Two Van Gogh Fakes in the National Gallery of Art Washington?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pca Neighborhood Guide

PCA NEIGHBORHOOD GUIDE 1 INDEX VOCABULARY Useful everyday 4 phrases in French MAPS How to get to campus 5 from the two closest metro stations PHARMACIES A summary of pharmacies in Paris that are open 24/7 or 7 7-8 days a week SUPERMARKETS 8-9 Your guide in the jungle of French supermarkets EATING ORGANIC Where to find natural and 10 organic food in Paris MARKETS 11-13 Which markets to visit for fresh vegetables, fruits and other goods FITNESS & PARKS A selection of gyms to sweat and 14-15 parks to relax CANAL SAINT-MARTIN 16-17 A guide to one of our favorite areas of Paris AROUND SCHOOL Nearby restaurants, 18-23 cafés and bars ARRONDISSEMENTS GUIDE 25-44 Restaurants, bars, galleries and other places worth seeing in each district BANLIEUE GUIDE Places right outside of Paris that are 46-53 worth the trip 3 VOCABULARY USEFUL PHRASES Do you speak English? Do you have. ? Est-ce que vous parlez anglais? Avez-vous…? Could you repeat that, please? Where is. ? Pourriez-vous répéter, s’il vous Où est…? plaît? What street is the....on? Would you help me please? Dans quelle rue se trouve...? Pourriez-vous m’aider? What time does the restaurant Where can I find…? close? Où est-ce que je peux trouver...? À quelle heure le restaurant ferme? How much does . cost? Combien coûte…? Do you have any discounts for students? Where are the bathrooms? Avez-vous une réduction pour les Où sont les toilettes? étudiants? Yes // Oui Train station // Gare No // Non Bank // Banque Thank you // Merci Library // Bibliothèque Excuse me // Excusez-moi Bookstore // Librairie -

Mons 2015 Fera Fleurir La Jeunesse

TRIMESTRIEL N°27 _ HIVER 2014/15 STARWAW FANNY BOUYAGUI — L’artiste complice de Mons 2015 fera fleurir la jeunesse ÉDITION SPÉCIALE MONS 2015 Évènement culturel de l’année 6,50 € ISSN 2030-6849 www.wawmagazine.be n°27 EDITO Au travers de très nombreuses manifestations, allant d’expositions prestigieuses à des animations de rue, l’équipe de Mons 2015 entend offrir tout au long de l’année du plaisir, de la beauté et de la joie à la population locale et aux visiteurs belges et étrangers, que l’on attend nombreux. La qualité du projet culturel a été validée par les autorités communautaires qui ont décerné à la ville le titre de Capitale européenne de la Culture et a d’ores et déjà été récompensée par l’attribution récente du prix Mélina Mercouri (du nom de l’artiste grecque, Ministre de la Culture de son pays). © DR Mais si les pouvoirs publics (Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles, Région wallonne, Province du Hainaut, Ville de Mons) ont, en ces temps budgétaire- ment difficiles, alloué au projet d’importants crédits (gérés avec prudence par la Fondation Mons 2015), c’est que ce projet est certes d’abord culturel, mais pas uniquement. Il s’agit d’un investissement dont sont attendues des retombées qui dépasseront de beaucoup la mise initiale. Des retombées financières sont évidentes : des artistes et bien d’autres ressources hu- maines sont mobilisés pour l’occasion dans la région ; des recettes de billetterie et de vente de produits dérivés seront engrangées (l’exposition Van Gogh, par exemple, suscite d’ores et déjà un grand engouement) ; le chiffre d’affaires des cafés, restaurants, hôtels et de l’en- semble des commerces sera incontestablement boosté par l’afflux de visiteurs. -

Inventaire Des Archives De La Direction De La Restauration (1896-2001) IDENTITÉ Pierre De Spiegeler - Philippe Gémis - Michel Weyssow

