Youth Bilingualism, Identity and Quechua Language Planning And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ultimate Peru: Lima, Sacred Valley, Machu Picchu, Cuzco, and Lake Titicaca

9 Days/8 Nights Departs Daily from Lima Ultimate Peru: Lima, Sacred Valley, Machu Picchu, Cuzco, and Lake Titicaca Fascinating Peru – rich in culture, history, and natural beauty – is a country that has so much to offer. Consider this program a good introduction to Peru. It covers Lima, the Sacred Valley, Machu Picchu, Cuzco, and Lake Titicaca – all a must-see for any first-time visitor. If you have more time, we highly recommend extending your stay – add an extension to a jungle lodge; see the Nazca Lines; there is much more to see in this country of many contrasts. ACCOMMODATIONS •2 Nights Lima •1 Night Machu Picchu •2 Nights Cuzco •1 Night Sacred Valley with Dinner •2 Nights Puno INCLUSIONS •All Ground Transfers with •Pisac Market & Ollantaytambo •Cuzco City Tour and Ruins Vistadome Train to Machu Ruins Tour with Lunch •Uros and Taquile Islands Tour Picchu & Bus Ticket to Puno •2 Entrances to Machu Picchu & •Daily Breakfast •Lima City Tour 1 Guided Tour with Lunch ARRIVE LIMA: Begin your journey in Lima, Peru’s coastal capital city founded by the Spaniard Pizarro in 1535. Lima, with its historic buildings and museums, offers visitors an introduction to the colonial history of Peru. Airport greeting and transfer to Miraflores (suburb of Lima) to your selected hotel in the Miraflores neighborhood. (Accommodations, Lima) LIMA: After breakfast, you will be picked up for a city tour of Lima. The three-hour sightseeing tour offers the best of modern and colonial Lima. It includes visits to the Government Palace, The Plaza Mayor, City Hall, and the 17th-century San Francisco Monastery, followed by a drive through the modern neighborhood of San Isidro, with a stop at the pre-Inca pyramid of Huaca Huallamarca. -

Apus De Los Cuatro Suyos

! " " !# "$ ! %&' ()* ) "# + , - .//0 María Cleofé que es sangre, tierra y lenguaje. Silvia, Rodolfo, Hamilton Ernesto y Livia Rosa. A ÍNDICE Pág. Sumario 5 Introducción 7 I. PLANTEAMIENTO Y DISEÑO METODOLÓGICO 13 1.1 Aproximación al estado del arte 1.2 Planteamiento del problema 1.3 Propuesta metodológica para un nuevo acercamiento y análisis II. UN MODELO EXPLICATIVO SOBRE LA COSMOVISIÓN ANDINA 29 2.1 El ritmo cósmico o los ritmos de la naturaleza 2.2 La configuración del cosmos 2.3 El dominio del espacio 2.4 El ciclo productivo y el calendario festivo en los Andes 2.5 Los dioses montaña: intermediarios andinos III. LAS IDENTIDADES EN LOS MITOS DE APU AWSANGATE 57 3.1 Al pie del Awsangate 3.2 Awsangate refugio de wakas 3.3 De Awsangate a Qhoropuna: De los apus de origen al mundo de los muertos IV. PITUSIRAY Y EL TINKU SEXUAL: UNA CONJUNCIÓN SIMBÓLICA CON EL MUNDO DE LOS MUERTOS 93 4.1 El mito de las wakas Sawasiray y Pitusiray 4.2 El mito de Aqoytapia y Chukillanto 4.3 Los distintos modelos de la relación Sawasiray-Pitusiray 4.4 Pitusiray/ Chukillanto y los rituales del agua 4.5 Las relaciones urko-uma en el ciclo de Sawasiray-Pitusiray 4.6 Una homologación con el mito de Los Hermanos Ayar Anexos: El pastor Aqoytapia y la ñusta Chukillanto según Murúa El festival contemporáneo del Unu Urco o Unu Horqoy V. EL PODEROSO MALLMANYA DE LOS YANAWARAS Y QOTANIRAS 143 5.1 En los dominios de Mallmanya 5.2 Los atributos de Apu Mallmanya 5.3 Rivales y enemigos 5.4 Redes de solidaridad y alianzas VI. -

