Life After Zouk: Emerging Popular Music of the French Antilles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

El Rey Vallenato De La Academia Camilo Andrés Molina Luna Pontificia

EL REY VALLENATO DE LA ACADEMIA CAMILO ANDRÉS MOLINA LUNA PONTIFICIA UNIVERSIDAD JAVERIANA FACULTAD DE ARTES TESIS DE PREGRADO BOGOTÁ D.C 2017 1 Tabla de contenido 1.Introducción ........................................................................................................ 3 2.Objetivos ............................................................................................................. 3 2.1.Objetivos generales ............................................................................................... 3 2.2.Objetivos específicos ............................................................................................ 3 3.Justificación ....................................................................................................... 4 4.Marco teórico ...................................................................................................... 4 5.Metodología y análisis ..................................................................................... 22 6.Conclusiones .................................................................................................... 32 2 1. Introducción A lo largo de mi carrera como músico estuve influenciado por ritmos populares de Colombia. Específicamente por el vallenato del cual aprendí y adquirí experiencia desde niño en los festivales vallenatos; eventos en los cuales se trata de rescatar la verdadera esencia de este género conformado por caja, guacharaca y acordeón. Siempre relacioné el vallenato con todas mis actividades musicales. La academia me dio -

Liste CD Vinyle Promo Rap Hip Hop RNB Reggae DJ 90S 2000… HIP HOP MUSIC MUSEUM CONTACTEZ MOI [email protected] LOT POSSIBLE / NEGOCIABLE 2 ACHETES = 1 OFFERT

1 Liste CD Vinyle Promo Rap Hip Hop RNB Reggae DJ 90S 2000… HIP HOP MUSIC MUSEUM CONTACTEZ MOI [email protected] LOT POSSIBLE / NEGOCIABLE 2 ACHETES = 1 OFFERT Type Prix Nom de l’artiste Nom de l’album de Genre Année Etat Qté média 2Bal 2Neg 3X plus efficacae CD Rap Fr 1996 2 6,80 2pac How do u want it CD Single Hip Hop 1996 1 5,50 2pac Until the end of time CD Single Hip Hop 2001 1 1,30 2pac Until the end of time CD Hip Hop 2001 1 5,99 2 Pac Part 1 THUG CD Digi Hip Hop 2007 1 12 3 eme type Ovnipresent CD Rap Fr 1999 1 20 11’30 contre les lois CD Maxi Rap Fr 1997 1 2,99 racists 44 coups La compil 100% rap nantais CD Rap Fr 1 15 45 Scientific CD Rap Fr 2001 1 14 50 Cent Get Rich or Die Trying CD Hip Hop 2003 1 2,90 50 CENT The new breed CD DVD Hip Hop 2003 1 6 50 Cent The Massacre CD Hip Hop 2005 2 1,90 50 Cent The Massacre CD dvd Hip Hop 2005 1 7,99 50 Cent Curtis CD Hip Hop 2007 1 3,50 50 Cent After Curtis CD Diggi Hip Hop 2007 1 5 50 Cent Self District CD Hip Hop 2009 1 3,50 100% Ragga Dj Ewone CD 2005 1 5 Reggaetton 113 Prince de la ville CD Rap Fr 2000 2 4,99 113 Jackpotes 2000 CD Single Rap Fr 2000 1 3,80 2 113 Tonton du bled CD Rap Fr 2000 1 0,99 113 Dans l’urgence CD Rap Fr 2003 1 3,90 113 Degrès CD Rap Fr 2005 1 4,99 113 Un jour de paix CD Rap Fr 2006 1 2,99 113 Illegal Radio CD Rap Fr 2006 1 3,49 113 Universel CD Rap Fr 2010 1 5,99 1995 La suite CD Rap Fr 1995 1 9,40 Aaliyah One In A Million CD Hip Hop 1996 1 9 Aaliyah I refuse & more than a CD single RNB 2001 1 8 woman Aaliyah feat Timbaland We need a resolution CD Single -

