Ti Manno: the Haitian Prophet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carnival in the Creole City: Place, Race and Identity in the Age of Globalization Daphne Lamothe Smith College, [email protected]

Masthead Logo Smith ScholarWorks Africana Studies: Faculty Publications Africana Studies Spring 2012 Carnival in the Creole City: Place, Race and Identity in the Age of Globalization Daphne Lamothe Smith College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.smith.edu/afr_facpubs Part of the Africana Studies Commons Recommended Citation Lamothe, Daphne, "Carnival in the Creole City: Place, Race and Identity in the Age of Globalization" (2012). Africana Studies: Faculty Publications, Smith College, Northampton, MA. https://scholarworks.smith.edu/afr_facpubs/4 This Article has been accepted for inclusion in Africana Studies: Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Smith ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected] CARNIVAL IN THE CREOLE CITY: PLACE, RACE, AND IDENTITY IN THE AGE OF GLOBALIZATION Author(s): DAPHNE LAMOTHE Source: Biography, Vol. 35, No. 2, LIFE STORIES FROM THE CREOLE CITY (spring 2012), pp. 360-374 Published by: University of Hawai'i Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23541249 Accessed: 06-03-2019 14:34 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms University of Hawai'i Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Biography This content downloaded from 131.229.64.25 on Wed, 06 Mar 2019 14:34:43 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms CARNIVAL IN THE CREOLE CITY: PLACE, RACE, AND IDENTITY IN THE AGE OF GLOBALIZATION DAPHNE LAMOTHE In both the popular and literary imaginations, carnival music, dance, and culture have come to signify a dynamic multiculturalism in the era of global ization. -

Roczniki Hum$Nistyczne

7RZDU]\VWZR 1DXNRZH .DWROLFNLHJR 8QLZHUV\WHWX /XEHOVNLHJR 7RP;/,9]HV]\W 52&=1,., +80$1,67<&=1( 1(2),/2/2*,$ ALFONS PILORZ EVOLUTION SEMANTIQUE DES EMPRUNTS FRANÇAIS EN POLONAIS /8%/,1 TABLE DES MATIERES Avant-propos ................................. 7 Corpus ..................................... 29 Petitcorpus .................................. 67 Analyse ..................................... 77 Remarquesfinales .............................. 159 Bibliographie ................................. 161 AVANT-PROPOS Si les gens regardaient l’étymologie des mots, peut-être comprendraient-ils que la richesse du français vient du brassage des cultures. («Lire», no 204, p. 43, publicité des diction- naires LE ROBERT) Toute préocupation étymologique suppose une visée diachronique. L’étude de l’emprunt entretient des rapports intimes avec l’analyse étymologique. Cependant elle déborde le cadre strictement linguistique de celle-ci pour entrer de plain-pied dans le domaine de l’histoire des rapports culturels. L’emprunt linguistique est un phénomène panhumain, non moins généralisé que les échanges de biens matériels et de techniques. Depuis de très anciennes époques préhistoriques, les sociétés humaines échangent biens de consommation (sel, par exemple), matières premières (silex, ambre...), instruments (couteaux, grattoirs...). Depuis fort longtemps, il n’y a pratiquement plus de groupements humains autarciques. De même, il n’y a guère d’autarcie sur le plan lingui- stique. Les langues, véhicules de cultures, cultures en permanent brassage (évi- -

Creolizing Contradance in the Caribbean

Peter Manuel 1 / Introduction Contradance and Quadrille Culture in the Caribbean region as linguistically, ethnically, and culturally diverse as the Carib- bean has never lent itself to being epitomized by a single music or dance A genre, be it rumba or reggae. Nevertheless, in the nineteenth century a set of contradance and quadrille variants flourished so extensively throughout the Caribbean Basin that they enjoyed a kind of predominance, as a common cultural medium through which melodies, rhythms, dance figures, and per- formers all circulated, both between islands and between social groups within a given island. Hence, if the latter twentieth century in the region came to be the age of Afro-Caribbean popular music and dance, the nineteenth century can in many respects be characterized as the era of the contradance and qua- drille. Further, the quadrille retains much vigor in the Caribbean, and many aspects of modern Latin popular dance and music can be traced ultimately to the Cuban contradanza and Puerto Rican danza. Caribbean scholars, recognizing the importance of the contradance and quadrille complex, have produced several erudite studies of some of these genres, especially as flourishing in the Spanish Caribbean. However, these have tended to be narrowly focused in scope, and, even taken collectively, they fail to provide the panregional perspective that is so clearly needed even to comprehend a single genre in its broader context. Further, most of these pub- lications are scattered in diverse obscure and ephemeral journals or consist of limited-edition books that are scarcely available in their country of origin, not to mention elsewhere.1 Some of the most outstanding studies of individual genres or regions display what might seem to be a surprising lack of familiar- ity with relevant publications produced elsewhere, due not to any incuriosity on the part of authors but to the poor dissemination of works within (as well as 2 Peter Manuel outside) the Caribbean. -

