Master´S Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 44 10. April 1959: Fraktionssitzung

SPD – 03. WP Fraktionssitzung: 10. April. 1959 44 10. April 1959: Fraktionssitzung AdsD, SPD-BT-Fraktion 3. WP 88.1 Überschrift: »Kurzprotokoll der Fraktionssitzung der SPD am Donnerstag, den 10. 4. 1959«. Tagesordnung: Reiseberichte 1. Besuch der Genossen Erler, Paul, Mattick und Metzger in Belgrad und Prag; Be- richterstatter: Erler und Paul 2. Reise der Genossen Deist und Kurlbaum nach Südostasien; Berichterstatter: Heinrich Deist 3. Reise der Genossen Blachstein, Birkelbach, Bleiß und Ludwig nach Algerien; Be- richterstatter: Paul Bleiß 4. Reise des Genossen Harri Bading nach dem Irak; Berichterstatter: Harri Bading Vorsitz: Fritz Erler, anschließend Heinrich Deist Fritz Erler berichtet über die Reise nach Jugoslawien.2 Gespräche wurden geführt mit Kardelj, Vlachovicz, Popovicz, Bebler und Tito.3 Zum Thema Berlin vertraten die Gesprächspartner die Auffassung, daß eine Lösung in größeren Zusammenhängen (europäische Sicherheit, Disengagement) vorzuziehen sei, notfalls müsse aber eine isolierte Lösung, evtl. unter Einschaltung der UNO, ins Auge gefaßt werden. Eine andere Nuancierung war bei Tito selbst festzustellen, der eine isolierte Lösung weder für nützlich noch möglich hielt: sie würde nur Anlaß zu neuen Konflikten sein. Ein Disengagement wurde lebhaft begrüßt. Gesprochen wurde auch über eine evtl. Beteiligung Jugoslawiens an den Mächteverhandlungen, da es mindestens genauso be- troffen sei wie Polen und die ČSSR. Das Thema atomwaffenfreie Zone wurde von den Gesprächspartnern nicht von selbst aufgeworfen, man zeigte sich aber dieser Frage gegenüber sehr aufgeschlossen. Erler verglich im Gespräch in diesem Zusammenhang das Bedroht-Fühlen Jugoslawiens durch Albanien mit dem Bedroht-Fühlen Ulbrichts durch Westberlin. Tito warf u. a. bei Erörterung des Deutschlandplans die Frage auf, warum von uns freie Wahlen erst in der dritten Etappe verlangt würden. -

