Women in Indira Gandhi's India, 1975-1977

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

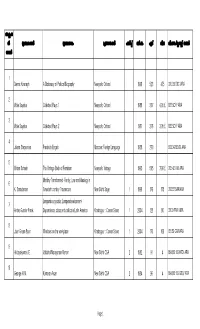

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

V. Aravindakshan 2.Xlsx

അക്സഷ ന് ഗര്ന്ഥകാരന് ഗര്ന്ഥനാമം പര്സാധകന് പതിപ്പ് വര്ഷംഏട്വിലവിഷയം/കല്ാസ്സ് നമ്പര് നമ്പര് 1 Dennis Kavnagh A Dictionary of Political Biography Newyork: Oxford 1998 523 475 320.092 DIC /ARA 2 Wole Soyinka Collected Plays 1 Newyork: Oxford 1988 307 4.95 £ 822 SOY/ ARA 3 Wole Soyinka Collected Plays 2 Newyork: Oxford 1987 276 3.95 £ 822 SOY/ ARA 4 Jelena Stepanova Frederick Engels Moscow: Foreign Language 1958 270 923.343 ENG/ ARA 5 Miriam Schneir The Vintage Book of Feminism Newyork: Vintage 1995 505 7.99 £ 305.42 VIN/ ARA 6 Matriliny Transformed -Family, Law and Ideology in K. Saradamoni Twenteth century Travancore New Delhi: Sage 1 1999 176 175 306.83 SAR/ARA 7 Lumpenbourgeoisle: Lumpendevelopment- Andre Gunder Frank Dependence, class and politics in Latin America Khabagpur : Corner Stone 1 2004 128 80 320.9 FRA/ ARA 8 Joan Green Baun Windows on the workplace Khabagpur : Corner Stone 1 2004 170 100 651.59 GRA/ARA 9 Hridayakumari. E. Vallathol Narayanan Menon New Delhi: CSA 2 1982 91 4 894.812 109 HRD/ ARA 10 George. K.M. Kumaran Asan New Delhi: CSA 2 1984 96 4 894.812 109 GEO/ ARA Page 1 11 Tharakan. K.M. M.P. Paul New Delhi: CSA 1 1985 96 4 894.812 109 THA/ ARA 12 335.43 AJI/ARA Ajit Roy Euro-Communism' An Analytical story Calcutta: Pearl 88 10 13 801.951 MAC/ARA Archi Bald Macleish Poetry and Experience Australia: Penguin Books 1960 187 Alien Homage' -Edward Thompson and 14 891.4414 THO/ARA E.P. Thompson Rabindranath Tagore New Delhi : Oxford 2 1998 175 275 15 894.812309 VIS/ARA R.Viswanathan Pottekkatt New Delhi: CSA 1 1998 60 5 16 891.73 CHE/ARA A.P. -

