LES SILENCES DU PALAIS and INCENDIES Anna Bernard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alternative Digital Movies As Malaysian National Cinema A

Unfolding Time to Configure a Collective Entity: Alternative Digital Movies as Malaysian National Cinema A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Hsin-ning Chang April 2017 © 2017 Hsin-ning Chang. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Unfolding Time to Configure a Collective Entity: Alternative Digital Movies as Malaysian National Cinema by HSIN-NING CHANG has been approved for Interdisciplinary Arts and the College of Fine Arts by Erin Schlumpf Visiting Assistant Professor of Film Studies Elizabeth Sayrs Interim Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 ABSTRACT CHANG, HSIN-NING, Ph.D., April 2017, Interdisciplinary Arts Unfolding Time to Configure a Collective Entity: Alternative Digital Movies as Malaysian National Cinema Director of dissertation: Erin Schlumpf This dissertation argues that the alternative digital movies that emerged in the early 21st century Malaysia have become a part of the Malaysian national cinema. This group of movies includes independent feature-length films, documentaries, short and experimental films and videos. They closely engage with the unique conditions of Malaysia’s economic development, ethnic relationships, and cultural practices, which together comprise significant understandings of the nationhood of Malaysia. The analyses and discussions of the content and practices of these films allow us not only to recognize the economic, social, and historical circumstances of Malaysia, but we also find how these movies reread and rework the existed imagination of the nation, and then actively contribute in configuring the collective entity of Malaysia. 4 DEDICATION To parents, family, friends, and cats in my life 5 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my advisor, Prof. -

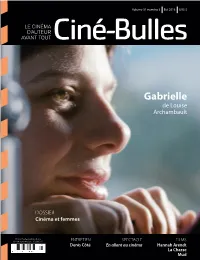

Gabrielle De Louise Archambault

Volume 31 numéro 3 Été 2013 5,95 $ ÉTÉ 2013 Gabrielle de Louise Archambault DOSSIER Cinéma et femmes REVUE DE CINÉMA PUBLIÉE PAR L’ASSOCIATION DES CINÉMAS PARALLÈLES DU QUÉBEC VOLUME 31 NUMÉRO 3 VOLUME DU QUÉBEC PARALLÈLES DES CINÉMAS L’ASSOCIATION PUBLIÉE PAR REVUE DE CINÉMA Envoi Poste-publications No de convention : 40069242 ENTRETIEN SPECTACLE FILMS Denis Côté En allant au cinéma Hannah Arendt La Chasse Mud C0 M49 Y66 K0 Volume 31 numéro 3 Été 2013 2 EN COUVERTURE Gabrielle 2 Entretien avec Louise Archambault SOMMAIRE 8 Commentaire critique ENTRETIEN 12 Denis Côté Scénariste et réalisateur de Vic et Flo ont vu un ours 20 Commentaire critique SPECTACLE 12 59 56 En allant au cinéma FILMS 10 Hannah Arendt de Margarethe von Trotta 58 Au-delà des collines de Cristian Mungiu 59 La Chasse de Thomas Vinterberg 60 The Great Gatsby de Baz Luhrmann 61 Mud de Je Nichols 62 Sarah préfère la course de Chloé Robichaud 10 63 This Must Be the Place de Paolo Sorrentino 23 Introduction au dossier 24 Les pionnières québécoises 28 Au Québec en 2013 38 L’horreur au féminin 42 Le combat émancipateur 46 Du masculin au féminin 50 Les lms les plus populaires 54 Coret 20 Courts et grand talent Volume 31 numéro 3 Été 2013 RÉDACTION ÉDITION ABONNEMENT ANNUEL PAYABLE À L’ACPQ (4 NUMÉROS) Éric Perron, rédacteur en chef Association des cinémas parallèles du Québec (ACPQ) Individuel : 23 $ – Institutionnel : 45,99 $ (taxes comprises) [email protected] Martine Mauroy, directrice générale Étranger : 60 $ (non taxable) 514.252.3021 poste 3413 4545, av. -

Download-To-Own and Online Rental) and Then to Subscription Television And, Finally, a Screening on Broadcast Television

