Teaching the Theories of Evolution and Scientific Creationism in the Public Schools: the First Amendment Religion Clauses and Permissible Relief

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Argumentation and Fallacies in Creationist Writings Against Evolutionary Theory Petteri Nieminen1,2* and Anne-Mari Mustonen1

Nieminen and Mustonen Evolution: Education and Outreach 2014, 7:11 http://www.evolution-outreach.com/content/7/1/11 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Argumentation and fallacies in creationist writings against evolutionary theory Petteri Nieminen1,2* and Anne-Mari Mustonen1 Abstract Background: The creationist–evolutionist conflict is perhaps the most significant example of a debate about a well-supported scientific theory not readily accepted by the public. Methods: We analyzed creationist texts according to type (young earth creationism, old earth creationism or intelligent design) and context (with or without discussion of “scientific” data). Results: The analysis revealed numerous fallacies including the direct ad hominem—portraying evolutionists as racists, unreliable or gullible—and the indirect ad hominem, where evolutionists are accused of breaking the rules of debate that they themselves have dictated. Poisoning the well fallacy stated that evolutionists would not consider supernatural explanations in any situation due to their pre-existing refusal of theism. Appeals to consequences and guilt by association linked evolutionary theory to atrocities, and slippery slopes to abortion, euthanasia and genocide. False dilemmas, hasty generalizations and straw man fallacies were also common. The prevalence of these fallacies was equal in young earth creationism and intelligent design/old earth creationism. The direct and indirect ad hominem were also prevalent in pro-evolutionary texts. Conclusions: While the fallacious arguments are irrelevant when discussing evolutionary theory from the scientific point of view, they can be effective for the reception of creationist claims, especially if the audience has biases. Thus, the recognition of these fallacies and their dismissal as irrelevant should be accompanied by attempts to avoid counter-fallacies and by the recognition of the context, in which the fallacies are presented. -

HUMANISM Religious Practices

HUMANISM Religious Practices . Required Daily Observances . Required Weekly Observances . Required Occasional Observances/Holy Days Religious Items . Personal Religious Items . Congregate Religious Items . Searches Requirements for Membership . Requirements (Includes Rites of Conversion) . Total Membership Medical Prohibitions Dietary Standards Burial Rituals . Death . Autopsies . Mourning Practices Sacred Writings Organizational Structure . Headquarters Location . Contact Office/Person History Theology 1 Religious Practices Required Daily Observance No required daily observances. Required Weekly Observance No required weekly observances, but many Humanists find fulfillment in congregating with other Humanists on a weekly basis (especially those who characterize themselves as Religious Humanists) or other regular basis for social and intellectual engagement, discussions, book talks, lectures, and similar activities. Required Occasional Observances No required occasional observances, but some Humanists (especially those who characterize themselves as Religious Humanists) celebrate life-cycle events with baby naming, coming of age, and marriage ceremonies as well as memorial services. Even though there are no required observances, there are several days throughout the calendar year that many Humanists consider holidays. They include (but are not limited to) the following: February 12. Darwin Day: This marks the birthday of Charles Darwin, whose research and findings in the field of biology, particularly his theory of evolution by natural selection, represent a breakthrough in human knowledge that Humanists celebrate. First Thursday in May. National Day of Reason: This day acknowledges the importance of reason, as opposed to blind faith, as the best method for determining valid conclusions. June 21 - Summer Solstice. This day is also known as World Humanist Day and is a celebration of the longest day of the year. -

Critical Analysis of Article "21 Reasons to Believe the Earth Is Young" by Jeff Miller

