Photon Energy Upconversion Through Thermal Radiation with the Power Efficiency Reaching 16%

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Article Soot Photometer Using Supervised Machine Learning

Atmos. Meas. Tech., 12, 3885–3906, 2019 https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-12-3885-2019 © Author(s) 2019. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Classification of iron oxide aerosols by a single particle soot photometer using supervised machine learning Kara D. Lamb1,2 1Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, CO, USA 2NOAA Earth System Research Laboratory Chemical Sciences Division, Boulder, CO, USA Correspondence: Kara D. Lamb ([email protected]) Received: 15 March 2019 – Discussion started: 22 March 2019 Revised: 20 June 2019 – Accepted: 21 June 2019 – Published: 15 July 2019 Abstract. Single particle soot photometers (SP2) use laser- each class are compared with the true class for those particles induced incandescence to detect aerosols on a single particle to estimate generalization performance. While the specific basis. SP2s that have been modified to provide greater spec- class approach performed well for rBC and Fe3O4 (≥ 99 % tral contrast between their narrow and broad-band incandes- of these aerosols are correctly identified), its classification of cent detectors have previously been used to characterize both other aerosol types is significantly worse (only 47 %–66 % refractory black carbon (rBC) and light-absorbing metallic of other particles are correctly identified). Using the broader aerosols, including iron oxides (FeOx). However, single par- class approach, we find a classification accuracy of 99 % for ticles cannot be unambiguously identified from their incan- FeOx samples measured in the laboratory. The method al- descent peak height (a function of particle mass) and color lows for classification of FeOx as anthropogenic or dust-like ratio (a measure of blackbody temperature) alone. -

Introduction 1

1 1 Introduction . ex arte calcinati, et illuminato aeri [ . properly calcinated, and illuminated seu solis radiis, seu fl ammae either by sunlight or fl ames, they conceive fulgoribus expositi, lucem inde sine light from themselves without heat; . ] calore concipiunt in sese; . Licetus, 1640 (about the Bologna stone) 1.1 What Is Luminescence? The word luminescence, which comes from the Latin (lumen = light) was fi rst introduced as luminescenz by the physicist and science historian Eilhardt Wiede- mann in 1888, to describe “ all those phenomena of light which are not solely conditioned by the rise in temperature,” as opposed to incandescence. Lumines- cence is often considered as cold light whereas incandescence is hot light. Luminescence is more precisely defi ned as follows: spontaneous emission of radia- tion from an electronically excited species or from a vibrationally excited species not in thermal equilibrium with its environment. 1) The various types of lumines- cence are classifi ed according to the mode of excitation (see Table 1.1 ). Luminescent compounds can be of very different kinds: • Organic compounds : aromatic hydrocarbons (naphthalene, anthracene, phenan- threne, pyrene, perylene, porphyrins, phtalocyanins, etc.) and derivatives, dyes (fl uorescein, rhodamines, coumarins, oxazines), polyenes, diphenylpolyenes, some amino acids (tryptophan, tyrosine, phenylalanine), etc. + 3 + 3 + • Inorganic compounds : uranyl ion (UO 2 ), lanthanide ions (e.g., Eu , Tb ), doped glasses (e.g., with Nd, Mn, Ce, Sn, Cu, Ag), crystals (ZnS, CdS, ZnSe, CdSe, 3 + GaS, GaP, Al 2 O3 /Cr (ruby)), semiconductor nanocrystals (e.g., CdSe), metal clusters, carbon nanotubes and some fullerenes, etc. 1) Braslavsky , S. et al . ( 2007 ) Glossary of terms used in photochemistry , Pure Appl. -