Exporting Canadian Feature Films in Global Markets TRENDS, OPPORTUNITIES AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS MARIA DE ROSA | MARILYN BURGESS COMMUNICATIONS MDR (A DIVISION OF NORIBCO INC.) APRIL 2017 PRODUCED WITH THE ASSISTANCE OF 1 EXPORTING CANADIAN FEATURE FILMS IN GLOBAL MARKETS Acknowledgements This study was commissioned by the Canadian Media Producers Association (CMPA), in partnership with the Association québécoise de la production médiatique (AQPM), the Cana- da Media Fund (CMF), and Telefilm Canada. The following report solely reflects the views of the authors. Findings, conclusions or recom- mendations expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funders of this report, who are in no way bound by any recommendations con- tained herein. 2 EXPORTING CANADIAN FEATURE FILMS IN GLOBAL MARKETS Executive Summary Goals of the Study The goals of this study were three-fold: 1. To identify key trends in international sales of feature films generally and Canadian independent feature films specifically; 2. To provide intelligence on challenges and opportunities to increase foreign sales; 3. To identify policies, programs and initiatives to support foreign sales in other jurisdic- tions and make recommendations to ensure that Canadian initiatives are competitive. For the purpose of this study, Canadian film exports were defined as sales of rights. These included pre-sales, sold in advance of the completion of films and often used to finance pro- duction, and sales of rights to completed feature films. In other jurisdictions foreign sales are being measured in a number of ways, including the number of box office admissions, box of- fice revenues, and sales of rights. -

ZOOM- Press Kit.Docx

PRESENTS ZOOM PRODUCTION NOTES A film by Pedro Morelli Starring Gael García Bernal, Alison Pill, Mariana Ximenes, Don McKellar Tyler Labine, Jennifer Irwin and Jason Priestley Theatrical Release Date: September 2, 2016 Run Time: 96 Minutes Rating: Not Rated Official Website: www.zoomthefilm.com Facebook: www.facebook.com/screenmediafilm Twitter: @screenmediafilm Instagram: @screenmediafilms Theater List: http://screenmediafilms.net/productions/details/1782/Zoom Trailer: www.youtube.com/watch?v=M80fAF0IU3o Publicity Contact: Prodigy PR, 310-857-2020 Alex Klenert, [email protected] Rob Fleming, [email protected] Screen Media Films, Elevation Pictures, Paris Filmes,and WTFilms present a Rhombus Media and O2 Filmes production, directed by Pedro Morelli and starring Gael García Bernal, Alison Pill, Mariana Ximenes, Don McKellar, Tyler Labine, Jennifer Irwin and Jason Priestley in the feature film ZOOM. ZOOM is a fast-paced, pop-art inspired, multi-plot contemporary comedy. The film consists of three seemingly separate but ultimately interlinked storylines about a comic book artist, a novelist, and a film director. Each character lives in a separate world but authors a story about the life of another. The comic book artist, Emma, works by day at an artificial love doll factory, and is hoping to undergo a secret cosmetic procedure. Emma’s comic tells the story of Edward, a cocky film director with a debilitating secret about his anatomy. The director, Edward, creates a film that features Michelle, an aspiring novelist who escapes to Brazil and abandons her former life as a model. Michelle, pens a novel that tells the tale of Emma, who works at an artificial love doll factory… And so it goes.. -

Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research

University of Alberta The Performance of Identity in Wajdi Mouawad’s Incendies by Nicole Renault A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Drama ©Nicole Renault Fall 2009 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-54187-6 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-54187-6 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. -

