Don Quijote in English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Don Quixote and Legacy of a Caricaturist/Artistic Discourse

Don Quixote and the Legacy of a Caricaturist I Artistic Discourse Rupendra Guha Majumdar University of Delhi In Miguel de Cervantes' last book, The Tria/s Of Persiles and Sigismunda, a Byzantine romance published posthumously a year after his death in 1616 but declared as being dedicated to the Count of Lemos in the second part of Don Quixote, a basic aesthetie principIe conjoining literature and art was underscored: "Fiction, poetry and painting, in their fundamental conceptions, are in such accord, are so close to each other, that to write a tale is to create pietoríal work, and to paint a pieture is likewise to create poetic work." 1 In focusing on a primal harmony within man's complex potential of literary and artistic expression in tandem, Cervantes was projecting a philosophy that relied less on esoteric, classical ideas of excellence and truth, and more on down-to-earth, unpredictable, starkly naturalistic and incongruous elements of life. "But fiction does not", he said, "maintain an even pace, painting does not confine itself to sublime subjects, nor does poetry devote itself to none but epie themes; for the baseness of lífe has its part in fiction, grass and weeds come into pietures, and poetry sometimes concems itself with humble things.,,2 1 Quoted in Hans Rosenkranz, El Greco and Cervantes (London: Peter Davies, 1932), p.179 2 Ibid.pp.179-180 Run'endra Guha It is, perhaps, not difficult to read in these lines Cervantes' intuitive vindication of the essence of Don Quixote and of it's potential to generate a plural discourse of literature and art in the years to come, at multiple levels of authenticity. -

2022 Spain: Spanish in the Land of Don Quixote

Please see the NOTICE ON PROGRAM UPDATES at the bottom of this sample itinerary for details on program changes. Please note that program activities may change in order to adhere to COVID-19 regulations. SPAIN: Spanish in the Land of Don Quixote™ For more than a language course, travel to Toledo, Madrid & Salamanca - the perfect setting for a full Spanish experience in Castilla-La Mancha. OVERVIEW HIGHLIGHTS On this program you will travel to three cities in the heart of Spain, all ★ with rich histories that bring a unique taste of the country with each stop. Improve your Spanish through Start your journey in Madrid, the Spanish capital. Then head to Toledo, language immersion ★ where your Spanish immersion will truly begin and will make up the Walk the historic streets of Toledo, heart of your program experience. Journey west to Salamanca, where known as "the city of three you'll find the third oldest European university and Cervantes' alma cultures" ★ mater. Finally, if you opt to stay for our Homestay Extension, you will live Visit some of Madrid's oldest in Toledo for a week with a local family and explore Almagro, home to restaurants on a tapas tours ★ one of the oldest open air theaters in the world. Go kayaking on the Alto Tajo River ★ Help to run a summer English language camp for Spanish 14-DAY PROGRAM Tuition: $4,399 children Service Hours: 20 ★ Stay an extra week and live with a June 25 – July 8, 2022 Language Hours: 35 Spanish family to perfect your + 7-NIGHT HOMESTAY (OPTIONAL) Max Group Size: 32 Spanish language skills (Homestay July 8 - July 15 Age Range: 14-19 Add 10 service hours add-on only) Add 20 language hours Student-to-Staff Ratio: 8-to-1 Add $1,699 tuition Airport: MAD experienceGLA.com | +1 858-771-0645 | @GLAteens DAILY BREAKDOWN Actual schedule of activities will vary by program session. -

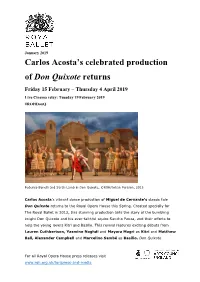

Don Quixote Press Release 2019

January 2019 Carlos Acosta’s celebrated production of Don Quixote returns Friday 15 February – Thursday 4 April 2019 Live Cinema relay: Tuesday 19 February 2019 #ROHDonQ Federico Bonelli and Sarah Lamb in Don Quixote, ©ROH/Johan Persson, 2013 Carlos Acosta’s vibrant dance production of Miguel de Cervante’s classic tale Don Quixote returns to the Royal Opera House this Spring. Created specially for The Royal Ballet in 2013, this stunning production tells the story of the bumbling knight Don Quixote and his ever-faithful squire Sancho Panza, and their efforts to help the young lovers Kitri and Basilio. This revival features exciting debuts from Lauren Cuthbertson, Yasmine Naghdi and Mayara Magri as Kitri and Matthew Ball, Alexander Campbell and Marcelino Sambé as Basilio. Don Quixote For all Royal Opera House press releases visit www.roh.org.uk/for/press-and-media includes a number of spectacular solos and pas de deux as well as outlandish comedy and romance as the dashing Basilio steals the heart of the beautiful Kitri. Don Quixote will be live streamed to cinemas on Tuesday 19 February as part of the ROH Live Cinema Season. Carlos Acosta previously danced the role of Basilio in many productions of Don Quixote. He was invited by Kevin O’Hare Director of The Royal Ballet, to re-stage this much-loved classic in 2013. Acosta’s vibrant production evokes sunny Spain with designs by Tim Hatley who has also created productions for the National Theatre and for musicals including Dreamgirls, The Bodyguard and Shrek. Acosta’s choreography draws on Marius Petipa’s 1869 production of this classic ballet and is set to an exuberant score by Ludwig Minkus arranged and orchestrated by Martin Yates. -

