Poetic and Social Development in Indian English Poetry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Annual Report 2014 - 2015 Ministry of Culture Government of India

ANNUAL REPORT 2014 - 2015 MINISTRY OF CULTURE GOVERNMENT OF INDIA Annual Report 2014-15 1 Ministry of Culture 2 Detail from Rani ki Vav, Patan, Gujarat, A World Heritage Site Annual Report 2014-15 CONTENTS 1. Ministry of Culture - An Overview – 5 2. Tangible Cultural Heritage 2.1 Archaeological Survey of India – 11 2.2 Museums – 28 2.2a National Museum – 28 2.2b National Gallery of Modern Art – 31 2.2c Indian Museum – 37 2.2d Victoria Memorial Hall – 39 2.2e Salar Jung Museum – 41 2.2f Allahabad Museum – 44 2.2g National Council of Science Museum – 46 2.3 Capacity Building in Museum related activities – 50 2.3a National Museum Institute of History of Art, Conservation and Museology – 50 2.3.b National Research Laboratory for conservation of Cultural Property – 51 2.4 National Culture Fund (NCF) – 54 2.5 International Cultural Relations (ICR) – 57 2.6 UNESCO Matters – 59 2.7 National Missions – 61 2.7a National Mission on Monuments and Antiquities – 61 2.7b National Mission for Manuscripts – 61 2.7c National Mission on Libraries – 64 2.7d National Mission on Gandhi Heritage Sites – 65 3. Intangible Cultural Heritage 3.1 National School of Drama – 69 3.2 Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts – 72 3.3 Akademies – 75 3.3a Sahitya Akademi – 75 3.3b Lalit Kala Akademi – 77 3.3c Sangeet Natak Akademi – 81 3.4 Centre for Cultural Resources and Training – 85 3.5 Kalakshetra Foundation – 90 3.6 Zonal cultural Centres – 94 3.6a North Zone Cultural Centre – 95 3.6b Eastern Zonal Cultural Centre – 95 3.6c South Zone Cultural Centre – 96 3.6d West Zone Cultural Centre – 97 3.6e South Central Zone Cultural Centre – 98 3.6f North Central Zone Cultural Centre – 98 3.6g North East Zone Cultural Centre – 99 Detail from Rani ki Vav, Patan, Gujarat, A World Heritage Site 3 Ministry of Culture 4. -

403 Little Magazines in India and Emergence of Dalit

Volume: II, Issue: III ISSN: 2581-5628 An International Peer-Reviewed Open GAP INTERDISCIPLINARITIES - Access Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies LITTLE MAGAZINES IN INDIA AND EMERGENCE OF DALIT LITERATURE Dr. Preeti Oza St. Andrew‘s College Mumbai University [email protected] INTRODUCTION As encyclopaedia Britannica defines: ―Little Magazine is any of various small, usually avant-garde periodicals devoted to serious literary writings.‖ The name signifies most of all a usually non-commercial manner of editing, managing, and financing. They were published from 1880 through much of the 20th century and flourished in the U.S. and England, though French and German writers also benefited from them. HISTORY Literary magazines or ‗small magazines‘ are traced back in the UK since the 1800s. Americas had North American Review (founded in 1803) and the Yale Review(1819). In the 20th century: Poetry Magazine, published in Chicago from 1912, has grown to be one of the world‘s most well-regarded journals. The number of small magazines rapidly increased when the th independent Printing Press originated in the mid 20 century. Small magazines also encouraged substantial literary influence. It provided a very good space for the marginalised, the new and the uncommon. And that finally became the agenda of all small magazines, no matter where in the world they are published: To promote literature — in a broad, all- encompassing sense of the word — through poetry, short fiction, essays, book reviews, literary criticism and biographical profiles and interviews of authors. Little magazines heralded a change in literary sensibility and in the politics of literary taste. They also promoted alternative perspectives to politics, culture, and society. -