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List Denotes new titles recently added to the list while the severity of her older sister's injuries Abuse and the urging of her younger sister, their uncle, and a friend tempt her to testify against Anderson, Laurie Halse him, her mother and other well-meaning Speak adults persuade her to claim responsibility. A traumatic event in the (Mature) (2007) summer has a devastating effect on Melinda's freshman Flinn, Alexandra year of high school. (2002) Breathing Underwater Sent to counseling for hitting his Avasthi, Swati girlfriend, Caitlin, and ordered to Split keep a journal, A teenaged boy thrown out of his 16-year-old Nick examines his controlling house by his abusive father goes behavior and anger and describes living with to live with his older brother, his abusive father. (2001) who ran away from home years earlier under similar circumstances. (Summary McCormick, Patricia from Follett Destiny, November 2010). Sold Thirteen-year-old Lakshmi Draper, Sharon leaves her poor mountain Forged by Fire home in Nepal thinking that Teenaged Gerald, who has she is to work in the city as a spent years protecting his maid only to find that she has fragile half-sister from their been sold into the sex slave trade in India and abusive father, faces the that there is no hope of escape. (2006) prospect of one final confrontation before the problem can be solved. McMurchy-Barber, Gina Free as a Bird Erskine, Kathryn Eight-year-old Ruby Jean Sharp, Quaking born with Down syndrome, is In a Pennsylvania town where anti- placed in Woodlands School in war sentiments are treated with New Westminster, British contempt and violence, Matt, a Columbia, after the death of her grandmother fourteen-year-old girl living with a Quaker who took care of her, and she learns to family, deals with the demons of her past as survive every kind of abuse before she is she battles bullies of the present, eventually placed in a program designed to help her live learning to trust in others as well as her. -

1997 Sundance Film Festival Awards Jurors

1997 SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL The 1997 Sundance Film Festival continued to attract crowds, international attention and an appreciative group of alumni fi lmmakers. Many of the Premiere fi lmmakers were returning directors (Errol Morris, Tom DiCillo, Victor Nunez, Gregg Araki, Kevin Smith), whose earlier, sometimes unknown, work had received a warm reception at Sundance. The Piper-Heidsieck tribute to independent vision went to actor/director Tim Robbins, and a major retrospective of the works of German New-Wave giant Rainer Werner Fassbinder was staged, with many of his original actors fl own in for forums. It was a fi tting tribute to both Fassbinder and the Festival and the ways that American independent cinema was indeed becoming international. AWARDS GRAND JURY PRIZE JURY PRIZE IN LATIN AMERICAN CINEMA Documentary—GIRLS LIKE US, directed by Jane C. Wagner and LANDSCAPES OF MEMORY (O SERTÃO DAS MEMÓRIAS), directed by José Araújo Tina DiFeliciantonio SPECIAL JURY AWARD IN LATIN AMERICAN CINEMA Dramatic—SUNDAY, directed by Jonathan Nossiter DEEP CRIMSON, directed by Arturo Ripstein AUDIENCE AWARD JURY PRIZE IN SHORT FILMMAKING Documentary—Paul Monette: THE BRINK OF SUMMER’S END, directed by MAN ABOUT TOWN, directed by Kris Isacsson Monte Bramer Dramatic—HURRICANE, directed by Morgan J. Freeman; and LOVE JONES, HONORABLE MENTIONS IN SHORT FILMMAKING directed by Theodore Witcher (shared) BIRDHOUSE, directed by Richard C. Zimmerman; and SYPHON-GUN, directed by KC Amos FILMMAKERS TROPHY Documentary—LICENSED TO KILL, directed by Arthur Dong Dramatic—IN THE COMPANY OF MEN, directed by Neil LaBute DIRECTING AWARD Documentary—ARTHUR DONG, director of Licensed To Kill Dramatic—MORGAN J. -

YANA MEERZON This Essay Examines the Forms of History and Memory Representation in Incendies, the 2004 Play by Wajdi Mouawad, An

YANA MEERZON STAGING MEMORY IN WAJDI MOUAWAD ’S INCENDIES : ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE OR POETIC VENUE ? This essay examines the forms of history and memory representation in Incendies , the 2004 play by Wajdi Mouawad, and its 2010 film version, directed by Denis Villeneuve. Incendies tells the story of a twin brother and sister on the quest to uncover the mystery of their mother’s past and the silence of her last years. A contemporary re-telling of the Oedipus myth, the play examines what kind of cultural, collective, and individual memo - ries inform the journeys of its characters, who are exilic children. The play serves Mouawad as a public platform to stage the testimony of his child - hood trauma: the trauma of war, the trauma of exilic adaptation, and the challenges of return. As this essay argues, when moved from one medium to another, Mouawad’s work forces the directors to seek its historical and geographical contextualization. If in its original staging, Incendies allows Mouawad to elevate the story of his personal suffering to the universals of abandoned childhood, to reach in its language the realms of poetic expres - sion, and to make memory a separate, almost tangible entity on stage, then the 2010 film version by Villeneuve turns this play into an archaeological site to excavate the recent history of a single war-torn Middle East country (supposedly Lebanon), an objective at odds with Mouawad’s own view of theatre as a venue where poetry meets politics. Naturally the transposition from a play to a film presupposes a significant mutation of the original and raises questions of textual fidelity. -

