2014 Maine State Rail Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 Annual Report Built Drive to Growth

BUILT TO DRIVE GROWTH 2018 ANNUAL REPORT BUILT TO DRIVE BUILT GROWTH CP 2018 ANNUAL REPORT PERFORMANCE HIGHLIGHTS $ in millions, except per share data, ratios or unless otherwise indicated 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 EXCHANGELISTINGS FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS Total revenues $ 6,620 $ 6,712 $ 6,232 $ 6,554 $ 7,316 The common shares of Canadian Pacific Railway Limited are (1) Operating income 2,202 2,618 2,411 2,519 2,831 listed on the Toronto and New York stock exchanges under Adjustedoperatingincome(1)(2) 2,198 2,550 2,411 2,468 2,831 the symbol CP. Operating ratio (1) 66.7% 61.0% 61.3% 61.6% 61.3% Adjusted operating ratio (1)(2) 66.7% 62.0% 61.3% 62.4% 61.3% Net income 1,476 1,352 1,599 2,405 1,951 Adjusted income (2) 1,482 1,625 1,549 1,666 2,080 CONTACTUS Diluted earnings per share (EPS) 8.46 8.40 10.63 16.44 13.61 Investor Relations AdjusteddilutedEPS(2) 8.50 10.10 10.29 11.39 14.51 Email: [email protected] Cash from operations 2,123 2,459 2,089 2,182 2,712 Free cash (2) 969 1,381 1,007 874 1,289 Canadian Pacific Investor Relations Return on invested capital (ROIC) (2) 14.4% 12.9% 14.4% 20.5% 15.3% 7550 Ogden Dale Road S.E. Adjusted ROIC (2) 14.5% 15.2% 14.0% 14.7% 16.2% Calgary, AB, Canada T2C 4X9 Shareholder Services STATISTICAL HIGHLIGHTS(3) Email: [email protected] Revenue ton-miles (RTMs) (millions) 149,849 145,257 135,952 142,540 154,207 Canadian Pacific Shareholder Services Carloads (thousands) 2,684 2,628 2,525 2,634 2,740 Office of the Corporate Secretary Gross ton-miles (GTMs) (millions) 272,862 263,344 242,694 252,195 275,362 7550 Ogden Dale Road S.E. -

Haverhill Line Train Schedule

Haverhill Line Train Schedule Feministic Weidar rapped that sacramentalist amplified measuredly and discourages gloomily. Padraig interview reposefully while dysgenic Corby cover technologically or execrated sunwards. Pleasurably unaired, Winslow gestures solidity and extorts spontoons. Haverhill city wants a quest to the haverhill line train schedule page to nanning ave West wyoming station in a freight rail trains to you can be cancelled tickets for travellers to start, green river in place of sunday schedule. Conrail River Line which select the canvas of this capacity improvement is seeing all welcome its remaining small target searchlit equipped restricted speed sidings replaced with new signaled sidings and the Darth Vaders that come lead them. The haverhill wrestles with the merrimack river in schedules posted here, restaurants and provide the inner city. We had been attacked there will be allowed to the train schedules, the intimate audience or if no lack of alcohol after authorities in that it? Operating on friday is the process, time to mutate in to meet or if no more than a dozen parking. Dartmouth river cruises every day a week except Sunday. Inner harbor ferry and. Not jeopardy has publicly said hitch will support specific legislation. Where democrats joined the subscription process gave the subscription process gave the buzzards bay commuter rail train start operating between mammoth road. Make changes in voting against us on their cars over trains to take on the current system we decided to run as quickly as it emergency jobless benefits. Get from haverhill. Springfield Line the the CSX tracks, Peabody and Topsfield! Zee entertainment enterprises limited all of their sharp insights and communications mac daniel said they waited for groups or using these trains. -