A Framework for the Static and Dynamic Analysis of Interaction Graphs

A Framework for the Static and Dynamic Analysis of Interaction Graphs DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sitaram Asur, B.E., M.Sc. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Prof. Srinivasan Parthasarathy, Adviser Prof. Gagan Agrawal Adviser Prof. P. Sadayappan Graduate Program in Computer Science and Engineering c Copyright by Sitaram Asur 2009 ABSTRACT Data originating from many different real-world domains can be represented mean- ingfully as interaction networks. Examples abound, ranging from gene expression networks to social networks, and from the World Wide Web to protein-protein inter- action networks. The study of these complex networks can result in the discovery of meaningful patterns and can potentially afford insight into the structure, properties and behavior of these networks. Hence, there is a need to design suitable algorithms to extract or infer meaningful information from these networks. However, the challenges involved are daunting. First, most of these real-world networks have specific topological constraints that make the task of extracting useful patterns using traditional data mining techniques difficult. Additionally, these networks can be noisy (containing unreliable interac- tions), which makes the process of knowledge discovery difficult. Second, these net- works are usually dynamic in nature. Identifying the portions of the network that are changing, characterizing and modeling the evolution, and inferring or predict- ing future trends are critical challenges that need to be addressed in the context of understanding the evolutionary behavior of such networks. To address these challenges, we propose a framework of algorithms designed to detect, analyze and reason about the structure, behavior and evolution of real-world interaction networks. -

Carnival in the Creole City: Place, Race and Identity in the Age of Globalization Daphne Lamothe Smith College, [email protected]

Masthead Logo Smith ScholarWorks Africana Studies: Faculty Publications Africana Studies Spring 2012 Carnival in the Creole City: Place, Race and Identity in the Age of Globalization Daphne Lamothe Smith College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.smith.edu/afr_facpubs Part of the Africana Studies Commons Recommended Citation Lamothe, Daphne, "Carnival in the Creole City: Place, Race and Identity in the Age of Globalization" (2012). Africana Studies: Faculty Publications, Smith College, Northampton, MA. https://scholarworks.smith.edu/afr_facpubs/4 This Article has been accepted for inclusion in Africana Studies: Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Smith ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected] CARNIVAL IN THE CREOLE CITY: PLACE, RACE, AND IDENTITY IN THE AGE OF GLOBALIZATION Author(s): DAPHNE LAMOTHE Source: Biography, Vol. 35, No. 2, LIFE STORIES FROM THE CREOLE CITY (spring 2012), pp. 360-374 Published by: University of Hawai'i Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23541249 Accessed: 06-03-2019 14:34 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms University of Hawai'i Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Biography This content downloaded from 131.229.64.25 on Wed, 06 Mar 2019 14:34:43 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms CARNIVAL IN THE CREOLE CITY: PLACE, RACE, AND IDENTITY IN THE AGE OF GLOBALIZATION DAPHNE LAMOTHE In both the popular and literary imaginations, carnival music, dance, and culture have come to signify a dynamic multiculturalism in the era of global ization. -