7. Gamma and X-Ray Interactions in Matter

Photon interactions in matter Gamma- and X-Ray • Compton effect • Photoelectric effect Interactions in Matter • Pair production • Rayleigh (coherent) scattering Chapter 7 • Photonuclear interactions F.A. Attix, Introduction to Radiological Kinematics Physics and Radiation Dosimetry Interaction cross sections Energy-transfer cross sections Mass attenuation coefficients 1 2 Compton interaction A.H. Compton • Inelastic photon scattering by an electron • Arthur Holly Compton (September 10, 1892 – March 15, 1962) • Main assumption: the electron struck by the • Received Nobel prize in physics 1927 for incoming photon is unbound and stationary his discovery of the Compton effect – The largest contribution from binding is under • Was a key figure in the Manhattan Project, condition of high Z, low energy and creation of first nuclear reactor, which went critical in December 1942 – Under these conditions photoelectric effect is dominant Born and buried in • Consider two aspects: kinematics and cross Wooster, OH http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arthur_Compton sections http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=22551 3 4 Compton interaction: Kinematics Compton interaction: Kinematics • An earlier theory of -ray scattering by Thomson, based on observations only at low energies, predicted that the scattered photon should always have the same energy as the incident one, regardless of h or • The failure of the Thomson theory to describe high-energy photon scattering necessitated the • Inelastic collision • After the collision the electron departs -

Photon Cross Sections, Attenuation Coefficients, and Energy Absorption Coefficients from 10 Kev to 100 Gev*

1 of Stanaaros National Bureau Mmin. Bids- r'' Library. Ml gEP 2 5 1969 NSRDS-NBS 29 . A111D1 ^67174 tioton Cross Sections, i NBS Attenuation Coefficients, and & TECH RTC. 1 NATL INST OF STANDARDS _nergy Absorption Coefficients From 10 keV to 100 GeV U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS T X J ". j NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS 1 The National Bureau of Standards was established by an act of Congress March 3, 1901. Today, in addition to serving as the Nation’s central measurement laboratory, the Bureau is a principal focal point in the Federal Government for assuring maximum application of the physical and engineering sciences to the advancement of technology in industry and commerce. To this end the Bureau conducts research and provides central national services in four broad program areas. These are: (1) basic measurements and standards, (2) materials measurements and standards, (3) technological measurements and standards, and (4) transfer of technology. The Bureau comprises the Institute for Basic Standards, the Institute for Materials Research, the Institute for Applied Technology, the Center for Radiation Research, the Center for Computer Sciences and Technology, and the Office for Information Programs. THE INSTITUTE FOR BASIC STANDARDS provides the central basis within the United States of a complete and consistent system of physical measurement; coordinates that system with measurement systems of other nations; and furnishes essential services leading to accurate and uniform physical measurements throughout the Nation’s scientific community, industry, and com- merce. The Institute consists of an Office of Measurement Services and the following technical divisions: Applied Mathematics—Electricity—Metrology—Mechanics—Heat—Atomic and Molec- ular Physics—Radio Physics -—Radio Engineering -—Time and Frequency -—Astro- physics -—Cryogenics. -

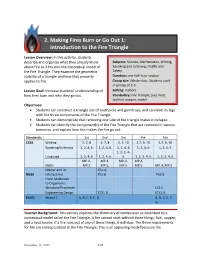

2. Making Fires Burn Or Go out 1: Introduction to the Fire Triangle

2. Making Fires Burn or Go Out 1: Introduction to the Fire Triangle Lesson Overview: In this activity, students describe and organize what they already know Subjects: Science, Mathematics, Writing, about fire so it fits into the conceptual model of Speaking and Listening, Health and the Fire Triangle. They examine the geometric Safety stability of a triangle and how that property Duration: one half-hour session applies to fire. Group size: Whole class. Students work in groups of 2-3. Lesson Goal: Increase students’ understanding of Setting: Indoors how fires burn and why they go out. Vocabulary: Fire Triangle, fuel, heat, ignition, oxygen, model Objectives: • Students can construct a triangle out of toothpicks and gumdrops, and can label its legs with the three components of the Fire Triangle. • Students can demonstrate that removing one side of the triangle makes it collapse. • Students can identify the component(s) of the Fire Triangle that are removed in various scenarios, and explain how this makes the fire go out. Standards: 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th CCSS Writing 2, 7, 8 2, 7, 8 2, 7, 10 2,7, 9, 10 2,7, 9, 10 Speaking/Listening 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 3, 4, Language 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 4, 6 6 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 MP.4, MP.4, MP.4, MP.4, Math MP.5 MP.5, MP.5 MP.5 MP.4, MP.5 Matter and Its PS1.A, NGSS Interactions PS1.B PS1.B From Molecules to Organisms: Structure/Processes LS1.C Engineering Design ETS1.B ETS1.B EEEGL Strand 1 A, B, C, E, F, G A, B, C, E, F, G Teacher Background: This activity explores the chemistry of combustion as described by a conceptual model called the Fire Triangle. -

