A Bend in the River

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ides of March

P19 www.aseasonofhappiness.com The Ides of March Hey Jules, don’t be afraid... Attributed to the Bard William Shakespeare, the time of year in this spotlight was destined to become a precursor of foreboding: “Beware the Ides of March,” a soothsayer said to Julius Caesar in the play. From another source the famous historical exchange went like this: Caesar (jokingly): The Ides of March are come. Seer: Aye, Caesar, but not gone. Picture the scene: the well-to-do swanning around in togas, slaves in tow; chariots running over plebs at random in the streets; centurians rolling dice; senators whispering and plotting overthrows behind closed doors while sharpening their daggers – this was ancient Rome on the 15th March 44 B.C. Jolly Julius was sauntering on his merry way to the Theatre of Pompey, blissfully unaware that he was soon to be the star of the show as he was stabbed by no less than 60 conspirators; including his former mate Brutus to whom he commented with his dying breath: “Et tu, Brute?” And so, the Ides, for Caesar at least, turned out to be the last and worst day of his life. Maybe as well as the bucket, he also kicked off a new trend, because it wasn’t always like that. Prior to Jules messing with it, the ancient Roman calendar was complicated. Rather than numbering days of the month from the first to the last, some bright spark decided it was better to count backwards. He was probably trying to prove he was smarter than the average Roman; seeing as he understood his own calculations, whereas it was doubtful many others could. -

January 2015Watercolor Newsletter

January 2015 Watercolor Newsletter Exhibitions of Note Masters of Watercolour Exhibition Grand Hall St. Petersburg, Russia January 20-31, 2015 40 Russian and 40 International artists will be represented. Kansas Watercolor Society National Exhibition Wichita Center for the Arts Wichita, KS November 21, 2014 – January 4, 2015 NWS Annual International Exhibition NWS Gallery San Pedro, CA November 12, 2014 - January 11, 2015 Florida Focus Gold Coast Watercolor Society City Furniture Fort Lauderdale, Florida December 13, 2014- January 30, 2015 Pennsylvania Watercolor Society's 35th International Juried Exhibition State Museum Harrisburg PA November 8, 2014 – February 8, 2015 Fourth upon a time... Harriët, Eva, Kitty, Nadja Nordiska Akvarellmuseet Museum Sweden February 8 – May 3, 2015 Along with traditional and contemporary watercolour art The Nordic Watercolour Museum (Nordiska Akvarellmuseet) has a special focus on picture storytelling for children and young people. Fourth Upon a Time... Harriët, Eva, Kitty, Nadja is the fifth exhibition with this theme in focus. Here we encounter four artists and picture book creators from four European countries. They all have a deeply personal visual language and create narratives that challenge and cause one to marvel. In the exhibition, the artists will present their books, but also completely different sides of their work. They have chosen to work together and let their different worlds collide and meet in new art, new pictures and new stories. Traces: From the collection Nordiska Akvarellmuseet Museum Sweden February 8 – May 3, 2015 The Nordic Watercolour Museum´s art collection is an ongoing and vital part of the museum´s activities. For this spring´s selection works have been chosen that associate in different ways with the theme traces. -

Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C. Seth G. Bernard University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Bernard, Seth G., "Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C." (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 492. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/492 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/492 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C. Abstract MEN AT WORK: PUBLIC CONSTRUCTION, LABOR, AND SOCIETY AT MID-REPUBLICAN ROME, 390-168 B.C. Seth G. Bernard C. Brian Rose, Supervisor of Dissertation This dissertation investigates how Rome organized and paid for the considerable amount of labor that went into the physical transformation of the Middle Republican city. In particular, it considers the role played by the cost of public construction in the socioeconomic history of the period, here defined as 390 to 168 B.C. During the Middle Republic period, Rome expanded its dominion first over Italy and then over the Mediterranean. As it developed into the political and economic capital of its world, the city itself went through transformative change, recognizable in a great deal of new public infrastructure. -

