Impacts of Cross-Carriage Measure On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Operating and Financial Review

OPERATING AND FINANCIAL REVIEW > The SingTel Group is Asia’s leading communications group. We provide a wide spectrum of multimedia and ICT solutions, including voice, data and video services over fixed and wireless platforms. The Group is structured along three key businesses: Group Consumer, Group Digital L!fe and Group ICT. Our main operations are in Singapore and Australia. In Singapore, SingTel has more than 130 years of operating experience and played an integral part in the country’s development as a major communications hub. We continue to lead and shape the digital consumer market and the enterprise ICT market. Optus is an Australian leader in integrated telecommunications, driving competition and delivering innovative products and services to customers. We are a major player in Asia and Africa through our strategic investments in six regional mobile operators. The Group’s investments are in AIS (Thailand), Globe (the Philippines), PBTL (Bangladesh), Telkomsel (Indonesia) and Warid (Pakistan). We also have investments in Airtel (India), which has significant presence in Africa and South Asia. We are a long-term strategic investor and work closely with our associates to grow the business, by leveraging our scale in networks, customer reach and extensive operational experience. Together, the Group serves 445 million mobile customers as at 31 March 2012. In this section, we provide a strategic review of the SingTel Group’s operations and discuss the financial performance of the Group for the financial year ended 31 March 2012. CONTENTS -

Hu B B Ing. a C Hieving E Ven More S Tarhu B L Td a N Nual Report 2 0 11

Hubbing. More Achieving Even StarHub Ltd Reg. No: 199802208C Annual Report Ltd StarHub 2011 67 Ubi Avenue 1 #05-01 StarHub Green Singapore 408942 Tel: (65) 6825 5000 Fax: (65) 6721 5000 www.starhub.com 2011 PORT ANNUAL RE For the fi rst time, a detailed Content > 1 CORPORATE INFORMATION sustainability report has been Our Key Figures for the Year prepared in accordance with > 2 Our Financial Highlights the Global Reporting Initiative Board of Directors Nominating Committee Auditors > 4 TAN Guong Ching (Chairman) Peter SEAH Lim Huat (Chairman) KPMG LLP Chairman’s Message (GRI) G3.1 guidelines, including Neil MONTEFIORE (CEO) LEE Theng Kiat Certifi ed Public Accountants GRI’s Telecommunications > 8 KUA Hong Pak TEO Ek Tor 16 Raffl es Quay #22-00 Message from the CEO Peter SEAH Lim Huat Hong Leong Building Nihal Vijaya Devadas KAVIRATNE CBE Strategy Committee Singapore 048581 Sector Supplement. Social and > 12 LEE Theng Kiat Nihal Vijaya Devadas KAVIRATNE CBE Partner-in-charge: ANG Fung Fung Even More Enhanced environmental data presented Steven Terrell CLONTZ (Chairman) (appointed w.e.f. 1 January 2011) > 16 LIM Ming Seong TAN Guong Ching in this report establishes Even More Engaging Sadao MAKI Steven Terrell CLONTZ Subsidiaries TEO Ek Tor LIM Ming Seong StarHub Mobile Pte Ltd > 18 our baseline. StarHub is LIU Chee Ming LIU Chee Ming Even More Enthralling StarHub Cable Vision Ltd. Robert J. SACHS Robert J. SACHS StarHub Internet Pte Ltd committed to working toward > 20 Nasser MARAFIH Stephen Geoffrey MILLER StarHub Online Pte Ltd setting targets and goals for Even More Endearing SIO Tat Hiang YONG Lum Sung SHINE Systems Assets Pte. -