Energy Efficiency Lighting Hearing Committee On

S. HRG. 110–195 ENERGY EFFICIENCY LIGHTING HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND NATURAL RESOURCES UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION TO RECEIVE TESTIMONY ON THE STATUS OF ENERGY EFFICIENT LIGHT- ING TECHNOLOGIES AND ON S. 2017, THE ENERGY EFFICIENT LIGHT- ING FOR A BRIGHTER TOMORROW ACT SEPTEMBER 12, 2007 ( Printed for the use of the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 39–385 PDF WASHINGTON : 2007 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 11:58 Feb 20, 2008 Jkt 040443 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 G:\DOCS\39385.XXX SENERGY2 PsN: MONICA COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND NATURAL RESOURCES JEFF BINGAMAN, New Mexico, Chairman DANIEL K. AKAKA, Hawaii PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico BYRON L. DORGAN, North Dakota LARRY E. CRAIG, Idaho RON WYDEN, Oregon LISA MURKOWSKI, Alaska TIM JOHNSON, South Dakota RICHARD BURR, North Carolina MARY L. LANDRIEU, Louisiana JIM DEMINT, South Carolina MARIA CANTWELL, Washington BOB CORKER, Tennessee KEN SALAZAR, Colorado JOHN BARRASSO, Wyoming ROBERT MENENDEZ, New Jersey JEFF SESSIONS, Alabama BLANCHE L. LINCOLN, Arkansas GORDON H. SMITH, Oregon BERNARD SANDERS, Vermont JIM BUNNING, Kentucky JON TESTER, Montana MEL MARTINEZ, Florida ROBERT M. SIMON, Staff Director SAM E. FOWLER, Chief Counsel FRANK MACCHIAROLA, Republican Staff Director JUDITH K. PENSABENE, Republican Chief Counsel (II) VerDate 0ct 09 2002 11:58 Feb 20, 2008 Jkt 040443 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 G:\DOCS\39385.XXX SENERGY2 PsN: MONICA C O N T E N T S STATEMENTS Page Bingaman, Hon. -

!History of Lightingv2.Qxd

CONTENTS Introduction 3 The role of lighting in modern society 3 1. The oldest light sources 4 Before the advent of the lamp 4 The oldest lamps 4 Candles and torches 5 Further development of the oil lamp 6 2. Gaslight 9 Introduction 9 Early history 9 Gas production 10 Gaslight burners 10 The gas mantle 11 3. Electric lighting before the incandescent lamp 14 Introduction 14 Principle of the arc lamp 15 Further development of the arc lamp 16 Applications of the arc lamp 17 4. The incandescent lamp 20 The forerunners 20 The birth of the carbon-filament lamp 22 Further development of the carbon-filament lamp 25 Early metal-filament lamps 27 The Nernst lamp 28 The birth of the tungsten-filament lamp 29 Drawn tungsten filaments 30 Coiled filaments 30 The halogen incandescent lamp 31 5. Discharge lamps 32 Introduction 32 The beginning 32 High-voltage lamps 33 Early low-pressure mercury lamps 34 The fluorescent lamp 35 High-pressure mercury lamps 36 Sodium lamps 37 The xenon lamp 38 6. Electricity production and distribution 39 Introduction 39 Influence machines and batteries 39 Magneto-electric generators 40 Self-exciting generators 41 The oldest public electricity supply systems 41 The battle of systems 42 The advent of modern a.c. networks 43 The History of Light and Lighting While the lighting industry is generally recognized as being born in 1879 with the introduction of Thomas Alva Edison’s incandescent light bulb, the real story of light begins thousands of years earlier. This brochure was developed to provide an extensive look at one of the most important inventions in mankind’s history: artificial lighting. -

Chapter 30: Quantum Physics ( ) ( )( ( )( ) ( )( ( )( )

