The Status of the Camel in the United States of America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Pig out to Pig

unclean meats. Cornelius was a Gentile. Gentiles were animals were not created for food. like pigs to the Israelites, they were unclean. This How can I pray over a piece of unclean meat and make it Gentile loved the Hebrew God, prayed, and gave clean….its body chemistry did not change. God did not To Pig Out money to the poor. The Father wanted Cornelius to change. He did not make it clean just because I want it. Go know His Son Jesus, and to be filled with the Holy back to Is. 65 & 66 and remember the distaste that God Or Spirit. Therefore the vision: unclean animals which the Creator of all things, has for pig. Do you want to be the Father says; “Get up, Peter. Kill and smoke in the nostrils of God? I truly pray that many of eat.” (vs.10:13) Peters reply? “No Lord?” I have you will not just discard this pamphlet as trash, but will never eaten anything impure or unclean vs. 14. This honestly seek the Father’s Word for your answers, then To Opt Out story takes place years after the death of Jesus. Peter, show Him you love Him by keeping His commandments. by this statement is saying that the Food Laws were It is obedience that shows Him how much you trust Him never changed by Jesus. Then the Father speaks a to be true to His Word. For He alone protects it and will second time, “Do not call anything impure that God cause every Word to come to pass. -

THE CYPRUS QUESTION in the MAKING and the ATTITUDE of the SOVIET UNION TOWARDS the CYPRUS QUESTION (1960-1974) a Master's

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bilkent University Institutional Repository THE CYPRUS QUESTION IN THE MAKING AND THE ATTITUDE OF THE SOVIET UNION TOWARDS THE CYPRUS QUESTION (1960-1974) A Master’s Thesis by MUSTAFA ÇAĞATAY ASLAN DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS BILKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA September 2008 To my grandfathers Osman OYMAK and Mehmet Akif ASLAN, THE CYPRUS QUESTION IN THE MAKING AND THE ATTITUDE OF THE SOVIET UNION TOWARDS THE CYPRUS QUESTION (1960-1974) The Institute of Economics and Social Sciences of Bilkent University by MUSTAFA ÇAĞATAY ASLAN In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in THE DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS BILKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA September 2008 I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in International Relations. --------------------------- Associate Prof. Hakan Kırımlı Supervisor I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in International Relations. --------------------------- Assistant Prof. Dr. Nur Bilge Criss Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in International Relations. --------------------------- Assistant Prof. Dr. Eugenia Kermeli Examining Committee Member Approval of the Institute of Economics and Social Sciences --------------------------- Prof. Dr. Erdal Erel Director ABSTRACT THE CYPRUS QUESTION IN THE MAKING AND THE ATTITUDE OF THE SOVIET UNION TOWARDS THE CYPRUS QUESTION (1960-1974) Aslan, Mustafa Çağatay M.A., Department of International Relations Supervisor: Associate Prof. -

31 3 R -Ta.I¡¡V 25 Co ^ by 4^

C:9 238 Studies on Curing, Aging and_Smoking_of_Camel_Meat. II- Microbiological and Sensory Evaluation. E. T. EL-Asnwah, Salwa B. El-Magoli and M. M. Ibrahim. Dept, of Food. Sci. & Tech. Collage of Agric. Cairo University. Egypt. Introduction: Camel meat is considered as one of the toughest meat in Egypt. If camel meat could ^ plJt zed by aging, smoking and chill storage treatments while conserving other quality ritional attributes, its consumption would increase especially from elder animals. Meat structure can be considered in its simplest form to be a collection of p a rilieljher a ü ’' V^ the myofibrillar structure bound together by a connective tissue network of collQeI iCn » cot The physical properties of the myofibrillar fibers could be affected by (a) aging fit ns myofxhrillarmyofibrillar per se (.uavez(Davez andana Dickson,uicsson, i^/ui1970), , whilew u u e piuuuuxiiijproducing smallomaij. and^insig^^gonu 313fia comitant changes in the connective tissue (Bouton et al., 1973); (b) loss of molS.lit'-*1“ . ^ other changes produced by cooking (Bouton and Harris, 1972) and (c) increased^my contraction which increased muscle fiber diameter (Herring et al., 1967 b). The tissue would be affected by factors including: (a) changes in spatial orientation of collagen fibers in the connective tissue network related to myofibrillar- - - - - - contrac■ — ctr1^ _i ay. #i (Rowe, 1974) and (b) changes in the collagen produced by cooking and related to a . ifl / (Herring et al., 1967 a). Bouton et al., 1975 found that shear force values were n tegt3 _ ced by the muscle fiber properties than b'y the connective tissue properties, A}’ would be influenced by connective tissues as well as by the fiber properties. -