Is There a Hidden Jewish Meaning in Don Quixote?

From: Cervantes: Bulletin of the Cervantes Society of America , 24.1 (2004): 173-88. Copyright © 2004, The Cervantes Society of America. Is There a Hidden Jewish Meaning in Don Quixote? MICHAEL MCGAHA t will probably never be possible to prove that Cervantes was a cristiano nuevo, but the circumstantial evidence seems compelling. The Instrucción written by Fernán Díaz de Toledo in the mid-fifteenth century lists the Cervantes family as among the many noble clans in Spain that were of converso origin (Roth 95). The involvement of Miguel’s an- cestors in the cloth business, and his own father Rodrigo’s profes- sion of barber-surgeon—both businesses that in Spain were al- most exclusively in the hand of Jews and conversos—are highly suggestive; his grandfather’s itinerant career as licenciado is so as well (Eisenberg and Sliwa). As Américo Castro often pointed out, if Cervantes were not a cristiano nuevo, it is hard to explain the marginalization he suffered throughout his life (34). He was not rewarded for his courageous service to the Spanish crown as a soldier or for his exemplary behavior during his captivity in Al- giers. Two applications for jobs in the New World—in 1582 and in 1590—were denied. Even his patron the Count of Lemos turn- 173 174 MICHAEL MCGAHA Cervantes ed down his request for a secretarial appointment in the Viceroy- alty of Naples.1 For me, however, the most convincing evidence of Cervantes’ converso background is the attitudes he displays in his work. I find it unbelievable that anyone other than a cristiano nuevo could have written the “Entremés del retablo de las maravi- llas,” for example. -

Cervantes and the Spanish Baroque Aesthetics in the Novels of Graham Greene

TESIS DOCTORAL Título Cervantes and the spanish baroque aesthetics in the novels of Graham Greene Autor/es Ismael Ibáñez Rosales Director/es Carlos Villar Flor Facultad Facultad de Letras y de la Educación Titulación Departamento Filologías Modernas Curso Académico Cervantes and the spanish baroque aesthetics in the novels of Graham Greene, tesis doctoral de Ismael Ibáñez Rosales, dirigida por Carlos Villar Flor (publicada por la Universidad de La Rioja), se difunde bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-SinObraDerivada 3.0 Unported. Permisos que vayan más allá de lo cubierto por esta licencia pueden solicitarse a los titulares del copyright. © El autor © Universidad de La Rioja, Servicio de Publicaciones, 2016 publicaciones.unirioja.es E-mail: [email protected] CERVANTES AND THE SPANISH BAROQUE AESTHETICS IN THE NOVELS OF GRAHAM GREENE By Ismael Ibáñez Rosales Supervised by Carlos Villar Flor Ph.D A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy At University of La Rioja, Spain. 2015 Ibáñez-Rosales 2 Ibáñez-Rosales CONTENTS Abbreviations ………………………………………………………………………….......5 INTRODUCTION ...…………………………………………………………...….7 METHODOLOGY AND STRUCTURE………………………………….……..12 STATE OF THE ART ..……….………………………………………………...31 PART I: SPAIN, CATHOLICISM AND THE ORIGIN OF THE MODERN (CATHOLIC) NOVEL………………………………………38 I.1 A CATHOLIC NOVEL?......................................................................39 I.2 ENGLISH CATHOLICISM………………………………………….58 I.3 THE ORIGIN OF THE MODERN -

Texto Completo

Don Quijote en el jazz italiano HANS CHRISTIAN HAGEDORN Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha Resumen La recepción de la obra maestra de Cervantes en la música italiana es un tema al que se han dedicado numerosos trabajos de investigación. Sin embargo, los estudios existentes se han centrado sobre todo en la ópera; escasa atención se ha prestado hasta ahora a otros géneros musicales. En este artículo nos ocupamos de las huellas que la novela cervantina ha dejado en el jazz italiano, concretamente en las últimas dos décadas, puesto que en Italia casi todos los ejemplos pertenecen al siglo XXI. El objetivo de nuestro estudio consiste en documentar, analizar y comparar varios ejemplos representativos de composiciones del jazz italiano que están inspiradas en esta obra cumbre de la literatura del Siglo de Oro español. Palabras clave: Don Quijote, música, jazz italiano, recepción Abstract The reception of Cervantes’ masterpiece in Italian music has been explored in a great number of works of research. However, articles on this subject matter have focused mainly on opera; other musical genres have, so far, received little attention. The present paper deals with the traces that the Cervantine novel has left in Italian jazz, in particular in the past two decades, since almost all examples of these jazz musicalizations of Don Quixote within Italy are found in the 21st century. The goal of our study is to document, analyse and compare several representative examples of Italian jazz compositions inspired by this masterwork of the Golden Age of Spanish literature. Key words: Don Quixote, music, Italian jazz, reception, influence 1. -

