Imprima Este Artículo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Humanitarian Impact of Drones

THE HUMANITARIAN IMPACT OF DRONES The Humanitarian Impact of Drones 1 THE HUMANITARIAN IMPACT OF DRONES THE HUMANITARIAN IMPACT OF DRONES © 2017 Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom; International Contents Disarmament Institute, Pace University; Article 36. October 2017 The Humanitarian Impact of Drones 1st edition 160 pp 3 Preface Permission is granted for non-commercial reproduction, Cristof Heyns copying, distribution, and transmission of this publication or parts thereof so long as full credit is given to the 6 Introduction organisation and author; the text is not altered, Ray Acheson, Matthew Bolton, transformed, or built upon; and for any reuse or distribution, these terms are made clear to others. and Elizabeth Minor Edited by Ray Acheson, Matthew Bolton, Elizabeth Minor, and Allison Pytlak. Impacts Thank you to all authors for their contributions. 1. Humanitarian Harm This publication is supported in part by a grant from the 15 Foundation Open Society Institute in cooperation with the Jessica Purkiss and Jack Serle Human Rights Initiative of the Open Society Foundations. Cover photography: 24 Country case study: Yemen ©2017 Kristie L. Kulp Taha Yaseen 29 2. Environmental Harm Doug Weir and Elizabeth Minor 35 Country case study: Nigeria Joy Onyesoh 36 3. Psychological Harm Radidja Nemar 48 4. Harm to Global Peace and Security Chris Cole 58 Country case study: Djibouti Ray Acheson 64 Country case study: The Philippines Mitzi Austero and Alfredo Ferrariz Lubang 2 1 THE HUMANITARIAN IMPACT OF DRONES Preface Christof Heyns 68 5. Harm to Governmental It is not difficult to understand the appeal of Transparency Christof Heyns is Professor of Law at the armed drones to those engaged in war and other University of Pretoria. -

DOCUMENT RESUME Immigration and Ethnic Communities

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 413 156 RC 021 296 AUTHOR Rochin, Refugio I., Ed. TITLE Immigration and Ethnic Communities: A Focus on Latinos. INSTITUTION Michigan State Univ., East Lansing. Julian Samora Research Inst. ISBN ISBN-0-9650557-0-1 PUB DATE 1996-03-00 NOTE 139p.; Based on a conference held at the Julian Samora Research Institute (East Lansing, MI, April 28, 1995). For selected individual papers, see RC 021 297-301. PUB TYPE Books (010)-- Collected Works General (020) -- Information Analyses (070) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Demography; Elementary Secondary Education; Employment; Ethnic Bias; Hispanic Americans; *Immigrants; Immigration; *Labor Force; Mexican American Education; *Mexican Americans; Mexicans; Migrant Workers; Politics of Education; *Socioeconomic Status; Undocumented Immigrants IDENTIFIERS California; *Latinos; *Proposition 187 (California 1994); United States (Midwest) ABSTRACT For over a decade, Latino immigrants, especially those of Mexican origin, have been at the heart of the immigration debate and have borne the brunt of conservative populism. Contributing factors to the public reaction to immigrants in general and Latinos specifically include the sheer size of recent immigration, the increasing prevalence of Latinos in the work force, and the geographic concentration of Latinos in certain areas of the country. Based on a conference held at the Julian Samora Institute(Michigan) in April 1995, this book is organized around two main themes. The first discusses patterns of immigration and describes several immigrant communities in the United States; the second looks in depth at immigration issues, including economic impacts, employment, and provision of education and other services to immigrants. Papers and commentaries are: (1) "Introductory Statement" (Steven J. -

World Bank Document

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Social Inclusion in Uruguay Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized © 2020 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org This work was originally published by The World Bank in English as Social Inclusion in Uruguay, in 2020. In case of any discrepancies, the original language will prevail. This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this work is subject to copyright. Because The World Bank encourages dissemination of its knowledge, this work may be reproduced, in whole or in part, for noncommercial purposes as long as full attribution to this work is given. Attribution—The World Bank. 2020. Social Inclusion in Uruguay. Washington, DC: World Bank. License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO. Any queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to World Bank Publications, The World Bank Group, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA; fax: 202-522-2625; e mail: [email protected]. -

Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Distr

UNITED NATIONS CEDAW Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Distr. Women GENERAL CEDAW/C/SR.107 19 February 1988 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH COMMITTEE ON THE ELIMINATION OF DISCRIMINATION AGAINST WOMEN Seventh session SUMMARY RECORD OF THE 107th MEETING Held at Headquarters, New York, on Wednesday, 17 February 1988, at 3 p.m. Chairperson: Ms. BERNARD later: Ms. NOVIKOVA CONTENTS Consideration of reports submitted by States parties under article 18 of the Convention (continued) This record is subject to correction. Corrections should be submitted in one of the working languages. They should be set forth in a memorandum and also incorporated in a copy of the record. They should be sent within one ·.,eek of the date of this document to the Chief, Official Records Editing Section, Department of Conference Services, room DC2-750, 2 United Nations Plaza. Any corrections to the records of the meetings of this session will be consolidated in a single corrigendum, to be issued shortly after the end of the session. 88-55162 0016S (E) I ... CEDAW/C/SR.107 English Page 2 The meeting was called to order at 3.15 p.m. CONSIDERATION OF REPORTS SUBMITTED BY STATES PARTIES UNDER ARTICLE 18 OF THE CONVENTION (continued) Initial report of Uruguay (CEDAW/C/5/Add.27 and Amend.l) 1. At the invitation of the Chairperson, Ms. Giambruno (Uruguay) took a place at the Corranittee table. 2. Ms. GIAMBRUNO (Uruguay), introducing her country's initial report, said that the first section, prepared in November 1984, took a critical approach to the whole question of the situation of women in Uruguay. -

Latin American Book Store

Latin American P.O. Box 7328 Redlands CA 92375 Book Store Tel: 800-645-4276 Fax: 909-335-9945 www.latinamericanbooks.com [email protected] Women's Day Catalogue -- March 2018 1. Abril Stoffels, Ruth María (Dir.). MUJER E IGUALDAD: PARTICIPACIÓN POLÍTICA Y ERRADICACIÓN DE LA VIOLENCIA. Barcelona: Huygens Editorial (Colección LEX), 2015. 557p., facsimiles, tables, graphics, bibl., wrps. New . Paperback. ISBN: 9788415663461. "Mujer e igualdad: Participación política y erradicación de la violencia" analyzes the obstacles and discrimination women face in society, examining gender inequalities in education, economics, politics, experiences of violence, the labor market, leisure time, family obligations, participation in sports and more. This work especially focuses on two specific issues: political participation and violence against women, cross-analyzing these topics from various sociological, political and pedagogical perspectives. Contents include: "La labor de comité para la eliminación de la discriminación contra la mujer en la concreción del contenido de la convención sobre la eliminación de todas las formas de discriminación contra la mujer", "La acción positiva en materia electoral revisitada. Acción positiva, igualidad y elecciones: El artículo 44 bis de la loreg y la doctrina del tribunal constitucional", "La aplicación de la ley de igualdad (LO 3/2007) en las cortes", "Aspectos jurídicos y políticos de la violencia de género" and "La respuesta del derecho internacional público ante la violencia contra las mujeres y las niñas", among other chapters. (63248) $74.90 2. Alba Pagán, Ester; Beatriz Ginés Fuster and Luis Pérez Ochando (Eds.). DE-CONSTRUYENDO IDENTIDADES: LA IMAGEN DE LA MUJER DESDE LA MODERNIDAD. Valencia : Universitat de Valéncia, Departament d'História de lÁrt (Cuadernos Ars Longa, Número 6), 2016. -

