THE CYPRUS QUESTION in the MAKING and the ATTITUDE of the SOVIET UNION TOWARDS the CYPRUS QUESTION (1960-1974) a Master's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neo-Kemalism Vs. Neo-Democrats?

' TURKISH FOREIGN POLICY BETWEEN 1960-1971: NEO-KEMALISM VS. NEO-DEMOCRATS? Sedat LAÇ 0NER ‘I hope you will understand that your NATO allies have not had a chance to consider whether they have an obligation to protect Turkey against the Soviet Union if Turkey takes a step which results in Soviet intervention without the full consent and understanding of its NATO allies.’ 1 Lyndon B. Johnson, US President, 1964 ‘Atatürk taught us realism and rationalism. He was not an ideologue.’ 2 Süleyman Demirel , Turkish Prime Minister Abstract In the post-coup years two main factors; the détente process, and as a result of the détente significant change in the United States’ policies towards Turkey, started a chain-reaction process in Turkish foreign policy. During the 1960s several factors forced Turkish policy makers towards a new foreign policy. On the one hand, the Western attitude undermined the Kemalist and other Westernist schools and caused an ideological transformation in Turkish foreign policy. On the other hand, the military coup and disintegration process that it triggered also played very important role in the foreign policy transformation process. Indeed, by undermining Westernism in Turkey, the West caused an ideological crisis in Kemalism and other foreign policy schools. The 1960s also witnessed the start of the disintegration process in Turkish politics that provided a suitable environment for the resurgence of the Ottoman schools of thought, such as Islamism and Turkism. 1 The Middle East Journal , Vol. 20, No. 3, Summer 1966, p. 387. 2 0hsan Sabri Ça /layangil, Anılarım, ( My Memoirs ), ( 0stanbul: Güne 2, 1990), p. -

Inönü Dönemi Türk Diş Politikasi

İNÖNÜ DÖNEM İ TÜRK DI Ş POL İTİKASI (TURKISH FOREIGN POLICY WITHIN THE PERIOD OF INONU) ∗ Ahmet İLYAS ** Orhan TURAN ÖZET İkinci Dünya Sava şı boyunca Türk dı ş politikasının genel e ğilimi sava şa girmeme üzerine kurulmu ştur. Türkiye’nin bu politikası sava şın gidi şatına göre de ğişiklikler göstermi ştir. Sava ş boyunca tarafsızlık politikası izleyen Türkiye, bu politikayı uygularken kimi zaman İngiltere ve Fransa’ya yakın olmasına kar şın Almanya’ya kar şı da net bir tavır almaktan kaçınmı ştır. Bu yüzden dı ş politika yapıcıları Türkiye’nin bu tavrını “ aktif tarafsızlık ” olarak nitelendirmektedirler. İngiltere, Fransa ve Rusya Türkiye’yi sava şa girmeye ikna etmek için birçok görü şmeler ve konferanslar yapmalarına ra ğmen; her defasında Türkiye sava ş dı şı kalmayı ba şarmı ştır. Ancak sava şın sonunun belli olmasından sonra Türkiye kazanan tarafta yer almak için sava şa girmi ştir. Sava ş sonrasında ise Türkiye, Sovyet Rusya’dan gelebilecek tehlikeyi bertaraf etmek için Batı kartını kullanarak ABD ve İngiltere taraflı bir politika izlemi ştir. Anahtar Kelimeler : İnönü, Türkiye, İngiltere, Sovyet Rusya, Almanya ABSTRACT During the World War II, the general inclination of Turkish foreign policy was based on an anti-war principle. This policy of Turkey changed according to the state of war. Following an objective policy during the war, Turkey avoided from developing a determined attitude towards Germany while it remained close to England and France. Therefore, foreign policy makers define this attitude of Turkey as active neutrality. Although England, France and Russia conducted negotiations and conferences to convince Turkey to take part in war, each time Turkey achieved to stand outside of the war. -

