The Global Charango

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Los Kjarkas Historia Jamás Contada

LOS KJARKAS: LA HISTORIA NO CONTADA LOS KJARKAS Actual formación de Los Kjarkas Introducción: Los más grandes de entre los grandes, los músicos andinos que han llevado al folklore latinoamericano a lo más alto, son sin duda alguna Los Kjarkas, un grupo que revolucionó el arte musical andino hace ya casi 50 años y que a lo largo de toda una vida nos han deleitado con impagables obras maestras con mayúsculas. Y es que todo en Los Kjarkas es grandioso: grandes músicos, grandes composiciones y una gran historia, por él han pasado intérpretes y compositores de gran calibre, manteniendo siempre un núcleo familiar en torno a la familia Hermosa. Sin embargo, no todo ha sido alegría, comprensión u honestidad dentro del grupo. En muchos foros, entrevistas o videos, se habla sobre la historia de los Kjarkas, pero se ha omitido gran parte de esta historia, historia que leerás hoy día. Es esta pues, la historia oculta de Los Kjarkas. LOS KJARKAS: LA HISTORIA NO CONTADA Advertencias: - Si eres una persona conservadora, un fanático a morir de Los Kjarkas, que los ve como “ídolos”, que no podrían hacer malo, y no deseas “tener” una mala imagen de ellos, te pido que dejes de leer este artículo, porque podrías cambiar de mirada y llevarte un gran disgusto. - Durante la historia, se nombrarán a otros grupos, que son necesarios de nombrar para poder entender la historia de Los Kjarkas. LOS KJARKAS: LA HISTORIA NO CONTADA Etimología del nombre: Sobre el nombre “Kjarkas” no hay nada dicho ciertamente. Se manejan dos significados y orígenes que se contradicen. -

Flutes, Festivities, and Fragmented Tradition: a Study of the Meaning of Music in Otavalo

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 4-2012 Flutes, Festivities, and Fragmented Tradition: A Study of the Meaning of Music in Otavalo Brenna C. Halpin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Ethnomusicology Commons Recommended Citation Halpin, Brenna C., "Flutes, Festivities, and Fragmented Tradition: A Study of the Meaning of Music in Otavalo" (2012). Master's Theses. 50. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/50 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. (/AV%\ C FLUTES, FESTIVITIES, AND FRAGMENTED TRADITION: A STUDY OF THE MEANING OF MUSIC IN OTAVALO by: Brenna C. Halpin A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty ofThe Graduate College in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the Degree ofMaster ofArts School ofMusic Advisor: Matthew Steel, Ph.D. Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan April 2012 THE GRADUATE COLLEGE WESTERN MICHIGAN UNIVERSITY KALAMAZOO, MICHIGAN Date February 29th, 2012 WE HEREBY APPROVE THE THESIS SUBMITTED BY Brenna C. Halpin ENTITLED Flutes, Festivities, and Fragmented Tradition: A Study of the Meaning of Music in Otavalo AS PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE Master of Arts DEGREE OF _rf (7,-0 School of Music (Department) Matthew Steel, Ph.D. Thesis Committee Chair Music (Program) Martha Councell-Vargas, D.M.A. Thesis Committee Member Ann Miles, Ph.D. Thesis Committee Member APPROVED Date .,hp\ Too* Dean of The Graduate College FLUTES, FESTIVITIES, AND FRAGMENTED TRADITION: A STUDY OF THE MEANING OF MUSIC IN OTAVALO Brenna C. -

WORKSHOP: Around the World in 30 Instruments Educator’S Guide [email protected]