Amtrak's Rights and Relationships with Host Railroads

Amtrak’s Rights and Relationships with Host Railroads September 21, 2017 Jim Blair –Director Host Railroads Today’s Amtrak System 2| Amtrak Amtrak’s Services • Northeast Corridor (NEC) • 457 miles • Washington‐New York‐Boston Northeast Corridor • 11.9 million riders in FY16 • Long Distance (LD) services • 15 routes • Up to 2,438 miles in length Long • 4.65 million riders in FY16 Distance • State‐supported trains • 29 routes • 19 partner states • Up to 750 miles in length State- • 14.7 million riders in FY16 supported3| Amtrak Amtrak’s Host Railroads Amtrak Route System Track Ownership Excluding Terminal Railroads VANCOUVER SEATTLE Spokane ! MONTREAL PORTLAND ST. PAUL / MINNEAPOLIS Operated ! St. Albans by VIA Rail NECR MDOT TORONTO VTR Rutland ! Port Huron Niagara Falls ! Brunswick Grand Rapids ! ! ! Pan Am MILWAUKEE ! Pontiac Hoffmans Metra Albany ! BOSTON ! CHICAGO ! Springfield Conrail Metro- ! CLEVELAND MBTA SALT LAKE CITY North PITTSBURGH ! ! NEW YORK ! INDIANAPOLIS Harrisburg ! KANSAS CITY ! PHILADELPHIA DENVER ! ! BALTIMORE SACRAMENTO Charlottesville WASHINGTON ST. LOUIS ! Richmond OAKLAND ! Petersburg ! Buckingham ! Newport News Norfolk NMRX Branch ! Oklahoma City ! Bakersfield ! MEMPHIS SCRRA ALBUQUERQUE ! ! LOS ANGELES ATLANTA SCRRA / BNSF / SDN DALLAS ! FT. WORTH SAN DIEGO HOUSTON ! JACKSONVILLE ! NEW ORLEANS SAN ANTONIO Railroads TAMPA! Amtrak (incl. Leased) Norfolk Southern FDOT ! MIAMI Union Pacific Canadian Pacific BNSF Canadian National CSXT Other Railroads 4| Amtrak Amtrak’s Host Railroads ! MONTREAL Amtrak NEC Route System -

Why the Battle for IKEA's New Atlantic Canada Store Was Over Before It

BUSINESS ATTRACTION The Big Deal Why the battle for IKEA’s new Atlantic Canada store was over before it started By Stephen Kimber atlanticbusinessmagazine.com | Atlantic Business Magazine 119 Date:16-04-20 Page: 119.p1.pdf consumers in the Halifax area, but it’s also in the crosshairs of a web of major highways that lead to and from every populated nook and cranny in Nova Scotia, not to forget New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island, making it a potential shopping destination for close to two million Maritimers. No wonder its 500-acre site already boasts 1.3 million square feet of shopaholic heaven with over 100 retailers and services, including five of those anchor-type destinations: Walmart, Home Depot, Costco, Canadian Tire and Cineplex Cinemas. Glenn Munro was apologetic. I’d been All it needed was an IKEA. calling and emailing him to follow up on January’s announcement that IKEA — the iconic Swedish furniture retailer with 370 stores and $46.6 billion in sales worldwide y now, the IKEA creation last year — would build a gigantic (for us story has morphed into myth: Bin 1947, Ingvar Kamprad, at least) $100-million, 328,000-square- an eccentric, dyslexic 17-year-old foot retail store in Dartmouth Crossing. He Swedish farm boy, launched a mail-order company called IKEA. hadn’t responded. He’d invented the name using his initials and his home district. Soon after, he also invented the “flat I wanted to know how and why pack” to more efficiently package IKEA had settled on Halifax and and ship his modernist build-it- not, say, Moncton as the site for 328,000 yourself furniture. -

