Science of Camel and Yak Milks: Human Nutrition and Health Perspectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Pig out to Pig

unclean meats. Cornelius was a Gentile. Gentiles were animals were not created for food. like pigs to the Israelites, they were unclean. This How can I pray over a piece of unclean meat and make it Gentile loved the Hebrew God, prayed, and gave clean….its body chemistry did not change. God did not To Pig Out money to the poor. The Father wanted Cornelius to change. He did not make it clean just because I want it. Go know His Son Jesus, and to be filled with the Holy back to Is. 65 & 66 and remember the distaste that God Or Spirit. Therefore the vision: unclean animals which the Creator of all things, has for pig. Do you want to be the Father says; “Get up, Peter. Kill and smoke in the nostrils of God? I truly pray that many of eat.” (vs.10:13) Peters reply? “No Lord?” I have you will not just discard this pamphlet as trash, but will never eaten anything impure or unclean vs. 14. This honestly seek the Father’s Word for your answers, then To Opt Out story takes place years after the death of Jesus. Peter, show Him you love Him by keeping His commandments. by this statement is saying that the Food Laws were It is obedience that shows Him how much you trust Him never changed by Jesus. Then the Father speaks a to be true to His Word. For He alone protects it and will second time, “Do not call anything impure that God cause every Word to come to pass. -

31 3 R -Ta.I¡¡V 25 Co ^ by 4^

C:9 238 Studies on Curing, Aging and_Smoking_of_Camel_Meat. II- Microbiological and Sensory Evaluation. E. T. EL-Asnwah, Salwa B. El-Magoli and M. M. Ibrahim. Dept, of Food. Sci. & Tech. Collage of Agric. Cairo University. Egypt. Introduction: Camel meat is considered as one of the toughest meat in Egypt. If camel meat could ^ plJt zed by aging, smoking and chill storage treatments while conserving other quality ritional attributes, its consumption would increase especially from elder animals. Meat structure can be considered in its simplest form to be a collection of p a rilieljher a ü ’' V^ the myofibrillar structure bound together by a connective tissue network of collQeI iCn » cot The physical properties of the myofibrillar fibers could be affected by (a) aging fit ns myofxhrillarmyofibrillar per se (.uavez(Davez andana Dickson,uicsson, i^/ui1970), , whilew u u e piuuuuxiiijproducing smallomaij. and^insig^^gonu 313fia comitant changes in the connective tissue (Bouton et al., 1973); (b) loss of molS.lit'-*1“ . ^ other changes produced by cooking (Bouton and Harris, 1972) and (c) increased^my contraction which increased muscle fiber diameter (Herring et al., 1967 b). The tissue would be affected by factors including: (a) changes in spatial orientation of collagen fibers in the connective tissue network related to myofibrillar- - - - - - contrac■ — ctr1^ _i ay. #i (Rowe, 1974) and (b) changes in the collagen produced by cooking and related to a . ifl / (Herring et al., 1967 a). Bouton et al., 1975 found that shear force values were n tegt3 _ ced by the muscle fiber properties than b'y the connective tissue properties, A}’ would be influenced by connective tissues as well as by the fiber properties. -

Bison Literature Review Biology

Bison Literature Review Ben Baldwin and Kody Menghini The purpose of this document is to compare the biology, ecology and basic behavior of cattle and bison for a management context. The literature related to bison is extensive and broad in scope covering the full continuum of domestication. The information incorporated in this review is focused on bison in more or less “wild” or free-ranging situations i.e.., not bison in close confinement or commercial production. While the scientific literature provides a solid basis for much of the basic biology and ecology, there is a wealth of information related to management implications and guidelines that is not captured. Much of the current information related to bison management, behavior (especially social organization) and practical knowledge is available through local experts, current research that has yet to be published, or popular literature. These sources, while harder to find and usually more localized in scope, provide crucial information pertaining to bison management. Biology Diet Composition Bison evolutional history provides the basis for many of the differences between bison and cattle. Bison due to their evolution in North America ecosystems are better adapted than introduced cattle, especially in grass dominated systems such as prairies. Many of these areas historically had relatively low quality forage. Bison are capable of more efficient digestion of low-quality forage then cattle (Peden et al. 1973; Plumb and Dodd 1993). Peden et al. (1973) also found that bison could consume greater quantities of low protein and poor quality forage then cattle. Bison and cattle have significant dietary overlap, but there are slight differences as well. -

