Single-Cell Analysis of CD4 T Cells in Type 1 Diabetes: from Mouse to Man, How to Perform Mechanistic Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Role of IL-4 Receptor &Alpha

Role of IL-4 receptor a–positive CD41 T cells in chronic airway hyperresponsiveness Frank Kirstein, PhD, Natalie E. Nieuwenhuizen, PhD,* Jaisubash Jayakumar, PhD, William G. C. Horsnell, PhD, and Frank Brombacher, PhD Cape Town, South Africa, and Berlin, Germany Background: TH2 cells and their cytokines are associated with IL-17–producing T cells and, consequently, increased airway allergic asthma in human subjects and with mouse models of neutrophilia. allergic airway disease. IL-4 signaling through the IL-4 receptor Conclusion: IL-4–responsive T helper cells are dispensable for 1 a (IL-4Ra) chain on CD4 T cells leads to TH2 cell acute OVA-induced airway disease but crucial in maintaining differentiation in vitro, implying that IL-4Ra–responsive CD41 chronic asthmatic pathology. (J Allergy Clin Immunol T cells are critical for the induction of allergic asthma. However, 2016;137:1852-62.) mechanisms regulating acute and chronic allergen-specific T 2 H Key words: responses in vivo remain incompletely understood. TH2 cell, acute allergic airway disease, chronic asthma, Objective: This study defines the requirements for IL-4Ra– cytokine receptors, IL-4, IL-13, gene-deficient mice responsive CD41 T cells and the IL-4Ra ligands IL-4 and IL-13 in the development of allergen-specific TH2 responses during the Allergic asthma is a chronic inflammatory disease of the airways onset and chronic phase of experimental allergic airway disease. characterized by an inappropriate immune response to harmless Methods: Development of acute and chronic ovalbumin environmental antigens. T 2 cells regulate adaptive immune 1 H (OVA)–induced allergic asthma was assessed weekly in CD4 T responses to allergens, and their presence correlates with disease 2 cell–specific IL-4Ra–deficient BALB/c mice (LckcreIL-4Ra /lox) symptoms in human subjects and mice.1 IL-4 plays a crucial role and respective control mice in the presence or absence of IL-4 in the in vitro and in vivo differentiation of TH2 cells, suggesting or IL-13. -

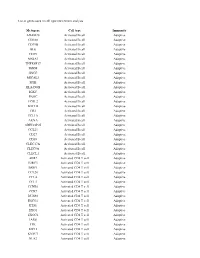

List of Genes Used in Cell Type Enrichment Analysis

List of genes used in cell type enrichment analysis Metagene Cell type Immunity ADAM28 Activated B cell Adaptive CD180 Activated B cell Adaptive CD79B Activated B cell Adaptive BLK Activated B cell Adaptive CD19 Activated B cell Adaptive MS4A1 Activated B cell Adaptive TNFRSF17 Activated B cell Adaptive IGHM Activated B cell Adaptive GNG7 Activated B cell Adaptive MICAL3 Activated B cell Adaptive SPIB Activated B cell Adaptive HLA-DOB Activated B cell Adaptive IGKC Activated B cell Adaptive PNOC Activated B cell Adaptive FCRL2 Activated B cell Adaptive BACH2 Activated B cell Adaptive CR2 Activated B cell Adaptive TCL1A Activated B cell Adaptive AKNA Activated B cell Adaptive ARHGAP25 Activated B cell Adaptive CCL21 Activated B cell Adaptive CD27 Activated B cell Adaptive CD38 Activated B cell Adaptive CLEC17A Activated B cell Adaptive CLEC9A Activated B cell Adaptive CLECL1 Activated B cell Adaptive AIM2 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive BIRC3 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive BRIP1 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive CCL20 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive CCL4 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive CCL5 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive CCNB1 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive CCR7 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive DUSP2 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive ESCO2 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive ETS1 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive EXO1 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive EXOC6 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive IARS Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive ITK Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive KIF11 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive KNTC1 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive NUF2 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive PRC1 Activated -

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Demonstrates the Molecular and Cellular Reprogramming of Metastatic Lung Adenocarcinoma