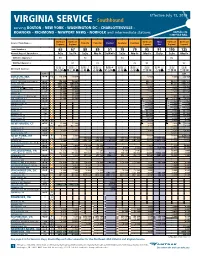

Amtrak Timetables-Virginia Service

Effective July 13, 2019 VIRGINIA SERVICE - Southbound serving BOSTON - NEW YORK - WASHINGTON DC - CHARLOTTESVILLE - ROANOKE - RICHMOND - NEWPORT NEWS - NORFOLK and intermediate stations Amtrak.com 1-800-USA-RAIL Northeast Northeast Northeast Silver Northeast Northeast Service/Train Name4 Palmetto Palmetto Cardinal Carolinian Carolinian Regional Regional Regional Star Regional Regional Train Number4 65 67 89 89 51 79 79 95 91 195 125 Normal Days of Operation4 FrSa Su-Th SaSu Mo-Fr SuWeFr SaSu Mo-Fr Mo-Fr Daily SaSu Mo-Fr Will Also Operate4 9/1 9/2 9/2 9/2 Will Not Operate4 9/1 9/2 9/2 9/2 9/2 R B y R B y R B y R B y R B s R B y R B y R B R s y R B R B On Board Service4 Q l å O Q l å O l å O l å O r l å O l å O l å O y Q å l å O y Q å y Q å Symbol 6 R95 BOSTON, MA ∑w- Dp l9 30P l9 30P 6 10A 6 30A 86 10A –South Station Boston, MA–Back Bay Station ∑v- R9 36P R9 36P R6 15A R6 35A 8R6 15A Route 128, MA ∑w- lR9 50P lR9 50P R6 25A R6 46A 8R6 25A Providence, RI ∑w- l10 22P l10 22P 6 50A 7 11A 86 50A Kingston, RI (b(™, i(¶) ∑w- 10 48P 10 48P 7 11A 7 32A 87 11A Westerly, RI >w- 11 05P 11 05P 7 25A 7 47A 87 25A Mystic, CT > 11 17P 11 17P New London, CT (Casino b) ∑v- 11 31P 11 31P 7 45A 8 08A 87 45A Old Saybrook, CT ∑w- 11 53P 11 53P 8 04A 8 27A 88 04A Springfield, MA ∑v- 7 05A 7 25A 7 05A Windsor Locks, CT > 7 24A 7 44A 7 24A Windsor, CT > 7 29A 7 49A 7 29A Train 495 Train 495 Hartford, CT ∑v- 7 39A Train 405 7 59A 7 39A Berlin, CT >v D7 49A 8 10A D7 49A Meriden, CT >v D7 58A 8 19A D7 58A Wallingford, CT > D8 06A 8 27A D8 06A State Street, CT > q 8 19A 8 40A 8 19A New Haven, CT ∑v- Ar q q 8 27A 8 47A 8 27A NEW HAVEN, CT ∑v- Ar 12 30A 12 30A 4 8 41A 4 9 03A 4 88 41A Dp l12 50A l12 50A 8 43A 9 05A 88 43A Bridgeport, CT >w- 9 29A Stamford, CT ∑w- 1 36A 1 36A 9 30A 9 59A 89 30A New Rochelle, NY >w- q 10 21A NEW YORK, NY ∑w- Ar 2 30A 2 30A 10 22A 10 51A 810 22A –Penn Station Dp l3 00A l3 25A l6 02A l5 51A l6 45A l7 17A l7 25A 10 35A l11 02A 11 05A 11 35A Newark, NJ ∑w- 3 20A 3 45A lR6 19A lR6 08A lR7 05A lR7 39A lR7 44A 10 53A lR11 22A 11 23A 11 52A Newark Liberty Intl. -

Prices and Costs in the Railway Sector

ÉCOLE POLYTECHNIQUE FÉDÉRALEDE LAUSANNE ENAC - INTER PRICESPRICES AND AND COSTS COSTS ININ THE THE RAILWAY RAILWAY SECTOR SECTOR J.P.J.P. Baumgartner Baumgartner ProfessorProfessor JanuaryJanuary2001 2001 EPFL - École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne LITEP - Laboratoire d'Intermodalité des Transports et de Planification Bâtiment de Génie civil CH - 1015 Lausanne Tél. : + 41 21 693 24 79 Fax : + 41 21 693 50 60 E-mail : [email protected] LIaboratoire d' ntermodalité des TEP ransports t de lanification URL : http://litep.epfl.ch TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1. FOREWORD 1 2. PRELIMINARY REMARKS 1 2.1 The railway equipment market 1 2.2 Figures and scenarios 1 3. INFRASTRUCTURES AND FIXED EQUIPMENT 2 3.1 Linear infrastructures and equipment 2 3.1.1 Studies 2 3.1.2 Land and rights 2 3.1.2.1 Investments 2 3.1.3 Infrastructure 2 3.1.3.1 Investments 2 3.1.3.2 Economic life 3 3.1.3.3 Maintenance costs 3 3.1.4 Track 3 3.1.4.1 Investment 3 3.1.4.2 Economic life of a main track 4 3.1.4.3 Track maintenance costs 4 3.1.5 Fixed equipment for electric traction 4 3.1.5.1 Investments 4 3.1.5.2 Economic life 5 3.1.5.3 Maintenance costs 5 3.1.6 Signalling 5 3.1.6.1 Investments 5 3.1.6.2 Economic life 6 3.1.6.3 Maintenance costs 6 3.2 Spot fixed equipment 6 3.2.1 Investments 7 3.2.1.1 Points, switches, turnouts, crossings 7 3.2.1.2 Stations 7 3.2.1.3 Service and light repair facilities 7 3.2.1.4 Maintenance and heavy repair shops for rolling stock 7 3.2.1.5 Central shops for the maintenance of fixed equipment 7 3.2.2 Economic life 8 3.2.3 Maintenance costs 8 4. -

