The Ides of March

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C. Seth G. Bernard University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Bernard, Seth G., "Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C." (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 492. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/492 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/492 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C. Abstract MEN AT WORK: PUBLIC CONSTRUCTION, LABOR, AND SOCIETY AT MID-REPUBLICAN ROME, 390-168 B.C. Seth G. Bernard C. Brian Rose, Supervisor of Dissertation This dissertation investigates how Rome organized and paid for the considerable amount of labor that went into the physical transformation of the Middle Republican city. In particular, it considers the role played by the cost of public construction in the socioeconomic history of the period, here defined as 390 to 168 B.C. During the Middle Republic period, Rome expanded its dominion first over Italy and then over the Mediterranean. As it developed into the political and economic capital of its world, the city itself went through transformative change, recognizable in a great deal of new public infrastructure. -

De Ornanda Instruendaque Urbe Anne Truetzel

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) 1-1-2011 De Ornanda Instruendaque Urbe Anne Truetzel Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Recommended Citation Truetzel, Anne, "De Ornanda Instruendaque Urbe" (2011). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 527. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/527 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY Department of Classics De Ornanda Instruendaque Urbe: Julius Caesar’s Influence on the Topography of the Comitium-Rostra-Curia Complex by Anne E. Truetzel A thesis presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts August 2011 Saint Louis, Missouri ~ Acknowledgments~ I would like to take this opportunity to thank the Classics department at Washington University in St. Louis. The two years that I have spent in this program have been both challenging and rewarding. I thank both the faculty and my fellow graduate students for allowing me to be a part of this community. I now graduate feeling well- prepared for the further graduate study ahead of me. There are many people without whom this project in particular could not have been completed. First and foremost, I thank Professor Susan Rotroff for her guidance and support throughout this process; her insightful comments and suggestions, brilliant ideas and unfailing patience have been invaluable. -

Brief History of the Roman Empire -Establishment of Rome in 753 BC

Brief History of the Roman Empire -Establishment of Rome in 753 BC (or 625 BC) -Etruscan domination of Rome (615-509 BC) -Roman Republic (510 BC to 23 BC) -The word 'Republic' itself comes from the Latin (the language of the Romans) words 'res publica' which mean 'public matters' or 'matters of state'. Social System -Rome knew four classes of people. -The lowest class were the slaves. They were owned by other people. They had no rights at all. -The next class were the plebeians. They were free people. But they had little say at all. -The second highest class were the equestrians (sometimes they are called the 'knights'). Their name means the 'riders', as they were given a horse to ride if they were called to fight for Rome. To be an equestrian you had to be rich. -The highest class were the nobles of Rome. They were called 'patricians'. All the real power in Rome lay with them. Emperors of the Roman Empire -Imperial Period (27BC-395AD) Augustus: Rome's first emperor. He also added many territories to the empire. Nero: He was insane. He murdered his mother and his wife and threw thousands of Christians to the lions. Titus: Before he was emperor he destroyed the great Jewish temple of Solomon in Jerusalem. Trajan: He was a great conqueror. Under his rule the empire reached its greatest extent. Diocletian: He split the empire into two pieces - a western and an eastern empire. -Imperial Period (27BC-395AD) Hadrian: He built 'Hadrian's Wall' in the north of Britain to shield the province from the northern barbarians. -

The Language of Etrusco-Italic Architecture: New Perspectives on Tuscan Temples Author(S): Ingrid Edlund-Berry Source: American Journal of Archaeology, Vol

The Language of Etrusco-Italic Architecture: New Perspectives on Tuscan Temples Author(s): Ingrid Edlund-Berry Source: American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 112, No. 3 (Jul., 2008), pp. 441-447 Published by: Archaeological Institute of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20627482 Accessed: 09-06-2015 17:52 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Archaeological Institute of America is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Journal of Archaeology. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.83.205.78 on Tue, 09 Jun 2015 17:52:08 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions The Language of Etrusco-Italic Architecture: New Perspectives on Tuscan Temples INGRID EDLUND-BERRY Abstract tectura(4.7.1-5)1 and, inhis footsteps, by architectural historians and the centuries. One detail of the so-called Tuscan temple is the Etrus archaeologists through can monu I one round moulding, known from Etruria and Instead, address issue?seemingly minute?that ments in Rome. The earliest preserved example (sixth had a considerable role in determining the function century B.C.E.) comes from S. -