1 Critical analysis of article "21 Reasons to Believe the Earth is Young" by Jeff Miller Lorence G. Collins [email protected] Ken Woglemuth [email protected] January 7, 2019 Introduction The article by Dr. Jeff Miller can be accessed at the following link: http://apologeticspress.org/APContent.aspx?category=9&article=5641 and is an article published by Apologetic Press, v. 39, n.1, 2018. The problems start with the Article In Brief in the boxed paragraph, and with the very first sentence. The Bible does not give an age of the Earth of 6,000 to 10,000 years, or even imply − this is added to Scripture by Dr. Miller and other young-Earth creationists. R. C. Sproul was one of evangelicalism's outstanding theologians, and he stated point blank at the Legionier Conference panel discussion that he does not know how old the Earth is, and the Bible does not inform us. When there has been some apparent conflict, either the theologians or the scientists are wrong, because God is the Author of the Bible and His handiwork is in general revelation. In the days of Copernicus and Galileo, the theologians were wrong. Today we do not know of anyone who believes that the Earth is the center of the universe. 2 The last sentence of this "Article In Brief" is boldly false. There is almost no credible evidence from paleontology, geology, astrophysics, or geophysics that refutes deep time. Dr. Miller states: "The age of the Earth, according to naturalists and old- Earth advocates, is 4.5 billion years. -

Intelligent Design Creationism and the Constitution

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Washington University St. Louis: Open Scholarship Washington University Law Review Volume 83 Issue 1 2005 Is It Science Yet?: Intelligent Design Creationism and the Constitution Matthew J. Brauer Princeton University Barbara Forrest Southeastern Louisiana University Steven G. Gey Florida State University Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Education Law Commons, First Amendment Commons, Religion Law Commons, and the Science and Technology Law Commons Recommended Citation Matthew J. Brauer, Barbara Forrest, and Steven G. Gey, Is It Science Yet?: Intelligent Design Creationism and the Constitution, 83 WASH. U. L. Q. 1 (2005). Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview/vol83/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Washington University Law Quarterly VOLUME 83 NUMBER 1 2005 IS IT SCIENCE YET?: INTELLIGENT DESIGN CREATIONISM AND THE CONSTITUTION MATTHEW J. BRAUER BARBARA FORREST STEVEN G. GEY* TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ................................................................................................... 3 INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................. -

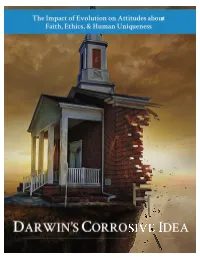

Darwins-Corrosive-Idea.Pdf

This report was prepared and published by Discovery Institute’s Center for Science and Culture, a non-profit, non-partisan educational and research organization. The Center’s mission is to advance the understanding that human beings and nature are the result of intelligent design rather than a blind and undirected process. We seek long-term scientific and cultural change through cutting-edge scientific research and scholarship; education and training of young leaders; communication to the general public; and advocacy of academic freedom and free speech for scientists, teachers, and students. For more information about the Center, visit www.discovery.org/id. FOR FREE RESOURCES ABOUT SCIENCE AND FAITH, VISIT WWW.SCIENCEANDGOD.ORG/RESOURCES. PUBLISHED NOVEMBER, 2016. © 2016 BY DISCOVERY INSTITUTE. DARWIN’S CORROSIVE IDEA The Impact of Evolution on Attitudes about Faith, Ethics, and Human Uniqueness John G. West, PhD* EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In his influential book Darwin’s Dangerous Idea, have asked about the impact of science on a person’s philosopher Daniel Dennett praised Darwinian religious faith typically have not explored the evolution for being a “universal acid” that dissolves impact of specific scientific ideas such as Darwinian traditional religious and moral beliefs.1 Evolution- evolution.5 ary biologist Richard Dawkins has similarly praised In order to gain insights into the impact of Darwin for making “it possible to be an intellect- specific scientific ideas on popular beliefs about ually fulfilled atheist.”2 Although numerous studies God and ethics, Discovery Institute conducted a have documented the influence of Darwinian nationwide survey of a representative sample of theory and other scientific ideas on the views of 3,664 American adults. -

Darwin Day in Deep Time: Promoting Evolutionary Science Through Paleontology Sarah L

