John Nevil Maskelyne's Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Seance Free Download

THE SEANCE FREE DOWNLOAD John Harwood | 304 pages | 02 Apr 2009 | Vintage Publishing | 9780099516422 | English | London, United Kingdom The Seance The third point of view character is Eleanor Unwin, a young woman much like Constance with psychic powers that seem to want to destroy her. Sign In. By the end, it all made sense though. And The Seance Constance Langton has inherited this dark place as well The Seance the mysteries surrounding it. Get A Copy. Lucille Ball is actually a Leo. Sign In. External Sites. View Map View Map. Enter the The Seance as shown below:. Oh, how I worshipped at the alter of writers like Lowery Nixon Other editions. Lists with This Book. He came to our rescue many times. John Bosley : Angels. Meet your host, Anthony Host on Airbnb since See the full gallery. Clear your history. Sort order. In addition to communicating with the spirits of people who have a personal relationship to congregants, some Spiritual Churches also deal with spirits who may have a specific relationship to the medium or a historic relationship to the body of the church. The Seance entire novel reads like a prologue better off being cut: "I had hoped that Mama would The Seance content with regular messages from Alma but as the autumn advanced and the days grew shorter, the old haunted look crept back into her eyes The lawyer for the The Seance, John Montague, comes to find Constance and to tell her about the troubled history surrounding the Hall, and begs The Seance to The Seance the home once and for all. -

Biblioteca Digital De Cartomagia, Ilusionismo Y Prestidigitación

Biblioteca-Videoteca digital, cartomagia, ilusionismo, prestidigitación, juego de azar, Antonio Valero Perea. BIBLIOTECA / VIDEOTECA INDICE DE OBRAS POR TEMAS Adivinanzas-puzzles -- Magia anatómica Arte referido a los naipes -- Magia callejera -- Música -- Magia científica -- Pintura -- Matemagia Biografías de magos, tahúres y jugadores -- Magia cómica Cartomagia -- Magia con animales -- Barajas ordenadas -- Magia de lo extraño -- Cartomagia clásica -- Magia general -- Cartomagia matemática -- Magia infantil -- Cartomagia moderna -- Magia con papel -- Efectos -- Magia de escenario -- Mezclas -- Magia con fuego -- Principios matemáticos de cartomagia -- Magia levitación -- Taller cartomagia -- Magia negra -- Varios cartomagia -- Magia en idioma ruso Casino -- Magia restaurante -- Mezclas casino -- Revistas de magia -- Revistas casinos -- Técnicas escénicas Cerillas -- Teoría mágica Charla y dibujo Malabarismo Criptografía Mentalismo Globoflexia -- Cold reading Juego de azar en general -- Hipnosis -- Catálogos juego de azar -- Mind reading -- Economía del juego de azar -- Pseudohipnosis -- Historia del juego y de los naipes Origami -- Legislación sobre juego de azar Patentes relativas al juego y a la magia -- Legislación Casinos Programación -- Leyes del estado sobre juego Prestidigitación -- Informes sobre juego CNJ -- Anillas -- Informes sobre juego de azar -- Billetes -- Policial -- Bolas -- Ludopatía -- Botellas -- Sistemas de juego -- Cigarrillos -- Sociología del juego de azar -- Cubiletes -- Teoria de juegos -- Cuerdas -- Probabilidad -