Constantine Triumphal Arch 313 AD Basilica of St. Peter Ca. 324

Constantine Triumphal Arch 313 AD Basilica of St. Peter ca. 324 ff. Old St. Peter’s: reconstruction of nave, plus shrine, transept and apse. Tetrarchs from Constantinople, now in Venice Constantine defeated the rival Augustus, Maxentius, at the Pons Mulvius or Milvian Bridge north of Rome, at a place called Saxa Rubra (“Red rocks”), after seeing a vision (“In hoc signo vinces”) before the battle that he eventually associated with the protection of the Christian God. Maxentius’s Special Forces (Equites Singulares) were defeated, many drowned; the corps was abolished and their barracks given to the Bishop of Rome for the Lateran basilica. To the Emperor Flavius Constantinus Maximus Father of the Fatherland the Senate and the Roman People Because with inspiration from the divine and the might of his intelligence Together with his army he took revenge by just arms on the tyrant And his following at one and the same time, Have dedicated this arch made proud by triumphs INSTINCTV DIVINITATIS TYRANNO Reconstruction of view of colossal Sol statue (Nero, Hadrian) seen through the Arch of Constantine (from E. Marlow in Art Bulletin) Lorsch, Germany: abbey gatehouse in the form of a triumphal arch, 9th c. St. Peter’s Basilicas: vaulted vs. columns with wooden roofs Central Hall of the Markets of Trajan Basilica of Maxentius, 3018-312, completed by Constantine after 313 Basilica of Maxentius: Vaulting in concrete Basilica of Maxentius, 3018-312, completed by Constantine after 313 Monolithic Corinthian column from the Basilica of Maxentius, removed in early 1600s by Pope Paul V and brought to the piazza in front of Santa Maria Maggiore Monolithic Corinthian column from the Basilica of Maxentius, removed in early 1600s by Pope Paul V and brought to the piazza in front of Santa Maria Maggiore BATHS OF DIOCLETIAN 298-306 AD Penn Station NY (McKim, Mead, and White) St. -

De Ornanda Instruendaque Urbe Anne Truetzel

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) 1-1-2011 De Ornanda Instruendaque Urbe Anne Truetzel Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Recommended Citation Truetzel, Anne, "De Ornanda Instruendaque Urbe" (2011). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 527. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/527 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY Department of Classics De Ornanda Instruendaque Urbe: Julius Caesar’s Influence on the Topography of the Comitium-Rostra-Curia Complex by Anne E. Truetzel A thesis presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts August 2011 Saint Louis, Missouri ~ Acknowledgments~ I would like to take this opportunity to thank the Classics department at Washington University in St. Louis. The two years that I have spent in this program have been both challenging and rewarding. I thank both the faculty and my fellow graduate students for allowing me to be a part of this community. I now graduate feeling well- prepared for the further graduate study ahead of me. There are many people without whom this project in particular could not have been completed. First and foremost, I thank Professor Susan Rotroff for her guidance and support throughout this process; her insightful comments and suggestions, brilliant ideas and unfailing patience have been invaluable. -

Rome in a Pocket

FEBA ANNUAL CONVENTION 2019 TOWARDS THE NEXT DECADE. TOGHETHER ROME IN A POCKET 15-18 MAY 2019 1 When in Rome, do as Romans do The best way to visit, understand and admire the eternal city is certainly with…a pair of good shoes. Whoever crosses the old consular road of the ancient Appia, known as “Queen Viarum” notices immediately tourists in single file, walking the edge of the street on the little sidewalk. Along the way we reach the Catacombs of San Callisto and San Sebastiano, where, still today, the stones and the intricate underground tunnels, (explored for only 20 km), retain a charm of mystery and spirituality. We are in the heart of Rome, yet we find ourselves immersed in a vast archaeological park hidden by cultivated fields while, in the distance, we can see long lines of buildings. A few meters from the entrance of the Catacombs of S. Sebastiano, an almost anonymous iron gate leads to the Via Ardeatina where, a few minutes away, we find the mausoleum of the “Fosse Ardeatine”. It is the place dedicated to the 335 victims killed by the Nazi-fascist regime in March 1944, as an act of retaliation for the attack on Via Rasella by partisan groups that caused the death of German soldiers. 2 COLOSSEUM Tourists know the most symbolic In 523 A.D., the Colosseum ends place to visit and cannot fail to its active existence and begins see the Flavian amphitheater, a long period of decadence known as Colosseum due to the and abandonment to become a giant statue of Nero that stood quarry of building materials. -