Exhibition Booklet, Printing Cervantes

This man you see here, with aquiline face, chestnut hair, smooth, unwrinkled brow, joyful eyes and curved though well-proportioned nose; silvery beard which not twenty years ago was golden, large moustache, small mouth, teeth neither small nor large, since he has only six, and those are in poor condition and worse alignment; of middling height, neither tall nor short, fresh-faced, rather fair than dark; somewhat stooping and none too light on his feet; this, I say, is the likeness of the author of La Galatea and Don Quijote de la Mancha, and of him who wrote the Viaje del Parnaso, after the one by Cesare Caporali di Perusa, and other stray works that may have wandered off without their owner’s name. This man you see here, with aquiline face, chestnut hair, smooth, unwrinkled brow, joyful eyes and curved though well-proportioned nose; silvery beard which not twenty years ago was golden, large moustache, small mouth, teeth neither small nor large, since he has only six, and those are in poor condition and worse alignment; of middling height, neither tall nor short, fresh-faced, rather fair than dark; somewhat stooping and none too light on his feet; this, I say, is the likeness of the author of La Galatea and Don Quijote de la Mancha, and of him who wrote the Viaje del Parnaso, after the one by Cesare Caporali di Perusa, and other stray works that may have wandered off without their owner’s name. This man you see here, with aquiline Printingface, chestnut hair, smooth,A LegacyCervantes: unwrinkled of Words brow, and Imagesjoyful eyes and curved though well-proportioned nose; Acknowledgements & Sponsors: With special thanks to the following contributors: Drs. -

National Plan for Abbeys, Monasteries and Convents

NATIONAL PLAN FOR ABBEYS, MONASTERIES AND CONVENTS NATIONAL PLAN FOR ABBEYS, MONASTERIES AND CONVENTS INDEX Page INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 3 OBJECTIVES AND METHOD FOR THE PLAN’S REVISION .............................................. 4 1. BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................... 6 1.1.- Inception of the Plan ............................................................................................. 6 1.2.- Groundwork.......................................................................................................... 6 1.3.- Initial objectives .................................................................................................... 7 1.4.- Actions undertaken by the IPCE after signing the Agreement .............................. 8 1.5.- The initial Plan’s background document (2003). ................................................... 9 2. METHODOLOGICAL ASPECTS .............................................................................. 13 2.1.- Analysis of the initial Plan for Abbeys, Monasteries and Convents ..................... 13 2.2.- Intervention criteria ............................................................................................. 14 2.3.- Method of action ................................................................................................. 17 2.4.- Coordination of actions ...................................................................................... -

The Universal Quixote: Appropriations of a Literary Icon

THE UNIVERSAL QUIXOTE: APPROPRIATIONS OF A LITERARY ICON A Dissertation by MARK DAVID MCGRAW Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Eduardo Urbina Committee Members, Paul Christensen Juan Carlos Galdo Janet McCann Stephen Miller Head of Department, Steven Oberhelman August 2013 Major Subject: Hispanic Studies Copyright 2013 Mark David McGraw ABSTRACT First functioning as image based text and then as a widely illustrated book, the impact of the literary figure Don Quixote outgrew his textual limits to gain near- universal recognition as a cultural icon. Compared to the relatively small number of readers who have actually read both extensive volumes of Cervantes´ novel, an overwhelming percentage of people worldwide can identify an image of Don Quixote, especially if he is paired with his squire, Sancho Panza, and know something about the basic premise of the story. The problem that drives this paper is to determine how this Spanish 17th century literary character was able to gain near-univeral iconic recognizability. The methods used to research this phenomenon were to examine the character´s literary beginnings and iconization through translation and adaptation, film, textual and popular iconography, as well commercial, nationalist, revolutionary and institutional appropriations and determine what factors made him so useful for appropriation. The research concludes that the literary figure of Don Quixote has proven to be exceptionally receptive to readers´ appropriative requirements due to his paradoxical nature. The Quixote’s “cuerdo loco” or “wise fool” inherits paradoxy from Erasmus of Rotterdam’s In Praise of Folly. -