Ostrich Production Systems Part I: a Review

11111111111,- 1SSN 0254-6019 Ostrich production systems Food and Agriculture Organization of 111160mmi the United Natiorp str. ro ucti s ct1rns Part A review by Dr M.M. ,,hanawany International Consultant Part II Case studies by Dr John Dingle FAO Visiting Scientist Food and , Agriculture Organization of the ' United , Nations Ot,i1 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. M-21 ISBN 92-5-104300-0 Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without any prior written permission from the copyright holders provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the copyright holders. Applications for such permission, with a statement of the purpose and extent of the reproduction, should be addressed to the Director, Information Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Viale dells Terme di Caracalla, 00100 Rome, Italy. C) FAO 1999 Contents PART I - PRODUCTION SYSTEMS INTRODUCTION Chapter 1 ORIGIN AND EVOLUTION OF THE OSTRICH 5 Classification of the ostrich in the animal kingdom 5 Geographical distribution of ratites 8 Ostrich subspecies 10 The North -

Countries with Missing Data

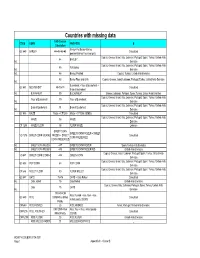

Countries with missing data FAO Code or CODE GEMS FAO FOOD B Calculation Barley+Pot Barley+Barley, GC 640 BARLEY 44+45+46+48 Calculated pearled+Barley Flour and grits Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Italy; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab 44 BARLEY Int. Emirates Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Italy; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab 45 Pot Barley Int. Emirates Int. 46 Barley, Pearled Cyprus; Turkey; United Arab Emirates 48 Barley Flour and Grits Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Lebanon; Portugal; Turkey; United Arab Emirates Int. Buckwheat + flour of buckwheat + GC 641 BUCKWHEAT 89+90+91 Calculated Bran of buckwheat Int. BUCKWHEAT 89 BUCKWHEAT Greece; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab Emirates Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Italy; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab Flour of Buckwheat 90 Flour of Buckwheat Int. Emirates Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Italy; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab Bran of Buckwheat 91 Bran of Buckwheat Int. Emirates GC 645 MAIZE Maize + CF1255 Maize + CF1255 (GEMS) Calculated Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Italy; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab MAIZE 56 MAIZE Emirates CF 1255 MAIZE FLOUR 58 FLOUR MAIZE Lebanon SWEET CORN SWEET CORN FROZEN + SWEET VO 1275 SWEET CORN (KERNEL FROZEN + SWEET Calculated CORN PRESERVED CORN PRESERVED Int. SWEET CORN FROZEN 447 SWEET CORN FROZEN Spain; United Arab Emirates Int. SWEET CORN PRESERV 448 SWEET CORN PRESERVED United Arab Emirates Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab VO 447 SWEET CORN (CORN-O 446 GREEN CORN Emirates Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Italy; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab GC 656 POP CORN 68 POP CORN Emirates Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Italy; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab CF 646 MILLET FLOUR 80 FLOUR MILLET Emirates GC 647 OATS 75+76 OATS + Oats Rolled Calculated Int. -

