Illusionism As the Obvious Default Theory of Consciousness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dennett's Dual-Process Theory of Reasoning ∗

∗∗∗ Dennett’s dual-process theory of reasoning Keith Frankish 1. Introduction Content and Consciousness (hereafter, C&C) 1 outlined an elegant and powerful framework for thinking about the relation between mind and brain and about how science can inform our understanding of the mind. By locating everyday mentalistic explanations at the personal level of whole, environmentally embedded organisms, and related scientific explanations at the subpersonal level of internal informational states and processes, and by judicious reflections on the relations between these levels, Dennett showed how we can avoid the complementary errors of treating mental states as independent of the brain and of projecting mentalistic categories onto the brain. In this way, combining cognitivism with insights from logical behaviourism, we can halt the swinging of the philosophical pendulum between the “ontic bulge” of dualism (C&C, p.5) and the confused or implausible identities posited by some brands of materialism, thereby freeing ourselves to focus on the truly fruitful question of how the brain can perform feats that warrant the ascription of thoughts and experiences to the organism that possesses it. The main themes of the book are, of course, intentionality and experience – content and consciousness. Dennett has substantially expanded and revised his views on these topics over the years, though without abandoning the foundations laid down in C&C, and his views have been voluminously discussed in the associated literature. In the field of intentionality, the major lessons of C&C have been widely accepted – and there can be no higher praise than to say that claims that seemed radical forty-odd years ago now seem obvious. -

Just Deserts: the Dark Side of Moral Responsibility

(Un)just Deserts: The Dark Side of Moral Responsibility Gregg D. Caruso Corning Community College, SUNY What would be the consequence of embracing skepticism about free will and/or desert-based moral responsibility? What if we came to disbelieve in moral responsibility? What would this mean for our interpersonal re- lationships, society, morality, meaning, and the law? What would it do to our standing as human beings? Would it cause nihilism and despair as some maintain? Or perhaps increase anti-social behavior as some re- cent studies have suggested (Vohs and Schooler 2008; Baumeister, Masi- campo, and DeWall 2009)? Or would it rather have a humanizing effect on our practices and policies, freeing us from the negative effects of what Bruce Waller calls the “moral responsibility system” (2014, p. 4)? These questions are of profound pragmatic importance and should be of interest independent of the metaphysical debate over free will. As public procla- mations of skepticism continue to rise, and as the mass media continues to run headlines announcing free will and moral responsibility are illusions,1 we need to ask what effects this will have on the general public and what the responsibility is of professionals. In recent years a small industry has actually grown up around pre- cisely these questions. In the skeptical community, for example, a num- ber of different positions have been developed and advanced—including Saul Smilansky’s illusionism (2000), Thomas Nadelhoffer’s disillusionism (2011), Shaun Nichols’ anti-revolution (2007), and the optimistic skepti- cism of Derk Pereboom (2001, 2013a, 2013b), Bruce Waller (2011), Tam- ler Sommers (2005, 2007), and others. -

Dual-System Theories and the Personal– Subpersonal Distinction ∗ Keith Frankish

Systems and levels: Dual-system theories and the personal– subpersonal distinction ∗ Keith Frankish 1. Introduction There is now abundant evidence for the existence of two types of processing in human reasoning, decision making, and social cognition — one type fast, automatic, effortless, and non-conscious, the other slow, controlled, effortful, and conscious — which may deliver different and sometimes conflicting results (for a review, see Evans 2008). More recently, some cognitive psychologists have proposed ambitious theories of cognitive architecture, according to which humans possess two distinct reasoning systems — two minds, in fact — now widely referred to as System 1 and System 2 (Evans 2003; Evans and Over 1996; Kahneman and Frederick 2002; Sloman 1996, 2002; Stanovich 1999, 2004, this volume). A composite characterization of the two systems runs as follows. System 1 is a collection of autonomous subsystems, many of which are old in evolutionary terms and whose operations are fast, automatic, effortless, non-conscious, parallel, shaped by biology and personal experience, and independent of working memory and general intelligence. System 2 is more recent, and its processes are slow, controlled, effortful, conscious, serial, shaped by culture and formal tuition, demanding of working memory, and related to general intelligence. In addition, it is often claimed that the two systems employ different procedures and serve different goals, with System 1 being highly contextualized, associative, heuristic, and directed to goals that serve the reproductive interests of our genes, and System 2 being decontextualized, rule-governed, analytic, and serving our goals as individuals. This is a very strong hypothesis, and theorists are already recognizing that it requires substantial qualification and complication (Evans 2006a, 2008, this volume; Stanovich this volume; Samuels, this volume). -