WORKSHOP: Around The World In 30 Instruments Educator’s Guide www.4shillingsshort.com [email protected] AROUND THE WORLD IN 30 INSTRUMENTS A MULTI-CULTURAL EDUCATIONAL CONCERT for ALL AGES Four Shillings Short are the husband-wife duo of Aodh Og O’Tuama, from Cork, Ireland and Christy Martin, from San Diego, California. We have been touring in the United States and Ireland since 1997. We are multi-instrumentalists and vocalists who play a variety of musical styles on over 30 instruments from around the World. Around the World in 30 Instruments is a multi-cultural educational concert presenting Traditional music from Ireland, Scotland, England, Medieval & Renaissance Europe, the Americas and India on a variety of musical instruments including hammered & mountain dulcimer, mandolin, mandola, bouzouki, Medieval and Renaissance woodwinds, recorders, tinwhistles, banjo, North Indian Sitar, Medieval Psaltery, the Andean Charango, Irish Bodhran, African Doumbek, Spoons and vocals. Our program lasts 1 to 2 hours and is tailored to fit the audience and specific music educational curriculum where appropriate. We have performed for libraries, schools & museums all around the country and have presented in individual classrooms, full school assemblies, auditoriums and community rooms as well as smaller more intimate settings. During the program we introduce each instrument, talk about its history, introduce musical concepts and follow with a demonstration in the form of a song or an instrumental piece. Our main objective is to create an opportunity to expand people’s understanding of music through direct expe- rience of traditional folk and world music. ABOUT THE MUSICIANS: Aodh Og O’Tuama grew up in a family of poets, musicians and writers. -

C:\010 MWP-Sonderausgaben (C)\D

Dancando Lambada Hintergründe von S. Radic "Dançando Lambada" is a song of the French- Brazilian group Kaoma with the Brazilian singer Loalwa Braz. It was the second single from Kaomas debut album Worldbeat and followed the world hit "Lambada". Released in October 1989, the album peaked in 4th place in France, 6th in Switzerland and 11th in Ireland, but could not continue the success of the previous hit single. A dub version of "Lambada" was available on the 12" and CD maxi. In 1976 Aurino Quirino Gonçalves released a song under his Lambada-Original is the title of a million-seller stage name Pinduca under the title "Lambada of the international group Kaoma from 1989, (Sambão)" as the sixth title on his LP "No embalo which has triggered a dance wave with the of carimbó and sirimbó vol. 5". Another Brazilian dance of the same name. The song Lambada record entitled "Lambada das Quebradas" was is actually a plagiarism, because music and then released in 1978, and at the end of 1980 parts of the lyrics go back to the original title several dance halls were finally created in Rio de "Llorando se fue" ("Crying she went") of the Janeiro and other Brazilian cities under the name Bolivian folklore group Los Kjarkas from the "Lambateria". Márcia Ferreira then remembered Municipio Cochabamba. She had recorded this forgotten Bolivian song in 1986 and recorded the song composed by Ulises Hermosa and a legal Portuguese cover version for the Brazilian his brother Gonzalo Hermosa-Gonzalez, to market under the title Chorando se foi (same which they dance Saya in Bolivia, for their meaning as the Spanish original) with Portuguese 1981 LP Canto a la mujer de mi pueblo, text; but even this version remained without great released by EMI. -

2015 Review from the Director

2015 REVIEW From the Director I am often asked, “Where is the Center going?” Looking of our Smithsonian Capital Campaign goal of $4 million, forward to 2016, I am happy to share in the following and we plan to build on our cultural sustainability and pages several accomplishments from the past year that fundraising efforts in 2016. illustrate where we’re headed next. This year we invested in strengthening our research and At the top of my list of priorities for 2016 is strengthening outreach by publishing an astonishing 56 pieces, growing our two signatures programs, the Smithsonian Folklife our reputation for serious scholarship and expanding Festival and Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. For the our audience. We plan to expand on this work by hiring Festival, we are transitioning to a new funding model a curator with expertise in digital and emerging media and reorganizing to ensure the event enters its fiftieth and Latino culture in 2016. We also improved care for our anniversary year on a solid foundation. We embarked on collections by hiring two new staff archivists and stabilizing a search for a new director and curator of Smithsonian access to funds for our Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Folkways as Daniel Sheehy prepares for retirement, Collections. We are investing in deeper public engagement and we look forward to welcoming a new leader to the by embarking on a strategic communications planning Smithsonian’s nonprofit record label this year. While 2015 project, staffing communications work, and expanding our was a year of transition for both programs, I am confident digital offerings. -