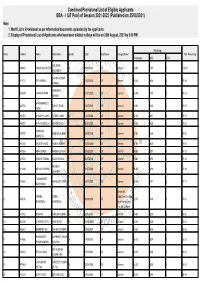

Of Session 2021-2022 (Published on 25/08/2021) Note: 1

Combined Provisional List of Eligible Applicants BBA - I (UT Pool) of Session 2021-2022 (Published on 25/08/2021) Note: 1. Merit List is Provisional as per information/documents uploaded by the applicants. 2. Display of Provisional List of Applicants who have been allotted college will be on 28th August, 2021 by 5.00 PM Weightage Sr No FormNo Name FatherName Gender DOB PoolName CategoryName Total Percentage Percentage NSS NCC GULSHAN 1 A56963 PARAS SACHDEVA M 14/09/2002 UT General 98.40 1.97 0 100.37 SACHDEVA SANJAY KUMAR 2 A17017 RIIT KAMBOJ F 12/02/2003 UT General 98.20 0.98 0 99.18 KAMBOJ VIRENDER 3 A22529 AVANI DHIMAN F 01/07/2003 UT General 96.40 1.93 0 98.33 DHIMAN HARMANPREET 4 A42740 SURJIT SINGH F 03/07/2003 UT General 98.20 0.00 0 98.20 KAUR 5 A22973 SHAURYA LAKHI RITESH LAKHI M 11/07/2003 UT General 97.00 0.97 0 97.97 6 A40877 BHAVYA SINGLA ASHOK SINGLA F 30/01/2003 UT General 97.60 0.00 0 97.60 VANSHIKA 7 A37157 NARESH KUMAR F 22/08/2003 UT General 97.60 0.00 0 97.60 PAPNEJA 8 A24348 GAURJA GARG VISHNU KUMAR F 05/10/2003 UT General 97.60 0.00 0 97.60 9 A23365 ABHA SINGH JANGRAJ SINGH F 04/08/2003 UT General 96.60 0.97 0 97.57 10 A14723 CHAHAT SINGLA RAJAN SINGLA F 20/07/2003 UT General 96.40 0.96 0 97.36 MUKESH 11 A11930 MEHAK SHARMA F 31/07/2003 UT General 96.40 0.96 0 97.36 CHANDER TARANPREET 12 A15824 AMARJEET SINGH F 24/11/2003 UT General 95.40 1.91 0 97.31 KAUR SAINI Single Girl VRINDA VISHAL Child/One Girl Child 13 A58018 F 06/03/2003 UT 97.00 0.00 0 97.00 BHARDWAJ BHARDWAJ out of the only the Two Girl Children 14 A12762 RAGHAV NARESH KUMAR M 20/03/2003 UT General 96.80 0.00 0 96.80 15 A24046 UTKARSH SETHI RAVI SETHI M 07/02/2004 UT Defence 96.60 0.00 0 96.60 16 A26661 SAMRIDHI VIG SANJEEV KUMAR F 09/02/2004 UT General 95.60 0.96 0 96.56 HARSHDEEP GURPREET SINGH 17 A19686 M 19/09/2002 UT General 96.20 0.00 0 96.20 SINGH SANDHU SANDHU MR. -

Madhusudan Dutt and the Dilemma of the Early Bengali Theatre Dhrupadi

Layered homogeneities: Madhusudan Dutt and the dilemma of the early Bengali theatre Dhrupadi Chattopadhyay Vol. 4, No. 2, pp. 5–34 | ISSN 2050-487X | www.southasianist.ed.ac.uk 2016 | The South Asianist 4 (2): 5-34 | pg. 5 Vol. 4, No. 2, pp. 5-34 Layered homogeneities: Madhusudan Dutt, and the dilemma of the early Bengali theatre DHRUPADI CHATTOPADHYAY, SNDT University, Mumbai Owing to its colonial tag, Christianity shares an uneasy relationship with literary historiographies of nineteenth-century Bengal: Christianity continues to be treated as a foreign import capable of destabilising the societal matrix. The upper-caste Christian neophytes, often products of the new western education system, took to Christianity to register socio-political dissent. However, given his/her socio-political location, the Christian convert faced a crisis of entitlement: as a convert they faced immediate ostracising from Hindu conservative society, and even as devout western moderns could not partake in the colonizer’s version of selective Christian brotherhood. I argue that Christian convert literature imaginatively uses Hindu mythology as a master-narrative to partake in both these constituencies. This paper turns to the reception aesthetics of an oft forgotten play by Michael Madhusudan Dutt, the father of modern Bengali poetry, to explore the contentious relationship between Christianity and colonial modernity in nineteenth-century Bengal. In particular, Dutt’s deft use of the semantic excess as a result of the overlapping linguistic constituencies of English and Bengali is examined. Further, the paper argues that Dutt consciously situates his text at the crossroads of different receptive constituencies to create what I call ‘layered homogeneities’. -

