On the Cognitive Bases of Illusionism: an Untapped Tool for Brain and Behavioral Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF Version for Printing

Fermilab Today Thursday, March 27, 2008 Subscribe | Contact Fermilab Today | Archive | Classifieds Search Furlough Information Feature Fermilab Result of the Week Reminder: symmetry expands online Shedding new light An IDES representative will presence, features new blog on an old problem conduct the final on-site group meetings at 11 a.m. and noon in the Wilson Hall One West conference room on Friday, March 28. New furlough information, including an up-to-date Q&A section, appears on the furlough Web pages daily. symmetry magazine now provides more online content while it saves money by publishing fewer Layoff Information print issues. This figure shows the transverse photon New information on Fermilab From the symmetry editor: momentum in large extra dimension candidate layoffs, including an up-to-date events. The additional rate of signal events is This week's distribution of the new issue of Q&A section, appears on the shown in the open histogram along with the layoff Web pages daily. symmetry launches the next phase of the expected backgrounds. magazine's development. Our readers now Calendar use the magazine in different ways, and we When it comes to particle interactions, the are reaching a much larger audience. While force of gravity is an oddity. It is also entirely Thursday, March 27 readers are outspoken in wanting to keep the absent from the Standard Model theory. 10 a.m. print magazine, many of them are now more Although gravity is an undeniable force in our Presentations to the Physics comfortable reading online. everyday life and dominates interactions on the cosmological scale, it is by far the weakest Advisory Committee - Curia II Starting from this issue, we will publish six force at the particle level and has never been 1 p.m. -

John Nevil Maskelyne's Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee

JOHN NEVIL MASKELYNE’S QUEEN VICTORIA’S DIAMOND JUBILEE SPECULATION Courtesy The Magic Circle By Edwin A Dawes © Edwin A Dawes 2020 Dr Dawes first published this in the May, June and August 1992 issues of The Magic Circular, as part of his A Rich Cabinet of Magical Curiosities series. It is published here, with a few additions, on The Davenport Collection website www.davenportcollection.co.uk with the permission of The Magic Circle. 1 JOHN NEVIL MASKELYNE’S QUEEN VICTORIA’S DIAMOND JUBILEE SPECULATION John Nevil Maskelyne was well-known for his readiness, even eagerness, to embark upon litigation. There has always been the tacit assumption that, irrespective of the outcome, the ensuing publicity was considered good for business at the Egyptian Hall, and in later years at St. George’s Hall. In December 1897, however, Maskelyne was openly cited as an example of exploitation of the law of libel when a leader writer in The Times thundered “It was high time that some check should be put upon the recent developments of the law of libel as applied to public comment in the Press”. The paper’s criticism arose from three cases heard in the Queen’s Bench Division of the High Court of Justice on 16th December. One of these appeared under the heading of “MASKELYNE v. DIBBLEE AND OTHERS when Maskelyne sought to recover damages from the publisher and proprietors of the Manchester Guardian for alleged libel contained in an article which had appeared in their issue of 6th April, 1897. It is an interesting story, for which Queen Victoria’s long reign must be held responsible! The year 1897 marked the 60th anniversary of Queen Victoria’s accession, an occasion to be celebrated with full pomp and circumstance on 22nd June with a service of thanksgiving at St. -

Jon Racherbaumer There Are Not Many People Who Have Been

Anthony Darkstone In Conversation With ….. Jon Racherbaumer There are not many people who have been gifted with the skills of a brilliant writer. Even fewer people have the talent to write about magic and magicians. Jon Racherbaumer knows how to use words. He knows a great deal about magic and magicians. When it comes to writing about magic and magicians Jon Racherbaumer is the acknowledged leader. His name is well known to the magic world and hence also to the readers of The Linking Ring, m-u-m, Magic and Genii. He has written almost 70 books, and to date, well over a million meaningful words on magic. He has the unique ability and genius to make the esoteric understandable. He is, without any doubt, one of the most prolific writers on magic. With the excellent use of language and vocabulary he brings passion and value to our ancient art. I am honoured to be on the same Panel of Advisors with him on the magic web channel and it was a distinct honour for me to be on the close-up panel of judges with him at The Society of American Magicians 2001 convention in his home town of New Orleans. I am proud to be his friend and number 1 fan. I have had the privilege of spending fun times with Jon and I enjoy referring to him as The Thesaurus. He has always been a great source of inspiration to me and I'm indebted to him for several reasons – much too many to list. I am delighted & honored to share one of our many conversations. -