Presidential Elections in Cyprus in 2013

INTERNATIONAL POLICY ANALYSIS Presidential Elections in Cyprus in 2013 CHRISTOPHEROS CHRISTOPHOROU February 2013 n The right-wing party Democratic Rally is likely to return to power, twenty years since it first elected its founder, Glafcos Clerides, to the Presidency of the Republic of Cyprus and after ten years in opposition. The party’s leader may secure election in the first round, thanks to the alliance with the Democratic Party and the weakening of the governing communist Progressive Party of the Working People. n The economy displaced the Cyprus Problem as the central issue of the election cam- paign. The opposition blames the government’s inaction for the country’s ailing economy, while the government, the ruling AKEL and their candidate blame neolib- eral policies and the banking system. The candidate of the Social Democrats EDEK distinguishes himself by proposing to pre-sell hydrocarbons and do away with the Troika. He also openly opposes bizonality in a federal solution. n Whatever the outcome of the election, it will mark a new era in internal politics and in Cyprus’s relations with the European Union and the international community. The rapid weakening of the polarisation between left and right, at the expense of the left, may give rise to new forces. Their main feature is nationalist discourse and radical positions on the Cyprus Issue and other questions. Depending on the winner, Nicosia and Brussels may experience a kind of (their first) honeymoon or, conversely, a new period of strained relations. n At another level, the new President will have to govern under the scrutiny of the IMF and the European Union’s support mechanism. -

Turkey's Islamists: from Power-Sharing to Political

TURKEY’S ISLAMISTS: FROM POWER-SHARING TO POLITICAL INCUMBENCY The complex relationship between political Islam and the Turkish state – from political exclusion in the early Republican era, to power-sharing in the post-World War II multi-party era, to political incumbency in the 2000s – was crowned by AKP’s landslide electoral victory in 2002. The author debunks two myths regarding this relationship: first, that Kemalism enjoyed a monopoly of political power for decades and second, that Islamists achieved victory in 2002 after being the regime’s sole opposition. According to the author, Turkey’s failed Middle East policy can be attributed to AKP’s misconception that its Islamic counterparts would achieve power after the Arab uprisings just as they had done in Turkey in 2002. Behlül Özkan* Spring 2015 * Dr. Behlül Özkan is an Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science and International Relations at Marmara University, Istanbul. 71 VOLUME 14 NUMBER 1 BEHLÜL ÖZKAN he 1995 elections in Turkey, in which the Islamist Welfare Party (Refah Partisi) won the most votes, garnered much attention both in Turkey and abroad. Welfare Party leader Necmettin Erbakan took office as T prime minister the following year, the first time in the country’s histo- ry that an Islamist had occupied an executive position. Erbakan was subsequently forced out of office in the “post-modern coup” of 28 February 1997, widely inter- preted as a sign that achieving power by democratic means was still impossible for Islamists. Prominent Islamists such as current President and former Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan have often declared themselves to be the victims of the February 28 coup, which they cite as an instance of the perpetual repression faced by Islamists and their political constituencies since the founding of the Republic. -

Amerikan Belgelerinde 27 Mayis Olayi

AMERİKAN BELGELERİNDE 27 MAYİS OLAYİ Prof. Dr. FAHİR ARMAOĞLU 27 Mayıs askeri darbesinin, Cumhuriyet tarihimizde önemli ve ilginç bir yeri vardır. Olay, 1950'de gerçek anlamı ile işlemeye başlayan genç demok- rasimizin ilk "kesintisi" olduğu kadar, Büyük Atatürk'ün, Ordu ile Politika'yı birbirinden ayırdığı 1924 sonundan beri, Türk Silahlı Kuvvetleri'nin ilk defa olarak, bir siyasal olayın aktifunsuru haline gelmesidir. Ordunun, siyasal bir süreç içinde yer alması, 1961 Ekim seçimleriyle sona ermemiş, 1980 Eylülüne kadar devam eden dönemde, "Ordu faktörü", Türk iç politikasında bazan "silik", bazan da ön plâna çıkan bir nitelikte, yaklaşık 20 yıl kadar devam et- miştir. Bu belirttiğimiz noktalar, doğrudan doğruya Türkiye'nin kendi iç geliş- meleriyle ilgilidir. Fakat, 27 Mayıs Olayı' nın bir de dış politika yanı vardır. Başka bir deyişle, 27 Mayıs olayı, Türkiye'nin dış politikasına da yansıyacak nitelikte olmuştur. Şu anlamda ki, 27 Mayıs olayı meydana geldiğinde, Türk dış politikasında en etkin ve hatta dış politikamıza yön veren tek faktör, De- mokrat Parti hükümetlerinin izlediği dış politikanın doğal sonucu olarak, Amerika Birle şik Devletleri'dir. Aşağıda göreceğimiz gibi, 1960 Nisanından itibaren Türkiye'nin içi karıştığında, Demokrat Parti iktidarı, Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi'nin etkin muhalefeti ve kamuoyunun tepkileri karşısında, Ame- rika'da bir dayanak arama yoluna gitmiştir. Bu durum, Amerika'yı, bir hayli s ıkıntılı duruma itmiş görünüyor. Zira, Amerika'nın o zamanki Ankara Bü- yükelçisinin, 28 May ıs 1960 sabahı, darbenin liderliğini üzerine almış olan Orgeneral Cemal Gürsel'e söylediği gibi, Amerika, Lâtin Amerika ülkele- rinde yıllardır, pek çok askeri darbe görmüştü. Bu ülkelerin askeri darbele- rine Amerika adeta alışmıştı. Fakat, NATO'nun bir üyesi, 1950'den beri libe- ral demokrasiyi benimsemiş ve Batı siyasal sisteminin bir parçası haline gel- mi ş olan Türkiye'de bir "askeri darbe"nin oluşumu, Amerika'yı bir hayli şa- şırtmıştır. -