V03N09-Worldview-Uruguay.Pdf

REACH PLANT TRAIN SERVE — SO ALL CAN HEAR T HI S I S S U E VOLU ME 3 — NU MBER 9 Ur u g u a y: B e a ut y B or n of Br o k e n n e s s Described by so me as a “ missionary graveyard of Latin 4 A m eri c a,” Ur u g u a y i s m o vi n g fr o m d ar k n e s s t o li g ht. B Y K RI S T E L O R TI Z Ur g e nt: Cri si s i n V e n e z u el a A G W M calls for special prayer as Venezuela continues 2 5 t o s e n d o ut mi s si o n ari e s i n t h e mi d st of t h e c o u ntr y’s w or st e c o n o mi c cri si s. B Y D A VI D E L LI S ‘ Pr e p ar e s Di o s A n g D a a n’ Russ Turney, retiring A G W M Asia Pacifc regional 2 6 dir e ct or, l o o k s b a c k o n 3 3 y e ar s i n w orl d mi s si o n s. B Y R U S S T U R N E Y W a yl ai d: H o w T w o B a n dit s M et C hri st When t wo Togolese robbers captured a missionary at 2 8 gunpoint, they met So meone else along a dark forest road. -

Imagining the Afro-Uruguayan Conventillo: Belonging and the Fetish of Place and Blackness

Imagining the Afro-Uruguayan Conventillo: Belonging and the Fetish of Place and Blackness by Vannina Sztainbok A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Sociology and Equity Studies in Education Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto © Copyright by Vannina Sztainbok (2009) IMAGINING THE AFRO-URUGUAYAN CONVENTILLO: BELONGING AND THE FETISH OF PLACE AND BLACKNESS Vannina Sztainbok Doctor of Philosophy 2009 Sociology and Equity Studies in Education University of Toronto Abstract This thesis explores the symbolic place occupied by a racialized neighbourhood within the Uruguayan national imaginary. I study the conventillos (tenement buildings) of two traditionally Afro-Uruguayan neighbourhoods in Montevideo, Barrio Sur and Palermo. These neighbourhoods are considered the cradle of Afro-Uruguayan culture and identity. The conventillos have been immortalized in paintings, souvenirs, songs, and books. Over the years most of the residents were evicted due to demolitions, which peaked during Uruguay’s military dictatorship (1973-1984). I address the paradox of how a community can be materially marginalized, yet symbolically celebrated, a process that is evident in other American nations (Brazil, Colombia, etc.). I show how race, class, and gender are entangled in folkloric depictions of the conventillo to constitute a limited notion of blackness that naturalizes the relationship between Afro-Uruguayans, music, sexuality, and domestic work. The folklorization of the space and it residents is shown to be a “fetishization” which enhances the whiteness of the national identity, while confining the parameters of black citizenship and belonging. Utilizing a methodology that draws on cultural geography, critical race, postcolonial, and feminist theory, my dissertation analyzes the various ways that the Barrio Sur/Palermo conventillo has been imagined, represented, and experienced. -

8931-DOL Child Labor Comp

URUGUAY Government Policies and Programs to Eliminate the Worst Forms of Child Labor The Government of Uruguay is an associated country of ILO-IPEC.4525 In December 2000, the government cre- ated the National Committee for the Eradication of Child Labor (CETI).4526 CETI has developed a National Ac- tion Plan for 2003-2005 to combat child labor,4527 and, as part of this plan, the government has held seminars on Tthe problem, developed legal reform proposals, and tailored existing adult skills training programs towards parents of working children.4528 The Government of Uruguay has cooperated with ILO-IPEC, the other MERCOSUR governments, and the Government of Chile to develop a 2002-2004 regional plan to combat child labor.4529 The National Institute for Minors, which oversees government programs for children, heads the Interinstitutional Commission for the Prevention and Protection of Children against Sexual Exploitation. The Commission con- ducts research on the phenomenon and operates a toll-free phone number to connect victims with support ser- vices.4530 It also developed a national plan against commercial sexual exploitation of children that includes education programs.4531 The Institute collaborates with an NGO partner to provide parents of working children with monthly payments in exchange for regular class attendance by their children.4532 INAME also works with at-risk youth such as those living on the street and provides adolescents with work training.4533 The government collaborates with NGOs to fund the Child and Family Service Center Plan,4534 which provides after school recreational programs for children and special services for street children.4535 4525 ILO-IPEC, All About IPEC: Programme Countries, [online] [cited July 4, 2003]; available from http://www.ilo.org/public/english/standards/ ipec/about/countries/t_country.htm. -