The Seance Free Download

THE SEANCE FREE DOWNLOAD John Harwood | 304 pages | 02 Apr 2009 | Vintage Publishing | 9780099516422 | English | London, United Kingdom The Seance The third point of view character is Eleanor Unwin, a young woman much like Constance with psychic powers that seem to want to destroy her. Sign In. By the end, it all made sense though. And The Seance Constance Langton has inherited this dark place as well The Seance the mysteries surrounding it. Get A Copy. Lucille Ball is actually a Leo. Sign In. External Sites. View Map View Map. Enter the The Seance as shown below:. Oh, how I worshipped at the alter of writers like Lowery Nixon Other editions. Lists with This Book. He came to our rescue many times. John Bosley : Angels. Meet your host, Anthony Host on Airbnb since See the full gallery. Clear your history. Sort order. In addition to communicating with the spirits of people who have a personal relationship to congregants, some Spiritual Churches also deal with spirits who may have a specific relationship to the medium or a historic relationship to the body of the church. The Seance entire novel reads like a prologue better off being cut: "I had hoped that Mama would The Seance content with regular messages from Alma but as the autumn advanced and the days grew shorter, the old haunted look crept back into her eyes The lawyer for the The Seance, John Montague, comes to find Constance and to tell her about the troubled history surrounding the Hall, and begs The Seance to The Seance the home once and for all. -

Just Deserts: the Dark Side of Moral Responsibility

(Un)just Deserts: The Dark Side of Moral Responsibility Gregg D. Caruso Corning Community College, SUNY What would be the consequence of embracing skepticism about free will and/or desert-based moral responsibility? What if we came to disbelieve in moral responsibility? What would this mean for our interpersonal re- lationships, society, morality, meaning, and the law? What would it do to our standing as human beings? Would it cause nihilism and despair as some maintain? Or perhaps increase anti-social behavior as some re- cent studies have suggested (Vohs and Schooler 2008; Baumeister, Masi- campo, and DeWall 2009)? Or would it rather have a humanizing effect on our practices and policies, freeing us from the negative effects of what Bruce Waller calls the “moral responsibility system” (2014, p. 4)? These questions are of profound pragmatic importance and should be of interest independent of the metaphysical debate over free will. As public procla- mations of skepticism continue to rise, and as the mass media continues to run headlines announcing free will and moral responsibility are illusions,1 we need to ask what effects this will have on the general public and what the responsibility is of professionals. In recent years a small industry has actually grown up around pre- cisely these questions. In the skeptical community, for example, a num- ber of different positions have been developed and advanced—including Saul Smilansky’s illusionism (2000), Thomas Nadelhoffer’s disillusionism (2011), Shaun Nichols’ anti-revolution (2007), and the optimistic skepti- cism of Derk Pereboom (2001, 2013a, 2013b), Bruce Waller (2011), Tam- ler Sommers (2005, 2007), and others. -

Downloadable and Ready Crucial to Our Understanding of What It Is to Be Physiology and Biophysics, and Director of the for Re-Use in Ways the Original Human