2017 Fall Edition

Oasis of Glenmont Cyprus Shriners Desert of New York FALL 2017 HAVING FUN. HELPING KIDS INSIDE THIS ISSUE POTENTATE’S MESSAGE 3 FALL CEREMONIAL 6 MEMBERSHIP 9 MILLION DOLLAR CLUB 13 CHIEF RABBAN’S MESSAGE 4 POTENTATE’S BALL 7 CHRISTMAS PARTY 10 UPCOMING EVENTS 14 www.cyprusshriners.com PAGE 2 CYPRUS NEWS Cyprus News Vote on proposed change to the By-Laws at Published Quarterly by Cyprus Shriners 9 Frontage Road, Glenmont, NY 12077 stated meeting Wednesday September 20, 2017 Tel: (518) 436-7892 Email: [email protected] ARTICLE V Website: www.cyprus5.org Initiation Fees, Dues, Per Capita, Hospital Levy Section 5.1 Initiation Fee The initiation fee shall 2017 Elected Divan be determined at a stated or special meeting of the Potentate Ill. Anthony T. Prizzia, Sr. (845) 691-2021 temple after notice has been given to each member [email protected] stating the proposed amount of the initiation fee. It Chief Rabban David M. Unser (518) 207-6711 must be paid in full prior to initiation. [email protected] Assistant Rabban Robert Baker (518) 857-8187 At this time the Fee for Initiation is $100.00, but [email protected] High Priest & Prophet John Donato (518) 479-0315 does not appear in the By Laws. [email protected] Oriental Guide Chris Wessell (518) 269-2262 We ask that the Initiation Fee be raised to $150.00. [email protected] Treasurer James H. Pulver (518) 326-1196 The reason for the increase is to provide every new [email protected] Noble with a Felt Embroidered Cyprus Fez at his Recorder Ill. -

Carpathian Journal of Food Science and Technology El

CARPATHIAN JOURNAL OF FOOD SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY journal homepage: http://chimie-biologie.ubm.ro/carpathian_journal/index.html EL KADID A TRADITIONAL SALTED DRIED CAMEL MEAT FROM ALGERIA: CONTRIBUTION TO THE STUDY OF THE COMPOSITION IN BIOGENIC AMINE, ORGANIC ACID, AROMATIC PROFILE AND MICROBIAL BIODIVERSITY Amina Bouchefra1,2*, Tayeb Idoui1,2, Chiara Montanari3 1Laboratory of Biotechnology, Environment and Health, University Mohamed Seddik Benyahia of Jijel,Ouled Aissa City, 18000 Algeria. 2Department of Applied Microbiology and Food Sciences, University Mohamed Seddik Benyahia of Jijel,Ouled Aissa City, 18000 Algeria. 3Centro Interdipartimentale di Ricerca Industriale Agroalimentare Universitàdegli Studi di Bologna Via Quinto Bucci 336 47521 Cesena (FC), Italy. *[email protected] https://doi.org/10.34302/crpjfst/2020.12.4.9 Article history: ABSTRACT Received: Many meat preparations are manufactured in North Africa.in Algeria, the 3 January 2020 dried salted camel meat is called El kadid. The first analysis of the Accepted: composition of biogenic amine, organic acid and aromatic profile of this 1 August 2020 traditional meat was carried out in this study. El kadid is obtained by salting, Keywords: maceration and drying of camel meat. The results showed that the product El kadid; contains lactic acid (6.22 g / kg), acetic acid (<1 g / kg). Biogenic amines Biogenic amine; are present at very low concentrations (<20 mg / kg). The aromatic profile Aromatic profile; highlighted the presence of more than 60 molecules belonging to different Organic acid; chemical classes, such as aldehydes, ketones and alcohols. El Kadid presente Biodiversity. has a rich microbiological niche (Enterobacteriaceae Latic acid bateria Coagulase negative microstaphylococci yeast, Enterococci and E coli). -