Region 10 Student Branches

Student Branches in R10 with Counselor & Chair contact August 2015 Par SPO SPO Name SPO ID Officers Full Name Officers Email Address Name Position Start Date Desc Australian Australian Natl Univ STB08001 Chair Miranda Zhang 01/01/2015 [email protected] Capital Terr Counselor LIAM E WALDRON 02/19/2013 [email protected] Section Univ Of New South Wales STB09141 Chair Meng Xu 01/01/2015 [email protected] SB Counselor Craig R Benson 08/19/2011 [email protected] Bangalore Acharya Institute of STB12671 Chair Lachhmi Prasad Sah 02/19/2013 [email protected] Section Technology SB Counselor MAHESHAPPA HARAVE 02/19/2013 [email protected] DEVANNA Adichunchanagiri Institute STB98331 Counselor Anil Kumar 05/06/2011 [email protected] of Technology SB Amrita School of STB63931 Chair Siddharth Gupta 05/03/2005 [email protected] Engineering Bangalore Counselor chaitanya kumar 05/03/2005 [email protected] SB Amrutha Institute of Eng STB08291 Chair Darshan Virupaksha 06/13/2011 [email protected] and Mgmt Sciences SB Counselor Rajagopal Ramdas Coorg 06/13/2011 [email protected] B V B College of Eng & STB62711 Chair SUHAIL N 01/01/2013 [email protected] Tech, Vidyanagar Counselor Rajeshwari M Banakar 03/09/2011 [email protected] B. M. Sreenivasalah STB04431 Chair Yashunandan Sureka 04/11/2015 [email protected] College of Engineering Counselor Meena Parathodiyil Menon 03/01/2014 [email protected] SB BMS Institute of STB14611 Chair Aranya Khinvasara 11/11/2013 [email protected] -

Inoperative Sb

INOPERATIVE SB ACCOUNTS SL NO ACCOUNT NUMBER CUSTOMER NAME 1 100200000032 SURESH T R 2 100200000133 NAVEEN H N * 3 100200000189 BALACHARI N M * 4 100200000202 JAYASIMHA B K 5 100200000220 SRIVIDHYA R 6 100200000225 GURURAJ C S * 7 100200000236 VASUDHA Y AITHAL * 8 100200000262 MUNICHANDRA M * 9 100200000269 VENKOBA RAO K R 10 100200000272 VIMALA H S 11 100200000564 PARASHURAMA SHARMA V * 12 100200000682 RAMDAS B S * 13 100200000715 SHANKARANARAYANA RAO T S 14 100200000752 M/S.VIDHYANIDHI - K.S.C.B.G.O. * 15 100200000768 SESHAPPA R N 16 100200000777 SHIVAKUMAR N * 17 100200000786 RAMYA VIJAY 18 100200000876 GIRIRAJ G R 19 100200000900 LEELAVATHI C S 20 100200000926 SARASWATHI A S * 21 100200001019 NAGENDRA PRASAD S 22 100200001037 BHANUPRAKASHA H V * 23 100200001086 GURU MURTHY K R * 24 100200001109 VANISHREE V S * 25 100200001183 VEENA SURESH * 26 100200001207 KRISHNA MURTHY Y N 27 100200001223 M/S.VACHAN ENTERPRISES * 28 100200001250 DESHPANDE M R 29 100200001272 ARJUN DESHPANDE * 30 100200001305 PRASANNA KUMAR S 31 100200001333 CHANDRASHEKARA H R 32 100200001401 KUMAR ARAGAM 33 100200001472 JAYALAKSMAMMA N * 34 100200001499 MOHAN RAO K * 35 100200001517 LEELA S JAIN 36 100200001523 MANJUNATH S BHAT 37 100200001557 SATYANARAYANA A * 1 38 100200001559 SHARADAMMA S * 39 100200001588 RAGHOTHAMA R * 40 100200001589 SRIDHARA RAO B S * 41 100200001597 SUBRAMANYA K N * 42 100200001635 SIMHA V N * 43 100200001656 SUMA PRAKASH 44 100200001679 INDIRESHA T V * 45 100200001691 AJAY H A 46 100200001718 VISHWANATH K N 47 100200001733 SREEKANTA MURTHY -