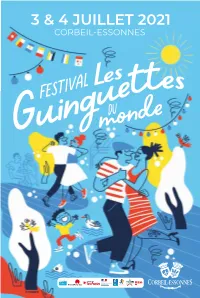

3 & 4 Juillet 2021

3 & 4 JUILLET 2021 CORBEIL-ESSONNES À L’ENTRÉE DU SITE, UNE FÊTE POPULAIRE POUR D’UNE RIVE À L’AUTRE… RE-ENCHANTER NOTRE TERRITOIRE Pourquoi des « guinguettes » ? à établir une relation de dignité Le 3 juillet Le 4 juillet Parce que Corbeil-Essonnes est une avec les personnes auxquelles nous 12h 11h30 ville de tradition populaire qui veut nous adressons. Rappelons ce que le rester. Parce que les guinguettes le mot culture signifie : « les codes, Parade le long Association des étaient des lieux de loisirs ouvriers les normes et les valeurs, les langues, des guinguettes originaires du Portugal situés en bord de rivière et que nous les arts et traditions par lesquels une avons cette chance incroyable d’être personne ou un groupe exprime SAMBATUC Bombos portugais son humanité et les significations Départ du marché, une ville traversée par la Seine et Batucada Bresilienne l’Essonne. qu’il donne à son existence et à son place du Comte Haymont développement ». Le travail culturel 15h Pourquoi « du Monde » ? vers l’entrée du site consiste d’abord à vouloir « faire Parce qu’à Corbeil-Essonnes, 93 Super Raï Band humanité ensemble ». le monde s’est donné rendez-vous, Maghreb brass band 12h & 13h30 108 nationalités s’y côtoient. Notre République se veut fraternelle. 16h15 Aquarela Nous pensons que cela est On ne peut concevoir une humanité une chance. fraternelle sans des personnes libres, Association des Batucada dignes et reconnues comme telles Alors pourquoi une fête des originaires du Portugal dans leur identité culturelle. 15h « guinguettes du monde » Bombos portugais Association Scène à Corbeil-Essonnes ? À travers cette manifestation, 18h Parce que c’est tellement bon de c’est le combat éthique de Et Sonne faire la fête. -

Liste CD / Vinyle Collection En Vente Reggae Ragga Dancehall… 2 Achetés = 1 Offert Lot Possible Et Négociable Contactez Hip Hop Music Museum

1 Liste CD / Vinyle Collection en vente Reggae Ragga dancehall… 2 achetés = 1 offert Lot possible et négociable Contactez hip hop music museum Type Prix Nom de l’artiste Nom de l’album de Genre Année Etat Qté média 100% Ragga Dj Ewone CD 2005 1 5 Reggaetton Admiral T Touchez l’horizon Vinyl Dancehall 2006 1 9,50 Admiral T Instinct admiral CD Dancehall 2010 1 6,99 Digipack Alpha Blondy Revolution CD Reggae 1987 0 2,90 Alpha Blondy Masada CD Reggae 1992 1 25 Alpha Blondy Yitzhak rabin CD Reggae 2010 1 25 Alpha Blondy Vision CD Reggae 2011 1 6,99 And why not Move your skin CD Reggae 1990 1 3,99 Anthony B Universal struggle CD Reggae 1997 1 6,99 ASWAD Not Satisfied CD Reggae 1994 0 9,90 Baaba maal Yela CD Single Reggae 1993 1 29,99 promo Bad manners Inner London violence CD Reggae 1994 1 20,99 Baobab Reggae social club CD Reggae 2001 1 9,99 Beyond the front line Various CD Reggae 1990 1 2,55 Big Red RED emption /respect or die CD Single Reggae 1999 1 6,99 Big Red Big Redemption CD Ragga 1999 3 1,98 2 Big RED REDsistance CD Reggae 2001 1 2,40 Black Uhuru RED CD Reggae 1981 1 1,80 Bob Marley Natty Dread Vinyl Reggae 1974 0 18 Bob Marley Survival CD Reggae 1979 1 10 Bob Marley Saga CD Reggae 1990 1 4,40 Bob Marley Iron lion zion Reggae 1992 1 1,99 Bob Marley Dont rock my boat CD Reggae 1993 1 4,50 Bob Marley Talkin blues CD Reggae 1995 1 10 BoB Marley Keep on moving CD Reggae 1996 1 6 Bob Marley Bob MARLEY CD Reggae 1997 1 8,20 Bob Marley Chant down Babylon CD Reggae 1999 1 3 Bob Marley One love best of CD Reggae 2001 1 10 Bob Marley Thank you -

Shilliam, Robbie. "Dread Love: Reggae, Rastafari, Redemption." the Black Pacific: Anti- Colonial Struggles and Oceanic Connections

