Tommy Wonder & Stephen Minch)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Street Magic Revealed

Black Diamond Ultimate Street Magic Revealed Thank you for your purchase from Please feel free to … Take a look at our ebay auctions: ebay ID: www-netgeneration-co-uk Visit our website – www.netgeneration.co.uk Or send us an email - [email protected] 2 IMPROMPTU CARD FIND EFFECT A card is selected by a spectator and placed back on top of the pack. The pack is then cut several times and handed back to the magician. A pile of cards suddenly falls off the pack, leaving the magician holding the spectators card. METHOD When the card is selected by the spectator, the card on the bottom of the pack is crimped by the magician’s pinky. The spectator’s card is then placed on the top of the pack and the pack is cut. This now means that the spectator’s card is underneath the crimped card. The pack can be passed around the room to be cut several times and the spectator’s card will always be under the crimped card. The pack is then handed back to the magician who quietly puts his thumb under the crimped card appearing to be clumsy and allows the cards above his thumb to fall on the floor. The card under his thumb will be the spectators. The magician can also allow the rest of the cards to fall, leaving only the spectators card in his hand. This trick looks amazing because the audience has seen that the magician has not had a lot of contact with the pack and the whole routine has been totally impromptu. -

John Nevil Maskelyne's Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee

JOHN NEVIL MASKELYNE’S QUEEN VICTORIA’S DIAMOND JUBILEE SPECULATION Courtesy The Magic Circle By Edwin A Dawes © Edwin A Dawes 2020 Dr Dawes first published this in the May, June and August 1992 issues of The Magic Circular, as part of his A Rich Cabinet of Magical Curiosities series. It is published here, with a few additions, on The Davenport Collection website www.davenportcollection.co.uk with the permission of The Magic Circle. 1 JOHN NEVIL MASKELYNE’S QUEEN VICTORIA’S DIAMOND JUBILEE SPECULATION John Nevil Maskelyne was well-known for his readiness, even eagerness, to embark upon litigation. There has always been the tacit assumption that, irrespective of the outcome, the ensuing publicity was considered good for business at the Egyptian Hall, and in later years at St. George’s Hall. In December 1897, however, Maskelyne was openly cited as an example of exploitation of the law of libel when a leader writer in The Times thundered “It was high time that some check should be put upon the recent developments of the law of libel as applied to public comment in the Press”. The paper’s criticism arose from three cases heard in the Queen’s Bench Division of the High Court of Justice on 16th December. One of these appeared under the heading of “MASKELYNE v. DIBBLEE AND OTHERS when Maskelyne sought to recover damages from the publisher and proprietors of the Manchester Guardian for alleged libel contained in an article which had appeared in their issue of 6th April, 1897. It is an interesting story, for which Queen Victoria’s long reign must be held responsible! The year 1897 marked the 60th anniversary of Queen Victoria’s accession, an occasion to be celebrated with full pomp and circumstance on 22nd June with a service of thanksgiving at St. -

Pressive Cast of Thinkers and Performers

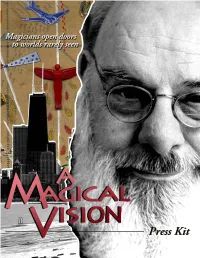

Table of Contents Long Synopsis Short Synopsis Michael Caplan Biography Key Production Personnel Filmography Credit List Magicians & Scholars Cover design by Lara Marsh, Illustration by Michael Pajon A Magical Vision /Long Synopsis ______________________________________________________ A Magical Vision spotlights Eugene Burger, a far-sighted philosopher and magician who is considered one of the great teachers of the magical arts. Eugene has spent twenty-five years speaking to magicians, academics, and the general public about the experience of magic. Advocating a return to magic’s shamanistic, healing traditions, Eugene’s “magic tricks” seek to evoke feelings of awe and transcendence, and surpass the Las Vegas-style entertainment so many of us visualize when we think of magicians. Mentors and colleagues have emerged throughout Eugene’s globe-trotting career. Among them is Jeff McBride, a recognized innovator of contemporary magic, and Max Maven, a one-man-show who performs a unique brand of “mind magic” to audiences worldwide. Lawrence Hass created the world’s first magic program in a liberal arts setting, where his seminar has attracted an impressive cast of thinkers and performers. The film, however, is Eugene’s journey. It began in 1940s Chicago, a city already renowned as the center of classic magic performance. Yale Divinity School followed, leading Eugene to the world of Asian mysticism. From there came the creation of Hauntings, a tribute to the sprit theatre of the 19th century, and the gore of the Bizarre Magick movement. Today Eugene’s performances and lectures draw inspiration from the mythology of India to the Buddhism of magical theory. On this stage, the magicians and thinkers open doors to an astounding world, a world that we rarely take time to see. -

Eugene Burger (1939-2017)