HISPANIC MUSIC for BEGINNERS Terminology Hispanic Culture

HISPANIC MUSIC FOR BEGINNERS PETER KOLAR, World Library Publications Terminology Spanish vs. Hispanic; Latino, Latin-American, Spanish-speaking (El) español, (los) españoles, hispanos, latinos, latinoamericanos, habla-español, habla-hispana Hispanic culture • A melding of Spanish culture (from Spain) with that of the native Indian (maya, inca, aztec) Religion and faith • popular religiosity: día de los muertos (day of the dead), santería, being a guadalupano/a • “faith” as expession of nationalistic and cultural pride in addition to spirituality Diversity within Hispanic cultures Many regional, national, and cultural differences • Mexican (Southern, central, Northern, Eastern coastal) • Central America and South America — influence of Spanish, Portuguese • Caribbean — influence of African, Spanish, and indigenous cultures • Foods — as varied as the cultures and regions Spanish Language Basics • a, e, i, o, u — all pure vowels (pronounced ah, aey, ee, oh, oo) • single “r” vs. rolled “rr” (single r is pronouced like a d; double r = rolled) • “g” as “h” except before “u” • “v” pronounced as “b” (b like “burro” and v like “victor”) • “ll” and “y” as “j” (e.g. “yo” = “jo”) • the silent “h” • Elisions (spoken and sung) of vowels (e.g. Gloria a Dios, Padre Nuestro que estás, mi hijo) • Dipthongs pronounced as single syllables (e.g. Dios, Diego, comunión, eucaristía, tienda) • ch, ll, and rr considered one letter • Assigned gender to each noun • Stress: on first syllable in 2-syllable words (except if ending in “r,” “l,” or “d”) • Stress: on penultimate syllable in 3 or more syllables (except if ending in “r,” “l,” or “d”) Any word which doesn’t follow these stress rules carries an accent mark — é, á, í, ó, étc. -

3 AC 17-18 Music Master-18Pg

MUSIC TOURING ARTIST PERFORMANCES Adaawe Banana Slug String Band Adaawe is seven dynamic, diverse women who create The Banana Slug String Band fosters ecological rich, organic music of the voice and drum. Their music awareness, science education and positive human is an international fusion of African Diaspora music and interactions through music, theater, dance, puppetry rhythms. It is filled with celebration, inspiring and and student/teacher participation. Their hilarious and educational. The group has performed locally and high-energy shows have astounded thousands of nationally at colleges, schools, performing arts venues, children and teachers across the country since 1992. music festivals and community events. A spirit of Their music has been used in dozens of science curricula celebration and strength is the inspiration behind the and countless number of classrooms. So, join Airy group. Larry, Doug Dirt, Peter the Penguin, Professor Banana Slug and other special guests as they rock the earth with The show will take students on a trip to West Africa. science, song and sillybration! Each piece includes songs, dances, drumming and history. Children will sing, dance and play the In Living with the Earth, students discover the important instruments. They will learn African proverbs that they relationship between animals, plants and the Earth. can take with them and apply to their lives long after the Meet Slugo, our 6-foot-tall banana slug, learn how dirt performance. made your lunch and rap with Nature Man on this musical excursion. Travel with us through the habitats of coastal California Amy Knoles - Computer/Electronic Percussion in Awesome Ocean. -