Intergenerational Interaction; Prime-Time Television; Taiwan

Lien, S-C, Zhang, Y.B., & Hummert, M. L. (2009). Older adults in prime-time television in Taiwan: Prevalence, portrayal, and communication interaction. Journal of Cross Cultural Gerontology, 24, 355-372. Publisher’s official version: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10823-009-9100-3, Open Access version: http://kuscholarworks.ku.edu/dspace/. [This document contains the author’s accepted manuscript. For the publisher’s version, see the link in the header of this document.] Paper citation: Lien, S-C, Zhang, Y.B., & Hummert, M. L. (2009). Older adults in prime-time television in Taiwan: Prevalence, portrayal, and communication interaction. Journal of Cross Cultural Gerontology, 24, 355- 372. Abstract: A content and thematic analysis of 109 episodes (94.9 hours) of prime-time dramas examined the portrayals of aging and the nature of intergenerational interaction involving older adults on Taiwanese television. The content analysis revealed that older characters, regardless of sex, appeared less frequently and in less prominent roles than other adult characters, but not in comparison to adolescents and children. The older characters who did appear, however, were predominantly portrayed as cognitively sound and physically healthy. The thematic analysis provided a different picture, showing that older characters talked about age explicitly, strategically linking it to death and despondence, to influence younger characters. Communication behavior themes identified included supporting, superiority, and controlling for older characters, and reverence/respect for younger characters. Findings are compared to those from similar studies of U.S. media and discussed from a Cultivation Theory perspective in terms of their reinforcement of Chinese age stereotypes and the traditional values of filial piety and age hierarchy in the context of globalization and culture change. -

Report for the Advisory Committee for Chinese Programmes 2010/2012 华文节目咨询委员会 : 2010/2012 汇报

REPORT FOR THE ADVISORY COMMITTEE FOR CHINESE PROGRAMMES 2010/2012 华文节目咨询委员会 : 2010/2012 汇报 ACCESS REPORT 2010/2012 CONTENT (I) Introduction Page 3 a. Background b. The Committee’s Work (II) Summary of Key Recommendations Page 4 (III) Observation and Recommendations on the Range and Quality Page 5 of Chinese Programmes a. News, Current Affairs, Cultural and Info-Educational Programmes b. Dramas c. Variety and Entertainment Programmes d. Children and Youth Programmes e. Programmes for the Elderly f. Radio Programmes (IV) Other Programming Concerns Page 9 a. New Rating and logos on TV b. Use of New Media Tools (V) Conclusion Page 10 Annex A: List of Members Page 11 Annex B: Broadcasters’ Responses to the Report Page 13 (I) INTRODUCTION 2 ACCESS REPORT 2010/2012 (I) INTRODUCTION a) Background 1 The Advisory Committee for Chinese Programmes (ACCESS) (华文节目咨询委员会) was first set up in 1994 to advise and give feedback on the range and quality of Chinese programmes on the Free-to-Air TV channels and radio stations with the aim to enhance the broadcasters’ role to entertain, inform and educate viewers. The Committee also advises on Chinese programmes on Pay TV. 2 This report by ACCESS covers the period of 1 July 2010 to 30 June 2012. The current Committee was appointed by the Minister for Information, Communication and the Arts (MICA) for a two-year term with effect from 1 July 2010. The list of Committee members can be found in Annex A . b) The Committee’s Work 3 The Committee undertook the following: a) Reviewed and gave feedback on Chinese programming on MediaCorp’s Channel 8 and Channel U, Pay TV channels, and radio stations; b) Reviewed and provided recommendations on the range and quality of Chinese programmes; c) Reviewed and provided feedback on censorship issues, including those arising from public complaints; and d) Provided support and advice to the Media Development Authority (MDA) in the formulation of content guidelines and public education. -

C NTENTASIA Data • Buyers •

programming • schedules • C NTENTASIA data • buyers • www.contentasia.tv Issue 124: 18-31 July 2011 what’sinside 100% success for new S’pore rule My 360º Life Exclusive deals vanish in face of cross-carriage Romain Oudart, TV5 Monde Singapore’s official efforts to StarHub, although the deal is said ContentAsia’s regular 2011 steer the pay-TV market away to have been done. section asks media execs what from exclusive carriage con- The pressure to up its game downtherabbithole differences the latest gadgets, tracts appears to have been is now on telco SingTel, widely tablets, applications & other 100% successful. believed to have been a driving tech wonders are making to Not a single exclusive carriage force for a new environment. their lives and thoughts. What’s really going on deal has been signed since 12 SingTel added three channels page 10 out there... March 2010 – the date media to its Mio TV line up this month authorities set as the dividing (see p4) but is yet to add any INproduction “Some things have line between old and new car- new mega-players, like FIC. Oth- Scrawl Studios changed about our world... riage regimes. Existing deals ers, such as Discovery and HBO, A who’s who of production We want to weigh all of that on that date are unaffected. remain exclusive to StarHub as houses across Asia Pacific. into our [Australia Network] Channels with new exclusive their agreements pre-date March page 12 tender process,” Australian PM agreements have to offer them 2010. BPL and ESPN Star Sports are Julia Gillard was quoted by The to rival carriers from 1 August exclusive to SingTel Mio. -