Michel Martelly

January 2012 NOREF Report President Martelly – call on Haiti's youth! Henriette Lunde Executive summary Half a year has passed since Michel Martelly as a weak state in a land of strong NGOs, the was inaugurated as the new president of Haiti, Haitian state needs to assert itself and take on the and so far the earthquake-devastated country responsibility of providing services to its citizens. has seen little progress from his presidency. The Recruiting young people on a large scale for public reconstruction process is slow, and frustration sector employment in basic service provision and and disgruntlement are growing among the establishing a national youth civic service corps population. Important time was wasted during the would strengthen the position of the state and let five months it took to appoint a new prime minister youth participate in the reconstruction process and put a new government in place. Martelly’s in a meaningful way. However, a civic service mandate was largely given to him by the country’s corps would demand high levels of co-ordination youth, who have high expectations of him. and transparency to avoid becoming an empty Integrating youth into the reconstruction process institution reinforcing patrimonial structures. The is important for reasons of political stability, but youth who brought Martelly to power represent a young people also represent the country’s most great potential asset for the country and need to important resource per se by constituting a large be given the place in the reconstruction process and – relative to their parents – better-educated that they have been promised. -

Rejecting Haitian Refugees Haitian Boatpeople in the Early 1990S

Rejecting Haitian Refugees Haitian Boatpeople in the Early 1990s Sarah L. Joseph Haverford College April 2008 Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………...2 Section One: Haitian History……………………………………………...7 Isolated Black Republic………………………………………………………......8 Racism and Segregation during American Occupation, 1915-1934……………..10 Duvalierism and the First Haitian Boatpeople…………………………………...14 Section Two: Haitian Boatpeople………………………………………...19 Terror after the Coup…………………………………………………………….20 Haitian Boatpeople and US Policy………………………………………………25 Controversy Surrounding US Policy towards Haitian Boatpeople………………29 Politics Surrounding Haitian Boatpeople………………………………………..39 Comparison to Other Refugee Groups…………………………………………...41 Section Three: Haitian Diaspora………………………………………...45 Hardships of the Haitian Diaspora in America…………………………………..46 Fighting for Justice of Haitian Refugees………………………………………...50 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………57 Bibliography………………………………………………………………62 Primary Source Bibliography……………………………………………………63 Secondary Source Bibliography…………………………………………………64 1 Introduction 2 Introduction America, the land of “milk and honey” and “freedom and equality,” has always been a destination for immigrants throughout the world. In fact, a history of the United States is undoubtedly a history of immigration, refuge, and resettlement. The many diverse populations that form the US speaks to the country’s large-scale admittance of immigrants. Groups and individuals migrate to the US in search of better economic opportunities, to -

Haitian Creole – English Dictionary

+ + Haitian Creole – English Dictionary with Basic English – Haitian Creole Appendix Jean Targète and Raphael G. Urciolo + + + + Haitian Creole – English Dictionary with Basic English – Haitian Creole Appendix Jean Targète and Raphael G. Urciolo dp Dunwoody Press Kensington, Maryland, U.S.A. + + + + Haitian Creole – English Dictionary Copyright ©1993 by Jean Targète and Raphael G. Urciolo All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the Authors. All inquiries should be directed to: Dunwoody Press, P.O. Box 400, Kensington, MD, 20895 U.S.A. ISBN: 0-931745-75-6 Library of Congress Catalog Number: 93-71725 Compiled, edited, printed and bound in the United States of America Second Printing + + Introduction A variety of glossaries of Haitian Creole have been published either as appendices to descriptions of Haitian Creole or as booklets. As far as full- fledged Haitian Creole-English dictionaries are concerned, only one has been published and it is now more than ten years old. It is the compilers’ hope that this new dictionary will go a long way toward filling the vacuum existing in modern Creole lexicography. Innovations The following new features have been incorporated in this Haitian Creole- English dictionary. 1. The definite article that usually accompanies a noun is indicated. We urge the user to take note of the definite article singular ( a, la, an or lan ) which is shown for each noun. Lan has one variant: nan. -