(Michelle-Erhardts-Imac's Conflicted Copy 2014-06-24).Pages

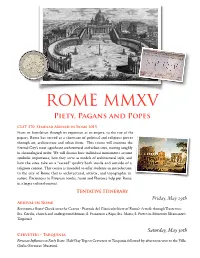

ROME MMXV Piety, Pagans and Popes CLST 370: Seminar Abroad in Rome 2015 From its foundation through its expansion as an empire, to the rise of the papacy, Rome has served as a showcase of political and religious power through art, architecture and urban form. This course will examine the Eternal City’s most significant architectural and urban sites, moving roughly in chronological order. We will discuss how individual monuments assume symbolic importance, how they serve as models of architectural style, and how the sites take on a “sacred” quality both inside and outside of a religious context. This course is intended to offer students an introduction to the city of Rome that is architectural, artistic, and topographic in nature. Excursions to Etruscan tombs, Assisi and Florence help put Rome in a larger cultural context. " Tentative Itinerary" Friday, May 29th! Arrival in Rome Benvenuto a Roma! Check into the Centro - Piazzale del Gianicolo (view of Rome) -A walk through Trastevere: Sta. Cecilia, church and underground domus; S. Francesco a Ripa; Sta. Maria; S. Pietro in Montorio (Bramante’s Tempietto)." Saturday, May 30th! Cerveteri - Tarquinia Etruscan Influences on Early Rome. Half-Day Trip to Cerveteri or Tarquinia followed by afternoon visit to the Villa " Giulia (Etruscan Museum). ! Sunday, May 31st! Circus Flaminius Foundations of Early Rome, Military Conquest and Urban Development. Isola Tiberina (cult of Asclepius/Aesculapius) - Santa Maria in Cosmedin: Ara Maxima Herculis - Forum Boarium: Temple of Hercules Victor and Temple of Portunus - San Omobono: Temples of Fortuna and Mater Matuta - San Nicola in Carcere - Triumphal Way Arcades, Temple of Apollo Sosianus, Porticus Octaviae, Theatre of Marcellus. -

Rome's Holy Mountain: the Capitoline Hill in Late Antiquity

CJ-Online, 2019.04.04 BOOK REVIEW Rome’s Holy Mountain: The Capitoline Hill in Late Antiquity. By JASON MORALEE. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2018. Pp. xxv + 278. Hardcover, $74.00. ISBN 978-0-19-049227-4. rom the marble plan of Septimius Severus (the Forma Urbis) to the De- scriptio Urbis Romae of Leon Battista Alberti, the centrality of the Capito- line hill has always been apparent. When the medieval stairway of the Ar- acoeliF was constructed, that “holy mountain” received the marble blocks from a huge temple located on the Quirinal hill; in the late 19th century it was imagined as the Mons Olympus by Giuseppe Sacconi, the architect of the Monument to King Victor Emmanuel II (in its turn compared to the sanctuary at Praeneste). Moralee’s book tackles a long, yet too often neglected, period in the Capitoline’s history – ‘from the third to the seventh centuries CE’ (or, for the sake of preci- sion, ‘from 180 to 741’) – and his investigations successfully dig into countless and poorly known literary sources, bringing to life forgotten people, monuments and stories. These are spread into seven chapters that examine different ways to experience the Capitoline, such as climbing, living and working, worshipping, remembering and destructing. In short, Moralee’s goal is to write ‘a history of the people who used the Capitoline Hill in late antiquity … and wrote about the hill’s variegated past’ (xviii). The ancient distinction between mons and collis would have deserved a brief discussion; in any case, the Capitolium was a mons and a very important one from a religious point of view – hence Moralee’s “holy mountain.” In antiquity the word Capitolium could indicate the southern summit of the hill (as opposed to the Arx) or imply the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus. -