Between the Economy and the Polity in the River Plate: Uruguay 1811-1890

UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 33 INSTITUTE OF LATIN AMERICAN STUDIES RESEARCH PAPERS Between the Economy and the Polity in the River Plate: Uruguay 1811-1890 Fernando Lopez-Alves BETWEEN THE ECONOMY AND THE POLITY IN THE RIVER PLATE: URUGUAY, 1811-1890 Fernando Lopez-Alves Institute of Latin American Studies 31 Tavistock Square London WC1H 9HA British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0 901145 89 0 ISSN 0957-7947 ® Institute of Latin American Studies University of London, 1993 CONTENTS Introduction 1 I. Uruguayan Democracy and its Interpreters 8 The Exceptional Country Thesis 8 White Europeans in a Land of Recent Settlement 15 Ideas and Political Organisations 17 Structural Factors and Uruguayan Development 20 II. Parties, War and the Military 24 The Artigas Revolution 30 The Guerra Grande and Revoluciones de Partido 35 III. Civilian Rule and the Military 42 IV. Political Institutions, the Fears of the Elite and the Mobilisation of the Rural Poor 53 V. The Weakness of the Conservative Coalition 60 VI. Conclusions 65 Appendix: Presidents of Uruguay, 1830-1907 71 Notes 72 Bibliography 92 Fernando Lopez-Alves is Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of California, Santa Barbara. He was an Honorary Research Fellow at the Institute of Latin American Studies in 1992-93. Acknowledgments Data for this publication were gathered during two visits to Uruguay (July- October 1987 and May-August 1990). Archival research was greatly facilitated by the personnel of the Biblioteca Nacional of Montevideo, in particular those in the Sala Uruguay. -

Uruguay MODERATE ADVANCEMENT

Uruguay MODERATE ADVANCEMENT In 2014, Uruguay made a moderate advancement in efforts to eliminate the worst forms of child labor. The Government expanded the National Action Plan to End Child Labor in Garbage Scavenging to include a study of adolescent work in agriculture in rural areas and established the Office of Rural Employment within the Ministry of Labor to work directly with rural communities. The Ministry of Labor hired 20 additional labor inspectors and the Ministry of Interior held a series of workshops to train police, immigration officials, prosecutors, and judges on human trafficking issues. However, children in Uruguay continue to engage in the worst forms of child labor in garbage scavenging and commercial sexual exploitation. The Government does not collect or publish information on the number of investigations, prosecutions, and convictions for labor and criminal law violations. Uruguay lacks a comprehensive national child labor policy, and programs to prevent and eliminate child labor are limited. I. PREVALENCE AND SECTORAL DISTRIBUTION OF CHILD LABOR Children in Uruguay are engaged in the worst forms of child labor, including in garbage scavenging and commercial sexual exploitation.(1-5) Table 1 provides key indicators on children’s work and education in Uruguay. Table 1. Statistics on Children’s Work and Education Figure 1. Working Children by Sector, Ages 5-14 Children Age Percent Working (% and population) 5-14 yrs. 6.1(31,955) Attending School (%) 5-14 yrs. 97.8 Agriculture 28.4% Combining Work and School (%) 7-14 yrs. 6.5 Services 59.1% Primary Completion Rate (%) 104.3 Industry Source for primary completion rate: Data from 2010, published by UNESCO Institute 12.5% for Statistics, 2015.(6) Source for all other data: Understanding Children’s Work Project’s analysis of statistics from Encuesta Nacional de Trabajo Infantil (MTI), 2009.(7) Based on a review of available information, Table 2 provides an overview of children’s work by sector and activity. -