CARIBBEAN AMERICAN HERITAGE MONTH Caribbean History and Culture

U . S . D E P A R T M E N T O F T H E I N T E R I O R CARIBBEAN AMERICAN HERITAGE MONTH Caribbean History and Culture WHY CARIBBEAN AMERICAN HERITAGE MONTH? Caribbean American Heritage Month was established to create and disseminate knowledge about the contributions of Caribbean people to the United States. H I S T O R Y O F C A R I B B E A N A M E R I C A N H E R I T A G E M O N T H In the 19th century, the U.S. attracted many Caribbean's who excelled in various professions such as craftsmen, scholars, teachers, preachers, doctors, inventors, comedians, politicians, poets, songwriters, and activists. Some of the most notable Caribbean Americans are Alexander Hamilton, first Secretary of the Treasury, Colin Powell, the first person of color appointed as the Secretary of the State, James Weldon Johnson, the writer of the Black National Anthem, Celia Cruz, the world-renowned "Queen of Salsa" music, and Shirley Chisholm, the first African American Congresswoman and first African American woman candidate for President, are among many. PROCLAMATION TIMELINE 2004 2005 2006 Ms. Claire A. Nelson, The House passed the A Proclamation Ph.D. launched the Bill for recognizing the making the Resolution official campaign for significance of official was signed by June as National Caribbean Americans the President in June Caribbean American in 2005. 2006. Heritage Month in 2004. D E M O G R A P H Y Caribbean Population in the United States Countries 1980-2017 Ninety percent of Caribbean 5,000,000 people came from five countries: Cuba, Dominican Republic, Jamaica, Haiti, 4,000,000 Trinidad, and Tobago. -

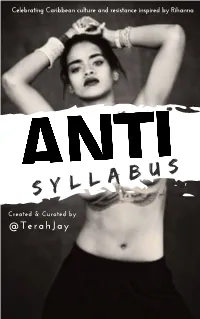

Anti Syllabus

Celebrating Caribbean culture and resistance inspired by Rihanna A B U S S Y L L Created & Curated by @TerahJay ⠠⠗⠊⠓⠁ ⠝⠝⠁⠂ ⠞⠓⠁⠝⠅ ⠽⠕⠥ ⠋⠕⠗ ⠑⠧⠑⠗⠽ ⠞⠓⠊⠝⠛ ⠲ ⠠⠇⠕⠧⠑ y a J h a r e T - . s a y ⠽⠕⠥ w l a u o y e v o L . g n ⠁⠇⠺⠁⠽ i h t y r e v e r o f u o y k ⠎⠂ n a h t a n n a h i R ⠠⠞⠑⠗⠁ ⠓⠠⠚⠁⠽ ⠲ MUST BE LOVE ON THE BRAIN That resistance to conformity, that resistance to needing and pleasing and placating the global marketplace is absolutely very much situated within her context. Anti is actively telling you, song after song, that it's not trying to fit Heather D. Russell On January 28th 2017 Rihanna celebrated her one-year anniversarih, aptly titled ANTiversary. Her highly anticipated 8th studio album was a work of art that upon its release, shifted the course of her craft and career. The eclectic, raw, emotional, album was molecule shifting for Rihanna as well as her fanbase the Rihanna Navy. Rihanna states: "I had no idea how it would be recieved, neither was that something I considered. I just wanted to make a body of work that felt right." In many ways ANTi was not about finding herself as an artist, it was more about creating and re-creating herself as a complete person. Someone unafraid, someone boundless. In her process she trusted the way the music made her feel. As a Black woman from Barbados it is important to situate her life, career, and way of knowing within a specific Caribbean context. -

Playbill Covers Feb Mar 2015-2016 FINAL.Indd 5 2/4/16 10:30 AM © 2009 the Coca-Cola Company

2015 – 2016 SEASON PL AY BILL FEB. 27 –MAR. 22 FAC Playbill Covers_Feb_Mar_2015-2016_FINAL.indd 5 2/4/16 10:30 AM © 2009 The Coca-Cola Company. ĽCokeľ and the Contour Bottle are trademarks of The Coca-Cola Company. 2 Arts UMass of supporter is Coca-Cola Bravo! a the proud Center. Fine A Notable Lifestyle Celebrating lifelong enjoyment of the arts Discover gracious, refined independent living in a social and dynamic environment. Meet passionate, enlightened residents–from academics to artists–that will inspire you. The Loomis Communities offer an unparalleled lifestyle with superior amenities and services—with the added peace of mind for the future that comes from access to LiveWell@Loomis. APPLEWOOD LOOMIS VILLAGE Amherst, MA South Hadley, MA 413-253-9833 413-532-5325 The Western Massachusetts www.loomiscommunities.org Pioneer in Senior Living UMASS Performing Arts Ad.indd 1 6/13/2013 2:36:54 PM 3 5 MESSAGE FROM OUR DIRECTOR We’re so glad you could join us this spring, as we’re rounding out our 40th anniversary season! We have a great lineup of shows still to come – there truly is something for everyone. Whether it’s classical, jazz, world music, dance or STOMP, we have some real crowd-pleasers planned for the remaining months of our anniversary season. Spring is really a time for new beginnings, and we know that many of our patrons are taking stock of what’s important to them. If you’re looking to start something new this season, don’t forget to include the Arts! At the FAC, we take our role very seriously, since we provide a way for our audience members to connect – not only with the artists and performers they see here, but with each other as well. -

