searle's critique of Daniel Dennett's conception of consciousness based on the idea that the computational architecture of consciousness is patterned on the simple replicating units of information called memes. Searle claims that memes cannot substitute virtual genes as expounded by Dennett, saying that the spread of ideas and information is not driven by "blind forces" but has to be intentional. In this paper I try to refute his argumentation by a detailed account that tries to prove that intentionality need not be invoked in accounts of memes (and consciousness). Key words: Searle, Dennett, Multiple Drafts Model, consciousness,memes, genes, intentionality "No activity of mind is ever conscious" 2 (Karl Lashley, 1956) 1. INTRODUCTION In his collection of the New York Times book reviews, The Mystery of Conscious- ness (1997), John Searle criticizes Daniel Dennett's explanation of consciousness, stating that Dennett actually renounces it and proposes a version of strong AI instead, without ever accounting for it. Received June 27, 2009 1 A version of this paper was submitted to the Department of Philosophy of the University of Maribor, Slovenia, as part of the Festschrift for Dunja Jutronic in 2008, see http://oddelki.ff.uni-mb.si/filozofija/files/Festschrift/Dunjas_festschrift/vidanovic.pdf 2 Lashley, K. -

Rmeyersdissertation2002.Pdf (1.831Mb)

A HEURISTIC FOR ENVIRONMENTAL VALUES AND ETHICS, AND A PSYCHOMETRIC INSTRUMENT TO MEASURE ADULT ENVIRONMENTAL ETHICS AND WILLINGNESS TO PROTECT THE ENVIRONMENT DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Ronald B. Meyers, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2002 Dissertation Committee: Joe E. Heimlich, Adviser Approved by Herbert Asher Donald C. Hubin __________________________ Tomas Koontz Adviser Graduate Program in Natural Resource Copyright by Ronald Bennett Meyers 2002 ABSTRACT The need for instruments to objectively and deeply measure public beliefs concerning environmental values and ethics, and relationship to environmental protection led to a project to integrate analytical techniques from ethics and educational psychology to identify beliefs in theories of value and obligation (direct and indirect), develop a 12- category system of environmental ethics, and a psychometric instrument with 5 scales and 7 subscales, including a self-assessment instrument for environmental ethics. The ethics were tested for ability to distinguish between beliefs in need to protect environment for human interests versus the interests or rights of animals and the environment. A heuristic for educators was developed for considering 9 dimensions of environmental and the ethics, and tested favorably. An exploratory survey (N = 74, 2001) of adult moral beliefs used 16 open-ended questions for moral considerability of, rights, treatment, and direct and indirect moral obligations to the environment. A 465 - item question bank was developed and administered (N = 191, 2002) to Ohio adults, and reduced to 73 items in 12 Likert-type scales (1-7, 1 strongly disagree) by analyzing internal consistency, response variability, interscale correlations, factorial, and ANOVA. -

Dual-System Theories and the Personal– Subpersonal Distinction ∗ Keith Frankish

Systems and levels: Dual-system theories and the personal– subpersonal distinction ∗ Keith Frankish 1. Introduction There is now abundant evidence for the existence of two types of processing in human reasoning, decision making, and social cognition — one type fast, automatic, effortless, and non-conscious, the other slow, controlled, effortful, and conscious — which may deliver different and sometimes conflicting results (for a review, see Evans 2008). More recently, some cognitive psychologists have proposed ambitious theories of cognitive architecture, according to which humans possess two distinct reasoning systems — two minds, in fact — now widely referred to as System 1 and System 2 (Evans 2003; Evans and Over 1996; Kahneman and Frederick 2002; Sloman 1996, 2002; Stanovich 1999, 2004, this volume). A composite characterization of the two systems runs as follows. System 1 is a collection of autonomous subsystems, many of which are old in evolutionary terms and whose operations are fast, automatic, effortless, non-conscious, parallel, shaped by biology and personal experience, and independent of working memory and general intelligence. System 2 is more recent, and its processes are slow, controlled, effortful, conscious, serial, shaped by culture and formal tuition, demanding of working memory, and related to general intelligence. In addition, it is often claimed that the two systems employ different procedures and serve different goals, with System 1 being highly contextualized, associative, heuristic, and directed to goals that serve the reproductive interests of our genes, and System 2 being decontextualized, rule-governed, analytic, and serving our goals as individuals. This is a very strong hypothesis, and theorists are already recognizing that it requires substantial qualification and complication (Evans 2006a, 2008, this volume; Stanovich this volume; Samuels, this volume). -