A. Answer the Questions. 1. Do People Live in the Desert?

K110a Reading 1-5 Exercise A. Answer the questions. 1. Do people live in the desert? Yes, they do. No, they don’t. 2. Is a desert hot at night? Yes, it’s hot at night. No, it’s cold at night. 3. Where do people sleep in a desert?(choose 2 answers) a. In a house. b. In a cactus. c. On a camel. d. In a tent. e. Next to a kangaroo. 4. Can you ride a camel? Yes, you can ride a camel. No, you can’t ride a camel. 5. What do goats have? a. They have milk, and meat. b. They have juice, and candy. c. They have a hump. 6. What do sheep have? a. They have milk, and meat. b. They have wool, and meat, c. They have wool, and milk. 7. What is a yak? a. A yak is a small desert plant. b. A yak is a tiny desert animal. c. A yak is a big desert animal. 8. Do you want to live in a desert? Why, or why not? K110a Reading 1-5 Exercise B. Choose the correct word to complete the story. house ride tent sleep goats sheep yaks carry In a desert some people live in a ________. In a desert some people live in a _____________ in a desert. Some people move around and __________ everywhere. They have camels. They use the camels to help them. The camels _______ things. They sometimes ______ the camel! They have _________ and ________, too. In a cold desert they have ________. -

Initial Layout

ison are wild animals. Although pearance of once numerous herds. A By 1888, when C. J. they are now raised commer- demand from the eastern United States Bcially—the Kansas Buffalo Asso- for bison products, both meat and hides, “Buffalo” Jones went ciation currently has 107 members raising coupled with the arrival in western Kan- 8,600 animals—bison do not have the sas of railroad lines that provided the searching in this region for same temperament as their domesticated means for cheaply and efficiently trans- cattle relatives. Bison, or buffalo, appear porting those products, led to a massive bison to capture alive, he docile when grazing and ruminating, but killing of bison. The killing was unregu- the mind behind the massive forehead and lated and thorough and was condoned by found a total of 37 animals. curved horns still thinks the way its an- the U.S. and state governments, anxious cestors thought. It is an animal that pre- to subdue free-roaming Indian tribes who and Bison athabascae), skeletal remains fers to run, but it is ready to fight when depended upon buffalo for food, materi- of extinct forms (such as Bison latifrons, threatened. als for shelter, and numerous other neces- Bison alleni, and Bison antiquus) can be Humans and bison have interacted sities, as well as for spiritual needs. recognized primarily by their continued for thousands of years in North America, Small remnant herds of bison remained diminution in overall size and smaller but that interaction until recent times has after the departure of the hide-hunters, horn cores, which also change in shape. -

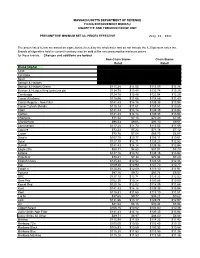

Cigarette Minimum Retail Price List

MASSACHUSETTS DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE FILING ENFORCEMENT BUREAU CIGARETTE AND TOBACCO EXCISE UNIT PRESUMPTIVE MINIMUM RETAIL PRICES EFFECTIVE July 26, 2021 The prices listed below are based on cigarettes delivered by the wholesaler and do not include the 6.25 percent sales tax. Brands of cigarettes held in current inventory may be sold at the new presumptive minimum prices for those brands. Changes and additions are bolded. Non-Chain Stores Chain Stores Retail Retail Brand (Alpha) Carton Pack Carton Pack 1839 $86.64 $8.66 $85.38 $8.54 1st Class $71.49 $7.15 $70.44 $7.04 Basic $122.21 $12.22 $120.41 $12.04 Benson & Hedges $136.55 $13.66 $134.54 $13.45 Benson & Hedges Green $115.28 $11.53 $113.59 $11.36 Benson & Hedges King (princess pk) $134.75 $13.48 $132.78 $13.28 Cambridge $124.78 $12.48 $122.94 $12.29 Camel All others $116.56 $11.66 $114.85 $11.49 Camel Regular - Non Filter $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Camel Turkish Blends $110.14 $11.01 $108.51 $10.85 Capri $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Carlton $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Checkers $71.54 $7.15 $70.49 $7.05 Chesterfield $96.53 $9.65 $95.10 $9.51 Commander $117.28 $11.73 $115.55 $11.56 Couture $72.23 $7.22 $71.16 $7.12 Crown $70.76 $7.08 $69.73 $6.97 Dave's $107.70 $10.77 $106.11 $10.61 Doral $127.10 $12.71 $125.23 $12.52 Dunhill $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Eagle 20's $88.31 $8.83 $87.01 $8.70 Eclipse $137.16 $13.72 $135.15 $13.52 Edgefield $73.41 $7.34 $72.34 $7.23 English Ovals $125.44 $12.54 $123.59 $12.36 Eve $109.30 $10.93 $107.70 $10.77 Export A $120.88 $12.09 $119.10 $11.91 -