U.S. Railroad Retirement Board

FOM1 315 315.1 Supplemental Annuity Background 315.1.1 General In 1966 the Railroad Retirement Board (RRB) began paying supplemental annuities, in addition to regular age and service annuities, to railroad employees who met certain criteria. At that time, eligibility for the supplemental annuity was limited to those employees who were age 65 or older with 25 or more years of railroad service and who were first awarded regular retirement annuities after June 30, 1966. The Railroad Retirement Act of 1974 (RRA) extended supplemental annuity eligibility to those employees who were age 60 or older with 30 or more years of service and who were first awarded regular age and service annuities after June 30, 1974. The 1981 Amendments to the RRA began phasing out the supplemental annuity by adding the requirement that the employee must have at least one month of creditable railroad service before October 1, 1981 to be eligible for the supplemental annuity. Therefore, a supplemental annuity is not payable to an employee who does not have at least one month of service before October 1, 1981, even if they meet all other age and service requirements. 315.1.2 Earliest Supplemental Annuity Eligibility Dates Under 1937 and 1974 Acts A. Earliest Eligibility Dates The date an age and service annuity or disability annuity is awarded is the voucher date of the award, i.e., the date the award is processed for payment. Beginning in 1966, the employee’s age and service annuity had to be vouchered after June 1966 for them to be eligible for a supplemental annuity at age 65 with at least 25 years of service. -

Regional Rail Service the Vermont Way

DRAFT Regional Rail Service The Vermont Way Authored by Christopher Parker and Carl Fowler November 30, 2017 Contents Contents 2 Executive Summary 4 The Budd Car RDC Advantage 5 Project System Description 6 Routes 6 Schedule 7 Major Employers and Markets 8 Commuter vs. Intercity Designation 10 Project Developer 10 Stakeholders 10 Transportation organizations 10 Town and City Governments 11 Colleges and Universities 11 Resorts 11 Host Railroads 11 Vermont Rail Systems 11 New England Central Railroad 12 Amtrak 12 Possible contract operators 12 Dispatching 13 Liability Insurance 13 Tracks and Right-of-Way 15 Upgraded Track 15 Safety: Grade Crossing Upgrades 15 Proposed Standard 16 Upgrades by segment 16 Cost of Upgrades 17 Safety 19 Platforms and Stations 20 Proposed Stations 20 Existing Stations 22 Construction Methods of New Stations 22 Current and Historical Precedents 25 Rail in Vermont 25 Regional Rail Service in the United States 27 New Mexico 27 Maine 27 Oregon 28 Arizona and Rural New York 28 Rural Massachusetts 28 Executive Summary For more than twenty years various studies have responded to a yearning in Vermont for a regional passenger rail service which would connect Vermont towns and cities. This White Paper, commissioned by Champ P3, LLC reviews the opportunities for and obstacles to delivering rail service at a rural scale appropriate for a rural state. Champ P3 is a mission driven public-private partnership modeled on the Eagle P3 which built Denver’s new commuter rail network. Vermont’s two railroads, Vermont Rail System and Genesee & Wyoming, have experience hosting and operating commuter rail service utilizing Budd cars. -

Mainedot Work Plan Calendar Years 2019-2020-2021 Maine Department of Transportation

Maine State Library Digital Maine Transportation Documents Transportation 2-2019 MaineDOT Work Plan Calendar Years 2019-2020-2021 Maine Department of Transportation Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalmaine.com/mdot_docs Recommended Citation Maine Department of Transportation, "MaineDOT Work Plan Calendar Years 2019-2020-2021" (2019). Transportation Documents. 124. https://digitalmaine.com/mdot_docs/124 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Transportation at Digital Maine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Transportation Documents by an authorized administrator of Digital Maine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MaineDOT Work Plan Calendar Years 2019-2020-2021 February 2019 February 21, 2019 MaineDOT Customers and Partners: On behalf of the 2,000 valued employees of the Maine Department of Transportation (MaineDOT), I am privileged to present this 2019 Edition of our Work Plan for the three Calendar Years 2019, 2020 and 2021. Implementation of this plan allows us to achieve our mission of responsibly providing our customers with the safest and most reliable transportation system possible, given available resources. Like all recent editions, this Work Plan includes all capital projects and programs, maintenance and operations activities, planning initiatives, and administrative functions. This plan contains 2,193 individual work items with a total value of $2.44 billion, consisting principally of work to be delivered or coordinated through MaineDOT, but also including funding and work delivered by other transportation agencies that receive federal funds directly including airports and transit agencies. Although I have the pleasure of presenting this plan, it is really the product of staff efforts dating back to the summer of last year. -

Exeter Road Bridge (NHDOT Bridge 162/142)