Inventaire des archives de la direction de la Restauration (1896-2001) IDENTITÉ Pierre De Spiegeler - Philippe Gémis - Michel Weyssow Documentation ARCHIVES RÉGIONALES Inventaires 1 INVENTAIRE DES ARCHIVES - DGATLP 1896 - 2006 3 INVENTAIRE DES ARCHIVES DE LA DIRECTION DE LA RESTAURATION (1896 - 2001) de la direction générale de l’Aménagement du Territoire, du Logement et du Patrimoine, division du Patrimoine (MRW/DGATLP), devenue en 2008 la direction générale opérationnelle de l’Aménagement du Territoire, du Logement, du Patrimoine et de l’Énergie (SPW/DGO 4) 4 ARCHIVES RÉGIONALES Inventaires no 1 SPW/Éditions Secrétariat général / Département de la Communication Direction de l’Identité et des Publications (DIP) Place Joséphine-Charlotte, 2 – 5100 Namur En partenariat et sur l’initiative de la direction de la Documentation et des Archives régionales (DDAR) Éditeur responsable Sylvie Marique Secrétaire générale Supervision Jacques Moisse Inspecteur général Rédaction/recherche documentaire/direction d’ouvrage Philippe Gémis (DDAR) Pierre De Spiegeler (DDAR) Michel Weyssow Ligne éditoriale Jacques Vandenbroucke (DIP) Conception graphique Nathalie Lambrechts (DIP) Impression Direction de l’Édition (DGT) Diffusion SPW - Secrétariat général DIP - DDAR Dépôt légal : D/2016/11802/32 Toute reproduction totale ou partielle nécessite l’autorisation de l’éditeur responsable. Cet inventaire est consultable en ligne sur : www.wallonie.be/fr/publications/inventaire-des-archives-de-la-dgatlp-ndeg1 INVENTAIRE DES ARCHIVES - DGATLP 1896 - 2006 5 TABLE DES MATIERES AVANT-PROPOS 6 DESCRIPTION GÉNÉRALE 8 MRW/DGATLP/200104 . 8 I . IDENTIFICATION . 8 II . HISTOIRE DU PRODUCTEUR ET DES ARCHIVES . 8 III . CONTENU ET STRUCTURE . .9 . IV . CONSULTATION ET UTILISATION . 10. MRW/DGATLP/200406 . 11 I . -

1815, WW1 and WW2

Episode 2 : 1815, WW1 and WW2 ‘The Cockpit of Europe’ is how Belgium has understatement is an inalienable national often been described - the stage upon which characteristic, and fame is by no means a other competing nations have come to fight reliable measure of bravery. out their differences. A crossroads and Here we look at more than 50 such heroes trading hub falling between power blocks, from Brussels and Wallonia, where the Battle Belgium has been the scene of countless of Waterloo took place, and the scene of colossal clashes - Ramillies, Oudenarde, some of the most bitter fighting in the two Jemappes, Waterloo, Ypres, to name but a World Wars - and of some of Belgium’s most few. Ruled successively by the Romans, heroic acts of resistance. Franks, French, Holy Roman Empire, Burgundians, Spanish, Austrians and Dutch, Waterloo, 1815 the idea of an independent Belgium nation only floated into view in the 18th century. The concept of an independent Belgian nation, in the shape that we know it today, It is easy to forget that Belgian people have had little meaning until the 18th century. been living in these lands all the while. The However, the high-handed rule of the Austrian name goes back at least 2,000 years, when Empire provoked a rebellion called the the Belgae people inspired the name of the Brabant Revolution in 1789–90, in which Roman province Gallia Belgica. Julius Caesar independence was proclaimed. It was brutally was in no doubt about their bravery: ‘Of all crushed, and quickly overtaken by events in these people [the Gauls],’ he wrote, ‘the the wake of the French Revolution of 1789. -

Sur Les Musées

regards sur les musées ÉDITO SOMMAIRE 4 REGARD EN ARRIÈRE Débat sur la restitution des objets Nous sommes d’art : où en est-on ? 8 REGARD VERS DEMAIN tous conservateurs Aller au musée et prendre plaisir de la planète ! à voir et apprendre 10 REGARD D’UN TROISIÈME TYPE BD, galeries, musées. Chacun sa route, chacun son chemin 14 REGARD D’UN GRAND TÉMOIN François Mairesse : “ Le musée est une rencontre qui peut changer votre vie ! ” 18 REGARD ARDENT Les musées liégeois détenteurs © SANDRINE MOSSIAT© JACQUES REMACLE de trésors ADMINISTRATEUR-DÉLÉGUÉ ARTS & PUBLICS 20 REGARD OU PAS REGARD Où vont les femmes ? Au musée ! C’est l’urgence climatique. Sauvons notre planète, notre civilisation, notre humanité et celle des générations à venir ! Il est sain que l’opinion publique exprime son point 22 UN AUTRE REGARD de vue, affirme la nécessité d’une évolution rapide dans un domaine où les décisions Divagations et interprétations sont soumises aux influences des lobbys, du monde de la finance et aux compromis qui annihilent parfois l’efficacité des mesures prises. Cette vague de protestation est 27 REGARD NEUF en soi très bonne pour le climat ambiant. Micro-Folie mais grande pédagogie On aimerait mettre la planète au musée. Ralentir son rythme, l’observer, la soigner, la faire participer, la faire évoluer. Elle ne sortirait peut-être pas indemne 28 REGARD D’ARTISTE de l’expérience, mais ses visiteurs prendraient peut-être conscience de la nécessité La fille du Barrow de mieux la préserver et de sa valeur. 30 AU CENTRE DES REGARDS Comme le dit le professeur François Mairesse dans l’interview qu’il nous a accordée, Focus : Grand-Place et lieux insolites “ on ne va pas dans un musée de science pour y glaner des informations précises sur le réchauffement climatique, mais pour susciter un certain nombre de réflexions ”. -