1 Realism V Equilibrism About Philosophy* Daniel Stoljar, ANU 1

Realism v Equilibrism about Philosophy* Daniel Stoljar, ANU Abstract: According to the realist about philosophy, the goal of philosophy is to come to know the truth about philosophical questions; according to what Helen Beebee calls equilibrism, by contrast, the goal is rather to place one’s commitments in a coherent system. In this paper, I present a critique of equilibrism in the form Beebee defends it, paying particular attention to her suggestion that various meta-philosophical remarks made by David Lewis may be recruited to defend equilibrism. At the end of the paper, I point out that a realist about philosophy may also be a pluralist about philosophical culture, thus undermining one main motivation for equilibrism. 1. Realism about Philosophy What is the goal of philosophy? According to the realist, the goal is to come to know the truth about philosophical questions. Do we have free will? Are morality and rationality objective? Is consciousness a fundamental feature of the world? From a realist point of view, there are truths that answer these questions, and what we are trying to do in philosophy is to come to know these truths. Of course, nobody thinks it’s easy, or at least nobody should. Looking over the history of philosophy, some people (I won’t mention any names) seem to succumb to a kind of triumphalism. Perhaps a bit of logic or physics or psychology, or perhaps just a bit of clear thinking, is all you need to solve once and for all the problems philosophers are interested in. Whether those who apparently hold such views really do is a difficult question. -

How False Assumptions Still Haunt Theories of Consciousness

The Myth of When and Where: How False Assumptions Still Haunt Theories of Consciousness Sepehrdad Rahimian1 1 Department of Psychology, National Research University Higher School of Economics, Moscow, Russia * Correspondence: Sepehrdad Rahimian [email protected] Abstract Recent advances in Neural sciences have uncovered countless new facts about the brain. Although there is a plethora of theories of consciousness, it seems to some philosophers that there is still an explanatory gap when it comes to a scientific account of subjective experience. In what follows, I will argue why some of our more commonly acknowledged theories do not at all provide us with an account of subjective experience as they are built on false assumptions. These assumptions have led us into a state of cognitive dissonance between maintaining our standard scientific practices on one hand, and maintaining our folk notions on the other. I will then end by proposing Illusionism as the only option for a scientific investigation of consciousness and that even if ideas like panpsychism turn out to be holding the seemingly missing piece of the puzzle, the path to them must go through Illusionism. Keywords: Illusionism, Phenomenal consciousness, Predictive Processing, Consciousness, Cartesian Materialism, Unfolding argument 1. Introduction He once greeted me with the question: “Why do people say that it was natural to think that the sun went round the earth rather than that the earth turned on its axis?” I replied: “I suppose, because it looked as if the sun went round the earth.” “Well,” he asked, “what would it have looked like if it had looked as if the earth turned on its axis?” -Anscombe, G.E.M (1963), An introduction to Wittgenstein’s Tractatus In a 2011 paper, Anderson (2011) argued that different theories of attention suffer from somewhat arbitrary and often contradictory criteria for defining the term, rendering it more likely that we should be excluding the term “attention” from our scientific theories of the brain (Anderson, 2011). -

The Contemporary Relevance of Kant's Transcendental Psychology

The Contemporary Relevance of Kant’s Transcendental Psychology Deborah Maxwell Alamé-Jones BA (Hons) Supervisor: Dr David Morgans Submitted in partial fulfilment for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy UNIVERSITY OF WALES TRINITY SAINT DAVID 2018 DECLARATION SHEET This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed .......Deborah Alame-Jones........................................................... Date .............. 17th May 2018.......................................................... STATEMENT 1 This thesis is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated. Sources are acknowledged by giving explicit references in the body of the text. A bibliography is appended. Signed ........ Deborah Alame-Jones............................................................. Date .............. 17th May 2018.......................................................... STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed .......... Deborah Alame-Jones........................................................... Date .............. 17th May 2018.......................................................... STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for deposit in the University’s digital repository. Signed ........... Deborah Alame-Jones......................................................... -