Chapter 30: Quantum Physics 9. The tungsten filament in a standard light bulb can be considered a blackbody radiator. Use Wien’s Displacement Law (equation 30-1) to find the peak frequency of the radiation from the tungsten filament. −− 10 1 1 1. (a) Solve Eq. 30-1 fTpeak =×⋅(5.88 10 s K ) for the peak frequency: =×⋅(5.88 1010 s−− 1 K 1 )( 2850 K) =× 1.68 1014 Hz 2. (b) Because the peak frequency is that of infrared electromagnetic radiation, the light bulb radiates more energy in the infrared than the visible part of the spectrum. 10. The image shows two oxygen atoms oscillating back and forth, similar to a mass on a spring. The image also shows the evenly spaced energy levels of the oscillation. Use equation 13-11 to calculate the period of oscillation for the two atoms. Calculate the frequency, using equation 13-1, from the inverse of the period. Multiply the period by Planck’s constant to calculate the spacing of the energy levels. m 1. (a) Set the frequency T = 2π k equal to the inverse of the period: 1 1k 1 1215 N/m f = = = =4.792 × 1013 Hz Tm22ππ1.340× 10−26 kg 2. (b) Multiply the frequency by Planck’s constant: E==×⋅ hf (6.63 10−−34 J s)(4.792 × 1013 Hz) =× 3.18 1020 J 19. The light from a flashlight can be considered as the emission of many photons of the same frequency. The power output is equal to the number of photons emitted per second multiplied by the energy of each photon. -

The Basic Interactions Between Photons and Charged Particles With

Outline Chapter 6 The Basic Interactions between • Photon interactions Photons and Charged Particles – Photoelectric effect – Compton scattering with Matter – Pair productions Radiation Dosimetry I – Coherent scattering • Charged particle interactions – Stopping power and range Text: H.E Johns and J.R. Cunningham, The – Bremsstrahlung interaction th physics of radiology, 4 ed. – Bragg peak http://www.utoledo.edu/med/depts/radther Photon interactions Photoelectric effect • Collision between a photon and an • With energy deposition atom results in ejection of a bound – Photoelectric effect electron – Compton scattering • The photon disappears and is replaced by an electron ejected from the atom • No energy deposition in classical Thomson treatment with kinetic energy KE = hν − Eb – Pair production (above the threshold of 1.02 MeV) • Highest probability if the photon – Photo-nuclear interactions for higher energies energy is just above the binding energy (above 10 MeV) of the electron (absorption edge) • Additional energy may be deposited • Without energy deposition locally by Auger electrons and/or – Coherent scattering Photoelectric mass attenuation coefficients fluorescence photons of lead and soft tissue as a function of photon energy. K and L-absorption edges are shown for lead Thomson scattering Photoelectric effect (classical treatment) • Electron tends to be ejected • Elastic scattering of photon (EM wave) on free electron o at 90 for low energy • Electron is accelerated by EM wave and radiates a wave photons, and approaching • No -

The Electric-Lamp Industry

Massachusetts Institute of Technology Studies of Innovation • GiSma,..=("EaEssormat THE MACMILLAN COMPANY THE ELECTRIC-LAMP INDUSTRY: NEW YORK a BOSTON a CHICAGO DALLAS • ATLANTA • SAN FRANCISCO MACMILLAN AND CO., LIMITED Technological Change and Economic LONDON a BOMBAY a CALCUTTA MADRAS a MELBOURNE Development from 1800 to 1947 THE MACMILLAN COMPANY OF CANADA, LIMITED TORONTO By ARTHUR A. BRIGHT, Jr. THE MACMILLAN COMPANY • NEW YORK 1949 FOREWORD THIS study of the economic development of the electric- lamp industry is the second volume in a series of studies on the economics of innovation, undertaken at the Massachusetts Insti- tute of Technology. The creative role played by science and technology in modern economic life is apparent to everyone. But we know relatively little about the human factors which condition the introduction of technological change into our environment. Are there barriers to innovation inherent in the increasing concentration of power in a few large concerns? Does the patent system, designed as an incentive to invention, act more often as a brake on new develop- ments? What has been the role of key personalities in creating change? Are there lessons to be drawn from the past on how the innovating process can be more effective, not only from the standpoint of achieving a higher standard of material being but from the point of view of smoother human relations? Certainly, material progress at any price is not a satisfactory goal. On the other hand, freedom for creative action in initiating and carrying out new developments is a basic human drive for many individu- als. I believe, personally, that a great society should strive toward a goal which will give to individuals and groups the maximum opportunities for creative expression; yet this means to me that the State must act to prevent the compulsive pressure of some particular group from overriding others to the destruction of human values. -