60 Jahre Wehrbeauftragter Des Deutschen Bundestages 1959-2019

60 Jahre Wehrbeauftragter des Deutschen Bundestages 1959 – 2019 Expertensymposium vom 20. bis 22. Mai 2019 im Schloss & Gut Liebenberg 60 Jahre Wehrbeauftragter des Deutschen Bundestages 1959 – 2019 Expertensymposium vom 20. bis 22. Mai 2019 im Schloss & Gut Liebenberg 4 Vorwort 8 Das Amt des Wehrbeauftragten – eine demokratische Errungenschaft Rede von Bundestagspräsident Dr. Wolfgang Schäuble 20 Aller Anfang ist schwer – Kandidatensuche und Überwindung von Widerständen Oberstleutnant Dr. Rudolf J. Schlaffer Zentrum für Militärgeschichte und Sozialwissen- schaften der Bundeswehr 46 Innere Führung – bloß eine intellektuelle Spielerei? Prof. Dr. Loretana de Libero Führungsakademie der Bundeswehr 62 Innere Führung – wie geht es weiter? Generalmajor Reinhardt Zudrop Zentrum Innere Führung 68 Eingabe beim Wehrbeauftragten, Beschwerde nach der Wehrbeschwerdeordnung oder Gespräch mit dem Militärseelsorger? Inhalt 2 74 Militärisches Ombudswesen – eine internationale Perspektive 78 Die Beziehung zwischen Wehrbeauftragtem, Deutschem Bundestag und Bundeswehr 82 Armee zwischen Grundbetrieb, Bündnis- verteidigung und Einsatz. Geänderte Rahmen- bedingungen für die parlamentarische Kontrolle Generalleutnant Jörg Vollmer Inspekteur des Heeres Roderich Kiesewetter Mitglied des Deutschen Bundestages 86 Zum Tagungsort Schloss & Gut Liebenberg Prof. Dr. Michael Epkenhans, Zentrum für Militärgeschichte und Sozialwissenschaften der Bundeswehr 96 Teilnehmerinnen und Teilnehmer 3 Wann die Geschichte beginnt, ist nicht ganz eindeutig zu datieren. 1956 trat mit den neuen Wehrartikeln die einschlägige Grundgesetzänderung in Kraft, Art. 45b: „Zum Schutz der Grundrechte und als Hilfsorgan des Bundestages für die Ausübung der parlamentarischen Kontrolle wird ein Wehrbeauftragter des Bundestages berufen. Das Nähere regelt ein Bun- desgesetz.“ Dieses Gesetz kam 1957. Es bestimmt unter anderem, dass der Wehrbeauftragte auch über die Ein- haltung der Grundsätze der Inneren Führung wachen soll. Hier ist der neue Begriff „Innere Führung“ zum ersten Mal gesetzlich verankert. -

BWBS/Heft 7/Inhalt

Bundeskanzler-Willy-Brandt-Stiftung Schriftenreihe Heft 7 PerspektivenPerspektiven aus den Exiljahren BUNDESKANZLER-WILLY-BRANDT-STIFTUNG HERAUSGEBER Bundeskanzler-Willy-Brandt-Stiftung Der Vorstand Präsident a. D. Dr. Gerhard Groß (Vorsitzender) Prof. Dr. Dieter Dowe Prof. Dr. Gregor Schöllgen REDAKTION Dr. Wolfram Hoppenstedt, Dr. Bernd Rother, Carsten Tessmer © 2000 by Bundeskanzler-Willy-Brandt-Stiftung im Rathaus Schöneberg John-F.-Kennedy-Platz D-10825 Berlin Telefon 030/78 77 07-0 Telefax 030/78 77 07-50 E-Mail: [email protected] Internet: http://www.willy-brandt.org GESTALTUNG Löning Werbeagentur, Berlin REALISATION UND DRUCK Wenng Druck Gmbh, Dinkelsbüh Alle Rechte vorbehalten Printed in Germany 2000 ISSN 1434-6176 ISBN 3-933090-06-7 Einhart Lorenz (Hrsg.) P erspektiven aus den Exiljahren W issenschaftlicher Workshop in Zusammenarbeit mit dem Nordeuropa-Institut der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin am 9. Februar 2000 Schriftenreihe der Bundeskanzler-Willy-Brandt-Stiftung Heft 7 í INHALT W illy Brandt – Stationen seines Lebens Seite 7 Gerhard Gross Grusswort des Vorstandsvorsitzenden der Bundeskanzler-Willy-Brandt-Stiftung Seite 9 Einhart Lorenz Einführung Seite 13 Knut Kjeldstadli Die Norwegische Arbeiterbewegung in Willy Brandts Seite 19 norwegischen Jahren Einhart Lorenz Der junge Willy Brandt, die Judenverfolgung und die Frage einer jüdischen Heimstätte in Palästina Seite 33 Klaus Misgeld Willy Brandt und Schweden – Schweden und Willy Brandt Seite 49 4 Helga Grebing Entscheidung für die SPD – und was dann? Bemerkungen zu den politischen Aktivitäten der Linkssozialisten aus der SAP in den ersten Jahren „nach Hitler“ Seite 71 P eter Brandt Willy Brandt und die Jugendradikalisierung der späten sechziger Jahre – Anmerkungen eines Historikers und Zeitzeugen Seite 79 5 BPK „Ich scheue mich nicht, hier noch einmal zu sagen: Die Jahre in Norwegen und im übrigen Norden haben für mich viel bedeutet. -