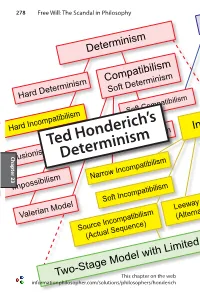

Ted Honderich's Determinism

278 Free Will: The Scandal in Philosophy Determinism Indeterminism Hard Determinism Compatibilism Libertarianism Soft Determinism Hard Incompatibilism Soft Compatibilism Event-Causal Agent-Causal Chapter 23 Chapter Ted Honderich’s Illusionism DeterminismSemicompatibilism Incompatibilism SFA Non-Causal Impossibilism Narrow Incompatibilism Broad Incompatibilism Soft Causality Valerian Model Soft Incompatibilism Modest Libertarianism Soft Libertarianism Source Incompatibilism Leeway Incompatibilism Cogito Daring Soft Libertarianism (Actual Sequence) (Alternative Sequences) informationphilosopher.com/solutions/philosophers/honderichTwo-Stage Model with Limited Determinism and Limited Indeterminism This chapter on the web Ted Honderich 279 Indeterminism Ted Honderich’s Determinism DeterminismLibertarianism Ted Honderich is the principal spokesman for strict physical causality and “hard determinism.” Agent-Causal He has written more widely (with excursions into quantum Compatibilism mechanics,Event-Causal neuroscience, and consciousness), more deeply, and Soft Determinism certainly more extensively than most of his colleagues on the Hard Determinism problem of free will. Unlike most of his determinist colleagues specializingNon-Causal in free will, Honderich has notSFA succumbed to the easy path of Soft Compatibilism compatibilism by simply declaring that the free will we have (and should want, says Daniel Dennett) is completely consistent Hard Incompatibilism Incompatibilismwith determinism, namely a HumeanSoft “voluntarism” Causality or “freedom -

Smilansky-Free-Will-Illusion.Pdf

IV*—FREE WILL: FROM NATURE TO ILLUSION by Saul Smilansky ABSTRACT Sir Peter Strawson’s ‘Freedom and Resentment’ was a landmark in the philosophical understanding of the free will problem. Building upon it, I attempt to defend a novel position, which purports to provide, in outline, the next step forward. The position presented is based on the descriptively central and normatively crucial role of illusion in the issue of free will. Illusion, I claim, is the vital but neglected key to the free will problem. The proposed position, which may be called ‘Illusionism’, is shown to follow both from the strengths and from the weaknesses of Strawson’s position. We have to believe in free will to get along. C.P. Snow ir Peter Strawson’s ‘Freedom and Resentment’ (1982, first Spublished in 1962) was a landmark in the philosophical understanding of the free will problem. It has been widely influ- ential and subjected to penetrating criticism (e.g. Galen Strawson 1986 Ch.5, Watson 1987, Klein 1990 Ch.6, Russell 1995 Ch.5). Most commentators have seen it as a large step forward over previous positions, but as ultimately unsuccessful. This is where the discussion within this philosophical direction has apparently stopped, which is obviously unsatisfactory. I shall attempt to defend a novel position, which purports to provide, in outline, the next step forward. The position presented is based on the descriptively central and normatively crucial role of illusion in the issue of free will. Illusion, I claim, is the vital but neglected key to the free will problem. -

The Illusion of Realism in Film

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity Philosophy Faculty Research Philosophy Department 7-2002 The Illusion of Realism in Film Andrew Kania Trinity University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/phil_faculty Part of the Philosophy Commons Repository Citation Kania, A. (2002). The illusion of realism in film. British Journal of Aesthetics, 42(3), 243-258. doi:10.1093/ bjaesthetics/42.3.243 This Post-Print is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy Department at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Illusion of Realism in Film Andrew Kania [This is a pre-copyedited, author-produced PDF of an article accepted for publication in The British Journal of Aesthetics following peer review. The version of record (Andrew Kania, “The Illusion of Realism in Film” British Journal of Aesthetics 42 (2002): 243-58) is available online at: http://bjaesthetics.oxfordjournals.org/content/42/3/243.abstract?sid=31bb4bc4-514f- 46ef-9efc-c7b4544506d4. Please cite only the published version.] The moviegoer’s brain, hoodwinked by this succession of still lives, obligingly infers motion. − Nicholson Baker, “The Projector”1 In “Film, Reality, and Illusion,”2 one of his many concentrated yet lucid writings on film, Gregory Currie argues, among other things, that when we watch a film we have the impression that we are seeing a ‘moving picture’ not because of an illusion perpetrated against our visual faculty, but because the images that we see up on the screen really are moving. -

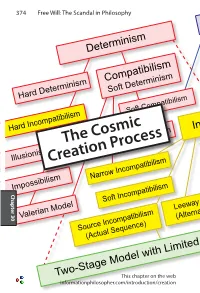

The Cosmic Creation Process 375 Indeterminism the Cosmic Creation Process Cosmic Creationlibertarianism Is Horrendously Wasteful

