The Universal Quixote: Appropriations of a Literary Icon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Don Quixote and Legacy of a Caricaturist/Artistic Discourse

Don Quixote and the Legacy of a Caricaturist I Artistic Discourse Rupendra Guha Majumdar University of Delhi In Miguel de Cervantes' last book, The Tria/s Of Persiles and Sigismunda, a Byzantine romance published posthumously a year after his death in 1616 but declared as being dedicated to the Count of Lemos in the second part of Don Quixote, a basic aesthetie principIe conjoining literature and art was underscored: "Fiction, poetry and painting, in their fundamental conceptions, are in such accord, are so close to each other, that to write a tale is to create pietoríal work, and to paint a pieture is likewise to create poetic work." 1 In focusing on a primal harmony within man's complex potential of literary and artistic expression in tandem, Cervantes was projecting a philosophy that relied less on esoteric, classical ideas of excellence and truth, and more on down-to-earth, unpredictable, starkly naturalistic and incongruous elements of life. "But fiction does not", he said, "maintain an even pace, painting does not confine itself to sublime subjects, nor does poetry devote itself to none but epie themes; for the baseness of lífe has its part in fiction, grass and weeds come into pietures, and poetry sometimes concems itself with humble things.,,2 1 Quoted in Hans Rosenkranz, El Greco and Cervantes (London: Peter Davies, 1932), p.179 2 Ibid.pp.179-180 Run'endra Guha It is, perhaps, not difficult to read in these lines Cervantes' intuitive vindication of the essence of Don Quixote and of it's potential to generate a plural discourse of literature and art in the years to come, at multiple levels of authenticity. -

Literature and Cartography in Early Modern Spain: Etymologies and Conjectures Simone Pinet

18 • Literature and Cartography in Early Modern Spain: Etymologies and Conjectures Simone Pinet By the time Don Quijote began to tilt at windmills, maps footprints they leave on the surface of the earth they and mapping had made great advances in most areas— touch, they become one with the maps of their voyages. administrative, logistic, diplomatic— of the Iberian To his housekeeper Don Quijote retorts, world.1 Lines of inquiry about literature and cartography Not all knights can be courtiers, nor can or should all in early modern Spanish literature converge toward courtiers be knights errant: of all there must be in the Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quijote. The return to the world, and even if all of us are knights, there is a vast heroic age of the chivalric romance, with its mysterious difference between them, because the courtiers, with- geography, contrasted with Don Quijote’s meanderings out leaving their chambers or the thresholds of the around the Iberian peninsula, is especially ironic in view court, walk the whole world looking at a map, with- of what the author, a wounded veteran of military cam- out spending a penny, or suffering heat or cold, hunger paigns (including Lepanto, a battle seen in many maps or thirst; but we, the true knights errant, exposed to the and naval views, and his captivity in Algiers, with com- sun, the cold, the air, the merciless weather night and parable cartographic resonance), probably knew about day, on foot and on horseback, we measure the whole cartography. earth with our own feet, and we do not know the ene- 2 A determining proof of the relation and a fitting epi- mies merely in painting, but in their very being. -

Las Transformaciones De Aldonza Lorenzo

Lemir 14 (2010): 205-215 ISSN: 1579-735X ISSN: Las transformaciones de Aldonza Lorenzo Mario M. González Universidade de São Paulo RESUMEN: Aldonza Lorenzo aparece en el Quijote tan solo como la base real en que se apoya la creación de la dama del caballero andante, Dulcinea del Toboso, a partir del pasado enamoramiento del hidalgo por la labradora. No obstante, permanece en la novela como una referencia tanto para don Quijote como para su escudero. Para el caballero, lo que permite esa aproximación es la hermosura y la honestidad de una y otra, exacta- mente los atributos que Sancho Panza niega radicalmente en Aldonza para crear lo que puede llamarse una «antidulcinea». A la obsesión de don Quijote por desencantar a Dulcinea, parecería subyacer la de salvar la hermosura y honestidad de Aldonza Lorenzo. De hecho, cuando todos los elementos de la realidad son paulatinamente recuperados por el caballero en su vuelta a la cordura, la única excepción es Aldonza Lo- renzo, de quien Alonso Quijano sugestivamente nada dice antes de morir. ABSTRACT: Aldonza Lorenzo appears in Cervantes’s Don Quixote merely as the source that gave birth to the knight- errant’s imagined ladylove Dulcinea del Toboso ever since the Hidalgo fell in love with the farm girl in the past. However, Aldonza Lorenzo remains a reference to Don Quixote and his squire Sancho Panza throughout the novel. For the knight, beauty and honesty aproximate both girls, the real and the imagi- nary, while his squire denies those virtues in Aldonza creating what can be defined as an «anti-dulcinea». -