“Jejuri”: Faith and Scepticism

“JEJURI”: FAITH AND SCEPTICISM DR. JADHAV PRADEEP V. M. S. S. Arts College, Tirthpuri, Tal. Ghansawangi Dist. Jalna (MS) INDIA Oscillates between faith and skepticism is one of the dominant theme in "Jejuri" a collection of poem. Arun Kolatkar wrote the poem about Jejuri is a small town in western Maharashtra, situated at a distance about thirty miles from Pune. It is we known for its god Khandoba. The poet gave to his poem the title "Jejuri". But the most important aspect of his writing this poem is the faith, which the people of Maharashtra have, in the miraculous powers of Khandoba. This god is worshiped not only from different part of Maharashtra but also other part of India. The devotees go there worship the deity and effort to placate him to win his favor. But Kolatkar has not written the poem "Jejuri" to celebrate this god or to pay his personal tribute and homage. INTRODUCTION In fact he does not even fully believe in idol-worship of the worship of god in Jejuri. He believes this worship to be kind of superstition though he does not openly say so anywhere in the poem. Although the attitude of unbelief, or at least of skepticism, predominates in the poem. Yet some critics are of the view that his vision of Khandoba worship has a positive aspect to it. In this regard we can quote by R. Parthasarthy “In reality, however, the poem oscillates between faith and skepticism in a tradition that has run its course."1 It is clear that the poem, "Jejuri", depicts a direct and unflinching attitude of denial and disbelief. -

Indian Angles

Introduction The Asiatic Society, Kolkata. A toxic blend of coal dust and diesel exhaust streaks the façade with grime. The concrete of the new wing, once a soft yellow, now is dimmed. Mold, ever the enemy, creeps from around drainpipes. Inside, an old mahogany stair- case ascends past dusty paintings. The eighteenth-century fathers of the society line the stairs, their white linen and their pale skin yellow with age. I have come to sue for admission, bearing letters with university and government seals, hoping that official papers of one bureaucracy will be found acceptable by an- other. I am a little worried, as one must be about any bureaucratic encounter. But the person at the desk in reader services is polite, even friendly. Once he has enquired about my project, he becomes enthusiastic. “Ah, English language poetry,” he says. “Coleridge. ‘Oh Lady we receive but what we give . and in our lives alone doth nature live.’” And I, “Ours her wedding garment, ours her shroud.” And he, “In Xanadu did Kublai Khan a stately pleasure dome decree.” “Where Alf the sacred river ran,” I say. And we finish together, “down to the sunless sea.” I get my reader’s pass. But despite the clerk’s enthusiasm, the Asiatic Society was designed for a different project than mine. The catalog yields plentiful poems—in manuscript, on paper and on palm leaves, in printed editions of classical works, in Sanskrit and Persian, Bangla and Oriya—but no unread volumes of English language Indian poetry. In one sense, though, I have already found what I need: that appreciation of English poetry I have encountered everywhere, among strangers, friends, and col- leagues who studied in Indian English-medium schools. -