Review Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-Cov)

Review Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV): A review Nour Ramadan1, Houssam Shaib2,* Abstract As a novel coronavirus first reported by Saudi Arabia in 2012, the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) is responsible for an acute human respiratory syndrome. The virus, of 2C beta- CoV lineage, expresses the dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4) receptor and is densely endemic in dromedary camels of East Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. MERS-CoV is zoonotic but human-to-human transmission is also possible. Surveillance and phylogenetic researches indicate MERS-CoV to be closely associated with bats’ coronaviruses, suggesting bats as reservoirs, although unconfirmed. With no vaccine currently available for MERS-CoV nor approved prophylactics, its global spread to over 25 countries with high fatalities highlights its role as ongoing public health threat. An articulated action plan ought to be taken, preferably from a One Health perspective, for appropriately advanced countermeasures against MERS-CoV. Keywords MERS-CoV, Lebanon, epidemiology, One Health. 3 Introduction1 with pneumonia and acute kidney injury. The June 19th, 2017, a case of Middle East virus was later isolated from the patient’s sputum. respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) is A different report appeared in September 2012, reported by the National International Health detecting a similar virus with 99.5% identity in a Regulation (IHR) focal point of Lebanon.1 As a previous patient who initially developed novel coronavirus, MERS-CoV was first symptoms in Qatar and had traveled to Saudi identified in a patient from the Kingdom of Arabia before the disease progression Saudi Arabia in June 2012 and was originally exacerbated.4 Seroepidemiologic and virologic named human coronavirus-EMC, as in Erasmus research revealed MERS-CoV infection in Medical Center.2 The case involved a man in dromedary camels (Camelus dromedarius) with Saudi Arabia who was admitted to the hospital isolated viruses from dromedaries competent in 5,6 infecting the human respiratory tract. -

Prospects for Rewilding with Camelids

Journal of Arid Environments 130 (2016) 54e61 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Arid Environments journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jaridenv Prospects for rewilding with camelids Meredith Root-Bernstein a, b, *, Jens-Christian Svenning a a Section for Ecoinformatics & Biodiversity, Department of Bioscience, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark b Institute for Ecology and Biodiversity, Santiago, Chile article info abstract Article history: The wild camelids wild Bactrian camel (Camelus ferus), guanaco (Lama guanicoe), and vicuna~ (Vicugna Received 12 August 2015 vicugna) as well as their domestic relatives llama (Lama glama), alpaca (Vicugna pacos), dromedary Received in revised form (Camelus dromedarius) and domestic Bactrian camel (Camelus bactrianus) may be good candidates for 20 November 2015 rewilding, either as proxy species for extinct camelids or other herbivores, or as reintroductions to their Accepted 23 March 2016 former ranges. Camels were among the first species recommended for Pleistocene rewilding. Camelids have been abundant and widely distributed since the mid-Cenozoic and were among the first species recommended for Pleistocene rewilding. They show a range of adaptations to dry and marginal habitats, keywords: Camelids and have been found in deserts, grasslands and savannas throughout paleohistory. Camelids have also Camel developed close relationships with pastoralist and farming cultures wherever they occur. We review the Guanaco evolutionary and paleoecological history of extinct and extant camelids, and then discuss their potential Llama ecological roles within rewilding projects for deserts, grasslands and savannas. The functional ecosystem Rewilding ecology of camelids has not been well researched, and we highlight functions that camelids are likely to Vicuna~ have, but which require further study.