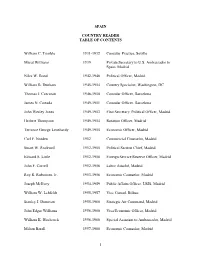

Table of Contents

SPAIN COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS William C. Trimble 1931-1932 Consular Practice, Seville Murat Williams 1939 Private Secretary to U.S. Ambassador to Spain, Madrid Niles W. Bond 1942-1946 Political Officer, Madrid William B. Dunham 1945-1954 Country Specialist, Washington, DC Thomas J. Corcoran 1948-1950 Consular Officer, Barcelona James N. Cortada 1949-1951 Consular Officer, Barcelona John Wesley Jones 1949-1953 First Secretary, Political Officer, Madrid Herbert Thompson 1949-1954 Rotation Officer, Madrid Terrence George Leonhardy 1949-1955 Economic Officer, Madrid Carl F. Norden 1952 Commercial Counselor, Madrid Stuart W. Rockwell 1952-1955 Political Section Chief, Madrid Edward S. Little 1952-1956 Foreign Service Reserve Officer, Madrid John F. Correll 1952-1956 Labor Attaché, Madrid Roy R. Rubottom, Jr. 1953-1956 Economic Counselor, Madrid Joseph McEvoy 1954-1959 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Madrid William W. Lehfeldt 1955-1957 Vice Consul, Bilbao Stanley J. Donovan 1955-1960 Strategic Air Command, Madrid John Edgar Williams 1956-1960 Visa/Economic Officer, Madrid William K. Hitchcock 1956-1960 Special Assistant to Ambassador, Madrid Milton Barall 1957-1960 Economic Counselor, Madrid 1 Harry Haven Kendall 1957-1961 Information Officer, USIS, Madrid Charles W. Grover 1958-1960 Vice Consul, Valencia Selwa Roosevelt 1958-1961 Spouse of Archie Roosevelt, Station Chief, Madrid Phillip W. Pillsbury, Jr. 1959-1960 Junior Officer Trainee, USIS, Madrid Frederick H. Sacksteder 1959-1961 Aide to Ambassador, Madrid Elinor Constable 1959-1961 Spouse of Peter Constable, Vice Consul, Vigo Peter Constable 1959-1961 Vice Consul, Vigo Allen C. Hansen 1959-1962 Assistant Cultural Affairs Officer, USIS, Madrid Frank Oram 1959-1962 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Madrid A. -

Descubrí Discover Descubra

descubrí discover descubra 2 3 This is an invitation to explore our city, to discover its landscape, whit its privileged position, be- tween the sea and the fertile land, to explore every inch of our streets and the harmony of our open spaces, the secrets of our architecture, the simbols of our history and culture. bienvenidos I have total confidence that, in Montevideo, you will meet with the warmth, respect and kindness of its people, as well as the dynamism of an active society building its future on the basis of shared aspirations. I am certain that you will find an increasingly safe city, which resolves its own conflicts bem-vindos of coexistence through dialogue and communication. Montevideo greets you with a warm embrace and the friendly manner of its citizens, the constant welcome improvement of its infrastructure and services, care for the environment and the strong commit- ment we have adopted, to make our city a true meeting-place. uero convidá-los a descobrirem e desfrutarem Montevidéu. Uma cidade em permanente uiero invitarlos a descubrir y disfrutar Montevideo. Una ciudad en permanente transforma- transformação que estreita laços com a região e com o mundo e desenvolve com firmeza a sua ción que estrecha lazos con la región y con el mundo y desarrolla con firmeza su vocación Qvocação integradora. Uma cidade humana, integrada a solidária que entre todos continuamos Qintegradora. construindo. Uma cidade que decide o presente com o olhar apontando para o futuro. Uma cidade Una ciudad humana, integrada y solidaria que entre todos seguimos construyendo. Una ciudad que que se abre ao país, à região e ao mundo, recebendo aqueles que nos visitam à procura de conhecer decide su presente con la mirada puesta en el futuro.