Chemin Des Peintres

Le « chemin des peintres » The painters pathway est un itinéraire culturel is a historic cultural historique des plus grands route of the main peintres paysagistes, pre impressionists, pré-impressionnistes, impressionists and post impressionnistes et post- impressionists painters. impressionnistes. Ces sites These immortalized sites immortalisés sont répartis sur are spread out through l’ensemble de la commune. the whole village. SUGGESTION DE SUGGESTION OF DEUX PARCOURS TWO ROUTES EN ROUGE ET VERT IN RED AND GREEN PARCOURS ROUGE RED TRIP Une boucle pédestre de deux A pedestrian circuit of two hours, heures, autour de l’église d’Auvers- around the church will help to sur-Oise vous permet de découvrir discover places painted by Vincent les lieux peints par Vincent van van Gogh, walking until you come Gogh en allant jusque sur la to the graves of the two Van Gogh tombe des frères Van Gogh. Téléchargeable gratuitement à download, free of charge, the application Van Gogh Van Gogh Natures est un guide Natures, a geolocation multimédia géolocalisé. based multimedia guide. PARCOURS VERT GREEN TRIP Un autre trajet par la vieille rue en Another two and a half hours direction de Pontoise vous donne tour using the old road accès en deux heures trente in direction of Pontoise open minutes, à mille ans d’Histoire the door to a thousand years of dans ce véritable village History in the veritable d’artistes. artist’s village. 8 Paysage au Valhermeil Le jardin de Daubigny 24 Camille Pissarro Vincent van Gogh 9 Rue des roches Église d’Auvers 25 du Valhermeil -

The New Yorker

Kindle Edition, 2015 © The New Yorker COMMENT HARSH TALK BY MARGARET TALBOT Three years ago, after the reëlection of Barack Obama, a rueful Republican National Committee launched an inquiry into where the Party had gone wrong. Researchers for the Growth & Opportunity Project contacted more than twenty- six hundred people—voters, officeholders, Party operatives —conducted focus groups, and took polls around the country. The resulting report is a bracingly forthright piece of self-criticism that took the G.O.P. to task for turning off young voters, minorities, and women. A key finding was that candidates needed to curb the harsh talk about immigration. Mitt Romney’s call for “self-deportation” was loser rhetoric. Making people feel that “a GOP nominee or candidate does not want them in the United States” was poor politics. The report offered one specific policy recommendation: “We must embrace and champion comprehensive immigration reform. If we do not, our Party’s appeal will continue to shrink to its core constituencies.” None of the current Republican Presidential hopefuls seem to have taken that counsel to heart. Donald Trump, the front-runner, wouldn’t, of course. “The Hispanics love me,” he claims, despite the fact that he proposes building a wall on the Mexican border to keep out people he equates with “criminals, drug dealers, rapists.” Ben Carson takes issue with Trump’s stance, sort of. “It sounds really cool, you know, ‘Let’s just round them all up and send them back,’ ” he said. But it would cost too much, so he advocates deploying armed drones at the border. -