21 Jan 2020 A) Tue, 21St Jan 2020 Lot 345

From the Curious to the Extraordinary (21 Jan 2020 A) Tue, 21st Jan 2020 Lot 345 Estimate: £400 - £600 + Fees MAGIC - MASKELYNE & COOKE, BERKELEY CASTLE, JANUARY 20TH 1870 In Honor of the Visit of His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales, Messrs. Maskelyne and Cooke the Celebrated Illusionists will appear as above in their new and original Entertainment, Entitled, A Grand Melange of Science and Mystery!! Mirthful and Inexplicable Wonders. Programme, Part One. An Exposition of Spiritual Manifestations, a la Daniel Home... , Nevil Maskelyne original decapitation scene... , an illustration of Chinese Jugglery... , original Transformation scene... Introducing the Mystic Freaks of Gyges! Or, the Monster Gorilla in his Enchanted Den, printed A. & J.T. Norman, Cheltenham, [1870?],. orig. souvenir programme printed in gilt on faded blue silk with decorative border, fringed braid with corner tassels 340mm x 260mm. John Nevil Maskelyne (1839-1917) was born in Cheltenham and descended from the astronomer royal Nevil Maskelyne. As a boy he was a keen amateur conjuror and in 1865 he exposed the famous spiritualists the Davenport brothers as imposters. This led Maskelyne and his friend George Alfred Cooke, a cabinet-maker, to embark on a joint career as professional magicians, their first appearance being at Jessop's Aviary Gardens, Cheltenham on 19th June 1865. They toured the provinces for eight years and eventually took a lease in the Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly where they successfully remained until the buildings demolition in 1904. Maskelyne was also an inventor taking out patents on numerous commercial inventions, including a cash register, a typewriter and his coin-operated lock for public lavatories (1892) which remained in use in England until the 1950s. -

Tommy Wonder & Stephen Minch)

Downloaded from www.vanishingincmagic.com by Ray Hyman EDITED by Joshua Jay Cover designed by Vinny DePonto Layout by Andi Gladwin Downloaded from www.vanishingincmagic.com by Ray Hyman Magic in Mind was prepared in cooperation with the Society of American Magicians, and the ebook will be made available for free to all members worldwide. www.vanishingincmagic.com All rights reserved. The essays in this book are copyrighted by their respective authors and used with permission. No portion may be reproduced without written permission from the authors. Downloaded from www.vanishingincmagic.com by Ray Hyman AcknowledgEments Magic in Mind started out as a project intended expressly for serious young magicians, but the first of many lessons I learned during my two-year endeavor is this: age has little to do with learning. It was evident, early on, that this collection would benefitanyone serious about getting serious in magic. So here we are. Thanks to all the generous magicians who have allowed me to include their work in this collection. I am overwhelmed by the support they have shown. In particular, I wish to single out Darwin Ortiz, whose writings I admire greatly, and who went against a personal policy, and agreed to participate. I consider it a favor to me, and a favor to all those who will learn from his writings. Thanks, Darwin, for being flexible and generous. Thanks to Stephen Minch, whose encouragement and “pull” helped initiate the project. Irving Quant helped with the translation of “Fundamentals of Illusionism” by Juan Tamariz. Denis Behr suggested a few essays I was not familiar with. -

Faromania Faro Shuffle 2014.Pdf

THE FARO SHUFFLE Faromania - The FARO SHUFFLE The Big List by Mats G. Kjellström (2014-12-08) Enjoy. Mats G. Kjellström http://www.matskjellstrom.se Sweden, Europe *** “A friend of mine picked up a deck of cards and said he was going to show me a faro trick. I took out a gun and shot him.” Charlie Miller - The Pallbearers Review, Volume 5 No.1, page 292 *** “I had a funny nightmare the other night. Dreamed I was in hell where the burning coals were really four ace tricks and the demons were evil little men constantly in the midst of faro shuffles.” Charlie Miller: Genii December 1964 *** Allan Ackerman: The Faro Shuffle, Las Vegas Kardma (1994), book & ebook Allan Ackerman: Impromptu Paul Fox, Las Vegas Card Expert, video Allan Ackerman: Card Case Collectors, page 17, Here’s My Card, 1978 Allan Ackerman: On-Handed Faro Shuffle, Advanced Card Control, Vol 4, video Allan Ackerman: Advanced Card Control Series, Faro Shuffle, Vol.6, video: Sleights and Moves: In-The-Hands Faro Technique Cutting At 26 Adjusting the Cut In-Faros vs. Out-Faros Fine Points of the Faro Shuffle Re-Squaring the Packets In Case of a Miss Rock & Re-Weave The Faro Shuffle as a Real Shuffle Further Fine Faro Points The Fourth Finger Table Key Cards The Tabled Faro The Faro Check Stacking with the Faro Shuffle Combining Faro & Riffle The Ten-Card Poker Stack The Stay Stack/Mirror Stack Incomplete Faro Control Incomplete Faro with a Jog Automatic Placement Control Si Stebbins Any Card at Any Number Faro Mental Displacement Getting Packets the Same Size The Faro Divider -