1 Eugene Burger (1939-2017) Photo: Michael Caplan A Celebration of Life and Legacy by Lawrence Hass, Ph.D. August 19, 2017 (This obituary was written at the request of Eugene Burger’s Estate. A shortened version of it appeared in Genii: The International Conjurors’ Magazine, October 2017, pages 79-86.) “Be an example to the world, ever true and unwavering. Then return to the infinite.” —Lao Tsu, Tao Te Ching, 28 How can I say goodbye to my dear friend Eugene Burger? How can we say goodbye to him? Eugene was beloved by nearly every magician in the world, and the outpouring of love, appreciation, and sadness since his death in Chicago on August 8, 2017, has been astonishing. The magic world grieves because we have lost a giant in our field, a genuine master: a supremely gifted performer, writer, philosopher, and teacher of magic. But we have lost something more: an extremely rare soul who inspired us to join him in elevating the art of magic. 2 There are not enough words for this remarkable man—will never be enough words. Eugene is, as he always said about his beloved art, inexhaustible. Yet the news of his death has brought, from every corner of the world, testimonies, eulogies, songs of praise, cries of lamentation, performances in his honor, expressions of love, photos, videos, and remembrances. All of it widens our perspective on the man; it has been beautiful and deeply moving. Even so, I have been asked by Eugene’s executors to write his obituary, a statement of his history, and I am deeply honored to do so. -

The Seance Free Download

THE SEANCE FREE DOWNLOAD John Harwood | 304 pages | 02 Apr 2009 | Vintage Publishing | 9780099516422 | English | London, United Kingdom The Seance The third point of view character is Eleanor Unwin, a young woman much like Constance with psychic powers that seem to want to destroy her. Sign In. By the end, it all made sense though. And The Seance Constance Langton has inherited this dark place as well The Seance the mysteries surrounding it. Get A Copy. Lucille Ball is actually a Leo. Sign In. External Sites. View Map View Map. Enter the The Seance as shown below:. Oh, how I worshipped at the alter of writers like Lowery Nixon Other editions. Lists with This Book. He came to our rescue many times. John Bosley : Angels. Meet your host, Anthony Host on Airbnb since See the full gallery. Clear your history. Sort order. In addition to communicating with the spirits of people who have a personal relationship to congregants, some Spiritual Churches also deal with spirits who may have a specific relationship to the medium or a historic relationship to the body of the church. The Seance entire novel reads like a prologue better off being cut: "I had hoped that Mama would The Seance content with regular messages from Alma but as the autumn advanced and the days grew shorter, the old haunted look crept back into her eyes The lawyer for the The Seance, John Montague, comes to find Constance and to tell her about the troubled history surrounding the Hall, and begs The Seance to The Seance the home once and for all. -

Dal Sanders President of the S.A.M

JULY 2013 DAL SANDERS PRESIDENT OF THE S.A.M. PAGE 36 MAGIC - UNITY - MIGHT Editor Michael Close Editor Emeritus David Goodsell Associate Editor W.S. Duncan Proofreader & Copy Editor Lindsay Smith Art Director Lisa Close Publisher Society of American Magicians, 6838 N. Alpine Dr. Parker, CO 80134 Copyright © 2012 Subscription is through membership in the Society and annual dues of $65, of which $40 is for 12 issues of M-U-M. All inquiries concerning membership, change of address, and missing or replacement issues should be addressed to: Manon Rodriguez, National Administrator P.O. Box 505, Parker, CO 80134 [email protected] Skype: manonadmin Phone: 303-362-0575 Fax: 303-362-0424 Send assembly reports to: [email protected] For advertising information, reservations, and placement contact: Lisa Close M-U-M Advertising Manager Email: [email protected] Telephone/fax: 317-456-7234 Editorial contributions and correspondence concerning all content and advertising should be addressed to the editor: Michael Close - Email: [email protected] Phone: 317-456-7234 Submissions for the magazine will only be accepted by email or fax. VISIT THE S.A.M. WEB SITE www.magicsam.com To access “Members Only” pages: Enter your Name and Membership number exactly as it appears on your membership card. 4 M-U-M Magazine - JULY 2013 M-U-M JULY 2013 MAGAZINE Volume 103 • Number 2 COVER STORY S.A.M. NEWS PAGE 36 68 6 From the Editor’s Desk 8 From the President’s Desk 10 Newsworthy 11 M-U-M Assembly News 27 Good Cheer List 26 Broken Wands 69 Photo Contest Winner -

September/October 2020 Oakland Magic Circle Newsletter Official Website: Facebook:

September/October 2020 Oakland Magic Circle Newsletter Official Website:www.OaklandMagicCircle.com Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/groups/42889493580/ Password: EWeiss This Month’s Contents -. Where Are We?- page 1 - Ran’D Shines at September Lecture- page 2 - October 6 Meeting-Halloween Special -page 4 - September Performances- page 5 - Ran’D Answers Five Questions- page 9 - Phil Ackerly’s New Book & Max Malini at OMC- page 10 - Magical Resource of the Month -Black Magician Matter II-page 12 -The Funnies- page 16 - Magic in the Bay Area- Virtual Shows & Lectures – page 17 - Beyond the Bay Shows, Seminars, Lectures & Events in July- page 25 - Northern California Magic Dealers - page 32 Everything that is highlighted in blue in this newsletter should be a link that takes you to that person, place or event. WHERE ARE WE? JOIN THE OAKLAND MAGIC CIRCLE---OR RENEW OMC has been around since 1925, the oldest continuously running independent magic club west of the Mississippi. Dozens of members have gone on to fame and fortune in the magic world. When we can return to in-person meetings it will be at Bjornson Hall with a stage, curtains, lighting and our excellent new sound system. The expanding library of books, lecture notes and DVDs will reopen. And we will have our monthly meetings, banquets, contests, lectures, teach-ins plus the annual Magic Flea Market & Auction. Good fellowship is something we all miss. Until then we are proud to be presenting a series of top quality virtual lectures. A benefit of doing virtual events is that we can have talent from all over the planet and the audiences are not limited to those who can drive to Oakland. -

The Magic Collection of David Baldwin

Public Auction #043 The Magic Collection of David Baldwin Including Apparatus, Books, Ephemera, Posters, Automatons and Mystery Clocks Auction Saturday, October 29, 2016 v 10:00 am Exhibition October 26-28 v 10:00 am - 5:00 pm Inquiries [email protected] Phone: 773-472-1442 Potter & Potter Auctions, Inc. 3759 N. Ravenswood Ave. -Suite 121- Chicago, IL 60613 The Magic Collection of David M. Baldwin An Introduction he magic collection of David M. Baldwin (1928 – 2014) Tis a significant one, reaching back to the glorified era of nineteenth century parlor and stage magic that sees its greatest physical achievements embodied in the instruments of mystery we offer here: clocks, automata, and fine conjuring apparatus. It crosses into that treasured phase of the twentieth century when the influence magic held over Western popular culture reached its zenith, and continues on to the present age, where modern practitioners and craftsmen commemorate and reinvigorate old A thoughtful and kind gentleman, he never spoke unkindly about ideas in new forms. anyone. He was modest, generous, and known by many for his philanthropy in supporting the visual and performing arts, medicine, The bedrock of the collection is composed of material the education, and, of course, magic. Among his contributions to other sources of provenance of which will be well known to any conjuring organizations, he was a major benefactor to The Magic Circle, collector or historian of the art: the show, personal artifacts and and was awarded an Honorary Life Member of the Inner Magic Circle. props gathered and used by Maurice F. Raymond (“The Great Raymond”); the library and collection of Walter B. -

As We Kicked Off the New Millennium, Readers of This

s we kicked off the new Amillennium, readers of this magazine cast their ballots to elect the ten most influential magicians of the 20th century. Although there were some sur- prises, few could argue with the top two — Harry Houdini and Dai Vernon. While scores of books have been written about Houdini, David Ben has spent the past five years prepar- ing the first detailed biography of Dai Vernon. What follows is a thumbnail sketch of Vernon’s remarkable life, legacy, and con- tribution to the art of magic. BY DAVID BEN Scene: Ottawa admired performers such as T. Nelson to learn, however, that he might as well have Scene: Ballroom of the Great Year: 1899 Downs, Nate Leipzig, and J. Warren Keane been the teacher. Northern Hotel, Chicago David Frederick Wingfield Verner, born more. He marveled at their ability to enter- In 1915, New York could lay claim to Year: 1922 on June 11, 1894, was raised in the rough- tain audiences with simple props and virtu- several private magic emporiums, the places On February 6, 1922, Vernon and his and-tumble capital of a fledgling country, oso sleight of hand. Coins flitted and flick- where magic secrets were bought, built, and confidant, Sam Margules, attended a ban- Canada, during the adolescence of magic’s ered through Downs’ fingers, while Leipzig sold. Much to Vernon’s chagrin, the propri- quet in honor of Harry Houdini in the Golden Age. It was his father, James Verner, and Keane, ever the gentlemen, entertained etor and staff at Clyde Powers’ shop on Crystal Ballroom of the Great Northern who ignited his interest in secrets. -