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16164-1 OPEN Single-cell RNA sequencing demonstrates the molecular and cellular reprogramming of metastatic lung adenocarcinoma Nayoung Kim 1,2,3,13, Hong Kwan Kim4,13, Kyungjong Lee 5,13, Yourae Hong 1,6, Jong Ho Cho4, Jung Won Choi7, Jung-Il Lee7, Yeon-Lim Suh8,BoMiKu9, Hye Hyeon Eum 1,2,3, Soyean Choi 1, Yoon-La Choi6,10,11, Je-Gun Joung1, Woong-Yang Park 1,2,6, Hyun Ae Jung12, Jong-Mu Sun12, Se-Hoon Lee12, ✉ ✉ Jin Seok Ahn12, Keunchil Park12, Myung-Ju Ahn 12 & Hae-Ock Lee 1,2,3,6 1234567890():,; Advanced metastatic cancer poses utmost clinical challenges and may present molecular and cellular features distinct from an early-stage cancer. Herein, we present single-cell tran- scriptome profiling of metastatic lung adenocarcinoma, the most prevalent histological lung cancer type diagnosed at stage IV in over 40% of all cases. From 208,506 cells populating the normal tissues or early to metastatic stage cancer in 44 patients, we identify a cancer cell subtype deviating from the normal differentiation trajectory and dominating the metastatic stage. In all stages, the stromal and immune cell dynamics reveal ontological and functional changes that create a pro-tumoral and immunosuppressive microenvironment. Normal resident myeloid cell populations are gradually replaced with monocyte-derived macrophages and dendritic cells, along with T-cell exhaustion. This extensive single-cell analysis enhances our understanding of molecular and cellular dynamics in metastatic lung cancer and reveals potential diagnostic and therapeutic targets in cancer-microenvironment interactions. 1 Samsung Genome Institute, Samsung Medical Center, Seoul 06351, Korea. -

B Cell Checkpoints in Autoimmune Rheumatic Diseases

REVIEWS B cell checkpoints in autoimmune rheumatic diseases Samuel J. S. Rubin1,2,3, Michelle S. Bloom1,2,3 and William H. Robinson1,2,3* Abstract | B cells have important functions in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases, including autoimmune rheumatic diseases. In addition to producing autoantibodies, B cells contribute to autoimmunity by serving as professional antigen- presenting cells (APCs), producing cytokines, and through additional mechanisms. B cell activation and effector functions are regulated by immune checkpoints, including both activating and inhibitory checkpoint receptors that contribute to the regulation of B cell tolerance, activation, antigen presentation, T cell help, class switching, antibody production and cytokine production. The various activating checkpoint receptors include B cell activating receptors that engage with cognate receptors on T cells or other cells, as well as Toll-like receptors that can provide dual stimulation to B cells via co- engagement with the B cell receptor. Furthermore, various inhibitory checkpoint receptors, including B cell inhibitory receptors, have important functions in regulating B cell development, activation and effector functions. Therapeutically targeting B cell checkpoints represents a promising strategy for the treatment of a variety of autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Antibody- dependent B cells are multifunctional lymphocytes that contribute that serve as precursors to and thereby give rise to acti- cell- mediated cytotoxicity to the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases -

Cd4/Cd8 Panel, Blood

Lab Dept: Flow and Immunology Test Name: CD4/CD8 PANEL, BLOOD General Information Lab Order Codes: C48P Synonyms: Helper/Suppressor Ratio; T- cells; T-cell subsets; T-cell phenotyping See also: Immune Status Panel and Comprehensive Immune Status Panel CPT Codes: 86359 – T cells, total count 86360 – T cells; absolute CD4 and CD8 count, including ratio Test Includes: CD4(CD3+) and CD8(CD3+) relative percentages, absolute values and a calculated Helper/Suppressor ratio. Logistics Test Indications: This is a minimal antibody panel to monitor immune status. Lab Testing Sections: Flow Cytometry Phone Numbers: MIN Lab: 612-813-6280 STP Lab: 651-220-6550 Test Availability: 3 times weekly determined by volume. Transport collected specimen immediately to Flow Cytometry. Routine testing is not available on weekends or holidays. Therefore, specimens cannot be used if drawn the day before a 3 day weekend such as Memorial Day, Labor Day or major holiday that falls on a Monday or Friday. Turnaround Time: 1 – 3 days Special Instructions: See Test Availability Specimen Specimen Type: Whole blood Container: Lavender top (EDTA) tube Draw Volume: 2 mL blood in a 2 mL Lavender (EDTA) tube Minimum volume: 0.5 mL in an EDTA microtainer Collection: Routine venipuncture Special Processing: Keep sample at room temperature and forward promptly to the laboratory. Do not centrifuge, refrigerate, or freeze sample. Patient Preparation: None Sample Rejection: Specimens will not be processed that are clotted; hemolyzed; greater than 72 hours old; collected in the wrong tube type (0.5 mL in a 2 mL tube), or that have been held or handled at a temperature other than room temperature Interpretive Reference Range: Age-dependant reference ranges provided with results. -

Rational Design of a CD4 Mimic That Inhibits HIV-1 Entry and Exposes Cryptic Neutralization Epitopes

RESEARCH ARTICLE Rational design of a CD4 mimic that inhibits HIV-1 entry and exposes cryptic neutralization epitopes Loïc Martin1, François Stricher1, Dorothée Missé2, Francesca Sironi3, Martine Pugnière4, Philippe Barthe5, Rafael Prado-Gotor5, Isabelle Freulon1, Xavier Magne2, Christian Roumestand5, André Ménez1, Paolo Lusso3, Francisco Veas2, and Claudio Vita1* Published online 16 December 2002; doi:10.1038/nbt768 The conserved surfaces of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 envelope involved in receptor binding represent potential targets for the development of entry inhibitors and neutralizing antibodies. Using structural information on a CD4-gp120-17b antibody complex, we have designed a 27-amino acid CD4 mimic, CD4M33, that presents optimal interactions with gp120 and binds to viral particles and diverse HIV-1 envelopes with CD4-like affinity.This mini-CD4 inhibits infection of both immortalized and primary cells by HIV-1, including pri- http://www.nature.com/naturebiotechnology mary patient isolates that are generally resistant to inhibition by soluble CD4. Furthermore, CD4M33 pos- sesses functional properties of CD4, including the ability to unmask conserved neutralization epitopes of gp120 that are cryptic on the unbound glycoprotein. CD4M33 is a prototype of inhibitors of HIV-1 entry and, in complex with envelope proteins, a potential component of vaccine formulations, or a molecular target in phage display technology to develop broad-spectrum neutralizing antibodies. HIV-1 avoids the host immune surveillance by exposing -

Tethering IL2 to Its Receptor Il2rb Enhances Antitumor Activity and Expansion of Natural Killer NK92 Cells Youssef Jounaidi, Joseph F

Published OnlineFirst September 15, 2017; DOI: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-1007 Cancer Therapeutics, Targets, and Chemical Biology Research Tethering IL2 to Its Receptor IL2Rb Enhances Antitumor Activity and Expansion of Natural Killer NK92 Cells Youssef Jounaidi, Joseph F. Cotten, Keith W. Miller, and Stuart A. Forman Abstract IL2 is an immunostimulatory cytokine for key immune cells of IL2 and its receptor IL2Rb joined via a peptide linker (CIRB). including T cells and natural killer (NK) cells. Systemic IL2 NK92 cells expressing CIRB (NK92CIRB) were highly activated and supplementation could enhance NK-mediated immunity in a expanded indefinitely without exogenous IL2. When compared variety of diseases ranging from neoplasms to viral infection. with an IL2-secreting NK92 cell line, NK92CIRB were more acti- However, its systemic use is restricted by its serious side effects and vated, cytotoxic, and resistant to growth inhibition. Direct contact limited efficacy due to activation of T regulatory cells (Tregs). IL2 with cancer cells enhanced the cytotoxic character of NK92CIRB signaling is mediated through interactions with a multi-subunit cells, which displayed superior in vivo antitumor effects in mice. receptor complex containing IL2Ra, IL2Rb, and IL2Rg. Adult Overall, our results showed how tethering IL2 to its receptor natural killer (NK) cells express only IL2Rb and IL2Rg subunits IL2Rb eliminates the need for IL2Ra and IL2Rb, offering a and are therefore relatively insensitive to IL2. To overcome these new tool to selectively activate and empower immune therapy. limitations, we created a novel chimeric IL2-IL2Rb fusion protein Cancer Res; 77(21); 5938–51. Ó2017 AACR. Introduction in order for allogeneic NK cells to be effective, pretransfer lymphodepletion is required to reduce competition for growth Natural killer (NK) cells are lymphocytes endowed with the factors and cytokines (14, 15). -