Theatre Film Incendies Comparaison

De la pièce de théâtre au film L'auteur(de(la(pièce(de(théâtre(:(Wajdi(MOUAWAD((1968)! - Wajdi MOUAWAD est né au Liban en 1968. - Il quitte ce pays à l'âge de 8 ans, durant la guerre civile. - Il part avec sa famille vivre en France, puis au Québec. - Diplômé (en 1991) en interprétation de l'École nationale de théâtre du Canada à Montréal, il est comédien, auteur et metteur en scène. - En 2009, il est l’artiste associé de la 63ème édition du Festival d’Avignon. - Toujours en 2009 [? À vérifier !], il reçoit le grand prix du théâtre de l’Académie française pour l’ensemble de son œuvre dramatique. La(pièce(de(théâtre( Création de la pièce Date et lieu de création : le 14 mars 2003 au Théâtre de Quat'Sous à Montréal - Incendies est créé le 14 mars 2003 au Théâtre de Quat'Sous à Montréal. Incendies est le deuxième volet de la tétralogie « Le sang des promesses » - La tétralogie « Le sang des promesses » comprend également : * Littoral (1997 ; nouvelle version : 2009) * Forêts (2006) * Ciels (2009). Inspiration - Pièce écrite en réaction à la guerre en Irak. Caractéristiques de la pièce La pièce la plus réaliste de la tétralogie « Le sang des promesses » - C'est selon Wajdi MOUAWAD lui-même la pièce la plus réaliste de la tétralogie « Le sang des promesses ». Problématiques de la pièce - Tout comme Littoral, cette pièce travaille autour de la question de l'origine. Une pièce créée avec et grâce aux comédiens qui l'interprètent - Selon Wajdi MOUAWAD, cette pièce « n'aurait jamais vu le jour sans la participation des comédiens. -

We Are French. Et Anglais Nous Restons

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses Dissertations and Theses August 2014 We Are French. Et Anglais Nous Restons. Alison Jane Bowie University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2 Part of the Cultural History Commons, Dramatic Literature, Criticism and Theory Commons, Fine Arts Commons, French and Francophone Literature Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, Other Theatre and Performance Studies Commons, Performance Studies Commons, Playwriting Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, and the Theatre History Commons Recommended Citation Bowie, Alison Jane, "We Are French. Et Anglais Nous Restons." (2014). Masters Theses. 4. https://doi.org/10.7275/5415302 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2/4 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ! ! We Are French. Et Anglais Nous Restons. Rethinking translation and adaptation for the stage as a tool for affecting bicultural and bilingual identity through an analysis and the practice of translating and adapting Armand Leclaire's 1916 ! play Le petit maître d'école ! ! ! ! A Thesis Presented By ALISON JANE BOWIE ! ! ! Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of -

Diplomarbeit Pia Bodenseher

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Joseph Quesnel et Michel Tremblay – Le théâtre révolutionnaire au Québec : De ses origines à la modernité“ Verfasserin Pia Bodenseher angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien, 2011 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 236 346 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Diplomstudium Romanistik Französisch Betreuer: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Jörg Türschmann Table des matières INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................................3 1. L’HISTOIRE DU THÉÂTRE AU QUÉBEC – DU «THÉÂTRE DE NEPTUNE» AUX « BELLES-SŒURS »..................................................................6 1.1. 1606 – 1758................................................................................................6 1.1.1. Le théâtre de Neptune..................................................................6 1.1.2. L’influence du clergé sur l’activité théâtrale ..............................7 1.2. 1765 – 1898..............................................................................................12 1.2.1. Les troupes anglophones et le théâtre de garnison...................12 1.2.2. Le théâtre de société..................................................................13 1.3. 1890 – 1929..............................................................................................15 1.3.1. La pratique scénique des minorités culturelles .........................17 1.3.2. L’âge d’or du théâtre et la concurrence cinématographique ...18 1.4. 1930 – 1968..............................................................................................19 -

The Complete Stories

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka a.b.e-book v3.0 / Notes at the end Back Cover : "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. Page 1 The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.