Shilliam, Robbie. "Dread Love: Reggae, RasTafari, Redemption." The Black Pacific: Anti- Colonial Struggles and Oceanic Connections. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015. 109–130. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 23 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474218788.ch-006>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 23 September 2021, 11:28 UTC. Copyright © Robbie Shilliam 2015. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 6 Dread Love: Reggae, RasTafari, Redemption Introduction Over the last 40 years roots reggae music has been the key medium for the dissemination of the RasTafari message from Jamaica to the world. Aotearoa NZ is no exception to this trend wherein the direct action message that Bob Marley preached to ‘get up stand up’ supported the radical engagements in the public sphere prompted by Black Power.1 In many ways, Marley’s message and demeanour vindicated the radical oppositional strategies that activists had deployed against the Babylon system in contradistinction to the Te Aute Old Boy tradition of tactful engagement. No surprise, then, that roots reggae was sometimes met with consternation by elders, although much of the issue revolved specifically around the smoking of Marijuana, the wisdom weed.2 Yet some activists and gang members paid closer attention to the trans- mission, through the music, of a faith cultivated in the Caribbean, which professed Ethiopia as the root and Haile Selassie I as the agent of redemption. And they decided to make it their faith too. -

Grime + Gentrification

GRIME + GENTRIFICATION In London the streets have a voice, multiple actually, afro beats, drill, Lily Allen, the sounds of the city are just as diverse but unapologetically London as the people who live here, but my sound runs at 140 bpm. When I close my eyes and imagine London I see tower blocks, the concrete isn’t harsh, it’s warm from the sun bouncing off it, almost comforting, council estates are a community, I hear grime, it’s not the prettiest of sounds but when you’ve been raised on it, it’s home. “Grime is not garage Grime is not jungle Grime is not hip-hop and Grime is not ragga. Grime is a mix between all of these with strong, hard hitting lyrics. It's the inner city music scene of London. And is also a lot to do with representing the place you live or have grown up in.” - Olly Thakes, Urban Dictionary Or at least that’s what Urban Dictionary user Olly Thake had to say on the matter back in 2006, and honestly, I couldn’t have put it better myself. Although I personally trust a geezer off of Urban Dictionary more than an out of touch journalist or Good Morning Britain to define what grime is, I understand that Urban Dictionary may not be the most reliable source due to its liberal attitude to users uploading their own definitions with very little screening and that Mr Thake’s definition may also leave you with more questions than answers about what grime actually is and how it came to be. -

(English-Kreyol Dictionary). Educa Vision Inc., 7130

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 401 713 FL 023 664 AUTHOR Vilsaint, Fequiere TITLE Diksyone Angle Kreyol (English-Kreyol Dictionary). PUB DATE 91 NOTE 294p. AVAILABLE FROM Educa Vision Inc., 7130 Cove Place, Temple Terrace, FL 33617. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Vocabularies /Classifications /Dictionaries (134) LANGUAGE English; Haitian Creole EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC12 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Alphabets; Comparative Analysis; English; *Haitian Creole; *Phoneme Grapheme Correspondence; *Pronunciation; Uncommonly Taught Languages; *Vocabulary IDENTIFIERS *Bilingual Dictionaries ABSTRACT The English-to-Haitian Creole (HC) dictionary defines about 10,000 English words in common usage, and was intended to help improve communication between HC native speakers and the English-speaking community. An introduction, in both English and HC, details the origins and sources for the dictionary. Two additional preliminary sections provide information on HC phonetics and the alphabet and notes on pronunciation. The dictionary entries are arranged alphabetically. (MSE) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. *********************************************************************** DIKSIONt 7f-ngigxrzyd Vilsaint tick VISION U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Office of Educational Research and Improvement EDU ATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION "PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THIS CENTER (ERIC) MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTED BY This document has been reproduced as received from the person or organization originating it. \hkavt Minor changes have been made to improve reproduction quality. BEST COPY AVAILABLE Points of view or opinions stated in this document do not necessarily represent TO THE EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES official OERI position or policy. INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC)." 2 DIKSYCAlik 74)25fg _wczyd Vilsaint EDW. 'VDRON Diksyone Angle-Kreyal F. Vilsaint 1992 2 Copyright e 1991 by Fequiere Vilsaint All rights reserved. -

The Trumpet As a Voice of Americana in the Americanist Music of Gershwin, Copland, and Bernstein