A Bend in the River

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-01399-5 — Rome Rabun Taylor , Katherine Rinne , Spiro Kostof Excerpt More Information ONE A BEND IN THE RIVER δὶς ἐς τὸν αὐτὸν ποταμὸν οὐκ ἂν ἐμβαίης. You could not step twice into the same river. –Heraclitus hatever the genealogy of Rome’s greatness, it is not premised W on geography. The city’s physical advantages are undeniably signif- icant, but hardly peremptory; when all is said and done, the natural setting seems a poor match for such a glorious destiny. Ancient Rome had no nat- ural seaport and never dominated Mediterranean trade or transport in the manner of Carthage, Rhodes , Syracuse , or Alexandria. Nor did it command a fabulously fertile hinterland . It enjoyed no natural resources of note except clay, tolerably decent building stone, several small springs, and (we may pre- sume) some quickly depleted timberland. Its hills were defensible but its valleys marshy or l ood-prone. In its favor, Rome stood near the middle of the bus- tling Mediterranean basin at an important intersection of land routes and the Tiber , the largest and most navigable river in the region. This was an impor- tant, if hardly decisive, catalyst for the city’s rise. The city occupies the lowest viable location for a major settlement in the river basin. Along its i nal run to the sea, the Tiber’s banks are low, unstable, and prone to shifting during heavy l oods. The ruins of Ostia , the ancient port town at the river’s mouth 25 km below Rome, tell a cautionary tale: it was gradually buried in alluvium over time and its northern district was washed away by the sidewinding current. -

Musei Capitolini Piazza Del Campidoglio 1 (00186) Near Pizza Venizia Metro: Colosseo 9:30 AM - 7:30 PM (Every Day)

Musei Capitolini Piazza del Campidoglio 1 (00186) Near Pizza Venizia Metro: Colosseo 9:30 AM - 7:30 PM (Every Day) The creation of the Capitoline Museums has been traced back to 1471, when Pope Sixtus IV donated a group of bronze statues of great symbolic value to the People of Rome. The collections are closely linked to the city of Rome. Piazza del Campidoglio's current appearance dates back to the middle of the XV century when it was designed by Michelangelo Buonarroti. The piazza's component parts (buildings, sculptures and decorated paving) were intended by Michelangelo to form one single organic unity, although over the centuries there have been a number of alterations & additions. The Capitoline Hill is the smallest hill in Rome and was originally made up of two parts (the Capitolium and the Arx) separated by a deep valley which corresponds to where Piazza del Campidoglio now stands about 8 metres above the original site. The sides of this hill were very steep and on account of the difficulty of reaching the top and the dominating position it enjoyed over the River Tiber, it was chosen as the city's main stronghold. The main buildings faced the Ancient Roman Forum, from which a carriageable road known as the Clivus Capitolinus led up the hill to the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, the most important and imposing temple in Rome. In addition to this temple and those dedicated to Juno Moneta, Veiovis and in the Area Capitolina, the Capitoline Hill was the headquarters of the Public Roman Archive ( Tabularium) and, in Republican Age, of the Mint. -

Foro Romano - Roman Forum Between the Colosseum and Piazza Del Campidoglio

Foro Romano - Roman Forum Between the Colosseum and Piazza del Campidoglio. Every day: 8:30 am to one hour before sunset The Roman Forum was where religious and public life in ancient Rome took place. The Forum is, along with the Colosseum, the greatest sign of the splendour of the Roman Empire that can be seen today. After the fall of the Empire, the Roman Forum was forgotten and little by little it was buried under the earth. Although in the 16th century the existence and location of the Forum was already known, it was not until the 20th century that excavations were carried out. Interestingly, the place where the Forum was built was originally a marshy area. In the 6th century B.C. the area was drained by means of the Cloaca Maxima, one of the first sewer systems in the world. Points of interest Besides the great number of temples that are in the forum (Saturn, Venus, Romulus, Vesta, etc.), it is worth paying special attention to the following points of interest: Via Sacra: The main street in ancient Rome which linked the Piazza del Campidoglio with the Colosseum. Arch of Titus: A triumphal arch that commemorates Rome's victory over Jerusalem. It was built after the death of the emperor Titus. Arch of Septimius Severus: An arch erected in the year 203 A.D. to commemorate the third anniversary of Septimius Severus as the emperor. Temple of Antoninus and Faustina: Built in the 2nd century, the Temple of Antoninus and Faustina sets itself apart as the best preserved temple in the Roman Forum. -