![The False Promise [Of the 'Turkish Model']](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3603/the-false-promise-of-the-turkish-model-563603.webp)

The False Promise [Of the 'Turkish Model']

THE FALSE PROMISE Ahmet T. Kuru Since the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, most Turks preserved the belief, beyond a simple expectation, that one day they would have ‘grandeur’ again. In fact, this was largely shared by some Western observers who regarded Turkey as a potential model for the coexistence of Islam and democracy. Almost a century after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, however, it would be fair to depict Turkey as a mediocre country, in terms of its military, economic, and socio-cultural capacities, and a competitive autocracy, regarding its political system. The promise of the Turkish case to combine the best parts of Islamic ethics and modern democratic institu- tions appeared to be false. What explains the failure of the idea of the ‘Turkish model?’ To simplify a complex story, one could define the competing groups in Turkish politics until 2012 as Kemalists and their discontents. For the former, it was the religious and multi-ethnic characteristics of the Ottoman Empire that led to its demise. The Turkish Republic, in contrast, had to be assertive secularist, and Turkish nationalist, to avoid repeating the maladies of the Ottoman ancien régime. This project required radical reforms, including the replacement of the Arabic alphabet with Latin, and an authoritarian regime, since the majority of Turks were conservative Muslims, and Kurds resisted assimilation. A major problem of the Kemalist understanding of Westernisation was its extreme formalism, probably due to the fact that Kemalism was primarily represented by the military. According to this formalist perspective, dress code and way of life defined the level of Westernisation of a person. -

The Origins of Greek Cypriot National Identity

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 12-1998 The Origins of Greek Cypriot National Identity Elena Koumna Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Koumna, Elena, "The Origins of Greek Cypriot National Identity" (1998). Master's Theses. 3888. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/3888 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ORIGINS OF GREEK CYPRIOT NATIONAL IDENTITY by Elena Koumna A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillmentof the requirements forthe Degree of Master of Arts Department of Political Science Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan December 1998 Copyrightby Elena Koumna 1998 To all those who never stop seeking more knowledge ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis could have never been written without the support of several people. First, I would like to thank my chair and mentor, Dr. Jim Butterfield, who patiently guided me through this challenging process. Without his initial encouragement and guidance to pursue the arguments examined here, this thesis would not have materialized. He helped me clarify and organize my thoughts at a time when my own determination to examine Greek Cypriot identity was coupled with many obstacles. His continuing support and most enlightening feedbackduring the writing of the thesis allowed me to deal with the emotional and content issues that surfaced repeatedly. -