Reiseziel Impressionismus

DE_GUIDE_IMP_1.pdf 1 05/10/12 15:45 C M J CM MJ CJ CMJ N DE_GUIDE_IMP_2.pdf 1 05/10/12 15:32 C M J CM MJ CJ CMJ N DE_GUIDE_IMP_3.pdf 1 05/10/12 15:32 und Paris Volksvernügen, mit C M J CM MJ CJ Auf den Spuren von CMJ N Im Herzen der Landschaft – mit Die neue Malerei – mit DE_GUIDE_IMP_4.pdf 1 05/10/12 15:31 Musée de l’Orangerie Musée d’Orsay Musée Marmottan Monet MUSÉE DE L’ORANGERIE Im Musée d‘Orsay sind zu bewundern: La Gare Saint-Lazare, La Pie, Champs de coquelicots und Paris sowie 5 Gemälde aus der Serie, die Monet der gotischen Kathedrale in Rouen gewidmet hat, und im Musée de l’Orangerie das große Wand- C Zwischen Claude Monet und der Ile-de-France bild mit den Seerosen, das der Künstler dem M französischen Staat als Schenkung hinterlas- (der Region rund um Paris) gab es eine lange sen hat. J Liebesgeschichte. CM Es sind insgesamt 8 Seerosengemälde, beste- Seine Wiege stand in Paris, und dort lernte er MJ hend aus 22 Tafeln, in Panoramaform, unter- auch Renoir und Bazille kennen. Er malte gebracht in 2 ovalen, durch die zentrale Glas- CJ vorzugsweise Szenen des täglichen Lebens, kuppel von Tageslicht durchfluteten Sälen. CMJ etwa den Bahnhof Saint Lazare, die Rue Montor- Das Ganze wirkt wie ein visuelles Gedicht zu N gueil ... Ehren der Begegnung von Licht, Wasser und Pflanzenwelt, 200 m² voller Farben, eines der Seiner Inspiration und dem mäandernden monumentalsten Kunstwerke der Moderne. Verlauf der Seine folgend, ließ er sich in Argen- Das Museum bietet daneben noch andere teuil und später in Vétheuil nieder, dem letzten Schätze, etwa jene der Kollektion Walter- Ort innerhalb der Ile-de-France vor Giverny. -

Faculdade De Filosofia E Ciências Humanas Programa De Pós-Graduação Em História Mestrado Em História

FACULDADE DE FILOSOFIA E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM HISTÓRIA MESTRADO EM HISTÓRIA JÉSSICA TUANY WIADETSKI A ARTE PARA O POVO POR MEIO DAS GRAVURAS DO CLUBE DE GRAVURA DE PORTO ALEGRE E DO CLUB DE GRABADO DE MONTEVIDEO Porto Alegre 2018 A ARTE PARA O POVO POR MEIO DAS GRAVURAS DO CLUBE DE GRAVURA DE PORTO ALEGRE E DO CLUB DE GRABADO DE MONTEVIDEO Dissertação apresentada como requisito parcial para obtenção de grau de Mestre pelo Programa de Pós-Graduação em História da Escola de Humanidades da Pontifícia Universidade do Rio Grande do Sul. Orientadora: Professora Dra. Carolina Martins Etcheverry Porto Alegre 2018 JÉSSICA TUANY WIADETSKI A ARTE PARA O POVO POR MEIO DAS GRAVURAS DO CLUBE DE GRAVURA DE PORTO ALEGRE E DO CLUB DE GRABADO DE MONTEVIDEO Dissertação apresentada como requisito parcial para obtenção de grau de Mestre pelo Programa de Pós-Graduação em História da Escola de Humanidades da Pontifícia Universidade do Rio Grande do Sul. BANCA EXAMINADORA ____________________________________________ Professora Dra. Carolina Martins Etcheverry (Orientadora) – PUCRS ____________________________________________ Professora Dra. Maria Lúcia Bastos Kern – PUCRS ____________________________________________ Professora Dra. Blanca Brites – UFRGS Porto Alegre 2018 Ao meu, para sempre amado, Lupicínio (in memoriam). Àquele que sempre se faz presente em todos os momentos da minha vida, e que sem ele essa pesquisa não seria possível, Rafael Fagundes dos Santos. AGRADECIMENTOS De longe esta pesquisa não foi um trabalho individual, tornou-se possível graças ao envolvimento de muitas pessoas, direta ou indiretamente. Gostaria de agradecer primeiramente ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em História da Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul, o fato de ter aceitado este projeto de pesquisa. -