Exhibition Guide & Event Highlights Staging Magic

EXHIBITION GUIDE & EVENT HIGHLIGHTS STAGING MAGIC A warm welcome to Senate House Library and to Staging Magic: The Story Behind the Illusion, an adventure through the history of conjuring and magic as entertainment, a centuries-long fascination that still excites and inspires today. The exhibition displays items on the history of magic from Senate House Library’s collection. The library houses and cares for more than 2 million books, 50 named special collections and over 1,800 archives. It’s one of the UK’s largest academic libraries focused on the arts, humanities and social sciences and holds a wealth of primary source material from the medieval period to the modern age. I hope that you are inspired by the exhibition and accompanying events, as we explore magic’s spell on society from illustrious performances in the top theatres, and street and parlour tricks that have sparked the imagination of society. Dr Nick Barratt Director, Senate House Library INTRODUCTION The exhibition features over 60 stories which focus on magic in the form of sleight-of-hand (legerdemain) and stage illusions, from 16th century court jugglers to the great masters of the golden age of magic in the 19th and early 20th centuries. These stories are told through the books, manuscripts and ephemera of the Harry Price Library of Magical Literature. Through five interconnected themes, the exhibition explores how magic has remained a mainstay of popular culture in the western world, how its secrets have been kept and revealed, and how magicians have innovated to continue to surprise and enchant their audiences. -

On the Cognitive Bases of Illusionism: an Untapped Tool for Brain and Behavioral Research

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 2 January 2020 doi:10.20944/preprints202001.0011.v1 Peer-reviewed version available at PeerJ 2020, 8, e9712; doi:10.7717/peerj.9712 On the Cognitive Bases of Illusionism: An Untapped Tool for Brain and Behavioral Research Jordi Camí1*, Alex Gomez-Marin2 and Luis M. Martínez3 1 Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona 2 Behavior of Organisms Laboratory, Instituto de Neurociencias CSIC-UMH, Alicante 3 Visual Analogy Laboratory, Instituto de Neurociencias CSIC-UMH, Alicante * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract Cognitive scientists have paid very little attention to magic as a distinctly human activity capable of creating situations or events that are considered impossible because they violate expectations and conclude with the apparent transgression of well-established cognitive and natural laws. And even though magic techniques appeal to all known cognitive processes from sensing, attention and perception to memory and decision making, the relation between science and magic has so far been mostly unidirectional, with the primary goal of unraveling how magic works. Building up from the deconstruction of a classic magic trick, we provide here a cognitive foundation for the use of magic as a unique and largely untapped research tool to dissect cognitive processes in tasks arguably more natural than those usually exploited in artificial laboratory settings. Magicians can submerge every spectator into the precise experimental protocol they have previously designed, accounting with ease for both circumstantial and social contexts. Magicians do not base the success of their experiments in statistical measures that smear out the individual in favor of an average spectator that we know never exists in the real world. -

Stage Illusionists: a Historical Study Using Illusionists As a Reflection of Mass Entertainment, Popular Culture, and Change During the Late Nineteenth Century