Brief History of the Roman Empire -Establishment of Rome in 753 BC

Brief History of the Roman Empire -Establishment of Rome in 753 BC (or 625 BC) -Etruscan domination of Rome (615-509 BC) -Roman Republic (510 BC to 23 BC) -The word 'Republic' itself comes from the Latin (the language of the Romans) words 'res publica' which mean 'public matters' or 'matters of state'. Social System -Rome knew four classes of people. -The lowest class were the slaves. They were owned by other people. They had no rights at all. -The next class were the plebeians. They were free people. But they had little say at all. -The second highest class were the equestrians (sometimes they are called the 'knights'). Their name means the 'riders', as they were given a horse to ride if they were called to fight for Rome. To be an equestrian you had to be rich. -The highest class were the nobles of Rome. They were called 'patricians'. All the real power in Rome lay with them. Emperors of the Roman Empire -Imperial Period (27BC-395AD) Augustus: Rome's first emperor. He also added many territories to the empire. Nero: He was insane. He murdered his mother and his wife and threw thousands of Christians to the lions. Titus: Before he was emperor he destroyed the great Jewish temple of Solomon in Jerusalem. Trajan: He was a great conqueror. Under his rule the empire reached its greatest extent. Diocletian: He split the empire into two pieces - a western and an eastern empire. -Imperial Period (27BC-395AD) Hadrian: He built 'Hadrian's Wall' in the north of Britain to shield the province from the northern barbarians. -

The Argei: Sex, War, and Crucifixion in Rome

THE ARGEI: SEX, WAR, AND CRUCIFIXION IN ROME AND THE ANCIENT NEAR EAST Kristan Foust Ewin, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2012 APPROVED: Christopher J. Fuhrmann, Major Professor Ken Johnson, Committee Member Walt Roberts, Committee Member Richard B. McCaslin, Chair of the Department of History James D. Meernik, Acting Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Ewin, Kristan Foust. The Argei: Sex, War, and Crucifixion in Rome and the Ancient Near East. Master of Arts (History), May 2012, 119 pp., 2 tables, 18 illustrations, bibliography, 150 titles. The purpose of the Roman Argei ceremony, during which the Vestal Virgins harvested made and paraded rush puppets only to throw them into the Tiber, is widely debated. Modern historians supply three main reasons for the purpose of the Argei: an agrarian act, a scapegoat, and finally as an offering averting deceased spirits or Lares. I suggest that the ceremony also related to war and the spectacle of displaying war casualties. I compare the ancient Near East and Rome and connect the element of war and husbandry and claim that the Argei paralleled the sacred marriage. In addition to an agricultural and purification rite, these rituals may have served as sympathetic magic for pre- and inter-war periods. As of yet, no author has proposed the Argei as a ceremony related to war. By looking at the Argei holistically I open the door for a new direction of inquiry on the Argei ceremony, fertility cults in the Near East and in Rome, and on the execution of war criminals. -

The Language of Etrusco-Italic Architecture: New Perspectives on Tuscan Temples Author(S): Ingrid Edlund-Berry Source: American Journal of Archaeology, Vol

The Language of Etrusco-Italic Architecture: New Perspectives on Tuscan Temples Author(s): Ingrid Edlund-Berry Source: American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 112, No. 3 (Jul., 2008), pp. 441-447 Published by: Archaeological Institute of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20627482 Accessed: 09-06-2015 17:52 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Archaeological Institute of America is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Journal of Archaeology. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.83.205.78 on Tue, 09 Jun 2015 17:52:08 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions The Language of Etrusco-Italic Architecture: New Perspectives on Tuscan Temples INGRID EDLUND-BERRY Abstract tectura(4.7.1-5)1 and, inhis footsteps, by architectural historians and the centuries. One detail of the so-called Tuscan temple is the Etrus archaeologists through can monu I one round moulding, known from Etruria and Instead, address issue?seemingly minute?that ments in Rome. The earliest preserved example (sixth had a considerable role in determining the function century B.C.E.) comes from S. -