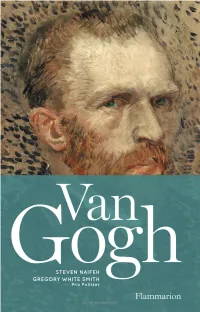

Van Gogh - Dynamic Layout 152X × 240X

Extrait de la publication Meta-systems - 02-07-13 16:52:28 FL1523 U000 - Oasys 19.00x - Page 3 - BAT Van Gogh - Dynamic layout 152x × 240x Van Gogh Meta-systems - 02-07-13 16:52:28 FL1523 U000 - Oasys 19.00x - Page 4 - BAT Van Gogh - Dynamic layout 152x × 240x Meta-systems - 02-07-13 16:52:28 FL1523 U000 - Oasys 19.00x - Page 5 - BAT Van Gogh - Dynamic layout 152x × 240x Steven Naifeh et Gregory White Smith Van Gogh Traduit de l’anglais (États-Unis) par Isabelle D. Taudière avec la collaboration de Lucile Débrosse Flammarion Meta-systems - 02-07-13 16:52:28 FL1523 U000 - Oasys 19.00x - Page 6 - BAT Van Gogh - Dynamic layout 152x × 240x Les citations de la correspondance de Van Gogh sont extraites de l’édition critique illustrée en six volumes, Actes Sud, 2009, partie intégrante du projet « Lettres de Van Gogh » réalisé sous les auspices du Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, et du Huygens Institute, La Haye, qui s’accompagne d’une édi- tion web en anglais : www.vangoghletters.org. © 2009 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, pour la traduction française des lettres écrites en néerlandais. Titre original : Van Gogh. The life. Copyright © 2011 by Woodward/White, Inc. Maps copyright © 2011 by David Lindroth, Inc. © Flammarion, 2013, pour la traduction française. ISBN : 978-2-0812-7035-0 Meta-systems - 02-07-13 16:52:29 FL1523 U000 - Oasys 19.00x - Page 7 - BAT Van Gogh - Dynamic layout 152x × 240x Nous dédions avec gratitude ce livre à nos mères, Marion Naifeh et Kathryn White Smith, qui nous ont initiés à la joie de l’art, et à tous les artistes de l’école Julliard, qui ont mis tant de joie dans notre vie. -

Kunstenaar Uit Mededogen

TENTOONSTELLING 14 KUNSTENAAR UIT MEDEDOGEN L’usine de coke Le Gargane à Flénu is een Van Gogh in de Borinage, van de weinige overgeleverde tekeningen uit de tijd dat Van Gogh in de Borinage verbleef. Het vergde dus enige creativiteit van curator de geboorte Sjraar van Heugten om met de tentoonstelling in het BAM (Beaux-Arts Mons) te laten zien van een kunstenaar dat Van Goghs kunstenaarsleven hier ontkiemde. HARDE TIJDEN ”Niets dan een beetje rook uit de schoorsteen Wilde hij er aanvankelijk nog de Bijbel verspreiden, gaan- zien de voorbijgangers voor ze hun weg vervolgen, maar aan deweg bood hij vooral troost. Als hij Hard Times van Charles het groot vuur in mijn ziel komen ze zich niet warmen,” Dickens leest, ziet hij de parallellen. Later zou de lectuur van schreef Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) naar zijn broer Theo Germinal van Emile Zola herinneringen oproepen aan zijn in de brief uit juli 1880 die het begin van zijn carrière als ervaringen in de Borinage. kunstenaar zou markeren. In de van de rook grauwe Pays In Cuesmes (Bergen), een ander dorp in de Borinage, Noir had hij zijn roeping van kunstenaar gevonden. Eerdere verbleef hij bij de familie Decrucq, waar nu het Maison pogingen om carrière te maken in de internationaal gere- Van Gogh is. Het kamertje dat hij deelde met de kinderen puteerde kunsthandel van zijn ooms Goupil & Cie in Den werd zijn eerste atelier. Uit mededogen begon hij daar de Haag, Parijs of Londen, of als evangelist in de dorpen rond mijnwerkers te tekenen die naar hun werk vertrokken. -

Where Van Gogh Comes to Life a Journey to the Landmark Places Proud of Their Legacies As Artistic Settings for the Dutch Painter

C M Y K Sxxx,2015-12-27,TR,001,Bs-4C,E1_K1 10 FOOTSTEPS In Prague, a search for Kafka’s inspirations. 6 HEADS UP The liquor gets local in Iceland. 14 36 HOURS Exploring Warsaw, a chic new cultural capital. DISCOVERY ADVENTURE ESCAPE SUNDAY, DECEMBER27, 2015 K ALEX CRETEY-SYSTERMANS FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES Where van Gogh Comes to Life A journey to the landmark places proud of their legacies as artistic settings for the Dutch painter. House once stood, the sun-drenched Gauguin, and sliced a blade through his own Paris and Arles and St. Rémy in Provence, A vineyard as seen in By NINA SIEGAL Provençal home that was the subject of his ear, before admitting himself to the local and ultimately to the Parisian suburb of Au- van Gogh’s “Vignes Rouges” A few months ago, I stood at the corner of a 1888 oil painting, where he took a period of mental hospital. vers-sur-Oise, where his life was cut short landscape, with tall, elegant busy roundabout called Place Lamartine, “enforced rest” as he put it, in a pale violet- From March to August, I traveled to in his 37th year. cypresses near St.-Rémy- across from the Roman gates leading into walled “Bedroom” he depicted in oil paint- many of the landmarks of van Gogh’s artis- I was on the trail of the artist during Van de-Provence, France. Arles in southern France, on a spot that was ings three times that year. tic life, beginning in the Belgian mining Gogh Europe 2015, the year that commemo- pivotal in the life of Vincent van Gogh.