Wilhelm Wanka Collection – Printed Books

Wilhelm Wanka Collection – Printed Books (Special Collections Room, University of Winnipeg Library, Centennial Hall, 515 Portage Avenue, Winnipeg, Manitoba) Catalogued in 1996 Contents 1. By Author 2. By Title 3. By Subject 1. By author Author Title Imprint Subject Call number 100 Jahre Auswärtiges Amt 1870 -1970 / Bonn : Auswärtiges Amt, 1970. Germany. Auswärtiges Amt -- DD 221 E5 herausgegeben vom Auswärtigen Amt. History.;Germany -- Foreign relations -- 1970 1971- 40 Jahre Bundesrepublik Deutschland : Köln : Verlag Wissenschaft und Germany (West) -- Politics and JN 3971 Verantwortung für Deutschland / herausgegeben Politik, c1989. government.;Germany -- Politics and A2A15 von Dieter Blumenwitz und Gottfried Zieger. government -- 1945-1990. 1989 40 Jahre nach Flucht und Vertreibung -- : als der Düsseldorf : Rau, 1 985. World War, 1939 -1945 -- D 809 Exodus begann : Augenzeugen berichten / Hans- Refugees;Refugees -- Germany G3A15 Ulrich Engel (Hg.). (West);Refugees -- Europe, 1985 Eastern.;Germans -- Europe, Eastern;Europe, Eastern -- Ethnic relations. 50 Jahre Münchner Abkommen : Zusammenhä nge München : Institutum Bohemicum, Germans -- Czechoslovakia -- Politics DB 2042 Erkenntnisse Urteile Perspektiven. 1988. and government.;Sudetenland (Czech G4F9 Republic) -- Politics and government. 1988 Aber das Herz Hä ngt daran : ein Gemeinschaftswerk Stuttgart : Brentanoverlag, c1955. German literature -- Czechoslovakia -- PT 3838 der Heimatvertriebenan. Sudetenland.;Sudetenland (Czech S94A2 Republic) -- Literary collections. 1955 Arbeiterbewegung -

SPD – 04. WP Fraktionssitzung: 05.03.1963

SPD – 04. WP Fraktionssitzung: 05. 03. 1963 49 5. März 1963: Fraktionssitzung AdsD, SPD-BT-Fraktion 4. WP, Ord. 8. 1. 63 – 23. 4. 63 (alt 1033, neu 9). Überschrift: »Protokoll der Fraktionssitzung am Dienstag, d. 5. 3. 1963, 15.00 Uhr«. Anwesend: 163 Abgeordnete. Prot.: Scheele. Zeit: 15.15 – 18.15 Uhr. Zu Beginn der Sitzung begrüßte Erich Ollenhauer den anstelle des verstorbenen Ge- nossen Altmaier in den Bundestag nachgerückten Genossen Gerhard Flämig.1 Danach beglückwünschte er die Berliner Abgeordneten zu ihrem großartigen Wahl- erfolg2 und kündigte für die nächste in Berlin stattfindende Fraktionssitzung eine Stel- lungnahme Willy Brandts dazu an.3 Die Tagesordnung wurde angenommen. Zu 1) Politischer Bericht. Zunächst berichtet Herbert Wehner über die unter dem Vorsitz von Erich Ollenhauer stattgefundene Zusammenkunft der Parteivorsitzenden der Sozialistischen Internatio- nale am 23. und 24. 2. in Brüssel.4 Thema dieser Konferenz war der Beitritt Großbri- tanniens zur EWG bzw. die Situation nach dem Scheitern der Beitrittsverhandlungen. Auf dieser Konferenz berichtete der belgische Außenminister5 einführend über die Beitrittsverhandlungen Englands zur EWG und schilderte die Lage nach dem Scheitern dieser Verhandlungen sehr pessimistisch.6 Der österreichische Außenminister Kreisky7 erläuterte den Standpunkt der EFTA-Länder, wobei er besonders darauf hinwies, daß durch das Bestehen zweier Wirtschaftsgruppen in Europa ein Wirtschaftskrieg zwi- schen diesen beiden Gruppen unbedingt vermieden werden müsse. Dänemarks Au- ßenminister Haekkerup8 erläuterte den Standpunkt der skandinavischen Länder und hob besonders hervor, daß auch de Gaulle einsehen müsse, daß Europa nicht ohne die USA zu verteidigen sei. Der außenpolitische Sprecher der Labour-Party Walker9 be- zeichnete das Scheitern der Verhandlungen nicht als ein Verhängnis. -