Biofluorescence

Things That Glow In The Dark Classroom Activities That Explore Spectra and Fluorescence Linda Shore [email protected] “Hot Topics: Research Revelations from the Biotech Revolution” Saturday, April 19, 2008 Caltech-Exploratorium Learning Lab (CELL) Workshop Special Guest: Dr. Rusty Lansford, Senior Scientist and Instructor, Caltech Contents Exploring Spectra – Using a spectrascope to examine many different kinds of common continuous, emission, and absorption spectra. Luminescence – A complete description of many different examples of luminescence in the natural and engineered world. Exploratorium Teacher Institute Page 1 © 2008 Exploratorium, all rights reserved Exploring Spectra (by Paul Doherty and Linda Shore) Using a spectrometer The project Star spectrometer can be used to look at the spectra of many different sources. It is available from Learning Technologies, for under $20. Learning Technologies, Inc., 59 Walden St., Cambridge, MA 02140 You can also build your own spectroscope. http://www.exo.net/~pauld/activities/CDspectrometer/cdspectrometer.html Incandescent light An incandescent light has a continuous spectrum with all visible colors present. There are no bright lines and no dark lines in the spectrum. This is one of the most important spectra, a blackbody spectrum emitted by a hot object. The blackbody spectrum is a function of temperature, cooler objects emit redder light, hotter objects white or even bluish light. Fluorescent light The spectrum of a fluorescent light has bright lines and a continuous spectrum. The bright lines come from mercury gas inside the tube while the continuous spectrum comes from the phosphor coating lining the interior of the tube. Exploratorium Teacher Institute Page 2 © 2008 Exploratorium, all rights reserved CLF Light There is a new kind of fluorescent called a CFL (compact fluorescent lamp). -

Photons Outline

1 Photons Observational Astronomy 2019 Part 1 Prof. S.C. Trager 2 Outline Wavelengths, frequencies, and energies of photons The EM spectrum Fluxes, filters, magnitudes & colors 3 Wavelengths, frequencies, and energies of photons Recall that λν=c, where λ is the wavelength of a photon, ν is its frequency, and c is the speed of light in a vacuum, c=2.997925×1010 cm s–1 The human eye is sensitive to wavelengths from ~3900 Å (1 Å=0.1 nm=10–8 cm=10–10 m) – blue light – to ~7200 Å – red light 4 “Optical” astronomy runs from ~3100 Å (the atmospheric cutoff) to ~1 µm (=1000 nm=10000 Å) Optical astronomers often refer to λ>8000 Å as “near- infrared” (NIR) – because it’s beyond the wavelength sensitivity of most people’s eyes – although NIR typically refers to the wavelength range ~1 µm to ~2.5 µm We’ll come back to this in a minute! 5 The energy of a photon is E=hν, where h=6.626×10–27 erg s is Planck’s constant High-energy (extreme UV, X-ray, γ-ray) astronomers often use eV (electron volt) as an energy unit, where 1 eV=1.602176×10–12 erg 6 Some useful relations: E (erg) 14 ⌫ (Hz) = 1 =2.418 10 E (eV) h (erg s− ) ⇥ ⇥ c hc 1 1 1 λ (A)˚ = = = 12398.4 E− (eV− ) ⌫ ⌫ E (eV) ⇥ Therefore a photon with a wavelength of 10 Å has an energy of ≈1.24 keV 7 If a photon was emitted from a blackbody of temperature T, then the average photon energy is Eav~kT, where k = 1.381×10–16 erg K–1 = 8.617×10–5 eV K–1 is Boltzmann’s constant.