Marathi Osmania University, Hyderabad M.A

Osmania University Hyderabad, Telangana DEPARTMENT OF MARATHI OSMANIA UNIVERSITY, HYDERABAD M.A. (PREVIOUS) MARATHI CBCS SYLLABUS SEMESTER I PAPER I MADHYAYUGEEN MARATHI SAHITYA ( Credits : 5 ) (Hours : 5) Unit I : Prachin Marathi Sahityache Swaroop ani Vikas : Sant Dnyaneshwar, Namdev, Eknath, Tukaram Yanche Kavya ani tatwadnyan, Mahanubhav wa Bakhar Wangmay Unit II Leela Charitra Ekank : Chakradharanche Vyaktichitran,Mahanubhavachi Lekhanshailee Wa vaishisthye. Unit III Dnyaneshwari Adhyay Navava : Dnyaneshwaritil tatwadnyan wa Kavya Soundrya. Unit IV Tukaramache Nivdak Abhang : Abhangatoon vyakta honare bhav, Adhyatma wa Kavya Soundrya. Unit V Adnyapatra : Adnyapatratil Shivajichi Rajaneeti wa Rananeeti, BakharichiBhashashailee. Reference : Books 1 Prachin Marathi Wangmayachga Itihaas – P.N. Joshi, Venus, Prakashan, Pune 2 Sant Sahitya Darshan – Usha Deshmukh, Snehwardhan Prakshan, Pune 3 Dnyanadev wa Namdev – S. N. Pendse – Continental Prakshan, Pune 4 Arupache Roop – L. N. Jog 5 Mahanubhaviya Marathi Wangmay – Y. K. Deshpande 6 Prachin Marathi Wangmayche Swaroop – H. S. Shenolikar – Moghe Prakashan 7 Mahanubhavpanth wa tyache Wangmay – S. G. Tulpule 8 Marathi Sahityatil Madura Bhakti - P.N. Joshi, Venus, Prakashan, Pune 9 Marathi Bakhar – H. V. Herwadkar 10 Leelacharitra Ekank – H.S. Shenolikar, Moghe Prakshan, Pune 11 Dnyaneshwari Adhyaya Navava – Ed. M. N. Adavant, B. Khandekar, Anmol Pra. ,Pune 12 Tukaramache Niwadak Abhang – Ed. P. N. Joshi, Snehwardhan Prakshan, Pune 13 Adnyapatra – Ed S. G. Tulpule Osmania University Hyderabad, Telangana DEPARTMENT OF MARATHI OSMANIA UNIVERSITY, HYDERABAD M.A. (PREVIOUS) MARATHI CBCS SYLLABUS SEMESTER I PAPER II KAVYA SHASTRA (Credits : 5)( Hours : 5 ) Unit I Kavya Lakshan : Kavyache Swaroop , Vyapti, Vyakhya. Unit II Kavya Prayojan Prachin, Adhunik wa Pashchatya Prayojane. Unit III Kavya Nirmitichi Vividh Karne : Nirmitichya Shakti,Pratibha,Kalpanashakti,Sphurti ani Sankalpana. -

Growing Cleavages in India? Evidence from the Changing Structure of Electorates, 1962-2014

WID.world WORKING PAPER N° 2019/05 Growing Cleavages in India? Evidence from the Changing Structure of Electorates, 1962-2014 Abhijit Banerjee Amory Gethin Thomas Piketty March 2019 Growing Cleavages in India? Evidence from the Changing Structure of Electorates, 1962-2014 Abhijit Banerjee, Amory Gethin, Thomas Piketty* January 16, 2019 Abstract This paper combines surveys, election results and social spending data to document the long-run evolution of political cleavages in India. From a dominant- party system featuring the Indian National Congress as the main actor of the mediation of political conflicts, Indian politics have gradually come to include a number of smaller regionalist parties and, more recently, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). These changes coincide with the rise of religious divisions and the persistence of strong caste-based cleavages, while education, income and occupation play little role (controlling for caste) in determining voters’ choices. We find no evidence that India’s new party system has been associated with changes in social policy. While BJP-led states are generally characterized by a smaller social sector, switching to a party representing upper castes or upper classes has no significant effect on social spending. We interpret this as evidence that voters seem to be less driven by straightforward economic interests than by sectarian interests and cultural priorities. In India, as in many Western democracies, political conflicts have become increasingly focused on identity and religious-ethnic conflicts -

Annual Report 2014 - 2015 Ministry of Culture Government of India

ANNUAL REPORT 2014 - 2015 MINISTRY OF CULTURE GOVERNMENT OF INDIA Annual Report 2014-15 1 Ministry of Culture 2 Detail from Rani ki Vav, Patan, Gujarat, A World Heritage Site Annual Report 2014-15 CONTENTS 1. Ministry of Culture - An Overview – 5 2. Tangible Cultural Heritage 2.1 Archaeological Survey of India – 11 2.2 Museums – 28 2.2a National Museum – 28 2.2b National Gallery of Modern Art – 31 2.2c Indian Museum – 37 2.2d Victoria Memorial Hall – 39 2.2e Salar Jung Museum – 41 2.2f Allahabad Museum – 44 2.2g National Council of Science Museum – 46 2.3 Capacity Building in Museum related activities – 50 2.3a National Museum Institute of History of Art, Conservation and Museology – 50 2.3.b National Research Laboratory for conservation of Cultural Property – 51 2.4 National Culture Fund (NCF) – 54 2.5 International Cultural Relations (ICR) – 57 2.6 UNESCO Matters – 59 2.7 National Missions – 61 2.7a National Mission on Monuments and Antiquities – 61 2.7b National Mission for Manuscripts – 61 2.7c National Mission on Libraries – 64 2.7d National Mission on Gandhi Heritage Sites – 65 3. Intangible Cultural Heritage 3.1 National School of Drama – 69 3.2 Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts – 72 3.3 Akademies – 75 3.3a Sahitya Akademi – 75 3.3b Lalit Kala Akademi – 77 3.3c Sangeet Natak Akademi – 81 3.4 Centre for Cultural Resources and Training – 85 3.5 Kalakshetra Foundation – 90 3.6 Zonal cultural Centres – 94 3.6a North Zone Cultural Centre – 95 3.6b Eastern Zonal Cultural Centre – 95 3.6c South Zone Cultural Centre – 96 3.6d West Zone Cultural Centre – 97 3.6e South Central Zone Cultural Centre – 98 3.6f North Central Zone Cultural Centre – 98 3.6g North East Zone Cultural Centre – 99 Detail from Rani ki Vav, Patan, Gujarat, A World Heritage Site 3 Ministry of Culture 4. -