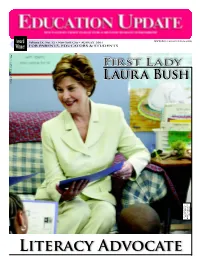

www.EDUCATIONUPDATE.com AwardAward Volume IX, No. 12 • New York City • AUGUST 2004 Winner FOR PARENTS, EDUCATORS & STUDENTS White House photo by Joyce Naltchayan First Lady Laura Bush U.S. POSTAGE PAID U.S. POSTAGE VOORHEES, NJ Permit No.500 PRSRT STD. PRSRT LITERACY ADVOCATE 2 SPOTLIGHT ON SCHOOLS ■ EDUCATION UPDATE ■ AUGUST 2004 Corporate Contributions to Education - Part I This Is The First In A Series On Corporate Contributions To Education, Interviewing Leaders Who Have Changed The Face Of Education In Our Nation DANIEL ROSE, CEO, ROSE ASSOCIATES FOCUSES ON HARLEM EDUCATIONAL ACTIVITIES FUND By JOAN BAUM, Ph.D. living in tough neighborhoods and wound up concentrating on “being effective at So what does a super-dynamic, impassioned, finding themselves in overcrowded the margin.” First HEAF took under its wing articulate humanitarian from a well known phil- classrooms. Of course, Rose is a real- the lowest-ranking public school in the city and anthropic family do when he becomes Chairman ist: He knows that the areas HEAF five years later moved it from having only 9 Emeritus, after having founded and funded a serves—Central Harlem, Washington percent of its students at grade level to 2/3rds. significant venture for educational reform? If Heights, the South Bronx—are rife Then HEAF turned its attention to a minority he’s Daniel Rose, of Rose Associates, Inc., he’s with conditions that all too easily school with 100 percent at or above grade level “bursting with pride” at having a distinguished breed negative peer pressure, poor but whose students were not successful in getting new team to whom he has passed the torch— self-esteem, and low aspirations and into the city’s premier public high schools. -

Biblioteca Digital De Cartomagia, Ilusionismo Y Prestidigitación

Biblioteca-Videoteca digital, cartomagia, ilusionismo, prestidigitación, juego de azar, Antonio Valero Perea. BIBLIOTECA / VIDEOTECA INDICE DE OBRAS POR TEMAS Adivinanzas-puzzles -- Magia anatómica Arte referido a los naipes -- Magia callejera -- Música -- Magia científica -- Pintura -- Matemagia Biografías de magos, tahúres y jugadores -- Magia cómica Cartomagia -- Magia con animales -- Barajas ordenadas -- Magia de lo extraño -- Cartomagia clásica -- Magia general -- Cartomagia matemática -- Magia infantil -- Cartomagia moderna -- Magia con papel -- Efectos -- Magia de escenario -- Mezclas -- Magia con fuego -- Principios matemáticos de cartomagia -- Magia levitación -- Taller cartomagia -- Magia negra -- Varios cartomagia -- Magia en idioma ruso Casino -- Magia restaurante -- Mezclas casino -- Revistas de magia -- Revistas casinos -- Técnicas escénicas Cerillas -- Teoría mágica Charla y dibujo Malabarismo Criptografía Mentalismo Globoflexia -- Cold reading Juego de azar en general -- Hipnosis -- Catálogos juego de azar -- Mind reading -- Economía del juego de azar -- Pseudohipnosis -- Historia del juego y de los naipes Origami -- Legislación sobre juego de azar Patentes relativas al juego y a la magia -- Legislación Casinos Programación -- Leyes del estado sobre juego Prestidigitación -- Informes sobre juego CNJ -- Anillas -- Informes sobre juego de azar -- Billetes -- Policial -- Bolas -- Ludopatía -- Botellas -- Sistemas de juego -- Cigarrillos -- Sociología del juego de azar -- Cubiletes -- Teoria de juegos -- Cuerdas -- Probabilidad -