Viracocha 1 Viracocha

ווירָאקוצֱ'ה http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=37&ved=0COYCEBYwJA&url=http %3A%2F%2Fxa.yimg.com%2Fkq%2Fgroups%2F35127479%2F1278251593%2Fname%2F14_Ollantaytam bo_South_Peru.ppsx&ei=TZQaVK- 1HpavyASW14IY&usg=AFQjCNEHlXgmJslFl2wTClYsRMKzECmYCQ&sig2=rgfzPgv5EqG-IYhL5ZNvDA ויראקוצ'ה http://klasky-csupo.livejournal.com/354414.html https://he.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D7%A7%D7%95%D7%9F_%D7%98%D7%99%D7%A7%D7%99 ווירקוצ'ה فيراكوتشا http://www.startimes.com/?t=20560975 Viracocha 1 Viracocha Viracocha Great creator god in Inca mythology Offspring (according to some legends) Inti, Killa, Pachamama This article is about the Andean deity. For other uses, see Wiraqucha (disambiguation). Viracocha is the great creator god in the pre-Inca and Inca mythology in the Andes region of South America. Full name and some spelling alternatives are Wiracocha, Apu Qun Tiqsi Wiraqutra, and Con-Tici (also spelled Kon-Tiki) Viracocha. Viracocha was one of the most important deities in the Inca pantheon and seen as the creator of all things, or the substance from which all things are created, and intimately associated with the sea.[1] Viracocha created the universe, sun, moon, and stars, time (by commanding the sun to move over the sky) and civilization itself. Viracocha was worshipped as god of the sun and of storms. He was represented as wearing the sun for a crown, with thunderbolts in his hands, and tears descending from his eyes as rain. Cosmogony according to Spanish accounts According to a myth recorded by Juan de Betanzos,[2] Viracocha rose from Lake Titicaca (or sometimes the cave of Paqariq Tampu) during the time of darkness to bring forth light. -

Machu Picchu & the Sacred Valley

Machu Picchu & The Sacred Valley — Lima, Cusco, Machu Picchu, Sacred Valley of the Incas — TOUR DETAILS Machu Picchu & Highlights The Sacred Valley • Machu Picchu • Sacred Valley of the Incas • Price: $1,995 USD • Vistadome Train Ride, Andes Mountains • Discounts: • Ollantaytambo • 5% - Returning Volant Customer • Saqsaywaman • Duration: 9 days • Tambomachay • Date: Feb. 19-27, 2018 • Ruins of Moray • Difficulty: Easy • Urumbamba River • Aguas Calientes • Temple of the Sun and Qorikancha Inclusions • Cusco, 16th century Spanish Culture • All internal flights (while on tour) • Lima, Historic Old Town • All scheduled accommodations (2-3 star) • All scheduled meals Exclusions • Transportation throughout tour • International airfare (to and from Lima, Peru) • Airport transfers • Entrance fees to museums and other attractions • Machu Picchu entrance fee not listed in inclusions • Vistadome Train Ride, Peru Rail • Personal items: Laundry, shopping, etc. • Personal guide ITINERARY Machu Picchu & The Sacred Valley - 9 Days / 8 Nights Itinerary - DAY ACTIVITY LOCATION - MEALS Lima, Peru • Arrive: Jorge Chavez International Airport (LIM), Lima, Peru 1 • Transfer to hotel • Miraflores and Pacific coast Dinner Lima, Peru • Tour Lima’s Historic District 2 • San Francisco Monastery & Catacombs, Plaza Mayor, Lima Cathedral, Government Palace Breakfast, Lunch, Dinner Ollyantaytambo, Sacred Valley • Morning flight to Cusco, The Sacred Valley of the Incas 3 • Inca ruins: Saqsaywaman, Rodadero, Puca Pucara, Tambomachay, Pisac • Overnight: Ollantaytambo, Sacred -

SACRED VALLEY SINGLETRACK | MULTI-DAY TOUR Details & Pricing 3 DAYS | TRAIL RATING – DIFFICULT |630 – 895 USD Per Rider