Goya, Autor De Dos Imágenes De Don Quijote

cervantistas 1 4/8/01 19:33 Página 415 GOYA, AUTOR DE DOS IMÁGENES DE DON QUIJOTE Isabel Escandell Proust En la exposición de 1905 de la Biblioteca Nacional1, para conmemorar el tercer centenario de la publicación del Quijote, se reunió un importante número de obras de arte con imágenes relativas a la novela, entre ellas dos estampas de Goya, identificadas como La Aventura del rebuzno y La Visión de don Quijote2. En el catálogo de la exposición se indicaba de la primera que, partiendo de un dibujo de este pintor, se había realizado un grabado para la edición de la Academia de 1780 que al final no se incluyó. Aún son dos imágenes poco conocidas, de importancia menor entre otras obras de Goya, y envueltas de cierto misterio. Este estudio aborda las dos imágenes en su contexto histórico- artístico, e intenta deshacer la visión romántica en torno al pintor y a sus obras. A MODO DE INTRODUCCIÓN Afinales del siglo XVIII e inicios del XIX los españoles conocían a Goya como pintor religioso, retratista, diseñador de cartones para tapices, como autor de sus aguafuertes Caprichos (1799) y Tauromaquia (1816) o de las estampas sobre cuadros de Velázquez, que se anunciaron en la prensa madrileña. Es probable que solo sus amigos íntimos conocieran su obra pictórica más ima- ginativa, sus dibujos satíricos sobre temas religiosos o políticos o las series de grabados Desastres de la Guerra y Disparates, ediciones póstumas de 1863 y 1864.3 Ahora, sus dibujos y estampas se custodian en importantes museos, y a pesar de la extensa bibliografía sobre Francisco de Goya todavía quedan temas por estudiar. -

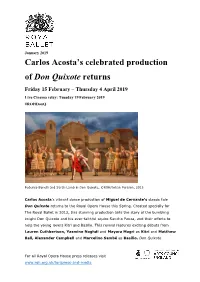

Don Quixote Press Release 2019

January 2019 Carlos Acosta’s celebrated production of Don Quixote returns Friday 15 February – Thursday 4 April 2019 Live Cinema relay: Tuesday 19 February 2019 #ROHDonQ Federico Bonelli and Sarah Lamb in Don Quixote, ©ROH/Johan Persson, 2013 Carlos Acosta’s vibrant dance production of Miguel de Cervante’s classic tale Don Quixote returns to the Royal Opera House this Spring. Created specially for The Royal Ballet in 2013, this stunning production tells the story of the bumbling knight Don Quixote and his ever-faithful squire Sancho Panza, and their efforts to help the young lovers Kitri and Basilio. This revival features exciting debuts from Lauren Cuthbertson, Yasmine Naghdi and Mayara Magri as Kitri and Matthew Ball, Alexander Campbell and Marcelino Sambé as Basilio. Don Quixote For all Royal Opera House press releases visit www.roh.org.uk/for/press-and-media includes a number of spectacular solos and pas de deux as well as outlandish comedy and romance as the dashing Basilio steals the heart of the beautiful Kitri. Don Quixote will be live streamed to cinemas on Tuesday 19 February as part of the ROH Live Cinema Season. Carlos Acosta previously danced the role of Basilio in many productions of Don Quixote. He was invited by Kevin O’Hare Director of The Royal Ballet, to re-stage this much-loved classic in 2013. Acosta’s vibrant production evokes sunny Spain with designs by Tim Hatley who has also created productions for the National Theatre and for musicals including Dreamgirls, The Bodyguard and Shrek. Acosta’s choreography draws on Marius Petipa’s 1869 production of this classic ballet and is set to an exuberant score by Ludwig Minkus arranged and orchestrated by Martin Yates. -

Is There a Hidden Jewish Meaning in Don Quixote?