THE TRUMPET AS A VOICE OF AMERICANA IN THE AMERICANIST MUSIC OF GERSHWIN, COPLAND, AND BERNSTEIN DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Amanda Kriska Bekeny, M.M. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Timothy Leasure, Adviser Professor Charles Waddell _________________________ Dr. Margarita Ophee-Mazo Adviser School of Music ABSTRACT The turn of the century in American music was marked by a surge of composers writing music depicting an “American” character, via illustration of American scenes and reflections on Americans’ activities. In an effort to set American music apart from the mature and established European styles, American composers of the twentieth century wrote distinctive music reflecting the unique culture of their country. In particular, the trumpet is a prominent voice in this music. The purpose of this study is to identify the significance of the trumpet in the music of three renowned twentieth-century American composers. This document examines the “compositional” and “conceptual” Americanisms present in the music of George Gershwin, Aaron Copland, and Leonard Bernstein, focusing on the use of the trumpet as a voice depicting the compositional Americanisms of each composer. The versatility of its timbre allows the trumpet to stand out in a variety of contexts: it is heroic during lyrical, expressive passages; brilliant during festive, celebratory sections; and rhythmic during percussive statements. In addition, it is a lead jazz voice in much of this music. As a dominant voice in a variety of instances, the trumpet expresses the American character of each composer’s music. -

A Portrayal of Gender and a Description of Gender Roles in Selected American Modern and Postmodern Plays

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2002 A Portrayal of Gender and a Description of Gender Roles in Selected American Modern and Postmodern Plays. Bonny Ball Copenhaver East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Copenhaver, Bonny Ball, "A Portrayal of Gender and a Description of Gender Roles in Selected American Modern and Postmodern Plays." (2002). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 632. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/632 This Dissertation - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Portrayal of Gender and a Description of Gender Roles in Selected American Modern and Postmodern Plays A dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Analysis East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Education in Educational Leadership and Policy Analysis by Bonny Ball Copenhaver May 2002 Dr. W. Hal Knight, Chair Dr. Jack Branscomb Dr. Nancy Dishner Dr. Russell West Keywords: Gender Roles, Feminism, Modernism, Postmodernism, American Theatre, Robbins, Glaspell, O'Neill, Miller, Williams, Hansbury, Kennedy, Wasserstein, Shange, Wilson, Mamet, Vogel ABSTRACT The Portrayal of Gender and a Description of Gender Roles in Selected American Modern and Postmodern Plays by Bonny Ball Copenhaver The purpose of this study was to describe how gender was portrayed and to determine how gender roles were depicted and defined in a selection of Modern and Postmodern American plays. -

Is This Jazz?: Newport Jazz Fest '18 Review,EDM Event Preview: Tight Crew's Block Rockin Beats,Getting Down and Dirty At

Jazz Insights: Bonnie Mann Three years ago we lost one of jazz’s popular cabaret singers. Eighty-five year old Bonnie Mann (Boncorsi Wotherspoon) was born in Pawtucket. Known for her big- band style singing she regularly could be found throughout Rhode Island with many of the great performing jazz and dance groups. Bonnie sang at the old King & Queens’ Restaurant on Mineral Spring Avenue with, at the time, the young Mike Renzi and others. Her beauty, style and professional voice continually captured local audiences. Her renditions of early American Song Book compositions became favorites among her loyal following. She was a constant worker for the Providence Musician’s Union and was known by musicians state-wide. Her friends numbered in the hundreds. In her later years she performed quite regularly with the late Mac Chrupcala and his several jazz groups. Bonnie kept singing with her heart to her very end; she died in January 2015. The jazz industry in Rhode Island will not forget the late Bonnie Mann.and her dynamic jazz singing voice. Ball Drop Beat Drop: More fun than should be allowed Much like the extra dry champagne served on the holiday, New Year’s Eve traditions can be a bit stale. Interested in switching it up? Then head to Platforms Dance Club in Providence on December 31 to ring in the new year at Tight Crew (TC)’s Neon Masquerade Ball! You may want to buy your tickets now, because this limited-ticket event will feature 16 DJs from all over the US, fire performances, a heated outdoor tent and a game room! So pick out a cute outfit and get plenty of rest, because the event runs from 6pm to 3am.