Unfolding Rome: Giovanni Battista Piranesi╎s Le Antichit〠Romane

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2008 Unfolding Rome: Giovanni Battista Piranesi's Le Antichità Romane, Volume I (1756) Sarah E. Buck Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF VISUAL ARTS, THEATRE, AND DANCE UNFOLDING ROME: GIOVANNI BATTISTA PIRANESI’S LE ANTICHITÀ ROMANE, VOLUME I (1756) By Sarah E. Buck A Thesis submitted to the Department of Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2008 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of Sarah Elizabeth Buck defended on April 30th, 2008. ____________________________________ Robert Neuman Professor Directing Thesis ____________________________________ Lauren Weingarden Committee Member ____________________________________ Stephanie Leitch Committee Member Approved: ____________________________________________ Richard Emmerson, Chair, Department of Art History ____________________________________________ Sally E. McRorie, Dean, College of Visual Arts, Theatre and Dance The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis grew out of a semester paper from Robert Neuman’s Eighteenth-Century Art class, one of my first classes in the FSU Department of Art History. Developing the paper into a larger project has been an extremely rewarding experience, and I wish to thank Dr. Neuman for his continual guidance, advice, and encouragement from the very beginning. I am additionally deeply grateful for and appreciative of the valuable input and patience of my thesis committee members, Lauren Weingarden and Stephanie Leitch. Thanks also go to the staff of the University of Florida-Gainesville’s Rare Book Collection, to Jack Freiberg, Rick Emmerson, Jean Hudson, Kathy Braun, and everyone else who has been part of my graduate school community in the Department of Art History. -

(Michelle-Erhardts-Imac's Conflicted Copy 2014-06-24).Pages

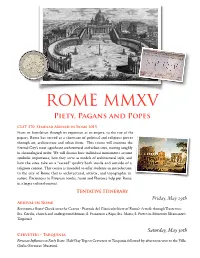

ROME MMXV Piety, Pagans and Popes CLST 370: Seminar Abroad in Rome 2015 From its foundation through its expansion as an empire, to the rise of the papacy, Rome has served as a showcase of political and religious power through art, architecture and urban form. This course will examine the Eternal City’s most significant architectural and urban sites, moving roughly in chronological order. We will discuss how individual monuments assume symbolic importance, how they serve as models of architectural style, and how the sites take on a “sacred” quality both inside and outside of a religious context. This course is intended to offer students an introduction to the city of Rome that is architectural, artistic, and topographic in nature. Excursions to Etruscan tombs, Assisi and Florence help put Rome in a larger cultural context. " Tentative Itinerary" Friday, May 29th! Arrival in Rome Benvenuto a Roma! Check into the Centro - Piazzale del Gianicolo (view of Rome) -A walk through Trastevere: Sta. Cecilia, church and underground domus; S. Francesco a Ripa; Sta. Maria; S. Pietro in Montorio (Bramante’s Tempietto)." Saturday, May 30th! Cerveteri - Tarquinia Etruscan Influences on Early Rome. Half-Day Trip to Cerveteri or Tarquinia followed by afternoon visit to the Villa " Giulia (Etruscan Museum). ! Sunday, May 31st! Circus Flaminius Foundations of Early Rome, Military Conquest and Urban Development. Isola Tiberina (cult of Asclepius/Aesculapius) - Santa Maria in Cosmedin: Ara Maxima Herculis - Forum Boarium: Temple of Hercules Victor and Temple of Portunus - San Omobono: Temples of Fortuna and Mater Matuta - San Nicola in Carcere - Triumphal Way Arcades, Temple of Apollo Sosianus, Porticus Octaviae, Theatre of Marcellus. -

The Colosseum As an Enduring Icon of Rome: a Comparison of the Reception of the Colosseum and the Circus Maximus

The Colosseum as an Enduring Icon of Rome: A Comparison of the Reception of the Colosseum and the Circus Maximus. “While stands the Coliseum, Rome shall stand; When falls the Coliseum, Rome shall fall; And when Rome falls - the World.”1 The preceding quote by Lord Byron is just one example of how the Colosseum and its spectacles have captivated people for centuries. However, before the Colosseum was constructed, the Circus Maximus served as Rome’s premier entertainment venue. The Circus was home to gladiator matches, animal hunts, and more in addition to the chariot races. When the Colosseum was completed in 80 CE, it became the new center of ancient Roman amusement. In the modern day, thousands of tourists each year visit the ruins of the Colosseum, while the Circus Maximus serves as an open field for joggers, bikers, and other recreational purposes, and is not necessarily an essential stop for tourists. The ancient Circus does not draw nearly the same crowds that the Colosseum does. Through an analysis of the sources, there are several explanations as to why the Colosseum remains a popular icon of Rome while the Circus Maximus has been neglected by many people, despite it being older than and just as popular as the Colosseum in ancient times. Historiography Early scholarship on the Colosseum and other amphitheaters focused on them as sites of death and immorality. Katherine Welch sites L. Friedländer as one who adopted such a view, 1 George Gordon Byron, “Childe Harold's Pilgrimage, canto IV, st. 145,” in The Selected Poetry of Lord Byron, edited by Leslie A.