İkinci Dünya Savaşı Sonrasında Sovyetler Birliği'nin Türkiye'den

İkinci Dünya Savaşı Sonrasında Sovyetler Birliği’nin Türkiye’den İstekleri Sabit DOKUYAN Düzce Üniversitesi DOKUYAN, Sabit, İkinci Dünya Savaşı Sonrasında Sovyetler Birliği’nin Türkiye’den İstekleri, CTAD, Yıl 9, Sayı 18 (Güz 2013), s. 119-135. İkinci Dünya Savaşı sonrasında Türkiye, Sovyetler Birliği ile yürüttüğü diplomatik ilişkiler çerçevesinde dış politikasına yön vermiştir. Türkiye’nin, Amerika Birleşik Devletleri’ne yakınlaşmasında Sovyetler Birliği’nin büyük etkisi olmuştur. Boğazlar ve sınırlar konusunda tavizler koparmaya çalışan Sovyet yönetimi, Türkiye’yi doğrudan ABD’nin yanına itmiştir. Bu yöneliş, Türkiye’nin dış politikada daha özgür ve seçici davranması önünde engel teşkil etmiştir. Cumhuriyetin kuruluşundan beri devam eden batıya yakınlaşma hız kazanmış ve tek seçenek haline gelmiştir. Türk devletinin İkinci Dünya Savaşı’na kadar devam ettirmeye çalıştığı Sovyetler Birliği ile ılımlı ilişkileri sürdürme politikası da kesintiye uğramıştır. Yeni durum, dönem iktidarları için sıkıntılı olmuş ve dış tehdit barındıran bir sürecin başladığı anlamını taşımıştır. Bu çalışmada; İkinci Dünya Savaşı’nın ardından Türkiye’yi zor durumda bırakan ve zorunlu müttefik arayışına iten Sovyet tehdidi değerlendirilmiştir. Anahtar Kelimeler: Sovyetler Birliği, Türkiye, II. Dünya Savaşı, Boğazlar, Dış Politika. DOKUYAN, Sabit, Claims of the Soviet Union on Turkish Territories after the World War II, CTAD, Year 9, Issue 18, (Fall 2013), p. 119-135. After the World War II, Turkey’s foreign policy was mainly shaped within the framework of diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union has a great effect on Turkey’s rapprochement with the United States of America from 1945 onward. It could be stressed that the Soviet threat concerning especially the Straits and eastern frontiers right after the war fueled Turkey’s journey towards west and the United States. -

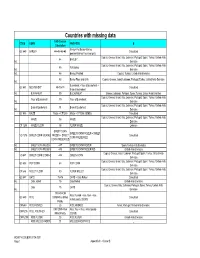

Countries with Missing Data

Countries with missing data FAO Code or CODE GEMS FAO FOOD B Calculation Barley+Pot Barley+Barley, GC 640 BARLEY 44+45+46+48 Calculated pearled+Barley Flour and grits Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Italy; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab 44 BARLEY Int. Emirates Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Italy; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab 45 Pot Barley Int. Emirates Int. 46 Barley, Pearled Cyprus; Turkey; United Arab Emirates 48 Barley Flour and Grits Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Lebanon; Portugal; Turkey; United Arab Emirates Int. Buckwheat + flour of buckwheat + GC 641 BUCKWHEAT 89+90+91 Calculated Bran of buckwheat Int. BUCKWHEAT 89 BUCKWHEAT Greece; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab Emirates Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Italy; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab Flour of Buckwheat 90 Flour of Buckwheat Int. Emirates Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Italy; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab Bran of Buckwheat 91 Bran of Buckwheat Int. Emirates GC 645 MAIZE Maize + CF1255 Maize + CF1255 (GEMS) Calculated Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Italy; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab MAIZE 56 MAIZE Emirates CF 1255 MAIZE FLOUR 58 FLOUR MAIZE Lebanon SWEET CORN SWEET CORN FROZEN + SWEET VO 1275 SWEET CORN (KERNEL FROZEN + SWEET Calculated CORN PRESERVED CORN PRESERVED Int. SWEET CORN FROZEN 447 SWEET CORN FROZEN Spain; United Arab Emirates Int. SWEET CORN PRESERV 448 SWEET CORN PRESERVED United Arab Emirates Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab VO 447 SWEET CORN (CORN-O 446 GREEN CORN Emirates Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Italy; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab GC 656 POP CORN 68 POP CORN Emirates Cyprus; Greece; Israel; Italy; Lebanon; Portugal; Spain; Turkey; United Arab CF 646 MILLET FLOUR 80 FLOUR MILLET Emirates GC 647 OATS 75+76 OATS + Oats Rolled Calculated Int. -