SACRED VALLEY SINGLETRACK | MULTI-DAY TOUR Details & Pricing 3 DAYS | TRAIL RATING – DIFFICULT |630 – 895 USD per rider HIGHLIGHTS_ DAY 1 Best of Lamay DAY 2 Huchuy Qosqo Inca DAY 3 Patacancha Enduro ✓ Start a ride at 14,375 ft Lamay is one of the sleepiest Fort Pack your pedaling legs. A flowy and often rocky Enduro ✓ 22,600 ft of descents towns in the Sacred Valley, yet Today’s ride features a 2,000 ft racecourse that descends from ✓ 57 miles of singletrack home to the rowdiest rides in climb to our summit! Ride to an the heights of the Patacancha ✓ Ancient 800-year-old trails all of South America! Shuttle immense fortress with the best Valley to the Inca town of ✓ Peru’s world-class food and ride 3 unreal singletracks views of The Sacred Valley. Ollantaytambo. Please brake and culture and finish the day in the guinea Enjoy barbecue and brews back for alpacas! Finish the day at ✓ Good times with a fun- pig capitol of the world! (Night: at the lodge. (Night: The Sacred our favorite local brewery. loving team of guides The Sacred Valley) Valley) (Night: Lodging Not Included) ✓ Charming lodging in The Dist: 26.0 mi 1,120 ft Dist: 13.5 mi 3,812 ft Dist: 17.8 mi 1,168 ft Sacred Valley 9,830 ft Max: 13,985 ft 6,719 ft Max: 14,160 ft 6,042 ft Max. 14,375 ft www.perubiking.com WHAT’S INCLUDED PRICING ✓ 2017 YT CAPRA AL Enduro Mountain Bike Rental All Multi-Day Rides are organized in private groups to assure ✓ Helmet, Knee & Elbow Pads, and Gloves the best experience for riders. -

The Global Charango

The Global Charango by Heather Horak A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music and Culture Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2020 Heather Horak i Abstract Has the charango, a folkloric instrument deeply rooted in South American contexts, “gone global”? If so, how has this impacted its music and meaning? The charango, a small and iconic guitar-like chordophone from Andes mountains areas, has circulated far beyond these homelands in the last fifty to seventy years. Yet it remains primarily tied to traditional and folkloric musics, despite its dispersion into new contexts. An important driver has been the international flow of pan-Andean music that had formative hubs in Central and Western Europe through transnational cosmopolitan processes in the 1970s and 1980s. Through ethnographies of twenty-eight diverse subjects living in European fields (in Austria, France, Belgium, Germany, Spain, Portugal, Switzerland, Croatia, and Iceland) I examine the dynamic intersections of the instrument in the contemporary musical and cultural lives of these Latin American and European players. Through their stories, I draw out the shifting discourses and projections of meaning that the charango has been given over time, including its real and imagined associations with indigineity from various positions. Initial chapters tie together relevant historical developments, discourses (including the “origins” debate) and vernacular associations as an informative backdrop to the collected ethnographies, which expose the fluidity of the instrument’s meaning that has been determined primarily by human proponents and their social (and political) processes. -

Performing Blackness in the Danza De Caporales

Roper, Danielle. 2019. Blackface at the Andean Fiesta: Performing Blackness in the Danza de Caporales. Latin American Research Review 54(2), pp. 381–397. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25222/larr.300 OTHER ARTS AND HUMANITIES Blackface at the Andean Fiesta: Performing Blackness in the Danza de Caporales Danielle Roper University of Chicago, US [email protected] This study assesses the deployment of blackface in a performance of the Danza de Caporales at La Fiesta de la Virgen de la Candelaria in Puno, Peru, by the performance troupe Sambos Illimani con Sentimiento y Devoción. Since blackface is so widely associated with the nineteenth- century US blackface minstrel tradition, this article develops the concept of “hemispheric blackface” to expand common understandings of the form. It historicizes Sambos’ deployment of blackface within an Andean performance tradition known as the Tundique, and then traces the way multiple hemispheric performance traditions can converge in a single blackface act. It underscores the amorphous nature of blackface itself and critically assesses its role in producing anti-blackness in the performance. Este ensayo analiza el uso de “blackface” (literalmente, cara negra: término que designa el uso de maquillaje negro cubriendo un rostro de piel más pálida) en la Danza de Caporales puesta en escena por el grupo Sambos Illimani con Sentimiento y Devoción que tuvo lugar en la fiesta de la Virgen de la Candelaria en Puno, Perú. Ya que el “blackface” es frecuentemente asociado a una tradición estadounidense del siglo XIX, este artículo desarrolla el concepto de “hemispheric blackface” (cara-negra hemisférica) para dar cuenta de elementos comunes en este género escénico. -