Shefeld and Bauer Evo Edu Outreach (2017) 10:10 DOI 10.1186/s12052-017-0073-3 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Darwin Day in deep time: promoting evolutionary science through paleontology Sarah L. Shefeld1,2* and Jennifer E. Bauer2 Abstract Charles Darwin’s birthday, February 12th, is an international celebration coined Darwin Day. During the week of his birthday, universities, museums, and science-oriented organizations worldwide host events that celebrate Darwin’s scientifc achievements in evolutionary biology. The University of Tennessee, Knoxville (UT) has one of the longest running celebrations in the nation, with 2016 marking the 19th year. For 2016, the theme for our weeklong series of events was paleontology, chosen to celebrate new research in the feld and to highlight the specifc misconceptions of evolution within the context of geologic time. We provide insight into the workings of one of our largest and most successful Darwin Day celebration to date, so that other institutions might also be able to host their own rewarding Darwin Day events in the future. Keywords: Charles Darwin, Paleontology, Tennessee, Community, Evolutionary biology, Fossils Introduction event, was given by Dr. Neil Shubin, paleontologist and February 12th is an annual international celebration of author of popular science book Your Inner Fish, was the life and work of Charles Darwin, collectively termed attended by over 600 university and community members. “Darwin Day”. Tese global events have similar objec- Celebrating Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural tives: to educate and excite the public about evolutionary selection is particularly important in the United States, science. Although Darwin’s work is most often discussed where a nearly one-third of the adult population does not in terms of its incredible impact on evolutionary biol- accept the evidence for evolution (Miller et al. -

Beliefs Versus Knowledge: a Necessary Distinction for Explaining, Predicting, and Assessing Conceptual Change

Beliefs Versus Knowledge: A Necessary Distinction for Explaining, Predicting, and Assessing Conceptual Change Thomas D. Griffin ([email protected]) Stellan Ohlsson ([email protected]) Department of Psychology, 1007 West Harrison Street (M/C 285) Chicago, IL 60607, U.S.A. Abstract needed to explain how new knowledge representations can be created that will not be distorted by the Empirical research and theoretical treatments of conflicting prior concepts. They suggest that activation conceptual change have paid little attention to the of conflicting prior concepts activates related abstract distinction between knowledge and belief. The concepts that are not in direct conflict with the new distinction implies that conceptual change involves both knowledge acquisition and belief revision, and highlights information, and that can be utilized in constructing an the need to consider the reasons that beliefs are held. We accurate representation of the new information. These argue that the effects of prior beliefs on conceptual aspects of the conceptual change process become more learning depends upon whether a given belief is held for important when we consider how beliefs differ from its coherence with a network of supporting knowledge, knowledge. or held for the affective goals that it serves. We also contend that the nature of prior beliefs will determine the Belief Versus Knowledge relationship between the knowledge acquisition and the belief revision stages of the conceptual change process. The present paper defines knowledge as the Preliminary data suggests that prior beliefs vary in comprehension or awareness of an idea or proposition whether they are held for knowledge or affect-based ("I understand the claim that humans evolved from reasons, and that this variability may predict whether a early primates"). -

Is Creationism Still Valid in the New Millennium? George T

Perspective Digest Volume 10 Article 5 Issue 3 Summer 2005 Is Creationism Still Valid in the New Millennium? George T. Javor Loma Linda University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/pd Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Javor, George T. (2005) "Is Creationism Still Valid in the New Millennium?," Perspective Digest: Vol. 10 : Iss. 3 , Article 5. Available at: http://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/pd/vol10/iss3/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Perspective Digest by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Javor: Is Creationism Still Valid in the New Millennium? BY GEORGE T. JAVOR* when they show that their explana- The supposed conflict between tions work better than those of evo- religion and science is a recent lutionists. Their goal should be to invention and a distortion of histor- develop their paradigm so well that ical realities by a class of historians people will have to admit, “Nothing whose agenda was to destroy the in biology makes sense except in the influence of religion. The currently light of creationism.” popular secularism in science may IS CREATIONISM STILL With that as a background, con- only be a detour in the history of sci- sider a few aspects of Creationism ence. still valid for 21st century thinking Christians. What are the Perceived Liabilities VALID IN THE of Creationism? Is Creationism a Religiously Creationism originated in a pre- Motivated Paradigm? scientific world, where myths Yes. -