2017 Fall Edition

Oasis of Glenmont Cyprus Shriners Desert of New York FALL 2017 HAVING FUN. HELPING KIDS INSIDE THIS ISSUE POTENTATE’S MESSAGE 3 FALL CEREMONIAL 6 MEMBERSHIP 9 MILLION DOLLAR CLUB 13 CHIEF RABBAN’S MESSAGE 4 POTENTATE’S BALL 7 CHRISTMAS PARTY 10 UPCOMING EVENTS 14 www.cyprusshriners.com PAGE 2 CYPRUS NEWS Cyprus News Vote on proposed change to the By-Laws at Published Quarterly by Cyprus Shriners 9 Frontage Road, Glenmont, NY 12077 stated meeting Wednesday September 20, 2017 Tel: (518) 436-7892 Email: [email protected] ARTICLE V Website: www.cyprus5.org Initiation Fees, Dues, Per Capita, Hospital Levy Section 5.1 Initiation Fee The initiation fee shall 2017 Elected Divan be determined at a stated or special meeting of the Potentate Ill. Anthony T. Prizzia, Sr. (845) 691-2021 temple after notice has been given to each member [email protected] stating the proposed amount of the initiation fee. It Chief Rabban David M. Unser (518) 207-6711 must be paid in full prior to initiation. [email protected] Assistant Rabban Robert Baker (518) 857-8187 At this time the Fee for Initiation is $100.00, but [email protected] High Priest & Prophet John Donato (518) 479-0315 does not appear in the By Laws. [email protected] Oriental Guide Chris Wessell (518) 269-2262 We ask that the Initiation Fee be raised to $150.00. [email protected] Treasurer James H. Pulver (518) 326-1196 The reason for the increase is to provide every new [email protected] Noble with a Felt Embroidered Cyprus Fez at his Recorder Ill. -

Ellada Ioannou Populism and the European Elections in Cyprus

Spring 14 The Risks of growing Populism and the European elections: Populism and the European elections in Cyprus Author: Ellada Ioannou Populism and the European elections in Cyprus Ellada Ioannou1 The aim of this paper, is to examine the rise of Populism in Europe and its association with the increase in anti-European sentiments, using Cyprus as a case study. A questionnaire in the format of a survey, was completed by 1009 Cypriot participants. The findings, were that compared to other European Union member states, show that Populism and Euroscepticism in Cyprus seem, at present, not to be extensively prevalent. However, there seems to be a slight shift towards Euroscepticism and pre-conditions for the emergence and rise of radical right-wing Populism in Cyprus, are evident. Introduction While definitions of populism have varied over the years, making “populism” a rather vague and ill-defined concept, scholars and political analysts agree that its general ideology is that society is divided into two groups: the “pure people” and the “corrupt elitist” and that politics should be, above all, an expression of the general will of the people.2 With its positive connotation, it is argued, that populism can have a positive, corrective impact on democracy, by pointing out the need to integrate people’s ideas and interests into the political system and the political agenda.3 However, “populism” in general has acquired a negative connotation, as a potential threat to democracy, due to its historical association with authoritarian rule and due to some of its characteristics such as “illiberal democracy” and its exclusive nature. -

GENERAL ELECTIONS in CYPRUS 22Nd May 2016

GENERAL ELECTIONS IN CYPRUS 22nd May 2016 European Elections monitor Cyprus: first general elections after the end of the rescue plan Corinne Deloy Abstract: 542,915 Cypriots are being called to ballot on 22nd May next to appoint the 56 members of the Vouli antiprosopon (House of Representatives), the only house of parliament. 494 people from twelve different parties (5 of which have been created recently) are officially standing in this election. According to the polls undertaken by PMR&C the Sampson’s government, together with the Greek army, Democratic Rally (DISY) led by the present President managed to maintain the Turks behind a line (that then Analysis of the Republic Nicos Anastasiades is due to win the became the Green Line) before collapsing four days election with 31.5% of the vote. The Progressive later. But Turkey refused to leave the territory it was Workers’ Party is due to follow this (AKEL) with a occupying even after the fall of Nikos Sampson. On forecast of 31.5% of the vote. The Democratic Party 30th July 1974, Turkey, Greece and the UK established (DIKO) is due to win 14.3% of the vote and the a buffer zone guarded by the UN’s Blue Berets and Movement for Social Democracy (EDEK), 6% of the acknowledged the existence of two autonomous vote. administrations. On 13th February 1975 the Turkish leader Rauf Denktash proclaimed an autonomous, Around 17% of the electorate are not planning to go secular, federal State of which he was elected President to vote on 22nd May next (it is obligatory to vote in in 1976.