Michael Vincent 22Nd February 2018

The Tapestry of Deception Michael Vincent 22nd February 2018 0:02:15 Academy Welcome 0:02:50 Lesson Introduc8on 0:09:00 Misdirec8on 0:12:15 The Tapestry of Decep8on 0:16:30 Overview 0:22:05 The Individual Threads of Magic 0:28:10 Strong Magic 0:46:25 Strong Effects 0:47:05 Mee8ng the Master - Slydini 0:49:50 Derek Dingle - Card under Glass 0:52:25 What is Misdirec8on? 0:54:30 Funner Color Stunner - Paul Harris/David Williamson 1:06:50 Alan Alan - “The Ini8a8on of Trains of Thought” 1:11:10 Fred Kaps - “I mis-direct even when I don’t need to” 1:16:40 Performing Context 1:21:45 Darwin Or8z 1:23:20 Sky Hooks - from John Ramsay’s Coins in the Hand rou8ne 1:37:45 Ques8on: How to stop the coins “talking” 1:40:55 Break (Ends: 1:42:15) 1:42:55 Ques8on: How does scrip8ng help with the clarity of the effect? 1:44:25 Ques8on: Do you have an example of a rou8ne that you know the audience will care about? 1:44:50 Smiling Mule - Roy Walton 1:53:35 Ques8on: Do you recommend any gaff coins for anyone not used to coin magic? 1:54:30 The Greatest Computer Ever Invented 2:00:30 The Ebb and Flow of Tension and Relaxa8on 2:04:40 Card under Glass - Loading the card - Derek Dingles handling of Larry Jenning’s Angle Steal 2:07:45 The Changeling 2:15:05 Two Card Monte 2:22:05 Recap of Bluff ShiI and Ultra move from The Changeling 2:23:20 Misdirec8on and physical technique 2:27:05 Tommy Tucker Pass 2:31:00 Applicaon 2:31:30 Signed Card to Sealed Envelope - Ron Wilson 2:46:20 The Signed Card - Brother John Hamman 2:55:10 Recap of the Angle Steal 2:59:10 Midnight ShiI -

1 Realism V Equilibrism About Philosophy* Daniel Stoljar, ANU 1

Realism v Equilibrism about Philosophy* Daniel Stoljar, ANU Abstract: According to the realist about philosophy, the goal of philosophy is to come to know the truth about philosophical questions; according to what Helen Beebee calls equilibrism, by contrast, the goal is rather to place one’s commitments in a coherent system. In this paper, I present a critique of equilibrism in the form Beebee defends it, paying particular attention to her suggestion that various meta-philosophical remarks made by David Lewis may be recruited to defend equilibrism. At the end of the paper, I point out that a realist about philosophy may also be a pluralist about philosophical culture, thus undermining one main motivation for equilibrism. 1. Realism about Philosophy What is the goal of philosophy? According to the realist, the goal is to come to know the truth about philosophical questions. Do we have free will? Are morality and rationality objective? Is consciousness a fundamental feature of the world? From a realist point of view, there are truths that answer these questions, and what we are trying to do in philosophy is to come to know these truths. Of course, nobody thinks it’s easy, or at least nobody should. Looking over the history of philosophy, some people (I won’t mention any names) seem to succumb to a kind of triumphalism. Perhaps a bit of logic or physics or psychology, or perhaps just a bit of clear thinking, is all you need to solve once and for all the problems philosophers are interested in. Whether those who apparently hold such views really do is a difficult question. -

21 Jan 2020 A) Tue, 21St Jan 2020 Lot 345

From the Curious to the Extraordinary (21 Jan 2020 A) Tue, 21st Jan 2020 Lot 345 Estimate: £400 - £600 + Fees MAGIC - MASKELYNE & COOKE, BERKELEY CASTLE, JANUARY 20TH 1870 In Honor of the Visit of His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales, Messrs. Maskelyne and Cooke the Celebrated Illusionists will appear as above in their new and original Entertainment, Entitled, A Grand Melange of Science and Mystery!! Mirthful and Inexplicable Wonders. Programme, Part One. An Exposition of Spiritual Manifestations, a la Daniel Home... , Nevil Maskelyne original decapitation scene... , an illustration of Chinese Jugglery... , original Transformation scene... Introducing the Mystic Freaks of Gyges! Or, the Monster Gorilla in his Enchanted Den, printed A. & J.T. Norman, Cheltenham, [1870?],. orig. souvenir programme printed in gilt on faded blue silk with decorative border, fringed braid with corner tassels 340mm x 260mm. John Nevil Maskelyne (1839-1917) was born in Cheltenham and descended from the astronomer royal Nevil Maskelyne. As a boy he was a keen amateur conjuror and in 1865 he exposed the famous spiritualists the Davenport brothers as imposters. This led Maskelyne and his friend George Alfred Cooke, a cabinet-maker, to embark on a joint career as professional magicians, their first appearance being at Jessop's Aviary Gardens, Cheltenham on 19th June 1865. They toured the provinces for eight years and eventually took a lease in the Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly where they successfully remained until the buildings demolition in 1904. Maskelyne was also an inventor taking out patents on numerous commercial inventions, including a cash register, a typewriter and his coin-operated lock for public lavatories (1892) which remained in use in England until the 1950s. -