Andean Music, the Left and Pan-Americanism: the Early History

Andean Music, the Left, and Pan-Latin Americanism: The Early History1 Fernando Rios (University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign) In late 1967, future Nueva Canción (“New Song”) superstars Quilapayún debuted in Paris amid news of Che Guevara’s capture in Bolivia. The ensemble arrived in France with little fanfare. Quilapayún was not well-known at this time in Europe or even back home in Chile, but nonetheless the ensemble enjoyed a favorable reception in the French capital. Remembering their Paris debut, Quilapayún member Carrasco Pirard noted that “Latin American folklore was already well-known among French [university] students” by 1967 and that “our synthesis of kena and revolution had much success among our French friends who shared our political aspirations, wore beards, admired the Cuban Revolution and plotted against international capitalism” (Carrasco Pirard 1988: 124-125, my emphases). Six years later, General Augusto Pinochet’s bloody military coup marked the beginning of Quilapayún’s fifteen-year European exile along with that of fellow Nueva Canción exponents Inti-Illimani. With a pan-Latin Americanist repertory that prominently featured Andean genres and instruments, Quilapayún and Inti-Illimani were ever-present headliners at Leftist and anti-imperialist solidarity events worldwide throughout the 1970s and 1980s. Consequently both Chilean ensembles played an important role in the transnational diffusion of Andean folkloric music and contributed to its widespread association with Leftist politics. But, as Carrasco Pirard’s comment suggests, Andean folkloric music was popular in Europe before Pinochet’s coup exiled Quilapayún and Inti-Illimani in 1973, and by this time Andean music was already associated with the Left in the Old World. -

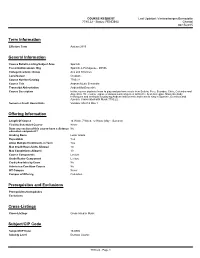

Spanish 7780.22 Revised 6-15-15.Pdf

COURSE REQUEST Last Updated: Vankeerbergen,Bernadette 7780.22 - Status: PENDING Chantal 06/15/2015 Term Information Effective Term Autumn 2015 General Information Course Bulletin Listing/Subject Area Spanish Fiscal Unit/Academic Org Spanish & Portuguese - D0596 College/Academic Group Arts and Sciences Level/Career Graduate Course Number/Catalog 7780.22 Course Title Andean Music Ensemble Transcript Abbreviation AndeanMusEnsemble Course Description In this course students learn to play and perform music from Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Chile, Colombia and Argentina. The course explores various musical genres within the Andean region. Students study techniques and methods for playing Andean instruments and learn to sing in Spanish, Quechua and Aymara. Cross-listed with Music 7780.22. Semester Credit Hours/Units Variable: Min 0.5 Max 1 Offering Information Length Of Course 14 Week, 7 Week, 12 Week (May + Summer) Flexibly Scheduled Course Never Does any section of this course have a distance No education component? Grading Basis Letter Grade Repeatable Yes Allow Multiple Enrollments in Term Yes Max Credit Hours/Units Allowed 10 Max Completions Allowed 10 Course Components Lecture Grade Roster Component Lecture Credit Available by Exam No Admission Condition Course No Off Campus Never Campus of Offering Columbus Prerequisites and Exclusions Prerequisites/Corequisites Exclusions Cross-Listings Cross-Listings Cross-listed in Music Subject/CIP Code Subject/CIP Code 16.0905 Subsidy Level Doctoral Course 7780.22 - Page 1 COURSE REQUEST Last Updated: Vankeerbergen,Bernadette 7780.22 - Status: PENDING Chantal 06/15/2015 Intended Rank Masters, Doctoral, Professional Requirement/Elective Designation The course is an elective (for this or other units) or is a service course for other units Course Details Course goals or learning • To become familiar with a range of Andean music genres through an applied approach to music performance. -