Evolutionism, Creationism, and Treating Religion As a Hobby

Duke Law Journal VOLUME 1987 DECEMBER NUMBER 6 EVOLUTIONISM, CREATIONISM, AND TREATING RELIGION AS A HOBBY STEPHEN L. CARTER* Contemporary liberalism faces no greater dilemma than deciding how to deal with the resurgence of religious belief. On the one hand, liberals cherish religion, as they cherish all matters of private conscience, and liberal theory holds that the state should do nothing to discourage free religious choice. At the same time, contemporary liberals are com- ing to view any religious element in public moral discourse as a tool of the radical right for the reshaping of American society, and that re- shaping is something liberals want very much to discourage. In truth, liberal politics has always been uncomfortable with reli- gious fervor. If liberals cheered the clerics who marched against segrega- tion and the Vietnam War, it was only because the causes were considered just-not because the clerics were devout. Nowadays, people who bring religion into the making of public policy come more fre- quently from the right, and the liberal response all too often is to dismiss them as fanatics. Even the religious left is sometimes offended by the mainstream liberal tendency to mock religious belief. Not long ago, the magazine Sojourners-publishedby politically liberal Christian evangeli- cals-found itself in the unaccustomed position of defending the evangel- * Professor of Law, Yale University. A nearly identical version of this essay was delivered at the Third Annual Duke Law Journal Lecture on February 26, 1987. For publication, I have added a sprinkling of footnotes (most of them citations), clarifed a few points that I learned from the ques- tion-and-answer session had not been put as precisely as they might have, and reintroduced a brief discussion, deleted at the podium, of the work of Mark Yudof and Bruce Ackerman. -

The Darwin Show (Print Version)

LRB · Steven Shapin · The Darwin Show (print version) http://www.lrb.co.uk/v32/n01/steven-shapin/the-darwin-show/print Back to Article page Steven Shapin It has been history’s biggest birthday party. On or around 12 February 2009 alone – the 200th anniversary of Charles Darwin’s birth, ‘Darwin Day’ – there were more than 750 commemorative events in at least 45 countries, and, on or around 24 November, there was another spate of celebrations to mark the 150th anniversary of the publication of On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or, the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life. In Mysore, Darwin Day was observed by an exhibition ‘proclaiming the importance of the day and the greatness of the scientist’. In Charlotte, North Carolina, there were performances of a one-man musical, Charles Darwin: Live & in Concert (‘Twas adaptive radiation that produced the mighty whale;/His hands have grown to flippers/And he has a fishy tail’). At Harvard, the celebrations included ‘free drinks, science-themed rock bands, cake, decor and a dancing gorilla’ (stuffed with a relay of biology students). Circulating around the university, student and faculty volunteers declaimed the entire text of the Origin. On the Galapagos Islands, tourists making scientific haj were treated to ‘an active, life-seeing account of the life of this magnificent scientist’, and a party of Stanford alumni retraced the circumnavigating voyage of HMS Beagle in a well-appointed private Boeing 757, intellectually chaperoned by Darwin’s most distinguished academic biographer. The Darwin anniversaries were celebrated round the world: in Bogotá, Mexico City, Montevideo, Toronto, Toulouse, Frankfurt, Barcelona, Bangalore, Singapore, Seoul, Osaka, Cape Town, Rome (where it was sponsored by the Pontifical Council for Culture, part of a Vatican hatchet-burying initiative), and in all the metropolitan and scientific settings you might expect. -