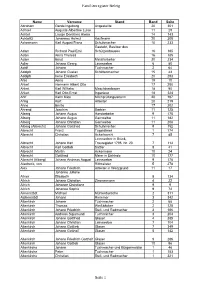

Familienregister Bd Nummer Sortiert

Familienregister Belzig Name Vorname Stand Band Seite Abraham Gerda Ingeborg Angestellte 20 301 Achsel Auguste Albertine Luise 11 29 Achtel Louise Dorothea Alwine 14 143 Achtelitz Johannes Helmut Kaufmann 20 308 Ackermann Karl August Franz Schuhmacher 10 233 Gastwirt, Besitzer des Adam Richard Paul Emil Schützenhauses 16 185 Adam Anna Theresa 16 185 Adam Ernst Metallarbeiter 20 234 Adler Johann Georg Leineweber 680 Adolf Johann Tuchmacher 2 64 Adolph Johann Gustav Schlittenmacher 15 43 Adolph Irene Elisabeth 20 293 Ahle Anna 19 10 Ahlert Hermann Albert Otto 17 280 Ahlert Karl Wilhelm Maschinenbauer 18 90 Ahlert Karl Otto Ernst Ingenieur 18 324 Ahlf Karin Käte Milchprüfungsleiterin 20 187 Ahlig Kurt Arbeiter 20 219 Ahne Emilie 17 202 Ahrend Joachim Barbier 11 125 Alberg Johann August Handarbeiter 9 178 Alberg Johann August Garnweber 11 182 Alberg Johann Christian Garnweber 11 208 Alberg (Albrecht) Johann Gottfried Schuhmacher 9 152 Albrecht Franz Tagelöhner 1 174 Albrecht Christian Ackerknecht 785 Leineweber in Brück, Albrecht Johann Karl Trauregister 1795 Nr. 20 7 113 Albrecht Karl Gottlob Sattler 8 41 Albrecht Martin Ackermann 10 24 Albrecht Gottfried Meier in Eichholz 10 177 Albrecht (Alberg) Johann Andreas August Leineweber 9 178 Alenbeck, von Rittmeister 5 278 Alex Johann Friedrich Arbeiter in Weitzgrund 11 17 Johanne Juliane Allner Elisabeth 8 134 Allrich Johann Christian Zimmermann 4 22 Allrich Johanne Christiane 99 Allrich Johanne Sophia 972 Almenstädt Michael Mühlenbursche 2 311 Alphenstädt Johann Riemmer 3 342 Altenkirch Johann -