Items-In-United Nations Associations (Unas) in the World

UN Secretariat Item Scan - Barcode - Record Title Page 14 Date 21/06/2006 Time 11:29:23 AM S-0990-0002-07-00001 Expanded Number S-0990-0002-07-00001 Items-in-United Nations Associations (UNAs) in the World Date Created 22/12/1973 Record Type Archival Item Container S-0990-0002: United Nations Emergency and Relief Operations Print Name of Person Submit Image Signature of Person Submit *RA/IL/SG bf .KH/ PMG/ T$/ MP cc: SG 21 October 75 X. Lehmann/sg 38O2 87S EOSG OMNIPRESS LONDON (ENGLAND) \ POPOVIC REFERENCE YOUR 317 TO HENUIG, MESSAGE PROM SECGEH ON ANNIVERSARY OF WINSCHOTElJt UK ^TOWKf WAS MAILED BY US OCTOBER 17 MSD CABLED TO DE BOER BY NETHERLANDS PERMANENT MISSION DODAY AS TELEPHONE MESSAGE FROM SECGEN NOT POSSIBLE. REGARDS, AHMED Rafeeuddin Ahmed ti at r >»"• f REFCREHCX & SEPfSMiS!? LETTS8 ' AS80CXATXOK COPIES Y0BR OFFICE PB0P8SW f © ¥IJI$0H0TE8 IfH 10^8* &fJT£H AMBASSADOR KADFE1AW UNDSETAKIMG sur THEY ®0^i APPRI OIATI sn©Hf SABLS& SECSSH es OS WITS ®&M XKSTlATS9ff GEREf&DtES LAST 88 BAY IF M01E COKVEltXEtir atrEETx ti&s TIKI at$« BEKALr« — -— S • Sit ' " 9, 20 osfc&fee* This is the text of the Secretary-General's message sent to Ms. Gerry M. de Boer on October £ waa very interested to learn of your plans to celebsrate United Nations Bay on S4 October, and the first anniversary of Winschoten ti«H. Town. I would like to congratulate the Hetlierlanfis United Nations Association and the Winschoten Committee on this imaginative programme. It is particularly rewarding and encouraging when citizens involve themselves positively ani constructively in the concerns of the United Nations. -

IBPS PO 2016 Capsule by Affairscloud.Pdf

AC Booster IBPS PO 2016 Hello Dear AC Aspirants, Here we are providing best AC Booster for IBPS PO 2016 keeping in mind of upcoming IBPS PO exam which cover General Awareness section . PLS find out the links of AffairsCloud Exam Capsule and all also the link of 6 months AC monthly capsules + pocket capsules and Static Capsule which cover almost all questions of GA section of IBPS PO. All the best for IBPS PO Exam with regards from AC Team. Kindly Check Other Capsules • Afffairscloud Exam Capsule • Current Affairs Study Capsule • Current Affairs Pocket Capsule • Static General Knowledge capsule Help: If You Satisfied with our Capsule mean kindly donate some amount to BoscoBan.org (Facebook.com/boscobengaluru ) or Kindly Suggest this site to our family members & friends !!! AC Booster – IBPS PO 2016 Table of Contents BANKING & FINANCIAL AWARENESS .................................................................................................. 2 INDIAN AFFAIRS ......................................................................................................................................... 26 INTERNATIONAL NEWS ........................................................................................................................... 50 NATIONAL & INTERNATIONAL AWARDS .......................................................................................... 67 IMPORTANT APPOINTMENTS ................................................................................................................ 72 BUSINESS ..................................................................................................................................................... -