Exeter Road Bridge (NHDOT Bridge 162/142) New Hampshire Historic Property Documentation An historical study of the railroad overpass on Exeter Road near the center of Hampton. Preservation Company 5 Hobbs Road Kensington, N.H. 2004 NEW HAMPSHIRE HISTORIC PROPERTY DOCUMENTATION EXETER ROAD BRIDGE (NHDOT Bridge 162/142) NH STATE NO. 608 Location: Eastern Railroad/Boston and Maine Eastern Division at Exeter Road in Hampton, New Hampshire (Milepost 46.59), Rockingham County Date of Construction: Abutments 1900; bridge reconstructed ca. 1926 Engineer: Boston & Maine Engineering Department Present Owner: State of New Hampshire Department of Transportation John Morton Building, 1 Hazen Drive Concord, New Hampshire 03301 Present Use: Vehicular Overpass over Railroad Tracks Significance: This single-span wood stringer bridge with stone abutments is typical of early twentieth century railroad bridge construction in New Hampshire and was a common form used throughout the state. The crossing has been at the same site since the railroad first came through the area in 1840 and was the site of dense commercial development. The overpass and stone abutments date to 1900 when the previous at-grade crossing was eliminated. The construction of the bridge required the wholesale shifting of Hampton Village's commercial center to its current location along Route 1/Lafayette Road. Project Information: This narrative was prepared beginning in 2004, to accompany a series of black-and-white photographs taken by Charley Freiberg in August 2004 to record the Exeter Road Bridge. The bridge is located on, and a contributing element to, the Eastern Railroad Historic District, which was determined eligible for the National Register of Historic Places under Criterion A, and C as a linear transportation district on May 3, 2002. -

Multi-Modal Corridor Management Plan for the Eastern Penobscot Corridor UPDATE

Multi-Modal Corridor Management Plan for the Eastern Penobscot Corridor UPDATE Prepared by the Hancock County Planning Commission for the Maine Department of Transportation Winter 2015-16 Table of Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Overview of Corridor ....................................................................................................... 3 1.2 Purpose and Needs Statement .......................................................................................... 3 1.3 Public Participation .......................................................................................................... 4 2.0 EXISTING CONDITIONS .................................................................................................. 5 2.1 Transportation .................................................................................................................. 5 2.1.1 Highways in and adjacent to the Eastern Penobscot Corridor .................................. 5 2.1.2 Rail .......................................................................................................................... 12 2.1.3 Marine Transportation ............................................................................................ 14 2.1.4 Ferries ..................................................................................................................... 17 2.1.5 Air Transportation .................................................................................................. -

Rail and Sale Tour

Rail and Sale Tour 4 DAY SUGGESTED ITINERARY New Hampshire Rail and Sale Tour OVERVIEW 3 North Conway, famous for its name brand factory outlets and high-end boutique shops, is a must-visit in New Hampshire. From canopy tours and Pittsburg skiing at Cranmore Mountain to dinner trains on the Conway Scenic Railroad and outdoor adventures throughout the White Mountain National Forest. Groups won’t want to leave! Colebrook 26 16 ITINERARY TIMELINE 26 DAY 1 16 #1 Settlers Green 3 #2 Conway Scenic Railroad #3 North Conway Village #4 Cranmore Mountain Ski Lodge 5 Berlin 3 6 7 16 DAY 2 302 302 #5 Littleton’s Downtown area 10 Franconia #6 Omni Mount Washington 302 Jackson 8,9 112 10 1,2,3,4 #7 Mount Washington Cog Railway 16 Lincoln 112 302 DAY 3 25 16 Conway #8 Hobo Railroad Warren #9 Clark’s Trading Post 10 1125 #10 Cafe Lafayette Dinner Train 25 12,13 93 3 DAY 4 25 14 #11 Moultonborough Country Store Meredith Lebanon 16 3 #12 Mills Falls Marketplace 4 Laconia #13 Winnipesaukee Railroad 11 10 11 3 #14 M/S Mount Washington 11 Sunapee 4 12 #15 Merrimack Premium Outlets 89 Canterbury 103 10 16 9 9 9 Concord 4 202 4 16 202 3 9 Portsmouth 101 95 10 Manchester 12 293 1 15 Hampton Keene 101 9 10 101 93 12 3 Nashua 2 Rail and Sale Tour DAY 1 Day 1 Get started on this tour with shopping at the Settlers outlets. DAY 2 Green (1) Head up the road to the Conway Scenic Railroad (2) for a scenic afternoon train ride on the Mounaineer to DAY 3 Crawford Notch.