Sozialdemokratie Und Kirchen in Deutschland – Ein Historischer Rückblick

Rainer Hering Sozialdemokratie und Kirchen in Deutschland – ein historischer Rückblick Das Verhältnis von Sozialdemokratie und Arbeiterbewegung zu den christlichen Kirchen war lange Zeit sehr anspannt. Dies wirkte sich bis weit in die zweite Hälfte des 20. Jahrhunderts aus. Erst nach der Verabschiedung des Godesberger Programms 1959, in dem explizit der öffentlich-rechtliche Schutz für Religionsgemeinschaften sowie die erklärte Bereitschaft zur Zusammenarbeit mit den Kirchen „im Sinne einer freien Partnerschaft“ formuliert worden war, erfolgte eine Annäherung. Einzelne Sozialdemokraten, wie Herbert Wehner (1906–1990), Hans- Jochen Vogel (Jahrgang 1926), Hermann Schmitt-Vockenhausen (1923-1979), Heinz Rapp (1924-2007), Helmut Schmidt (Jahrgang 1918) und Georg Leber (Jahrgang 1920), erkannten hier ein Versäumnis und engagierten sich aus persönlicher Überzeugung nachdrücklich und letztlich erfolgreich in diesem Prozess. Dadurch wurden die Vorbehalte und Angriffe von kirchlicher Seite gegen die SPD, gerade im Katholizismus, abgeschwächt, und es gelang der Partei, vor allem im katholischen Milieu deutlich an Stimmen zu gewinnen und letztlich auf Bundesebene mehrheitsfähig zu werden. Diese langwierige Entwicklung wird im Folgenden dargestellt, wobei der Schwerpunkt auf der wichtigeren zweiten Hälfte des 20. Jahrhunderts liegt. Als entscheidende Zäsur wird das Godesberger Programm von 1959 verstanden. I. Anhaltende Spannungen: Das Verhältnis von Sozialdemokratie und Arbeiterbewegung zu den Kirchen bis 1959 Während die mit dem Begriff Frühsozialismus -

Völkisch Writers and National Socialism

CULTURAL HISTORY AND LITERARY IMAGINATION This book provides a view of literary life under the Nazis, highlighting • Guy Tourlamain the ambiguities, rivalries and conflicts that determined the cultural climate of that period and beyond. Focusing on a group of writers – in particular, Hans Grimm, Erwin Guido Kolbenheyer, Wilhelm Schäfer, Emil Strauß, Börries Freiherr von Münchhausen and Rudolf Binding – it examines the continuities in völkisch-nationalist thought in Germany from c.1890 into the post-war period and the ways in which völkisch-nationalists identified themselves in opposition to four successive German regimes: the Kaiserreich, the Weimar Republic, the Third Reich and the Federal Republic. Although their work Völkisch predated Hitler’s National Socialist movement, their contribution to preparing the cultural climate for the rise of Nazism ensured them continued prominence in the Third Reich. Those who survived into the post-war era continued to represent the völkisch-nationalist worldview in the West German public sphere, opposing both Socialism and National Writers the Soviet and liberal-democratic models for Germany’s future. While not uncontroversial, they were able to achieve significant publishing success, suggesting that a demand existed for their works among the German public, stimulating debate about the nature of the recent past and its effect on Germany’s cultural and political identity and position in the world. Völkisch Writers and National Socialism Guy Tourlamain received his D.Phil. from Oxford University in 2007. He also spent time as a visiting student at the University of Gießen, A Study of Right-Wing Political Culture University of Hamburg and Humboldt University in Berlin as well as undertaking postdoctoral research at the German Literature in Germany, 1890–1960 Archive in Marbach am Neckar. -