Continuous Project #8 Table of Contents

Continuous Project #8 TABLE OF CONTENTS Continuous Project, Introduction 7 Continuous Project, CNEAI Exhibition, May 2006 8 Allen Ruppersberg, Metamorphosis: Patriote Palloy and Harry Houdini 11 Jacques Rancière, The Emancipated Spectator 19 Seth Price, Law Poem 31 Claire Fontaine, The Ready-Made Artist and Human Strike: A Few Clarifications 33 Dan Graham, Two-Way Mirror Cylinder inside Two-Way Mirror Cube; manuscript, contributed by Karen Kelly 45 Bettina Funcke, Urgency 53 Matthew Brannon, The last thing you remember was staring at the little white tile (Hers) and The last thing you remember was staring at the little white tile (His) 59 Alexander Kluge and Oskar Negt, The Public Sphere of Children 61 Mai-Thu Perret, Letter Home 67 Left Behind. A Continuous Project Symposium with Joshua Dubler 71 Tim Griffin, Rosters 79 August Bebel, Charles Fourier: His Life and His Theories 81 Maria Muhle, Equality and Public Realm according to Hannah Arendt 83 Pablo Lafuente, Image of the People, Voices of the People 91 Melanie Gilligan, The Emancipated – or Letters Not about Art 99 Simon Baier, Remarks on Installation 109 Donald Judd, ART AND INTERNATIONALISM. Prolegomena, contributed by Ei Arakawa 117 Mai-Thu Perret, Bake Sale 127 Nico Baumbach, Impure Ideas: On the Use of Badiou and Deleuze for Contemporary Film Theory 129 Serge Daney, In Stubborn Praise of Information 135 Johanna Burton, ‘Of Things Near at Hand,’ or Plumbing Cezanne’s Navel 139 Warren Niesluchowski, The Ars of Imperium 147 Summaries 158 6 CONTINOUS PROJEct #8 INTRODUctION 7 INTRODUCTION The Centre national de l’estampe et de l’art imprimé (CNEAI) invited us, as Continuous Project, to spend a month in Paris in the Spring of 2006 in order to realize a publication and an exhibition. -

How False Assumptions Still Haunt Theories of Consciousness

The Myth of When and Where: How False Assumptions Still Haunt Theories of Consciousness Sepehrdad Rahimian1 1 Department of Psychology, National Research University Higher School of Economics, Moscow, Russia * Correspondence: Sepehrdad Rahimian [email protected] Abstract Recent advances in Neural sciences have uncovered countless new facts about the brain. Although there is a plethora of theories of consciousness, it seems to some philosophers that there is still an explanatory gap when it comes to a scientific account of subjective experience. In what follows, I will argue why some of our more commonly acknowledged theories do not at all provide us with an account of subjective experience as they are built on false assumptions. These assumptions have led us into a state of cognitive dissonance between maintaining our standard scientific practices on one hand, and maintaining our folk notions on the other. I will then end by proposing Illusionism as the only option for a scientific investigation of consciousness and that even if ideas like panpsychism turn out to be holding the seemingly missing piece of the puzzle, the path to them must go through Illusionism. Keywords: Illusionism, Phenomenal consciousness, Predictive Processing, Consciousness, Cartesian Materialism, Unfolding argument 1. Introduction He once greeted me with the question: “Why do people say that it was natural to think that the sun went round the earth rather than that the earth turned on its axis?” I replied: “I suppose, because it looked as if the sun went round the earth.” “Well,” he asked, “what would it have looked like if it had looked as if the earth turned on its axis?” -Anscombe, G.E.M (1963), An introduction to Wittgenstein’s Tractatus In a 2011 paper, Anderson (2011) argued that different theories of attention suffer from somewhat arbitrary and often contradictory criteria for defining the term, rendering it more likely that we should be excluding the term “attention” from our scientific theories of the brain (Anderson, 2011).