Performing Blackness in the Danza De Caporales

Roper, Danielle. 2019. Blackface at the Andean Fiesta: Performing Blackness in the Danza de Caporales. Latin American Research Review 54(2), pp. 381–397. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25222/larr.300 OTHER ARTS AND HUMANITIES Blackface at the Andean Fiesta: Performing Blackness in the Danza de Caporales Danielle Roper University of Chicago, US [email protected] This study assesses the deployment of blackface in a performance of the Danza de Caporales at La Fiesta de la Virgen de la Candelaria in Puno, Peru, by the performance troupe Sambos Illimani con Sentimiento y Devoción. Since blackface is so widely associated with the nineteenth- century US blackface minstrel tradition, this article develops the concept of “hemispheric blackface” to expand common understandings of the form. It historicizes Sambos’ deployment of blackface within an Andean performance tradition known as the Tundique, and then traces the way multiple hemispheric performance traditions can converge in a single blackface act. It underscores the amorphous nature of blackface itself and critically assesses its role in producing anti-blackness in the performance. Este ensayo analiza el uso de “blackface” (literalmente, cara negra: término que designa el uso de maquillaje negro cubriendo un rostro de piel más pálida) en la Danza de Caporales puesta en escena por el grupo Sambos Illimani con Sentimiento y Devoción que tuvo lugar en la fiesta de la Virgen de la Candelaria en Puno, Perú. Ya que el “blackface” es frecuentemente asociado a una tradición estadounidense del siglo XIX, este artículo desarrolla el concepto de “hemispheric blackface” (cara-negra hemisférica) para dar cuenta de elementos comunes en este género escénico. -

Explorer's Guide Peruvian Music

EXPLORER’S GUIDE PERUVIAN MUSIC A shaman plays a flute alongside Amazonian Peru’s Boiling River. Facing the 1 2 3 4 Music in Hidden Workshop Andes Anthems Dinner and a Show Electric Inca Inside a storefront sign- Traditional Andean What originated as leftist, Follow up the show with Cusco posted simply “Luthier,” music isn’t something you anti-dictatorship music drinks and dancing at this expertly made Andean stumble across—it has to in the 1960s and ’70s has local staple for Andean While living among the instruments lie scattered be sought out. Wissler sug- morphed into Andean rock. Ukukus has live shows Q’eros, an indigenous around their maker. Sabino gests contacting Santos folk, supported by guitar, daily, while Sundays are Andean group in south- Huamán, a third-generation Machacca Apaza, a Q’ero, charango, various flutes, headlined by Amaru Puma east Peru, Holly Wissler stringed instrument crafts- to sit in on an offering to and drums. “People love it,” Kuntur, a band named for was immersed in their man, will demonstrate how apus (mountain gods) and says Wissler of the haunt- the three cosmic figures native music. Now based to play each charango, Pachamama (Mother Earth) ing melodies, which are of the Inca Empire (snake, in Cusco, the ethno- bandurria, guitar, and at his family’s home, 20 best enjoyed over dinner at puma, and condor). Here, musicologist and Nat quena flute. Ask to see his minutes outside Cusco. any number of restaurants folk music goes electric, Geo Expeditions expert workshop upstairs, says Request music up front so in Cusco, including the with hand pipes and quena outlines where to find Wissler—and even if you that his mother is around just opened Ayasqa, which flutes getting the rock- the best local beats. -

Andean Music, the Left and Pan-Americanism: the Early History

Andean Music, the Left, and Pan-Latin Americanism: The Early History1 Fernando Rios (University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign) In late 1967, future Nueva Canción (“New Song”) superstars Quilapayún debuted in Paris amid news of Che Guevara’s capture in Bolivia. The ensemble arrived in France with little fanfare. Quilapayún was not well-known at this time in Europe or even back home in Chile, but nonetheless the ensemble enjoyed a favorable reception in the French capital. Remembering their Paris debut, Quilapayún member Carrasco Pirard noted that “Latin American folklore was already well-known among French [university] students” by 1967 and that “our synthesis of kena and revolution had much success among our French friends who shared our political aspirations, wore beards, admired the Cuban Revolution and plotted against international capitalism” (Carrasco Pirard 1988: 124-125, my emphases). Six years later, General Augusto Pinochet’s bloody military coup marked the beginning of Quilapayún’s fifteen-year European exile along with that of fellow Nueva Canción exponents Inti-Illimani. With a pan-Latin Americanist repertory that prominently featured Andean genres and instruments, Quilapayún and Inti-Illimani were ever-present headliners at Leftist and anti-imperialist solidarity events worldwide throughout the 1970s and 1980s. Consequently both Chilean ensembles played an important role in the transnational diffusion of Andean folkloric music and contributed to its widespread association with Leftist politics. But, as Carrasco Pirard’s comment suggests, Andean folkloric music was popular in Europe before Pinochet’s coup exiled Quilapayún and Inti-Illimani in 1973, and by this time Andean music was already associated with the Left in the Old World. -