Adenauer: "Stetigkeit in Der Politik". Die Protokolle Des CDU

Nr. 9: 14. März 1963 9 Bonn, Donnerstag 14. März 1963 Sprecher: Adenauer, Amrehn, Bauer, Blank, Blumenfeld, von Brentano, Burgbacher, Dichtet, Dufhues, Etzel, Fricke, Gurk, Heck, Katzer, Kraske, Krone, [Löhr], Lücke, Scheufeien, Schmidt, Schmücker, Stoltenberg. Innen- und außenpolitische Lage. Situation der CDU. Verschiedenes. Beginn: 11.00 Uhr Ende: 14.10 Uhr Adenauer: Meine Damen! Meine Herren! Unser Freund Johannes Albers ist von uns gegangen.1 (Die Anwesenden erheben sich.) Diejenigen von Ihnen, die den Feierlichkeiten in Köln gestern beigewohnt - auch der Feier im Gürzenich - und die Ansprachen gehört haben, die dort gehalten worden sind, werden einen Überblick bekommen haben über den politischen Werdegang unseres Freundes Albers. Der Zufall hat es gewollt, daß ich ihn wohl am längsten von allen gekannt habe. Ich kannte ihn seit dem Jahre 1919, als er zuerst nach Köln kam. Herr Albers hat in den schwierigen parteipolitischen Entwicklungen, die seit 1919 eingetreten waren - zunächst in der Weimarer Republik, dann unter dem Nationalsozialismus - und seit der Gründung der CDU immer offen und mannhaft seine innere Überzeugung bekannt und dementsprechend gehandelt. Wir alle verlieren in ihm nicht nur einen besonders wertvollen Mitarbeiter, sondern auch einen treuen Freund, dessen Andenken wir in Ehren halten werden. Sie haben sich von Ihren Plätzen erhoben. Ich danke Ihnen. Meine Damen und Herren! Ich bin von den Herren Kraske und Dufhues darauf aufmerksam gemacht worden, daß sich bei einer Bundesvorstandssitzung noch niemals so wenige Mitglieder entschuldigt haben wie heute. Es haben sich entschuldigt Herr Strauß - der regelmäßig eingeladen wurde -, dann die Herren von Hassel, Dr. Meyers und Dr. Fay, dessen Vertreter, Herr Löhr2, anwesend ist. -

"Zeichen Des Friedens Und Des Willens Zur Versöhnung"

„ZEICHEN DER MENSCHLICHKEIT UND DES WILLENS ZUR VERSÖHNUNG” 60 JAHRE CHARTA DER HEIMATVERTRIEBENEN Jörg-Dieter Gauger Hanns Jürgen Küsters (Hrsg.) IM IM ISBN 978-3-942775-17-5 PLENUM www.kas.de Diese Publikation dokumentiert die gleichnamige Vortrags- INHALT veranstaltung der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e. V. am 1. Juli 2010 in der Akademie der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, Berlin. 5 | VORWORT Die Beiträge wurden in der von den Autoren gewünschten 7 | ZUR EINFÜHRUNG Hans-Gert Pöttering Rechtschreibung abgedruckt. 13 | ERÖFFNUNGSREDE Volker Kauder 19 | DIE CHARTA – EIN AKT DER SELBSTÜBERWINDUNG Erika Steinbach 27 | FLUCHT, VERTREIBUNG, INTEGRATION – EIN FORSCHUNGSGESCHICHTLICHER RÜCKBLICK Horst Möller 43 | „WIR HEIMATVERTRIEBENEN VERZICHTEN AUF RACHE UND VERGELTUNG” – DIE STUTTGARTER CHARTA VOM 5./6. AUGUST 1950 ALS ZEITHISTORISCHES DOKUMENT Matthias Stickler 75 | SICHTWEISEN AUF DIE VERGANGENHEIT PODIUMSBEITRÄGE AUS DEUTSCHER, TSCHECHISCHER UND poLNISCHER SICHT 77 | EIN WICHTIGES DOKUMENT Manfred Kittel 81 | DIE CHARTA DER HEIMATVERTRIEBENEN UND DIE ENTWICKLUNG IN DER TSCHECHISCHEN REPUBLIK Kristina Kaiserová 85 | EIN KOMPLIZIERTER INTEGRATIONSPROZESS! Karol Sauerland Das Werk ist in allen seinen Teilen urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung ist ohne Zustimmung der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. 101 | SCHLUSSWORT unzulässig. Das gilt insbesondere für Vervielfältigungen, Übersetzungen, Hanns Jürgen Küsters Mikroverfilmungen und die Einspeicherung in und Verarbeitung durch elektronische Systeme. 104 | AUTOREN UND HERAUSGEBER © 2011, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung -

Gertrud Meyer Eine Politische Biografie

Universität Flensburg Gertrud Meyer Eine politische Biografie Inauguraldissertation Zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Philosophie vorgelegt der Universität Flensburg von Gertrud Lenz aus Cochem Gutachter Prof. Dr. Uwe Danker Prof. Dr. Robert Bohn im Dezember 2010 Inhaltsübersicht A. Einleitung .............................................................................................................................. 7 I. Thematische und methodische Aspekte .............................................................................. 7 II. Quellenlage ...................................................................................................................... 19 III. Sekundärliteratur ............................................................................................................ 22 B. Hauptteil .............................................................................................................................. 27 IV. Kindheit im Lübecker Arbeitermilieu ............................................................................ 27 V. Widerstand gegen den Nationalsozialismus in Lübeck ................................................... 39 VI. Exil in Norwegen ........................................................................................................... 83 VII. Assistentin des Mediziners und Psychoanalytikers Wilhelm Reich ........................... 212 VIII. Flüchtlingsarbeit und SAP-Arbeit in New York, Oslo und Stockholm .................... 240 IX. Kriegsende und Nachkriegszeit -

Bücherliste (PDF)

BIBLIOTHEK A Adenauer, Konrad (1966): Erinnerungen 1953-1955. 4 Bände: Deutsche Verlagsanstalt GmbH (2). Adenauer, Konrad (1975): Reden 1917-1967. Eine Auswahl. Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt. Adenauer, Konrad (1978, [1967): Erinnerungen 1955-1959. 2. Aufl. 4 Bände. Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt (3). Adenauer, Konrad (1978-1982, 1965-1968): Erinnerungen 1959-1963. Fragmente. 4 Bände. Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt (4). Adenauer, Konrad (1987): Erinnerungen 1945-1953. 6. Aufl. 4 Bände. Stuttgart: DVA (Erinnerungen / Konrad Adenauer, 1). Adenauer, Konrad; Mensing, Hans Peter; Morsey, Rudolf (1988): Rhöndorfer Ausgabe. Teegespräche 1959-1961. Rhöndorfer Ausgabe. Berlin: Siedler. Antje K. Pieper, Peter M. Lichtenberg Koninski, Wilfried E.; Antje K. Pieper, Peter M. Lichtenberg (Hg.) (1988): Ulrich Lohmar zum 60. Geburtstag Weggefährten erinnern sich. Arbeitsgemeinschaft "Bayerischer Wald", Freyung Arbeitsgemeinschaft "Bayerischer Wald", Freyung (Hg.) (1999): 30 Jahre erfolgreiche Strukturpolitik. Dokumentation über die Aufbauleistungenin der Region Unterer Bayerischer Wald 1967-1997. Unter Mitarbeit von Fritz Gerstl, Druni Irber, Barthl Kalb, Dr. Klaus Rose, Dr. Max Stadler, Jella Teuchner. Arnim, Hans Herbert von Arnim, Hans Herbert von (1997): Fetter Bauch regiert nicht gern. Die politische Klasse - selbstbezogen und abgehoben. München: Kindler. Atzenroth, Karl Atzenroth, Karl (1980): Zu meiner Zeit. Erinnerungen: atrioc-Verlag Bernhard Geue, Böblingen. Baring, Arnulf Schmidt, Claudius; Baring, Arnulf (1991): Heinrich Hellwege, der vergessene Gründervater. Ein politisches Lebensbild. Zugl.: Berlin, Freie Univ., Diss., 1990. Stade: Landschaftsverb. der Ehem. Herzogtümer Bremen und Verden (Schriftenreihe des Landschaftsverbandes der ehemaligen Herzogtümer Bremen und Verden, 4). B Baul, Hansjoachim Baul, Hansjoachim (Hg.) (1971): Carlo Schmid Bundestagsreden. mit einem Vorwort von Fritz Erler. 2. ergänzte Auflage: az studio bonn Pfattheicher & Reichardt Bonn. Becher, Walter Becher, Walter (Hg.) (1985): Der Blick aufs Ganze.