The God of the Lupercal*

THE GOD OF THE LUPERCAL* By T. P. WISEMAN (Plates I-IV) On 15 February, two days after the Ides, there took place at Rome the mysterious ritual called Lupercalia, which began when the Luperci sacrificed a goat at the Lupercal. There was evidently a close conceptual and etymological connection between the name of the festival, the title of the celebrants, and the name of the sacred place: as our best-informed literary source on Roman religion, M. Terentius Varro, succinctly put it, 'the Luperci [are so called] because at the Lupercalia they sacrifice at the Lupercal . the Lupercalia are so called because [that is when] the Luperci sacrifice at the Lupercal'J What is missing in that elegantly circular definition is the name of the divinity to whom the sacrifice was made. Even the sex of the goat is unclear - Ovid and Plutarch refer to a she-goat, other sources make it male2- which might perhaps imply a similar ambiguity in the gender of the re~ipient.~Varro does indeed refer to a goddess Luperca, whom he identifies with the she-wolf of the foundation legend; he explains the name as lupapepercit, 'the she-wolf spared them' (referring to the infant twins), so I think we can take this as an elaboration on the myth, and not much help for the rit~al.~ 'Lupercalia' is one of the festival days (dies feliati) that are named in large letters on the pre-Julian calendar. (Whether that list goes back to the early regal period, as Mommsen thought, or no further than the fifth century B.c., as is argued by Agnes Kirsopp Michels in her book on the Roman ~alendar,~it is the earliest evidence we have for the Lupercalia.) There are forty-two such names, of which thirty end in -alia; and at least twenty of those thirty are formed from the name of the divinity concerned -Liberalia, Floralia, Neptunalia, Saturna- lia, and so on. -

'The Influence of Geography on the Development of Early Rome'

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. 1 ‘The Influence of Geography on the Development of early Rome’ A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Master of Arts in History; School of Humanities At Massey University, Manawatu, New Zealand Matthew Karl Putt 2018 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 3 Chapter 1: Ancient Sources ................................................................................................... 8 Chapter 2: The Geography of Rome and its Environs .......................................................... 12 Chapter 3: The Hills of Rome ............................................................................................. 20 Chapter 4: The Valleys of Rome ........................................................................................ 30 Chapter 5: The Tiber River ................................................................................................. 38 Chapter 6: The Infrastructure of Early Rome ...................................................................... 51 Conclusion .......................................................................................................................... 61 Bibliography ...................................................................................................................... -

![Atlas of Ancient Rome [PDF] Sampler](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4455/atlas-of-ancient-rome-pdf-sampler-4514455.webp)

Atlas of Ancient Rome [PDF] Sampler

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical ill. 4 Forum Nervae, aedes Minervae . Reconstruction by Meneghini, Santangeli Valenzani 2007, Inklink illustration.means without prior written permission of the publisher. Forum of Nerva Foro Nerva Imperiale © Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. ill. 22 The Forum Boarium in the late imperial period, as seen from Tiberina Island. In the foreground is the portus Tiberinus and pons Aemilius. Left to right: ianus quadrifrons, fornix Augusti, aedes Portuni, aedes Aemiliana Herculis, aedes Herculis Victoris, and the consaeptum sacellum. In the background, from left to right, are the horrea at the food of the Cernalus, insula, titulus Anastasiae on the maenianum of the domus Augusti and Circus Maximus. Reconstruction by C. Bariviera, illustration by Inklink. Forum Boarium Foro Boario © Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. Palazzo Domiziano Domitian’s Palace ill. 13 Palatium, domus Augustiana, AD 117-138. From right to left: in contact with the Augustan constructions—arcus C. Octavii, domus private Augusti, aedes Appolinis and in front of the portico—were imperial palaces; domus Tiberiana, with a substructed base used for a garden (bottom right), and domus Augustiana, facing the area Palatina (bottom left). The public buildings, surrounded by a portico on two sides, included two large receiving halls, with the so-called aula Regia in the center, sumptuous architectural decoration and a roof in imitation of a temple, and the apsed basilica to the right; these were followed by an octagonal peristyle and the so-called triclinium or cenatio Jovis.