Ostrich Production Systems Part I: a Review

11111111111,- 1SSN 0254-6019 Ostrich production systems Food and Agriculture Organization of 111160mmi the United Natiorp str. ro ucti s ct1rns Part A review by Dr M.M. ,,hanawany International Consultant Part II Case studies by Dr John Dingle FAO Visiting Scientist Food and , Agriculture Organization of the ' United , Nations Ot,i1 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. M-21 ISBN 92-5-104300-0 Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without any prior written permission from the copyright holders provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the copyright holders. Applications for such permission, with a statement of the purpose and extent of the reproduction, should be addressed to the Director, Information Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Viale dells Terme di Caracalla, 00100 Rome, Italy. C) FAO 1999 Contents PART I - PRODUCTION SYSTEMS INTRODUCTION Chapter 1 ORIGIN AND EVOLUTION OF THE OSTRICH 5 Classification of the ostrich in the animal kingdom 5 Geographical distribution of ratites 8 Ostrich subspecies 10 The North -

The Friday Edition September 29 2017 Home Advantage

PROPERTYINSIDE: 34-PAGESPECIAL HOME ADVANTAGE THE FRIDAY EDITION SEPTEMBER 29 2017 FE80_Cover_PRESS.indd 1 11/09/2017 16:53 THE SHARPENER alpaca punch Strong yet soft, smart yet relaxed – it’s no wonder alpaca is leading the pack this season, says Tom Stubbs fabric that’s extra light, versatile, strong yet utterly luxurious: it sounds like a menswear designer’s fantasy. But alpaca has, of course, been around for ages – it’s just that its superlative qualities have not beenA fully appreciated until this season. The springy, ultra-soft fibres from the underbellies and necks of a species of camelid living in the Andes make for some very special fabrics. When woven, alpaca takes on various textures, from soft and voluminous to coarse and cropped. And as lightweight fabrications and distinctive textures become defining characteristics of contemporary men’s style, it’s not surprising that alpaca is now being shepherded into a lead role. Brunello Cucinelli, who built his empire on cashmere, has also put alpaca to work beautifully in his signature unstructured tailored outerwear, such as a glen-check short coat (£3,760) and roomy one-and-a-half breasted camel- (£1,390) and bomber jackets (£1,060, colour coat (£3,890). Likewise at Canali, pictured below) in wool/alpaca/mohair/ where deconstructed drapey overcoats silk bouclé take inspiration from 1960s silhouettes, as does a single-breasted overcoat (£1,470) in a wool/alpaca blend. They pass muster at smart occasions, yet their subtle texture and soft construction mean they also work as weekend throw- ons. The highlight at Chester Barrie is a Change coat (£2,950, pictured below right), its navy cashmere contrasting Alpaca is ideal cable-knit turtleneck (£395) have with a lush black alpaca lapel (made by for upgrading a 1940s quality about them. -

Bison, Water Buffalo, &

February 2021 - cdfa' Bison, Water Buffalo, & Yak (or Crossbreeds) Entry Requirements ~ EPAlTMENT OF CALI FORNI \1c U LTU RE FOOD & AC Interstate Livestock Entry Permit California requires an Interstate Livestock Entry Permit for all bison, water buffalo, and/or yaks. To obtain an Interstate Livestock Entry Permit, please call the CDFA Animal Health Branch (AHB) permit line at (916) 900-5052. Permits are valid for 15 days after being issued. Certificate of Veterinary Inspection California requires a Certificate of Veterinary Inspection (CVI) for bison, water buffalo, and/or yaks within 30 days before movement into the state. Official Identification (ID) Bison, water buffalo, and/or yaks of any age and sex require official identification. Brucellosis Brucellosis vaccination is not required for bison, ------1Animal Health Branch Permit Line: water buffalo, and/or yaks to enter California. (916) 900-5052 A negative brucellosis test within 30 days prior to entry is required for all bison, water buffalo, and/ If you are transporting livestock into California or yaks 6 months of age and over with the with an electronic CVI, please print and present following exceptions: a hard copy to the Inspector at the Border • Steers or identified spayed heifers, and Protection Station. • Any Bovidae from a Certified Free Herd with the herd number and date of current Animal Health and Food Safety Services test recorded on the CVI. Animal Health Branch Headquarters - (916) 900-5002 Tuberculosis (TB) Redding District - (530) 225-2140 Modesto District - (209) 491-9350 A negative TB test is Tulare District - (559) 685-3500 required for all bison, Ontario District - (909) 947-4462 water buffalo, and/or yaks 6 months of age and over within For California entry requirements of other live- www.cdfa.ca.gov stock and animals, please visit the following: 60 days prior to Information About Livestock and Pet Movement movement. -