A Hermeneutic Study of Bengali Modernism

Modern Intellectual History http://journals.cambridge.org/MIH Additional services for Modern Intellectual History: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here FROM IMPERIAL TO INTERNATIONAL HORIZONS: A HERMENEUTIC STUDY OF BENGALI MODERNISM KRIS MANJAPRA Modern Intellectual History / Volume 8 / Issue 02 / August 2011, pp 327 359 DOI: 10.1017/S1479244311000217, Published online: 28 July 2011 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S1479244311000217 How to cite this article: KRIS MANJAPRA (2011). FROM IMPERIAL TO INTERNATIONAL HORIZONS: A HERMENEUTIC STUDY OF BENGALI MODERNISM. Modern Intellectual History, 8, pp 327359 doi:10.1017/S1479244311000217 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/MIH, IP address: 130.64.2.235 on 25 Oct 2012 Modern Intellectual History, 8, 2 (2011), pp. 327–359 C Cambridge University Press 2011 doi:10.1017/S1479244311000217 from imperial to international horizons: a hermeneutic study of bengali modernism∗ kris manjapra Department of History, Tufts University Email: [email protected] This essay provides a close study of the international horizons of Kallol, a Bengali literary journal, published in post-World War I Calcutta. It uncovers a historical pattern of Bengali intellectual life that marked the period from the 1870stothe1920s, whereby an imperial imagination was transformed into an international one, as a generation of intellectuals born between 1885 and 1905 reinvented the political category of “youth”. Hermeneutics, as a philosophically informed study of how meaning is created through conversation, and grounded in this essay in the thought of Hans Georg Gadamer, helps to reveal this pattern. -

The House in South Asian Muslim Women's Early Anglophone Life

Binghamton University The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB) Graduate Dissertations and Theses Dissertations, Theses and Capstones 2016 The House in South Asian Muslim Women’s Early Anglophone Life-Writing And Novels Diviani Chaudhuri Binghamton University--SUNY, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://orb.binghamton.edu/dissertation_and_theses Part of the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Chaudhuri, Diviani, "The House in South Asian Muslim Women’s Early Anglophone Life-Writing And Novels" (2016). Graduate Dissertations and Theses. 13. https://orb.binghamton.edu/dissertation_and_theses/13 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations, Theses and Capstones at The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE HOUSE IN SOUTH ASIAN MUSLIM WOMEN’S EARLY ANGLOPHONE LIFE-WRITING AND NOVELS BY DIVIANI CHAUDHURI BA, Jadavpur University, 2008 MA, Binghamton University, 2010 DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature in the Graduate School of Binghamton University State University of New York 2016 © Copyright by Diviani Chaudhuri 2016 All Rights Reserved Accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature in -

Missing the Jobs for the Data Improvements

8 ISSUES AND INSIGHTS MUMBAI | THURSDAY 24 JANUARY 2019 > ister Sheila Dikshit to say, “I don’t want required to bring in a radical change and > CHINESE WHISPERS the ugly box in my drawing room”. to stimulate the market to provide choice 2003 redux The CAS politics was unfolding too of viewing”, Trai had said in 2004. close to the upcoming 2004 Lok Sabha The latest Trai order may not meet Trai's latest intervention in the cable and DTH market has created more elections and it had to end. The best the vision with which it started regulat- All in the family option before the government was to roll ing the broadcasting industry. For Nakul Nath's confusion than it has solved it back. It did that, while getting Trai to instance, growth and competition of (pictured) expand its role so that it could manage businesses could be stifled through the appearance the mess after the government-ordered way a broadcasting company would like broadcasting along with telecom. The diktat on à la carte pricing, as packaging in the social conditional access system or CAS went to do business, all hell has broken loose, first thing that Trai did was to cap prices holds the key to success in the broad- media and completely out of hand in 2003, this time threatening a blackout if the companies at the existing level, while saying it was casting industry where content offered with state the regulator itself has triggered a situa- in question don’t comply by February 1. a temporary measure.