1 Realism V Equilibrism About Philosophy* Daniel Stoljar, ANU 1

Realism v Equilibrism about Philosophy* Daniel Stoljar, ANU Abstract: According to the realist about philosophy, the goal of philosophy is to come to know the truth about philosophical questions; according to what Helen Beebee calls equilibrism, by contrast, the goal is rather to place one’s commitments in a coherent system. In this paper, I present a critique of equilibrism in the form Beebee defends it, paying particular attention to her suggestion that various meta-philosophical remarks made by David Lewis may be recruited to defend equilibrism. At the end of the paper, I point out that a realist about philosophy may also be a pluralist about philosophical culture, thus undermining one main motivation for equilibrism. 1. Realism about Philosophy What is the goal of philosophy? According to the realist, the goal is to come to know the truth about philosophical questions. Do we have free will? Are morality and rationality objective? Is consciousness a fundamental feature of the world? From a realist point of view, there are truths that answer these questions, and what we are trying to do in philosophy is to come to know these truths. Of course, nobody thinks it’s easy, or at least nobody should. Looking over the history of philosophy, some people (I won’t mention any names) seem to succumb to a kind of triumphalism. Perhaps a bit of logic or physics or psychology, or perhaps just a bit of clear thinking, is all you need to solve once and for all the problems philosophers are interested in. Whether those who apparently hold such views really do is a difficult question. -

How False Assumptions Still Haunt Theories of Consciousness

The Myth of When and Where: How False Assumptions Still Haunt Theories of Consciousness Sepehrdad Rahimian1 1 Department of Psychology, National Research University Higher School of Economics, Moscow, Russia * Correspondence: Sepehrdad Rahimian [email protected] Abstract Recent advances in Neural sciences have uncovered countless new facts about the brain. Although there is a plethora of theories of consciousness, it seems to some philosophers that there is still an explanatory gap when it comes to a scientific account of subjective experience. In what follows, I will argue why some of our more commonly acknowledged theories do not at all provide us with an account of subjective experience as they are built on false assumptions. These assumptions have led us into a state of cognitive dissonance between maintaining our standard scientific practices on one hand, and maintaining our folk notions on the other. I will then end by proposing Illusionism as the only option for a scientific investigation of consciousness and that even if ideas like panpsychism turn out to be holding the seemingly missing piece of the puzzle, the path to them must go through Illusionism. Keywords: Illusionism, Phenomenal consciousness, Predictive Processing, Consciousness, Cartesian Materialism, Unfolding argument 1. Introduction He once greeted me with the question: “Why do people say that it was natural to think that the sun went round the earth rather than that the earth turned on its axis?” I replied: “I suppose, because it looked as if the sun went round the earth.” “Well,” he asked, “what would it have looked like if it had looked as if the earth turned on its axis?” -Anscombe, G.E.M (1963), An introduction to Wittgenstein’s Tractatus In a 2011 paper, Anderson (2011) argued that different theories of attention suffer from somewhat arbitrary and often contradictory criteria for defining the term, rendering it more likely that we should be excluding the term “attention” from our scientific theories of the brain (Anderson, 2011). -

Illusionism As the Obvious Default Theory of Consciousness

Daniel C. Dennett Illusionism as the Obvious Default Theory of Consciousness Abstract: Using a parallel with stage magic, it is argued that far from being seen as an extreme alternative, illusionism as articulated by Frankish should be considered the front runner, a conservative theory to be developed in detail, and abandoned only if it demonstrably fails to account for phenomena, not prematurely dismissed as ‘counter- intuitive’. We should explore the mundane possibilities thoroughly before investing in any magical hypotheses. Keith Frankish’s superb survey of the varieties of illusionism pro- vokes in me some reflections on what philosophy can offer to (cog- nitive) science, and why it so often manages instead to ensnarl itself in an internecine battle over details in ill-motivated ‘theories’ that, even Copyright (c) Imprint Academic 2016 if true, would be trivial and provide no substantial enlightenment on any topic, and no help at all to the baffled scientist. No wonder so For personal use only -- not for reproduction many scientists blithely ignore the philosophers’ tussles — while marching overconfidently into one abyss or another. The key for me lies in the everyday, non-philosophical meaning of the word illusionist. An illusionist is an expert in sleight-of-hand and the other devious methods of stage magic. We philosophical illusion- ists are also illusionists in the everyday sense — or should be. That is, our burden is to figure out and explain how the ‘magic’ is done. As Frankish says: Illusionism replaces the hard problem with the illusion problem — the problem of explaining how the illusion of phenomenality arises and Correspondence: Daniel C. -