Calcium-Mediated Shaping of Naive CD4 T-Cell Phenotype and Function

RESEARCH ARTICLE Calcium-mediated shaping of naive CD4 T-cell phenotype and function Vincent Guichard1,2, Nelly Bonilla1, Aure´ lie Durand1, Alexandra Audemard-Verger1, Thomas Guilbert1, Bruno Martin1, Bruno Lucas1†, Ce´ dric Auffray1†* 1Institut Cochin, Paris Descartes Universite´, CNRS UMR8104, INSERM U1016, Paris, France; 2Paris Diderot Universite´, Paris, France Abstract Continuous contact with self-major histocompatibility complex ligands is essential for the survival of naive CD4 T cells. We have previously shown that the resulting tonic TCR signaling also influences their fate upon activation by increasing their ability to differentiate into induced/ peripheral regulatory T cells. To decipher the molecular mechanisms governing this process, we here focus on the TCR signaling cascade and demonstrate that a rise in intracellular calcium levels is sufficient to modulate the phenotype of mouse naive CD4 T cells and to increase their sensitivity to regulatory T-cell polarization signals, both processes relying on calcineurin activation. Accordingly, in vivo calcineurin inhibition leads the most self-reactive naive CD4 T cells to adopt the phenotype of their less self-reactive cell-counterparts. Collectively, our findings demonstrate that calcium- mediated activation of the calcineurin pathway acts as a rheostat to shape both the phenotype and effector potential of naive CD4 T cells in the steady-state. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.27215.001 *For correspondence: Introduction [email protected] T-cell precursors originate in the bone-marrow and are educated in the thymus through processes † called positive and negative selections, which result in MHC-restriction and self-tolerance, respec- These authors contributed equally to this work tively (Stritesky et al., 2012). -

IL-7-Stimulated T Lymphocytes Correlated with Cell Cycle

IL-7Rα Gene Expression Is Inversely Correlated with Cell Cycle Progression in IL-7-Stimulated T Lymphocytes This information is current as Louise Swainson, Els Verhoeyen, François-Loïc Cosset and of October 1, 2021. Naomi Taylor J Immunol 2006; 176:6702-6708; ; doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.11.6702 http://www.jimmunol.org/content/176/11/6702 Downloaded from References This article cites 49 articles, 33 of which you can access for free at: http://www.jimmunol.org/content/176/11/6702.full#ref-list-1 http://www.jimmunol.org/ Why The JI? Submit online. • Rapid Reviews! 30 days* from submission to initial decision • No Triage! Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists • Fast Publication! 4 weeks from acceptance to publication *average by guest on October 1, 2021 Subscription Information about subscribing to The Journal of Immunology is online at: http://jimmunol.org/subscription Permissions Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html Email Alerts Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts The Journal of Immunology is published twice each month by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2006 by The American Association of Immunologists All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0022-1767 Online ISSN: 1550-6606. The Journal of Immunology IL-7R␣ Gene Expression Is Inversely Correlated with Cell Cycle Progression in IL-7-Stimulated T Lymphocytes1 Louise Swainson,2*†‡§ Els Verhoeyen,2¶ሻ# Franc¸ois-Loı¨c Cosset,¶ሻ# and Naomi Taylor3*†‡§ IL-7 plays a major role in T lymphocyte homeostasis and has been proposed as an immune adjuvant for lymphopenic patients. -