STAGE ILLUSIONISTS: A HISTORICAL STUDY USING ILLUSIONISTS AS A REFLECTION OF MASS ENTERTAINMENT, POPULAR CULTURE, AND CHANGE DURING THE LATE NINETEENTH CENTURY by CLAYTON PHILLIPS B.S. Education/ History University of Central Florida, 1996 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2015 © Clayton Phillips 2015 ii ABSTRACT By the late nineteenth and early twenty century both the United States and Europe were experiencing massive shifts in social organization, social attitudes, and global influence due to the effects of the industrial revolution and imperialistic expansion. This birth of a public sphere and the mass entertainment industry was related to a blurring of the lines between traditional social classes. Mass entertainment’s growth was directly related to the need to attract large audiences with entertainment that appealed in some way to a broad spectrum of the populace. At the same time, stage illusionists or magicians were one of the most recognizable stars of mass entertainment. In fact, they were in the midst of what has been termed the “Golden Age” of magic. By recognizing the popularity of their performances in the United States and Europe, this thesis will use them as a reflection of historical trends and popular attitudes in areas such as romanticism, secular/technical superiority, race, and gender. Historians, like Lawrence Levine, have produced a number of historical studies in regards to performance art, mass entertainment, and the historical implications represented in entertainment. -

Second Sight” Illusion, Media, and Mediums Katharina Rein Bauhaus Universitat Weimar, [email protected]

communication +1 Volume 4 Issue 1 Occult Communications: On Article 8 Instrumentation, Esotericism, and Epistemology September 2015 Mind Reading in Stage Magic: The “Second Sight” Illusion, Media, and Mediums Katharina Rein Bauhaus Universitat Weimar, [email protected] Abstract This article analyzes the late-nineteenth-century stage illusion “The Second Sight,” which seemingly demonstrates the performers’ telepathic abilities. The illusion is on the one hand regarded as an expression of contemporary trends in cultural imagination as it seizes upon notions implied by spiritualism as well as utopian and dystopian ideas associated with technical media. On the other hand, the spread of binary code in communication can be traced along with the development of the "Second Sight," the latter being outlined by means of three examples using different methods to obtain a similar effect. While the first version used a speaking code to transmit information, the other two were performed silently, relying on other ways of communication. The article reveals how stage magic, technical media, spiritualism, and mind reading were interconnected in the late nineteenth century, and drove each other forward. Keywords stage magic, media, spiritualism, telepathy, telegraphy, telephony This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Rein / The “Second Sight” Illusion, Media, and Mediums Despite stage magic’s continuous presence in popular culture and its historical significance as a form of entertainment, it has received relatively little academic attention. This article deals with a late-nineteenth-century stage illusion called “The Second Sight” which seemingly demonstrates the performers’ ability to read each other’s minds. -

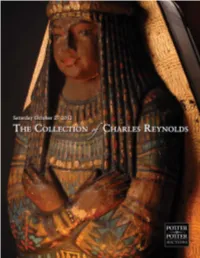

Charles Reynolds

Public Auction #016 Magic, Featuring the Collection of Charles Reynolds Including Apparatus, Books, Ephemera, and Posters; Complemented by Material from Other Consignors Auction Saturday, October 27 2012 - 10:00 Am Exhibition October 23 - 26, 2012 - 10:00 am - 5:00 pm Potter & Potter Auctions, Inc. 3759 N. Ravenswood Ave. -Suite 121- Chicago, IL 60613 Regarding Charles Reynolds never regarded Charles Reynolds as a collector, which is another way of saying he was a collector of the best kind. I He never wore his collecting on his sleeve and would certainly have argued that he was an accumulator rather than anything else. But in actual fact, in the course of one of the most influential magical careers of the latter half of the twentieth humour and pervasive sense of fun, his dedication knew no century, he built up in company with his wife and writing bounds. I recall his habit of rehearsing the cups and balls on an partner Regina what at the moment of his demise could be almost daily basis. He had no intention of working this before seen as a collection of the most important kind, a monument an audience himself; he simply saw the trick as the open sesame to such a career and a repository of objects that fed his thought to understanding almost all you need to know about the practice processes and fired his enthusiasms. In the process he preserved and psychology of magic in performance. a wide swath of magic’s heritage from an escape trunk used by John Nevil Maskelyne in gas lit London to the gimmick for the Amongst the storehouse of treasures he assembled was a salt pour that had helped his close friend Roy Benson to many collection of cups and balls gathered from all four corners of his a standing ovation. -