The Contemporary Relevance of Kant's Transcendental Psychology

The Contemporary Relevance of Kant’s Transcendental Psychology Deborah Maxwell Alamé-Jones BA (Hons) Supervisor: Dr David Morgans Submitted in partial fulfilment for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy UNIVERSITY OF WALES TRINITY SAINT DAVID 2018 DECLARATION SHEET This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed .......Deborah Alame-Jones........................................................... Date .............. 17th May 2018.......................................................... STATEMENT 1 This thesis is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated. Sources are acknowledged by giving explicit references in the body of the text. A bibliography is appended. Signed ........ Deborah Alame-Jones............................................................. Date .............. 17th May 2018.......................................................... STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed .......... Deborah Alame-Jones........................................................... Date .............. 17th May 2018.......................................................... STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for deposit in the University’s digital repository. Signed ........... Deborah Alame-Jones......................................................... -

A Defense of a Sentiocentric Approach to Environmental Ethics

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 8-2012 Minding Nature: A Defense of a Sentiocentric Approach to Environmental Ethics Joel P. MacClellan University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Ethics and Political Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation MacClellan, Joel P., "Minding Nature: A Defense of a Sentiocentric Approach to Environmental Ethics. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2012. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/1433 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Joel P. MacClellan entitled "Minding Nature: A Defense of a Sentiocentric Approach to Environmental Ethics." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Philosophy. John Nolt, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Jon Garthoff, David Reidy, Dan Simberloff Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) MINDING NATURE: A DEFENSE OF A SENTIOCENTRIC APPROACH TO ENVIRONMENTAL ETHICS A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Joel Patrick MacClellan August 2012 ii The sedge is wither’d from the lake, And no birds sing. -

Ted Honderich's Determinism

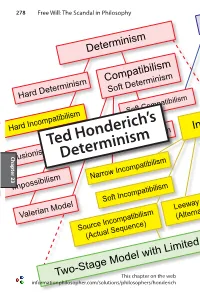

278 Free Will: The Scandal in Philosophy Determinism Indeterminism Hard Determinism Compatibilism Libertarianism Soft Determinism Hard Incompatibilism Soft Compatibilism Event-Causal Agent-Causal Chapter 23 Chapter Ted Honderich’s Illusionism DeterminismSemicompatibilism Incompatibilism SFA Non-Causal Impossibilism Narrow Incompatibilism Broad Incompatibilism Soft Causality Valerian Model Soft Incompatibilism Modest Libertarianism Soft Libertarianism Source Incompatibilism Leeway Incompatibilism Cogito Daring Soft Libertarianism (Actual Sequence) (Alternative Sequences) informationphilosopher.com/solutions/philosophers/honderichTwo-Stage Model with Limited Determinism and Limited Indeterminism This chapter on the web Ted Honderich 279 Indeterminism Ted Honderich’s Determinism DeterminismLibertarianism Ted Honderich is the principal spokesman for strict physical causality and “hard determinism.” Agent-Causal He has written more widely (with excursions into quantum Compatibilism mechanics,Event-Causal neuroscience, and consciousness), more deeply, and Soft Determinism certainly more extensively than most of his colleagues on the Hard Determinism problem of free will. Unlike most of his determinist colleagues specializingNon-Causal in free will, Honderich has notSFA succumbed to the easy path of Soft Compatibilism compatibilism by simply declaring that the free will we have (and should want, says Daniel Dennett) is completely consistent Hard Incompatibilism Incompatibilismwith determinism, namely a HumeanSoft “voluntarism” Causality or “freedom