July 2021.Cdr

St. Norbert Campus Chronicles Vol -2, Issue 2 St. Norbert School, CBSE Affliation No: 831041, Chowhalli, T. Narasipura - 571124 July - 2021 World Day for International Justice - By Amruth world as part of an effort to recognize fact that on the same day the year 2010 decided to celebrate July the system of international criminal International Criminal Court was 17 as World Day for International justice and for the people to pay established. The International Justice. In addition, 'Social Justice in attention to serious crimes happening Criminal Court which was the Digital Economy' has been around the world. This day is also established on this day along with adopted as this year's theme to known as international criminal ratification of the Rome Statute is a celebrate the World Day for "True peace is not merely the absence justice day, which aims at the mechanism to bring to book grave International Justice. The theme of of tension but it is the presence of importance of bringing justice to crimes and ensure harsh punishment Social Justice in the Digital Justice", famous quotation by Martin people against crimes, wars and for criminals resorting to crimes at Economy also points to the large Luther King which means that genocides. The world celebrates the the international level. Apart from digital divide between haves and genuine peace requires the presence World Day for International Justice paying homage to the people and have nots. The topic is extremely of Justice, but the absence of conflict celebrating the virtues of justice organisations committed to the cause relevant for this year as with the swift and violence. -

Global Feminisms: Interview Transcripts: India Language: English

INDIA Global Feminisms: Comparative Case Studies of Women’s Activism and Scholarship Interview Transcripts: India Language: English Interview Transcripts: India Contents Acknowledgments 3 Shahjehan Aapa 4 Flavia Agnes 23 Neera Desai 48 Ima Thokchom Ramani Devi 67 Mahasweta Devi 83 Jarjum Ete 108 Lata Pratibha Madhukar 133 Mangai 158 Vina Mazumdar 184 D. Sharifa 204 2 Acknowledgments Global Feminisms: Comparative Case Studies of Women’s Activism and Scholarship was housed at the Institute for Research on Women and Gender at the University of Michigan (UM) in Ann Arbor, Michigan. The project was co-directed by Abigail Stewart, Jayati Lal and Kristin McGuire. The China site was housed at the China Women’s University in Beijing, China and directed by Wang Jinling and Zhang Jian, in collaboration with UM faculty member Wang Zheng. The India site was housed at the Sound and Picture Archives for Research on Women (SPARROW) in Mumbai, India and directed by C.S. Lakshmi, in collaboration with UM faculty members Jayati Lal and Abigail Stewart. The Poland site was housed at Fundacja Kobiet eFKa (Women’s Foundation eFKa) in Krakow, Poland and directed by Slawka Walczewska, in collaboration with UM faculty member Magdalena Zaborowska. The U.S. site was housed at the Institute for Research on Women and Gender at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Michigan and directed by UM faculty member Elizabeth Cole. Graduate student interns on the project included Nicola Curtin, Kim Dorazio, Jana Haritatos, Helen Ho, Julianna Lee, Sumiao Li, Zakiya Luna, Leslie Marsh, Sridevi Nair, Justyna Pas, Rosa Peralta, Desdamona Rios and Ying Zhang. -

BEST U.S. COLLEGES–AND the ONES to AVOID/Pg.82 RNI REG

BEST U.S. COLLEGES–AND THE ONES TO AVOID/Pg.82 RNI REG. NO. MAHENG/2009/28102 INDIA PRICEPRICE RSRS. 100100. AUGUST 2323, 2013 FORBES INDIA INDEPENDENCESpecial Issue Day VOLUME 5 ISSUE 17 TIME TO Pg.37 INDIA AUGUST 23, 2013 BRE A K INDEPENDENCE DAY SPECIAL FREThe boundaries of E economic, political and individual freedom need to be extended www.forbesindia.com LETTER FROM THE EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Towards Greater Freedom or a country that became politically free in 1947 and took a stab at economic freedom in 1991, the script in 2013 could not have been worse: An economy going downhill, a currency into free fall, and a widespread Ffeeling of despondency and frustration. A more full-blooded embrace of markets should have brought corruption down and increased competition for the benefi t of customers and citizens alike. But that was not the path we took over the last decade. An expanding pie should have provided adequate resources for off ering safety nets to the really poor even while leaving enough with the exchequer to fund public goods. But India is currently eating the seedcorn of future growth with mindless social spending. Corruption has scaled new heights, politicians have been found hand-in-glove with businessmen to hijack state resources for private ends, and a weakened state is opting for even harsher laws and an INDIA ever-expanding system of unaff ordable doles to maintain itself in power. Politicians have raided the treasury for private purposes, and businessmen fi nd more profi t in rent-seeking behaviour than in competing fairly in the marketplace. -