Young-Earth Creationism, Creation Science, and the Evangelical Denial of Climate Change

religions Article Revisiting the Scopes Trial: Young-Earth Creationism, Creation Science, and the Evangelical Denial of Climate Change K. L. Marshall New College, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh EH1 2LX, UK; [email protected] Abstract: In the century since the Scopes Trial, one of the most influential dogmas to shape American evangelicalism has been that of young-earth creationism. This article explains why, with its arm of “creation science,” young-earth creationism is a significant factor in evangelicals’ widespread denial of anthropogenic climate change. Young-earth creationism has become closely intertwined with doctrines such as the Bible’s divine authority and the Imago Dei, as well as with social issues such as abortion and euthanasia. Addressing this aspect of the environmental crisis among evangelicals will require a re-orientation of biblical authority so as to approach social issues through a hermeneutic that is able to acknowledge the reality and imminent threat of climate change. Citation: Marshall, K. L. 2021. Revisiting the Scopes Trial: Keywords: evangelicalism; creation science; young-earth creationism; climate change; Answers in Young-Earth Creationism, Creation Genesis; biblical literalism; biblical authority; Noahic flood; dispensational theology; fundamentalism Science, and the Evangelical Denial of Climate Change. Religions 12: 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12020133 1. Introduction Academic Editors: Randall Balmer The 1925 Scopes “Monkey” Trial is often referenced as a metonymy for American and Edward Blum Protestantism’s fundamentalist-modernist controversy that erupted in the years following World War I. William Jennings Bryan, the lawyer and politician who argued in favor of Received: 25 January 2021 biblical creationism1—in keeping with his literal understanding of the narratives in Genesis Accepted: 12 February 2021 Published: 20 February 2021 1 and Genesis 2—was vindicated when the judge ruled that high school biology teacher John Scopes had indeed broken the law by teaching Darwinian evolution in a public school. -

Philip M. Gottshall

PHILIP M. NOVACK-GOTTSHALL DEPARTMENT OF BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES BENEDICTINE UNIVERSITY 5700 COLLEGE ROAD LISLE, IL 60532 (630) 829-6514 [email protected] www1.ben.edu/faculty/pnovack-gottshall RESEARCH INTERESTS Comparative paleoecology and ecology of invertebrate animals and marine communities; body size evolution; quantitative methods and null models in ecological diversification and macroevolution; morphometrics, digital imaging, and photomacrography PROFESSIONAL EMPLOYMENT 2009–present Associate Professor, Department of Biological Sciences, Benedictine University, Lisle, IL Tenure awarded September 2013 2005–2009 Assistant Professor, Department of Geosciences, University of West Georgia, Carrollton, GA March 2008: Unanimously promoted at third-year review 2004–2005 Visiting Assistant Professor, Department of Geosciences, University of West Georgia, Carrollton, GA RESEARCH APPOINTMENTS 2009–present Research Associate, Department of Geology, The Field Museum, Chicago, IL 2006–present Participant / Data Contributor, Paleobiology Database (www.paleodb.org) EDUCATION September 2004 Ph.D., Biology, Program in Evolution, Ecology and Organismal Biology, Duke University, Durham, NC Dissertation: Ecology and evolution of deep-subtidal, soft-substrate communities during the Cambrian through Devonian; Advisor: Dr. Daniel W. McShea June 1999 M.S., Geology, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH Thesis: Comparative geographic and environmental diversity dynamics of gastropods and bivalves during the Ordovician Radiation; Advisor: Dr. Arnold I. Miller May 1996 B.S., Summa cum laude with Honors, Moravian College, Bethlehem, PA Double major in Biology and Music Performance (Organ); minor in Chemistry PUBLICATIONS Undergraduate students are in bold 1. Novack-Gottshall, P. and K. Burton. In press (2013/2014). Morphometrics indicates giant Ordovician macluritid gastropods switched life habit during ontogeny. Journal of Paleontology. 2. Payne, J.L., F.A.