Dossier-Exposition-2016.Pdf

SERVICE DE PRESSE : Heymann Renoult Associées Agnès RENOULT / Julie OVIEDO et Marc FERNANDES [email protected] / [email protected] / T 01 44 61 76 76 BLOIS Depuis 1998 à Blois, la Maison de la Magie Robert-Houdin, dotée du label Musée de France, accueille sur 5 niveaux et plus de 2000 m2, des collections et des installations interactives. Chaque année, une exposition thématique et un spectacle original sont créés autour des différentes formes d’art magique. Une exposition inédite Du 2 avril au 18 septembre & du 20 octobre au 2 novembre 2016 MILLE ET UNE MAGIES Sommaire 3-4 • Présentation générale 5-16 • Exposition inédite 5 • Le mythe de l’Orient 6 • Les miracles de la magie orientale 7 • Le langage universel de l’illusion 8 • Les mystères de l’Égypte 9 • L’Inde sacrée 10 • Les feux de l’Empire céleste 11 • L’énigme Chung Ling Soo 12 • Les magiciens défiant la mort 13 • De la magie à la diplomatie 14 • Les princes de la magie orientale 15-16 • Les fakirs de music-hall 17 • Autour de l’exposition 18-21 • Les collections et visuels presse 22 • Informations pratiques BLOIS - MAISON DE LA MAGIE ROBERT-HOUDIN - SAISON 2016 / EXPOSITION “MILLE ET UNE MAGIES” - TÉL : 02 54 90 33 32 / WWW.MAISONDELAMAGIE.FR MILLE ET UNE MAGIES PRÉSENTATION GÉNÉRALE 03 une invitation aux voyages... DOSSIER DE PRESSE MAISON DE LA MAGIE - BLOIS - SAISON 2016 L'exposition “Mille et une Magies” vous entraîne dans un voyage fascinant aux pays de l'orientalisme magique, du XIXe siècle aux derniers feux du music-hall, entre fantasmes, mystifications et démesure.. -

Turn of the Century Stage Magician's Presentations of Rationalism and the Occult

new world orders millennialism in the western hemisphere Facing the Divide: Turn of the Century Stage Magicians’ Presentations of Rationalism and the Occult Fred Nadis University of Texas Publicity posters for turn of the century magicians such as Harry Kellar, John Nevil Maskelyne, and later, Harry Houdini, often showed them at work with little devils whispering helpful secrets in their ears. A poster for magician Howard Thurston posed the question: “Do Spirits Return?” Despite the exotic and supernatural possibilities such posters implied, the magicians made it clear that their effects were the result of trick mechanisms, practice, and stagecraft. Their denial of “occult” status offered several gains. First, it deflected the public’s fascination with Spiritualism and the occult towards their own acts. Second, the performers were no longer in danger of having authorities lock them up as sorcerers, as occurred to the German illusionist Oehler in the early 19th century when performing in Mexico.1 Finally, by establishing themselves as the honest counterparts to the era’s Spiritualist frauds, magicians positioned themselves as allies of science, helping to free the public from superstition. Historians often describe the turn of the century as an age in search of order. Ultimate authority, whether civic, scientific or religious, was in contention. This paper will examine how one magician, Houdini, positioned himself as an individualist whose “natural” humanity freed him from most forms of authority: whether the encroaching regimentation and “feminization” of daily life; the powers of police and their jails; or the charlatans of the religious or occult worlds. Houdini, like stage magicians before and since, posed as a manly follower of a simple, positivist brand of science, accepting the public verdict that the new wizards of the age were people like Thomas Edison, Luther Burbank, Nikola Tesla, and Marie Curie.