Ministerial Regional Meeting

MINISTERIAL REGIONAL MEETING “Education for All in Latin America and the Caribbean: Balance and Challenges post-2015” MINISTRY OF EDUCATION OF PERU Lima, October 30th and 31st, 2014 Education for All in Latin America and the Caribbean: Balance y Challenges post-2015 2 INDEX PRESENTATION 03 ORGANIZATION Organizers 04 Contacts 04 Participants 05 Venue of the Event 05 General Facilities 06 Visa 06 Health Services 06 Smokers 06 FACILITIES: Ministers 07 FACILITIES: Delegates and Technical Teams 08 GENERAL INFORMATION LIMA, Host City 14 Climate 15 Currency 15 Commerce 17 Telecommunications 17 Taxes 17 Electricity 17 Banks and Credit Card Services 17 Local Time 18 Attention Hours 18 Places of Interest 19 Gastronomy 22 Education for All in Latin America and the Caribbean: Balance y Challenges post-2015 3 PRESENTATION Education for All (EFA) was promoted by five multilateral organizations (UNESCO, UNICEF, UNDP, UNFPA and the World Bank) in the World Conference on Education for All held in Jomtien (1990) where it was assumed an “expanded vision of learning” and it was agreed to establish universal access to basic education and to massively reduce illiteracy before the end of the decade. This global commitment to provide quality basic education for all children, youth and adults was assumed by our country in the World Education Forum in Dakar (2000), where there were established six objectives aiming to meet the learning needs of all children, youth and adults by 2015. The priority activities of EFA are related to early childhood education, high quality universal primary education, education for youth and adults, literacy, gender equality and quality of education. -

Oxnard Course Outline

Course ID: MUS R109 Curriculum Committee Approval Date: 03/14/2018 Catalog Start Date: Fall 2019 COURSE OUTLINE OXNARD COLLEGE I. Course Identification and Justification: A. Proposed course id: MUS R109 Banner title: Music of Latin America Full title: Music of Latin America B. Reason(s) course is offered: This course would be a valuable addition to Oxnard College's offerings in humanities for transfer. It covers musical aesthetics, concepts, and history in a similar vein to History of Rock or Music Appreciation, but through a lens that is more attuned to OC's student demographics. It would also have the ability to span several disciplines, making it a fitting course for programs in Spanish, or perhaps Anthropology. This course is intended to satisfy CSU GE-Breadth area C1 and IGETC area 3A, and local GE in area C1 where comparable courses in music and art appreciation are approved. C. C-ID: 1. C-ID Descriptor: 2. C-ID Status: D. Co-listed as: Current: None II. Catalog Information: A. Units: Current: 3.00 B. Course Hours: 1. In-Class Contact Hours: Lecture: 52.5 Activity: 0 Lab: 0 2. Total In-Class Contact Hours: 52.5 3. Total Outside-of-Class Hours: 105 4. Total Student Learning Hours: 157.5 C. Prerequisites, Corequisites, Advisories, and Limitations on Enrollment: 1. Prerequisites Current: 2. Corequisites Current: 3. Advisories: Current: 4. Limitations on Enrollment: Current: D. Catalog description: Current: This course is a survey of the diverse and rich musical traditions of Latin America from pre-colonialism to the present day. The course will focus on the origins, influences, and styles within specific countries and regions such as Mexico, Brazil, the Andes, the Caribbean, the United States, and others. -

Emotion, Ethics and Intimate Spectacle in Peruvian Huayno Music

Andean Divas: Emotion, Ethics and Intimate Spectacle in Peruvian Huayno Music James Robert Butterworth Music Department Royal Holloway, University of London Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2014 1 Declaration of Authorship I, James Robert Butterworth, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: ________________________ Date: ________________________ 2 Abstract This thesis examines the self-fashioning and public images of star divas that perform Peruvian huayno music. These divas are both multi-authored stories about a person as well as actually existing individuals, occupying a space between myth and reality. I consider how huayno divas inhabit and perform a range of subject positions as well as how fans and detractors fashion their own sense of self in relation to such categories of experience. I argue that the ways in which divas and fans inhabit and reject different subject positions carry strong emotional and ethical implications. Combining multi-sited fieldwork in the music industry with analyses of songs, media representations and public discourses, I locate huayno divas in the context of Andean migration and attendant narratives about suffering, struggle, empowerment and success. I analyse huayno performances as intimate spectacles, which generate acts of both empathy and voyeurism towards the genre’s star performers (Chapter 2). The tales of romantic suffering and moral struggle contained in huayno songs, which provide a key source of audience engagement, are brought to life through the voices and bodies of huayno divas (Chapter 3).