The First National Conference Government in Jammu and Kashmir, 1948-53

THE FIRST NATIONAL CONFERENCE GOVERNMENT IN JAMMU AND KASHMIR, 1948-53 THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF Doctor of Philosophy IN HISTORY BY SAFEER AHMAD BHAT Maulana Azad Library, Aligarh Muslim University UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF PROF. ISHRAT ALAM CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2019 CANDIDATE’S DECLARATION I, Safeer Ahmad Bhat, Centre of Advanced Study, Department of History, certify that the work embodied in this Ph.D. thesis is my own bonafide work carried out by me under the supervision of Prof. Ishrat Alam at Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh. The matter embodied in this Ph.D. thesis has not been submitted for the award of any other degree. I declare that I have faithfully acknowledged, given credit to and referred to the researchers wherever their works have been cited in the text and the body of the thesis. I further certify that I have not willfully lifted up some other’s work, para, text, data, result, etc. reported in the journals, books, magazines, reports, dissertations, theses, etc., or available at web-sites and included them in this Ph.D. thesis and cited as my own work. The manuscript has been subjected to plagiarism check by Urkund software. Date: ………………… (Signature of the candidate) (Name of the candidate) Certificate from the Supervisor Maulana Azad Library, Aligarh Muslim University This is to certify that the above statement made by the candidate is correct to the best of my knowledge. Prof. Ishrat Alam Professor, CAS, Department of History, AMU (Signature of the Chairman of the Department with seal) COURSE/COMPREHENSIVE EXAMINATION/PRE- SUBMISSION SEMINAR COMPLETION CERTIFICATE This is to certify that Mr. -

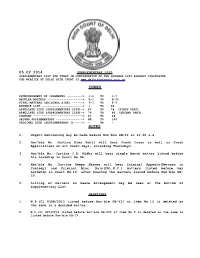

05.02.2014 Notes

05.02.2014 SUPPLEMENTARY LIST SUPPLEMENTARY LIST FOR TODAY IN CONTINUATION OF THE ADVANCE LIST ALREADY CIRCULATED. THE WEBSITE OF DELHI HIGH COURT IS www.delhihighcourt.nic.in INDEX PRONOUNCEMENT OF JUDGMENTS ---------> J-1 TO J-7 REGULAR MATTERS --------------------> R-1 TO R-51 FINAL MATTERS (ORIGINAL SIDE) ------> F-1 TO F-5 ADVANCE LIST -----------------------> 1 TO 66 APPELLATE SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY LIST)-> 67 TO 78 (FIRST PART) APPELLATE SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY LIST)-> 79 TO 86 (SECOND PART) COMPANY ----------------------------> 87 TO 88 SECOND SUPPLEMENTARY ---------------> 89 TO 104 ORIGINAL SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY I)-----> - TO - NOTES 1. Urgent mentioning may be made before Hon'ble DB-II at 10.30 a.m. 2. Hon'ble Ms. Justice Hima Kohli will hear Fresh Cases as well as Fresh Applications on all Court days, including Thursdays. 3. Hon'ble Mr. Justice J.R. Midha will hear single bench matter listed before his Lordship in Court No.36. 4. Hon'ble Ms. Justice Deepa Sharma will hear Criminal Appeals(Persons in Custody) and Criminal Misc. Main(CRL.M.C.) matters listed before her Lordship in Court No.16; after hearing the matters listed before Hon'ble DB- IV. 5. Listing of matters on Leave Arrangement may be seen at the bottom of Supplementary List. DELETIONS 1. W.P.(C) 6358/2013 listed before Hon'ble DB-VII at item No.13 is deleted as the same is a decided matter. 2. W.P.(C) 947/2013 listed before Hon'ble DB-VII at item No.9 is deleted as the same is listed before Hon'ble DB-IV.