From: Cervantes: Bulletin of the Cervantes Society of America , 24.1 (2004): 173-88. Copyright © 2004, The Cervantes Society of America. Is There a Hidden Jewish Meaning in Don Quixote? MICHAEL MCGAHA t will probably never be possible to prove that Cervantes was a cristiano nuevo, but the circumstantial evidence seems compelling. The Instrucción written by Fernán Díaz de Toledo in the mid-fifteenth century lists the Cervantes family as among the many noble clans in Spain that were of converso origin (Roth 95). The involvement of Miguel’s an- cestors in the cloth business, and his own father Rodrigo’s profes- sion of barber-surgeon—both businesses that in Spain were al- most exclusively in the hand of Jews and conversos—are highly suggestive; his grandfather’s itinerant career as licenciado is so as well (Eisenberg and Sliwa). As Américo Castro often pointed out, if Cervantes were not a cristiano nuevo, it is hard to explain the marginalization he suffered throughout his life (34). He was not rewarded for his courageous service to the Spanish crown as a soldier or for his exemplary behavior during his captivity in Al- giers. Two applications for jobs in the New World—in 1582 and in 1590—were denied. Even his patron the Count of Lemos turn- 173 174 MICHAEL MCGAHA Cervantes ed down his request for a secretarial appointment in the Viceroy- alty of Naples.1 For me, however, the most convincing evidence of Cervantes’ converso background is the attitudes he displays in his work. I find it unbelievable that anyone other than a cristiano nuevo could have written the “Entremés del retablo de las maravi- llas,” for example. -

Cervantes and the Spanish Baroque Aesthetics in the Novels of Graham Greene

TESIS DOCTORAL Título Cervantes and the spanish baroque aesthetics in the novels of Graham Greene Autor/es Ismael Ibáñez Rosales Director/es Carlos Villar Flor Facultad Facultad de Letras y de la Educación Titulación Departamento Filologías Modernas Curso Académico Cervantes and the spanish baroque aesthetics in the novels of Graham Greene, tesis doctoral de Ismael Ibáñez Rosales, dirigida por Carlos Villar Flor (publicada por la Universidad de La Rioja), se difunde bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-SinObraDerivada 3.0 Unported. Permisos que vayan más allá de lo cubierto por esta licencia pueden solicitarse a los titulares del copyright. © El autor © Universidad de La Rioja, Servicio de Publicaciones, 2016 publicaciones.unirioja.es E-mail: [email protected] CERVANTES AND THE SPANISH BAROQUE AESTHETICS IN THE NOVELS OF GRAHAM GREENE By Ismael Ibáñez Rosales Supervised by Carlos Villar Flor Ph.D A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy At University of La Rioja, Spain. 2015 Ibáñez-Rosales 2 Ibáñez-Rosales CONTENTS Abbreviations ………………………………………………………………………….......5 INTRODUCTION ...…………………………………………………………...….7 METHODOLOGY AND STRUCTURE………………………………….……..12 STATE OF THE ART ..……….………………………………………………...31 PART I: SPAIN, CATHOLICISM AND THE ORIGIN OF THE MODERN (CATHOLIC) NOVEL………………………………………38 I.1 A CATHOLIC NOVEL?......................................................................39 I.2 ENGLISH CATHOLICISM………………………………………….58 I.3 THE ORIGIN OF THE MODERN -