Carpathian Journal of Food Science and Technology El

CARPATHIAN JOURNAL OF FOOD SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY journal homepage: http://chimie-biologie.ubm.ro/carpathian_journal/index.html EL KADID A TRADITIONAL SALTED DRIED CAMEL MEAT FROM ALGERIA: CONTRIBUTION TO THE STUDY OF THE COMPOSITION IN BIOGENIC AMINE, ORGANIC ACID, AROMATIC PROFILE AND MICROBIAL BIODIVERSITY Amina Bouchefra1,2*, Tayeb Idoui1,2, Chiara Montanari3 1Laboratory of Biotechnology, Environment and Health, University Mohamed Seddik Benyahia of Jijel,Ouled Aissa City, 18000 Algeria. 2Department of Applied Microbiology and Food Sciences, University Mohamed Seddik Benyahia of Jijel,Ouled Aissa City, 18000 Algeria. 3Centro Interdipartimentale di Ricerca Industriale Agroalimentare Universitàdegli Studi di Bologna Via Quinto Bucci 336 47521 Cesena (FC), Italy. *[email protected] https://doi.org/10.34302/crpjfst/2020.12.4.9 Article history: ABSTRACT Received: Many meat preparations are manufactured in North Africa.in Algeria, the 3 January 2020 dried salted camel meat is called El kadid. The first analysis of the Accepted: composition of biogenic amine, organic acid and aromatic profile of this 1 August 2020 traditional meat was carried out in this study. El kadid is obtained by salting, Keywords: maceration and drying of camel meat. The results showed that the product El kadid; contains lactic acid (6.22 g / kg), acetic acid (<1 g / kg). Biogenic amines Biogenic amine; are present at very low concentrations (<20 mg / kg). The aromatic profile Aromatic profile; highlighted the presence of more than 60 molecules belonging to different Organic acid; chemical classes, such as aldehydes, ketones and alcohols. El Kadid presente Biodiversity. has a rich microbiological niche (Enterobacteriaceae Latic acid bateria Coagulase negative microstaphylococci yeast, Enterococci and E coli). -

A. Answer the Questions. 1. Do People Live in the Desert?

K110a Reading 1-5 Exercise A. Answer the questions. 1. Do people live in the desert? Yes, they do. No, they don’t. 2. Is a desert hot at night? Yes, it’s hot at night. No, it’s cold at night. 3. Where do people sleep in a desert?(choose 2 answers) a. In a house. b. In a cactus. c. On a camel. d. In a tent. e. Next to a kangaroo. 4. Can you ride a camel? Yes, you can ride a camel. No, you can’t ride a camel. 5. What do goats have? a. They have milk, and meat. b. They have juice, and candy. c. They have a hump. 6. What do sheep have? a. They have milk, and meat. b. They have wool, and meat, c. They have wool, and milk. 7. What is a yak? a. A yak is a small desert plant. b. A yak is a tiny desert animal. c. A yak is a big desert animal. 8. Do you want to live in a desert? Why, or why not? K110a Reading 1-5 Exercise B. Choose the correct word to complete the story. house ride tent sleep goats sheep yaks carry In a desert some people live in a ________. In a desert some people live in a _____________ in a desert. Some people move around and __________ everywhere. They have camels. They use the camels to help them. The camels _______ things. They sometimes ______ the camel! They have _________ and ________, too. In a cold desert they have ________. -

Initial Layout

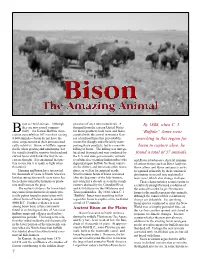

ison are wild animals. Although pearance of once numerous herds. A By 1888, when C. J. they are now raised commer- demand from the eastern United States Bcially—the Kansas Buffalo Asso- for bison products, both meat and hides, “Buffalo” Jones went ciation currently has 107 members raising coupled with the arrival in western Kan- 8,600 animals—bison do not have the sas of railroad lines that provided the searching in this region for same temperament as their domesticated means for cheaply and efficiently trans- cattle relatives. Bison, or buffalo, appear porting those products, led to a massive bison to capture alive, he docile when grazing and ruminating, but killing of bison. The killing was unregu- the mind behind the massive forehead and lated and thorough and was condoned by found a total of 37 animals. curved horns still thinks the way its an- the U.S. and state governments, anxious cestors thought. It is an animal that pre- to subdue free-roaming Indian tribes who and Bison athabascae), skeletal remains fers to run, but it is ready to fight when depended upon buffalo for food, materi- of extinct forms (such as Bison latifrons, threatened. als for shelter, and numerous other neces- Bison alleni, and Bison antiquus) can be Humans and bison have interacted sities, as well as for spiritual needs. recognized primarily by their continued for thousands of years in North America, Small remnant herds of bison remained diminution in overall size and smaller but that interaction until recent times has after the departure of the hide-hunters, horn cores, which also change in shape. -