Of International Publications in Aerospace Medicine

DOT/FAA/AM-07/2 Office of Aerospace Medicine Washington, DC 20591 Index of International Publications in Aerospace Medicine Melchor J. Antuñano Katherine Wade Civil Aerospace Medical Institute Federal Aviation Administration Oklahoma City, OK 73125 January 2007 Final Report NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for the contents thereof. ___________ This publication and all Office of Aerospace Medicine technical reports are available in full-text from the Civil Aerospace Medical Institute’s publications Web site: www.faa.gov/library/reports/medical/oamtechreports/index.cfm Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. DOT/FAA/AM-07/2 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Index of International Publications in Aerospace Medicine January 2007 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Antuñano MJ, Wade K 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) FAA Civil Aerospace Medical Institute P.O. Box 25082 Oklahoma City, OK 73125 11. Contract or Grant No. 12. Sponsoring Agency name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Office of Aerospace Medicine Federal Aviation Administration 800 Independence Ave., S.W. Washington, DC 20591 14. Sponsoring Agency Code 15. Supplemental Notes 16. Abstract The 3rd edition of the Index of International Publications in Aerospace Medicine is a comprehensive listing of international publications in clinical aerospace medicine, operational aerospace medicine, aerospace physiology, environmental medicine/physiology, diving medicine/physiology, aerospace human factors, as well as other topics directly or indirectly related to aerospace medicine. -

Interview Elizabeth Mcalister

Search PROGRAMS BLOG HIP DEEP DONATE ABOUT The tragedy of the earthquake in Haiti continues to unfold with reports of over 100,000 deaths, some one million homeless and now countless orphans being stolen or abused. We continue to ask everyone in the Afropop community to contribute as generously as possible to relief organizations on the ground now. We have prepared a list for you. Singer-songwriter and vodou priest Erol Josue offers us a song from his “Requiem for Haiti” 21 song cycle. In “Manyan Voude” Erol says “We have to accept the decision of the Almighty. Even though the loss is big we have to rebuild.” It’s powerful. Also on our blog is international superstar Wyclef Jean, performing a song featuring rara carnival music at the recent Hope-For-Haiti-Now telethon. Please go to our blog and add your comments. The below interview was done for the Afropop Worldwide Hip Deep program, "Music and the Story of Haiti," recently re-released and streaming here. (Just click the hi or lo stream link below the image on the page.) In 2007, Afropop’s Sean Barlow visited Elizabeth McAlister—Liza to her friends-- at her home in Middletown Connecticut where she is a Professor in the Religion Department at Wesleyan University. Liza has focused her research and writing work on Haiti. She authored the acclaimed book, “Rara!: Vodou, Power and Performance in Haiti and its Diaspora” and has compiled two beautiful albums based on her field recordings—“Angels in the Mirror—Vodou Music of Haiti” (Ellipsis Arts) and “Rhythms of Rapture: The Sacred Musics of Haitian Vodou”(Smithsonian Folkways). -

Haitians: a People on the Move. Haitian Cultural Heritage Resource Guide

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 416 263 UD 032 123 AUTHOR Bernard, Marie Jose; Damas, Christine; Dejoie, Menes; Duval, Joubert; Duval, Micheline; Fouche, Marie; Marcellus, Marie Jose; Paul, Cauvin TITLE Haitians: A People on the Move. Haitian Cultural Heritage Resource Guide. INSTITUTION New York City Board of Education, Brooklyn, NY. Office of Bilingual Education. ISBN ISBN-1-55839-416-8 PUB DATE 1996-00-00 NOTE 176p. AVAILABLE FROM Office of Instructional Publications, 131 Livingston Street, Brooklyn, NY 11201. PUB TYPE Books (010) Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC08 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Cultural Awareness; Cultural Background; Diversity (Student); Ethnic Groups; Foreign Countries; Haitian Creole; *Haitians; History; *Immigrants; Inservice Teacher Education; *Multicultural Education; Resource Materials; Teaching Guides; Teaching Methods; Urban Schools; *Urban Youth IDENTIFIERS Haiti; New York City Board of Education ABSTRACT This cultural heritage resource guide has been prepared as a tool for teachers to help them understand the cultural heritage of their Haitian students, their families, and their communities in order to serve them better. Although Haiti became an independent country in 1804, the struggle of its people for justice and freedom has never ended. Many Haitians have left Haiti for political, social, and economic reasons, and many have come to the larger cities of the United States, particularly New York City. This guide contains the following sections: (1) "Introduction"; (2) "Haiti at a Glance"; (3) "In Search of a Better Life";(4) "Haitian History"; (5) "Haitian Culture"; (6) "Images of Haiti"; and (7)"Bibliography," a 23-item list of works for further reading. (SLD) ******************************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document.