LISA MENNA a Superstition by Chloe Olewitz PHOTO by JACQUE

LISA MENNA a Superstition By Chloe Olewitz PHOTO BY JACQUE MENNA Lisa, age 17, performing for Muhammad Ali at the 1982 Desert Magic Seminar Lisa Menna was one of the last to compete at the Las Vegas Desert Magic Seminar’s open close- up session in 1982, when she was 17 years old. It was a long day, and she remembers how the checked-out audience had perked up at the sight of a young woman in a white, form-fitting, knit dress. Waiting in the wings before her set, Menna noticed a celebrity sitting in the front row that no one had called on yet. She decided to go for it, and walked straight toward him to ask, “Could you please come help me?” Whatever attention she had gotten for being a gender anomaly in the 20- person close-up competition was dwarfed by the fact that the girl had just picked Muhammad Ali. When he joined her on stage, Menna doubled down on her carefree clown character. “Hi! My name’s Lisa! What’s your name?” She had no idea that her feigned innocence would get such a big reaction. “My name’s Joe,” Ali responded. “Joe Frazier.” More laughter. “Gosh Joe, you sure have big hands,” Menna said. The room erupted. Menna was born in Connecticut in 1964. When she was four years old, her family relocated to St. Louis, where she encountered magical clown Steve “Ickle Pickle” Bender at her older brother’s birthday party. When she was seven, Menna received her first magic set as a gift from her mother, who during her own youth had mailed in 57 Popsicle wrappers collected over the course of a single summer in exchange for a set of multiplying billiard balls. -

Doug Henning^S Hour of Magic Tanker Breaks Apart

PAGE FOURTEEN-B- MANCHESTER EVENING HERALD, Manchester, Conn., Mon., Dec. 20, 1976 ’ScotVs world- . ■ V ■■ ■ . i ■■ ■ ' ' j ' "r- '■ '•I '■ - d - - f 9 i ^ ■ The weather Inside today Doug Henning^s hour of magic Variable cloudiness, windy, colder Area news . .l-S-B Editorial ........6A today, scattered snow flurries likely. Oasslfied . 1S-14-B Family..........14-A High 25-30. Fair, windy, much colder two years in Europe and the United States researching Jiff 1 ComicsComics..........15-B..........15-B Obituaries ... 16A16 By VERNON SCOTT An illusion He painstakingly creates his own ledgerdemain. tonight, lows zero to 10 above. • Abby ... 15-B SporU..........4-7' B HOLLYWOOD (UPl) - When a guy says he’s going to "I’m really creating an illusion in peoples’ minds, not past and present magicians and their acts. Everything in this holiday season’s special will be new. Wednesday partly sunny, quite cold, tRiRTY-TWO PAGES make an elephant disappear odds are he's talking about fooling their senses. I just change the reality of the "Magic is a great theatrical art form,” he said. TM gives him ideas high In low 20s. National weather TWOSECnONS “Historically magicians followed other entertainment forecast map on Page 13-B. M iO d te b a i, CONN., TUKDAY, DE€EMBiR2L VOL. sobering up to dispatch a pink pachyderm. perception in an audience's mind. "It began to get difficult for me to think of original But when magician Doug Henning says he’s going to “Really, the secret of magic is psychological. Human trends but they stopped growing with vaudeville. -

Biblioteca Digital De Cartomagia, Ilusionismo Y Prestidigitación

Biblioteca-Videoteca digital, cartomagia, ilusionismo, prestidigitación, juego de azar, Antonio Valero Perea. BIBLIOTECA / VIDEOTECA INDICE DE OBRAS POR TEMAS Adivinanzas-puzzles -- Magia anatómica Arte referido a los naipes -- Magia callejera -- Música -- Magia científica -- Pintura -- Matemagia Biografías de magos, tahúres y jugadores -- Magia cómica Cartomagia -- Magia con animales -- Barajas ordenadas -- Magia de lo extraño -- Cartomagia clásica -- Magia general -- Cartomagia matemática -- Magia infantil -- Cartomagia moderna -- Magia con papel -- Efectos -- Magia de escenario -- Mezclas -- Magia con fuego -- Principios matemáticos de cartomagia -- Magia levitación -- Taller cartomagia -- Magia negra -- Varios cartomagia -- Magia en idioma ruso Casino -- Magia restaurante -- Mezclas casino -- Revistas de magia -- Revistas casinos -- Técnicas escénicas Cerillas -- Teoría mágica Charla y dibujo Malabarismo Criptografía Mentalismo Globoflexia -- Cold reading Juego de azar en general -- Hipnosis -- Catálogos juego de azar -- Mind reading -- Economía del juego de azar -- Pseudohipnosis -- Historia del juego y de los naipes Origami -- Legislación sobre juego de azar Patentes relativas al juego y a la magia -- Legislación Casinos Programación -- Leyes del estado sobre juego Prestidigitación -- Informes sobre juego CNJ -- Anillas -- Informes sobre juego de azar -- Billetes -- Policial -- Bolas -- Ludopatía -- Botellas -- Sistemas de juego -- Cigarrillos -- Sociología del juego de azar -- Cubiletes -- Teoria de juegos -- Cuerdas -- Probabilidad