Prospects for Rewilding with Camelids

Journal of Arid Environments 130 (2016) 54e61 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Arid Environments journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jaridenv Prospects for rewilding with camelids Meredith Root-Bernstein a, b, *, Jens-Christian Svenning a a Section for Ecoinformatics & Biodiversity, Department of Bioscience, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark b Institute for Ecology and Biodiversity, Santiago, Chile article info abstract Article history: The wild camelids wild Bactrian camel (Camelus ferus), guanaco (Lama guanicoe), and vicuna~ (Vicugna Received 12 August 2015 vicugna) as well as their domestic relatives llama (Lama glama), alpaca (Vicugna pacos), dromedary Received in revised form (Camelus dromedarius) and domestic Bactrian camel (Camelus bactrianus) may be good candidates for 20 November 2015 rewilding, either as proxy species for extinct camelids or other herbivores, or as reintroductions to their Accepted 23 March 2016 former ranges. Camels were among the first species recommended for Pleistocene rewilding. Camelids have been abundant and widely distributed since the mid-Cenozoic and were among the first species recommended for Pleistocene rewilding. They show a range of adaptations to dry and marginal habitats, keywords: Camelids and have been found in deserts, grasslands and savannas throughout paleohistory. Camelids have also Camel developed close relationships with pastoralist and farming cultures wherever they occur. We review the Guanaco evolutionary and paleoecological history of extinct and extant camelids, and then discuss their potential Llama ecological roles within rewilding projects for deserts, grasslands and savannas. The functional ecosystem Rewilding ecology of camelids has not been well researched, and we highlight functions that camelids are likely to Vicuna~ have, but which require further study. -

A Guide for Business on Textile Labelling

Argyll and Bute Council Comhairle Earra Ghàidheal agus Bhòid Development and Infrastructure Services A guide for business on textile labelling All textile products are required to carry a label indicating the fibre content, either on the item or the packaging. If a product consists of two or more components with different fibre contents, the content of each must be shown. Only certain names can be used for textile fibres and these are listed in the Regulations along with a list of products that are not required to bear fibre content. There is a now a general obligation to state the full fibre composition of textile products. In the guide What is a textile product? How should the product be labelled? Names that may be used for textile fibres Advertisements Products that do not have to bear a fibre content What is a textile product? A textile product can be defined in any of the following ways: raw, semi-worked or made up products composed of textile fibres products containing at least 80% by weight of textile products (including furniture, umbrella and sunshine coverings) textile parts of carpets, mattresses, camping goods and the warm linings of footwear, gloves, mittens (provided such parts and linings contain not less than 80% of textile fibres) textiles incorporated in, and forming an integral part of other products where textile parts are specified How should the product be labelled? All items must carry a label indicating the fibre content either on the item or the packaging. This label does not have to be permanently attached to the garment and may be removable. -

York's First Family Run Authentic

Dinner Menu NAMASTE York’s first Family run Authentic Nepalese (Gurkha Restaurant) Please inform a member of staff of any dietary or allergy requirements . 63a Goodramgate, York, YO1 7LS T: 01904 624677 • www.yakyetiyork.co.uk Email: [email protected]. Starters Aloo Dum V SS £4.99 Delicately spiced potatoes Momo with ground sesame. Momo is a type of steamed bun with a choice of filling. It has become a traditional delicacy Vegetable Pakora of Nepal, Tibet and Nepalese/ Tibetan V G £5.50 communities in Bhutan as well as all Potatoes, onions, carrots, over the Country (Recommended) ground cumin, fresh coriander and chilli to Chilli Momo taste, deep fried pakora V G S Vegetable £6.99 batter with tomato chutney. Pork £7.39 G S G S Lamb £7.39 Gurkhali Achar (New) V SS £2.50 Steamed Momo More a salad than a pickle. It’s simply Vegetable £5.90 V delicious and is best served as a starter Pork £6.10 G or side dish with rice and a meat or Lamb £6.10 G vegetable curry. Chicken Choila GF £6.99 (New) Choila is a typical dish from the Chilli Chip s V SBS £5.50 Kathmandu Valley consisting of Potato chips with stir-fry spiced grilled meat, usually eaten vegetables with fresh with beaten rice (chiura). This dish chilli to taste. is typically very spicy, mouth watering, served chilled or room temperature . Jhinge Machha G E £6.99 (Battered King Prawns) Sekuwa Pork GF £7.90 (New) Marinated with our Pork roasted on a natural wood / homemade spices & log fire in a traditional Nepalese deep fried til crispy.