He Dreams of Giants

From the makers of Lost In La Mancha comes A Tale of Obsession… He Dreams of Giants A film by Keith Fulton and Lou Pepe RUNNING TIME: 84 minutes United Kingdom, 2019, DCP, 5.1 Dolby Digital Surround, Aspect Ratio16:9 PRESS CONTACT: Cinetic Media Ryan Werner and Charlie Olsky 1 SYNOPSIS “Why does anyone create? It’s hard. Life is hard. Art is hard. Doing anything worthwhile is hard.” – Terry Gilliam From the team behind Lost in La Mancha and The Hamster Factor, HE DREAMS OF GIANTS is the culmination of a trilogy of documentaries that have followed film director Terry Gilliam over a twenty-five-year period. Charting Gilliam’s final, beleaguered quest to adapt Don Quixote, this documentary is a potent study of creative obsession. For over thirty years, Terry Gilliam has dreamed of creating a screen adaptation of Cervantes’ masterpiece. When he first attempted the production in 2000, Gilliam already had the reputation of being a bit of a Quixote himself: a filmmaker whose stories of visionary dreamers raging against gigantic forces mirrored his own artistic battles with the Hollywood machine. The collapse of that infamous and ill-fated production – as documented in Lost in La Mancha – only further cemented Gilliam’s reputation as an idealist chasing an impossible dream. HE DREAMS OF GIANTS picks up Gilliam’s story seventeen years later as he finally mounts the production once again and struggles to finish it. Facing him are a host of new obstacles: budget constraints, a history of compromise and heightened expectations, all compounded by self-doubt, the toll of aging, and the nagging existential question: What is left for an artist when he completes the quest that has defined a large part of his career? 2 Combining immersive verité footage of Gilliam’s production with intimate interviews and archival footage from the director’s entire career, HE DREAMS OF GIANTS is a revealing character study of a late-career artist, and a meditation on the value of creativity in the face of mortality. -

Sobre Crítica Del «Quijote» La Razón Que Nutren La Cultura Y La Reflexión, La Voz De Alonso Quijano

SOBRE CRÍTICA DEL QUIJOTE Maxime Chevalier Hace varias décadas que deja pendientes la crítica cervantina unas preguntas esenciales. Me refiero a la relación entre Cervantes y el protagonista del Qui• jote, por una parte, y, por otra parte, al concepto en que tenía Cervantes los libros y la cultura libresca. Sobre ambas preguntas quisiera explicarme hoy. La primera pregunta la planteó la edad romántica al afirmar que Cervan• tes mal había entendido la grandeza de su héroe. Tal concepto iba ya en germen en la conocida frase de la Estética hegeliana que define el asunto del Quijote como «oposición cómica entre un mundo ordenado según la razón [...] y un alma aislada», frase decisiva por señalar la pauta de la crítica deci• monónica, según la cual la novela cervantina es el conflicto entre prosaísmo y poesía, realidad e ideal, don Quijote y la sociedad. Al tomar este camino, se orientaban forzosamente los estudiosos a quienes competía la definición del protagonista hacia un elogio de la locura, un elogio de la locura radicalmente distinto del de Erasmo, que es elogio jocoso de la simpleza (stultitia).1 E iban a desembocar fatalmente en el dilema enunciado por Marthe Robert: de dos cosas la una, o bien abona el lector el buen sentido cervantino, hipótesis en la que don Quijote no pasa de ser un loco grotesco; o bien vemos en don Quijote una especie de santo escarnecido, y hemos de confesar que Cervantes no en• tendió su propia creación.2 Dilema finamente cincelado —y dilema inacepta• ble. Cualquier lector de buena fe en seguida advierte que dicho dilema no da cuenta de la realidad. -

SPP MAB Active Body Small Planetary Platforms Assessment for Main Asteroid Belt Active Bodies

CDF STUDY REPORT SPP MAB Active Body Small Planetary Platforms Assessment for Main Asteroid Belt Active Bodies CDF-178(B) January 2018 SPP MAB Active Body CDF Study Report: CDF-178(B) January 2018 page 1 of 207 CDF Study Report SPP Main Asteroid Belt Active Body Small Planetary Platforms Assessment For Main Asteroid Belt Active Bodies ESA UNCLASSIFIED – Releasable to the Public SPP MAB Active Body CDF Study Report: CDF-178(B) January 2018 page 2 of 207 FRONT COVER Study Logo showing satellite approaching an asteroid with a swarm of nanosats ESA UNCLASSIFIED – Releasable to the Public SPP MAB Active Body CDF Study Report: CDF-178(B) January 2018 page 3 of 207 STUDY TEAM This study was performed in the ESTEC Concurrent Design Facility (CDF) by the following interdisciplinary team: TEAM LEADER AOCS PAYLOAD COMMUNICATIONS POWER CONFIGURATION PROGRAMMATICS/ AIV COST ELECTRICAL PROPULSION DATA HANDLING CHEMICAL PROPULSION GS&OPS SYSTEMS MISSION ANALYSIS THERMAL MECHANISMS Under the responsibility of: S. Bayon, SCI-FMP, Study Manager With the scientific assistance of: Study Scientist With the technical support of: Systems/APIES Smallsats Radiation The editing and compilation of this report has been provided by: Technical Author ESA UNCLASSIFIED – Releasable to the Public SPP MAB Active Body CDF Study Report: CDF-178(B) January 2018 page 4 of 207 This study is based on the ESA CDF Open Concurrent Design Tool (OCDT), which is a community software tool released under ESA licence. All rights reserved. Further information and/or additional copies of the report can be requested from: S. Bayon ESA/ESTEC/SCI-FMP Postbus 299 2200 AG Noordwijk The Netherlands Tel: +31-(0)71-5655502 Fax: +31-(0)71-5655985 [email protected] For further information on the Concurrent Design Facility please contact: M. -