HIV-1) CD4 Receptor and Its Central Role in Promotion of HIV-1 Infection

MICROBIOLOGICAL REVIEWS, Mar. 1995, p. 63–93 Vol. 59, No. 1 0146-0749/95/$04.0010 Copyright q 1995, American Society for Microbiology The Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 (HIV-1) CD4 Receptor and Its Central Role in Promotion of HIV-1 Infection STEPHANE BOUR,* ROMAS GELEZIUNAS,† AND MARK A. WAINBERG* McGill AIDS Centre, Lady Davis Institute-Jewish General Hospital, and Departments of Microbiology and Medicine, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada H3T 1E2 INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................................................................................63 RETROVIRAL RECEPTORS .....................................................................................................................................64 Receptors for Animal Retroviruses ........................................................................................................................64 CD4 Is the Major Receptor for HIV-1 Infection..................................................................................................65 ROLE OF THE CD4 CORECEPTOR IN T-CELL ACTIVATION........................................................................65 Structural Features of the CD4 Coreceptor..........................................................................................................65 Interactions of CD4 with Class II MHC Determinants ......................................................................................66 CD4–T-Cell Receptor Interactions during T-Cell Activation -

Single Cell Transcriptomics of Regulatory T Cells Reveals Trajectories of Tissue Adaptation

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/217489; this version posted November 22, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Single cell transcriptomics of regulatory T cells reveals trajectories of tissue adaptation Authors: 1,2,a 1,a 3,4 7 Ricardo J Miragaia , Tomás Gomes , Agnieszka Chomka , Laura Jardine , Angela 8 3,4,5 1,9 1 3,4,6 Riedel , Ahmed N. Hegazy , Ida Lindeman , Guy Emerton , Thomas Krausgruber , 8 7 3,4 1,10,11,* Jacqueline Shields , Muzlifah Haniffa , Fiona Powrie , Sarah A. Teichmann Affiliations: 1 Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Wellcome Trust Genome Campus, Hinxton, UK 2 Centre of Biological Engineering, University of Minho, Braga, Portugal 3 Kennedy Institute of Rheumatology, Nuffield Department of Orthopaedics, Rheumatology and Musculoskeletal Sciences, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK 4 Translational Gastroenterology Unit, Experimental Medicine Division Nuffield Department of Clinical Medicine, University of Oxford, John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, UK 5 Current affiliation: Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, corporate member of Freie Universität Berlin, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, and Berlin Institute of Health, -

Expansions of Adaptive-Like NK Cells with a Tissue-Resident Phenotype in Human Lung and Blood

Expansions of adaptive-like NK cells with a tissue-resident phenotype in human lung and blood Demi Brownliea,1, Marlena Scharenberga,1, Jeff E. Moldb, Joanna Hårdb, Eliisa Kekäläinenc,d,e, Marcus Buggerta, Son Nguyenf,g, Jennifer N. Wilsona, Mamdoh Al-Amerih, Hans-Gustaf Ljunggrena, Nicole Marquardta,2,3, and Jakob Michaëlssona,2 aCenter for Infectious Medicine, Department of Medicine Huddinge, Karolinska Institutet, 14152 Stockholm, Sweden; bDepartment of Cell and Molecular Biology, Karolinska Institutet, 171 77 Stockholm, Sweden; cTranslational Immunology Research Program, University of Helsinki, 00014 Helsinki, Finland; dDepartment of Bacteriology and Immunology, University of Helsinki, 00014 Helsinki, Finland; eHelsinki University Central Hospital Laboratory, Division of Clinical Microbiology, Helsinki University Hospital, 00290 Helsinki, Finland; fDepartment of Microbiology, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104; gInstitute for Immunology, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104; and hThoracic Surgery, Department of Molecular Medicine and Surgery, Karolinska University Hospital, Karolinska Institutet, 171 76 Stockholm, Sweden Edited by Marco Colonna, Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, and approved January 27, 2021 (received for review August 18, 2020) Human adaptive-like “memory” CD56dimCD16+ natural killer (NK) We and others recently identified a subset of tissue-resident − cells in peripheral blood from cytomegalovirus-seropositive indi- CD49a+CD56brightCD16 NK cells in the human lung (14, 15). viduals have been extensively investigated in recent years and are The human lung is a frequent site of infection with viruses such currently explored as a treatment strategy for hematological can- as influenza virus and HCMV, as well as a reservoir for latent cers.