374 Free Will: The Scandal in Philosophy Determinism Indeterminism Hard Determinism Compatibilism Libertarianism Soft Determinism Hard Incompatibilism Soft Compatibilism Event-Causal Agent-Causal The Cosmic Illusionism Semicompatibilism Creation Process Incompatibilism SFA Non-Causal Impossibilism Chapter 30 Chapter Narrow Incompatibilism Broad Incompatibilism Soft Causality Valerian Model Soft Incompatibilism Modest Libertarianism Soft Libertarianism Source Incompatibilism Leeway Incompatibilism Cogito Daring Soft Libertarianism (Actual Sequence) (Alternative Sequences) Two-Stage Model with Limited Determinism and Limited Indeterminism informationphilosopher.com/introduction/creation This chapter on the web The Cosmic Creation Process 375 Indeterminism The Cosmic Creation Process Cosmic creationLibertarianism is horrendously wasteful. In the existential Determinism balance between the forces of destruction and the forces of con- struction, there is no contest. The dark side is overwhelming. By quantitative physical measures of matter andAgent-Causal energy content, there is far more chaos than cosmos in our universe. But it is the Compatibilism cosmos that we prize. As we sawEvent-Causal in the introduction, my philosophy focuses on the Soft Determinism qualitatively valuable information structures in the universe. The Hard Determinism destructive forces are entropic, they increase the entropyNon-Causal and dis- order. The constructive forces are anti-entropic. They increase the Soft Compatibilism order and information. SFA The fundamental question of information philosophy is there- Incompatibilismfore cosmological and ultimately metaphysical. Hard Incompatibilism What creates the information structuresSoft in theCausality universe? At the starting point, the archē (ἡ ἀρχή), the origin of the Semicompatibilism universe, all was light - pure radiation, at an extraordinarily high Broad Incompatibilismtemperature. As the universe expanded, theSoft temperature Libertarianism of the Illusionism radiation fell. -

Illusionism As a Theory of Consciousness*

Illusionism as a Theory of Consciousness Keith Frankish So, if he’s doing it by divine means, I can only tell him this: ‘Mr Geller, you’re doing it the hard way.’ (James Randi, 1997, p. 174) Theories of consciousness typically address the hard problem. They accept that phenomenal consciousness is real and aim to explain how it comes to exist. There is, however, another approach, which holds that phenomenal consciousness is an illusion and aims to explain why it seems to exist. We might call this eliminativism about phenomenal consciousness. The term is not ideal, however, suggesting as it does that belief in phenomenal consciousness is simply a theoretical error, that rejection of phenomenal realism is part of a wider rejection of folk psychology, and that there is no role at all for talk of phenomenal properties — claims that are not essential to the approach. Another label is ‘irrealism’, but that too has unwanted connotations; illusions themselves are real and may have considerable power. I propose ‘illusionism’ as a more accurate and inclusive name, and I shall refer to the problem of explaining why experiences seem to have phenomenal properties as the illusion problem .1 Although it has powerful defenders — pre-eminently Daniel Dennett — illusionism remains a minority position, and it is often dismissed out of hand as failing to ‘take consciousness seriously’ (Chalmers, 1996). The aim of this article is to present the case for illusionism. It will not propose a detailed illusionist theory, but will seek to persuade the reader that the illusionist research programme is worth pursuing and that illusionists do take consciousness seriously — in some ways, more seriously than realists do. -

Download Link

KEITH FRANKISH Curriculum vitae 18/10/18 www.keithfrankish.com [email protected] Kavalas 10 Brain and Mind Programme 71307 Faculty of Medicine Heraklion, Crete P.O. Box 2208 Greece University of Crete +30-2810-236606 Heraklion 71003, Crete, Greece AREAS Specialisms: Philosophy of mind, philosophy of psychology, philosophy of cognitive science, Competences: Epistemology, philosophy of language, philosophical logic, metaphysics. EMPLOYMENT AND AFFILIATIONS 2017– UNIVERSITY OF SHEFFIELD, UK. Honorary Reader, Department of Philosophy (2017–). 1999 – THE OPEN UNIVERSITY, UK. Visiting Research Fellow (honorary), Department of Philosophy (2011–). Senior Lecturer (full-time, permanent), Department of Philosophy (2008–2011). Lecturer B (full-time, permanent), Department of Philosophy (2003–2008). Lecturer A (full-time, permanent), Department of Philosophy (1999–2003). 2008– UNIVERSITY OF CRETE, GREECE. Adjunct Professor (honorary, guest lecturer), Graduate Programme in the Brain and Mind Sciences, Faculty of Medicine (2010–). Visiting Researcher (0.5, fixed term), Department of Philosophy and Social Studies (2008– 2009). 2000–2003 UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE, UK, ROBINSON COLLEGE. Director of Studies in Philosophy (part-time) and undergraduate Supervisor in philosophy (occasional). 1995–1999 UNIVERSITY OF SHEFFIELD, UK. Teaching Assistant (part-time, fixed-term), Department of Philosophy (1998–1999). Temporary Lecturer (full time, fixed term), Department of Philosophy (1997). Tutor (part-time, fixed-term), Department of Philosophy (1995–1999). EDUCATION AND QUALIFICATIONS 1993–1999 UNIVERSITY OF SHEFFIELD. Ph.D. in Philosophy (passed viva, no changes required, July 2002; degree awarded January 2003). Thesis : ‘Mind and supermind: A two-level framework for folk psychology’. (Supervisors Peter Carruthers and Christopher Hookway.) M.A. in Philosophy (awarded 1996). With Distinction .