Institut Für Weltraumforschung (IWF) Österreichische Akademie Der Wissenschaften (ÖAW) Schmiedlstraße 6, 8042 Graz, Austria

WWW.OEAW.AC.AT ANNUAL REPORT 2018 IWF INSTITUT FÜR WELTRAUMFORSCHUNG WWW.IWF.OEAW.AC.AT ANNUAL REPORT 2018 COVER IMAGE Artist's impression of the BepiColombo spacecraft in cruise configuration, with Mercury in the background (© spacecraft: ESA/ATG medialab; Mercury: NASA/JPL). TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 5 NEAR-EARTH SPACE 7 SOLAR SYSTEM 13 SUN & SOLAR WIND 13 MERCURY 15 VENUS 16 MARS 17 JUPITER 18 COMETS & DUST 20 EXOPLANETARY SYSTEMS 21 SATELLITE LASER RANGING 27 INFRASTRUCTURE 29 OUTREACH 31 PUBLICATIONS 35 PERSONNEL 45 IMPRESSUM INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION The Space Research Institute (Institut für Weltraum- ESA's Cluster mission, launched in 2000, still provides forschung, IWF) in Graz focuses on the physics of space unique data to better understand space plasmas. plasmas and (exo-)planets. With about 100 staff members MMS, launched in 2015, uses four identically equipped from 20 nations it is one of the largest institutes of the spacecraft to explore the acceleration processes that Austrian Academy of Sciences (Österreichische Akademie govern the dynamics of the Earth's magnetosphere. der Wissenschaften, ÖAW, Fig. 1). The China Seismo-Electromagnetic Satellite (CSES) was IWF develops and builds space-qualified instruments and launched in February to study the Earth's ionosphere. analyzes and interprets the data returned by them. Its core engineering expertise is in building magnetometers and NASA's InSight (INterior exploration using Seismic on-board computers, as well as in satellite laser ranging, Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport) mission was which is performed at a station operated by IWF at the launched in May to place a geophysical lander on Mars Lustbühel Observatory. -

Guías Diarias Para El Quijote Parte I, Cap

Guías diarias para el Quijote Parte I, cap. 3 RESUMEN: Don Quixote begs the innkeeper, whom he mistakes for the warden of the castle, to make him a knight the next day. Don Quixote says Parte I, cap. 1 that he will watch over his armor until the morning in the chapel, which, RESUMEN: Don Quixote is a fan of “books of chivalry” and spends most he learns, is being restored. A muleteer comes to water his mules and of his time and money on these books. These tales of knight-errantry drive tosses aside the armor and is attacked by Don Quixote. A second muleteer him crazy trying to fathom them and he resolves to resuscitate this does the same thing with the same result. Made nervous by all this, the forgotten ancient order in his modern day in order to help the needy. He innkeeper makes Don Quixote a knight before the morning arrives. cleans his ancestor’s armor, names himself Don Quixote, names his horse, and finds a lady to be in love with. PREGUNTAS: 1. ¿Qué le pide don Quijote al ventero? PREGUNTAS: 2. ¿Por qué quiere hacer esto el ventero? 1. ¿De dónde es don Quijote? 3. ¿Qué aventuras ha tenido el ventero? 2. ¿Era rico don Quijote? 4. ¿Por qué busca don Quijote la capilla? 3. ¿Quiénes vivían con don Quijote? 5. ¿Qué consejos prácticos le da el ventero a don Quijote? 4. ¿Por qué quería tomar la pluma don Quijote? 6. ¿Qué quería hacer el primer arriero al acercarse a don Quijote por la 5.