Spanish 7780.22 Revised 6-15-15.Pdf

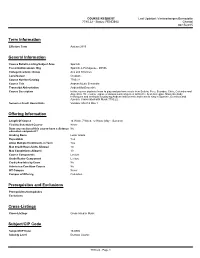

COURSE REQUEST Last Updated: Vankeerbergen,Bernadette 7780.22 - Status: PENDING Chantal 06/15/2015 Term Information Effective Term Autumn 2015 General Information Course Bulletin Listing/Subject Area Spanish Fiscal Unit/Academic Org Spanish & Portuguese - D0596 College/Academic Group Arts and Sciences Level/Career Graduate Course Number/Catalog 7780.22 Course Title Andean Music Ensemble Transcript Abbreviation AndeanMusEnsemble Course Description In this course students learn to play and perform music from Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Chile, Colombia and Argentina. The course explores various musical genres within the Andean region. Students study techniques and methods for playing Andean instruments and learn to sing in Spanish, Quechua and Aymara. Cross-listed with Music 7780.22. Semester Credit Hours/Units Variable: Min 0.5 Max 1 Offering Information Length Of Course 14 Week, 7 Week, 12 Week (May + Summer) Flexibly Scheduled Course Never Does any section of this course have a distance No education component? Grading Basis Letter Grade Repeatable Yes Allow Multiple Enrollments in Term Yes Max Credit Hours/Units Allowed 10 Max Completions Allowed 10 Course Components Lecture Grade Roster Component Lecture Credit Available by Exam No Admission Condition Course No Off Campus Never Campus of Offering Columbus Prerequisites and Exclusions Prerequisites/Corequisites Exclusions Cross-Listings Cross-Listings Cross-listed in Music Subject/CIP Code Subject/CIP Code 16.0905 Subsidy Level Doctoral Course 7780.22 - Page 1 COURSE REQUEST Last Updated: Vankeerbergen,Bernadette 7780.22 - Status: PENDING Chantal 06/15/2015 Intended Rank Masters, Doctoral, Professional Requirement/Elective Designation The course is an elective (for this or other units) or is a service course for other units Course Details Course goals or learning • To become familiar with a range of Andean music genres through an applied approach to music performance. -

Ministerial Regional Meeting

MINISTERIAL REGIONAL MEETING “Education for All in Latin America and the Caribbean: Balance and Challenges post-2015” MINISTRY OF EDUCATION OF PERU Lima, October 30th and 31st, 2014 Education for All in Latin America and the Caribbean: Balance y Challenges post-2015 2 INDEX PRESENTATION 03 ORGANIZATION Organizers 04 Contacts 04 Participants 05 Venue of the Event 05 General Facilities 06 Visa 06 Health Services 06 Smokers 06 FACILITIES: Ministers 07 FACILITIES: Delegates and Technical Teams 08 GENERAL INFORMATION LIMA, Host City 14 Climate 15 Currency 15 Commerce 17 Telecommunications 17 Taxes 17 Electricity 17 Banks and Credit Card Services 17 Local Time 18 Attention Hours 18 Places of Interest 19 Gastronomy 22 Education for All in Latin America and the Caribbean: Balance y Challenges post-2015 3 PRESENTATION Education for All (EFA) was promoted by five multilateral organizations (UNESCO, UNICEF, UNDP, UNFPA and the World Bank) in the World Conference on Education for All held in Jomtien (1990) where it was assumed an “expanded vision of learning” and it was agreed to establish universal access to basic education and to massively reduce illiteracy before the end of the decade. This global commitment to provide quality basic education for all children, youth and adults was assumed by our country in the World Education Forum in Dakar (2000), where there were established six objectives aiming to meet the learning needs of all children, youth and adults by 2015. The priority activities of EFA are related to early childhood education, high quality universal primary education, education for youth and adults, literacy, gender equality and quality of education.