Fiction Excerpt 2: from the Adventures of Don Quixote

Fiction Excerpt 2: From The Adventures of Don Quixote (retold with excerpts from the novel by Miguel de Cervantes) Once upon a time, in a village in La Mancha, there lived a lean, thin-faced old gentleman whose favorite pastime was to read books about knights in armor. He loved to read about their daring exploits, strange adventures, bold rescues of damsels in distress, and intense devotion to their ladies. In fact, he became so caught up in the subject of chivalry that he neglected every other interest and even sold many acres of good farmland so that he might buy all the books he could get on the subject. He would lie awake at night, absorbed in every detail of these fantastic adventures. He would often engage in arguments with the village priest or the barber over who was the greatest knight of all time. Was it Amadis of Gaul or Palmerin of England? Or was it perhaps the Knight of the Sun? As time went on, the old gentleman crammed his head so full of these stories and lost so much sleep from reading through the night that he lost his wits completely. He began to believe that all the fantastic and romantic tales he read about enchantments, challenges, battles, wounds, and wooings were true histories. At last he fell into the strangest fancy that any madman has ever had: he resolved to become himself a knight errant, to travel through the world with horse and armor in search of adventures. First he got out some rust-eaten armor that had belonged to his ancestors, then cleaned and repaired it as best he could. -

Maquetación 1

TOLEDO CASTILLA LAMAN CHA x THERE’S SO MUCH TO SEE AND FEEL! Toledo and its province are a complete and particular showcase for your senses. The ca - pital, one of the most attractive old towns in the world, is the hub of an environment rich in artistic and cultural heritage. Its villas and wetlands from La Mancha are a haven of peace where you can enjoy the Cervan - tine atmosphere. Its hills, mountains, fo - rests, ‘rañas’, rivers and meadows are part of a natural environment of singular beauty. Its festivities, traditions and gastronomy are an invitation to live the unequalled attractive of the lands of Toledo. ENDLESS TOLEDO… AND CAPITAL OF GASTRONOMY By the end of the 11 th Century the poet Yehuda ha Levi wrote: ‘The city where I live is big, and its inhabitants are giants’. He was ac - tually talking about Toledo, the place where Jewish, Muslims and Christians gave an example of cohabitation and tolerance. Located on the top of a hill, protected by the Tagus River, Toledo still preserves that open-minded character. All civilizations that have been in the Iberian Peninsula have made of this setting an im - portant one, enriching it with their culture and arts. Each genera - tion gave it a bit more beauty. UNESCO understood it so in 1986 by declaring it a World Heritage Site. Writer Julio Caro Baroja said that Toledo is a luxury that Spain has. A luxury at your fingertips. Being home to more than a hundred monuments, its streets invite you to enjoy the joys of its Roman, Visigothic, Jewish, Muslim and Christian past. -

Cervantes the Cervantes Society of America Volume Xxvi Spring, 2006

Bulletin ofCervantes the Cervantes Society of America volume xxvi Spring, 2006 “El traducir de una lengua en otra… es como quien mira los tapices flamencos por el revés.” Don Quijote II, 62 Translation Number Bulletin of the CervantesCervantes Society of America The Cervantes Society of America President Frederick De Armas (2007-2010) Vice-President Howard Mancing (2007-2010) Secretary-Treasurer Theresa Sears (2007-2010) Executive Council Bruce Burningham (2007-2008) Charles Ganelin (Midwest) Steve Hutchinson (2007-2008) William Childers (Northeast) Rogelio Miñana (2007-2008) Adrienne Martin (Pacific Coast) Carolyn Nadeau (2007-2008) Ignacio López Alemany (Southeast) Barbara Simerka (2007-2008) Christopher Wiemer (Southwest) Cervantes: Bulletin of the Cervantes Society of America Editors: Daniel Eisenberg Tom Lathrop Managing Editor: Fred Jehle (2007-2010) Book Review Editor: William H. Clamurro (2007-2010) Editorial Board John J. Allen † Carroll B. Johnson Antonio Bernat Francisco Márquez Villanueva Patrizia Campana Francisco Rico Jean Canavaggio George Shipley Jaime Fernández Eduardo Urbina Edward H. Friedman Alison P. Weber Aurelio González Diana de Armas Wilson Cervantes, official organ of the Cervantes Society of America, publishes scholarly articles in Eng- lish and Spanish on Cervantes’ life and works, reviews, and notes of interest to Cervantistas. Tw i ce yearly. Subscription to Cervantes is a part of membership in the Cervantes Society of America, which also publishes a newsletter: $20.00 a year for individuals, $40.00 for institutions, $30.00 for couples, and $10.00 for students. Membership is open to all persons interested in Cervantes. For membership and subscription, send check in us dollars to Theresa Sears, 6410 Muirfield Dr., Greensboro, NC 27410.