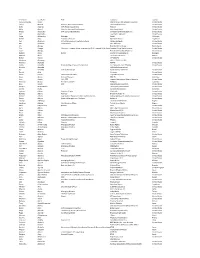

Downlinkin/ Uplinking Only Language Date of Permission 1 9X 9X ME

Master List of Permitted Private Satellite TV Channels as on 31.07.2018 Sr. No. Channel Name Name of the Company Category Upliniking/ Language Date of Downlinkin/ Permission Uplinking Only 1 9X 9X MEDIA PRIVATE LIMITED NON-NEWS UPLINKING & HINDI 24-09-2007 DOWNLINKING 2 9XM 9X MEDIA PRIVATE LIMITED NON-NEWS HINDI/ENGLISHUPLINKING & /BENGALI&ALL INDIAN INDIAN SCHEDULE 24-09-2007LANGUAGE DOWNLINKING 3 9XO (9XM VELVET) 9X MEDIA PRIVATE LIMITED NON-NEWS UPLINKING & HINDI 29-09-2011 DOWNLINKING 4 9X JHAKAAS (9X MARATHI) 9X MEDIA PRIVATE LIMITED NON-NEWS UPLINKING & MARATHI 29-09-2011 DOWNLINKING 5 9X JALWA (PHIR SE 9X) 9X MEDIA PRIVATE LIMITED NON-NEWS UPLINKING & HINDI/ENGLISH /BENGALI&ALL 29-09-2011 DOWNLINKING INDIAN INDIAN SCHEDULE LANGUAGE 6 Housefull Action (earlier 9X BAJAO 9X MEDIA PVT. LTD. NON-NEWS UPLINKING & HINDI 17-01-2015 (Earlier 9X BAJAAO & 9X BANGLA) DOWNLINKING 7 TV 24 A ONE NEWS TIME BROADCASTING NEWS UPLINKING & HINDI/ PUNJABI/ ENGLISH 21-10-2008 PRIVATE LIMITED DOWNLINKING 8 BHASKAR NEWS (AP 9) A.R. RAIL VIKAS SERVICES PVT. LTD. NEWS UPLINKING & HINDI, ENGLISH, MARATHI AND ALL 14-10-2011 DOWNLINKING OTHER INDIAN SCHEDULE LANGUAGE 9 SATYA A.R. RAIL VIKAS SERVICES PVT. LTD. NON-NEWS UPLINKING & HINDI, ENGLISH, MARATHI AND ALL 14-10-2011 DOWNLINKING OTHER INDIAN SCHEDULE LANGUAGE 10 Shiva Shakthi Sai TV (earlier BENZE AADRI ENTERTAINMENT AND MEDIA NON-NEWS UPLINKING & TELUGU/HINDI/ENGLISH/GUJARATI/T 22-11-2011 TV (Earlier AADRI ENRICH) WORKS PVT.LTD. DOWNLINKING AMIL/KANNADA/BENGALI/MALAYALA M 11 Mahua Plus (earlier AGRO ROYAL TV AADRI ENTERTAINMENT AND MEDIA NON-NEWS UPLINKING & TELUGU/HINDI/ENGLISH/GUJARATI/T 22-11-2011 (Earlier AADRI WELLNESS) WORKS PVT.LTD. -

First Name Last Name Title Company Country Anouk Florencia Aaron Warner Bros

First Name Last Name Title Company Country Anouk Florencia Aaron Warner Bros. International Television United States Carlos Abascal Director, Ole Communications Ole Communications United States Kelly Abcarian SVP, Product Leadership Nielsen United States Mike Abend Director, Business Development New Form Digital United States Friday Abernethy SVP, Content Distribution Univision Communications Inc United States Jack Abernethy Twentieth Television United States Salua Abisambra Manager Salabi Colombia Rafael Aboy Account Executive Newsline Report Argentina Cori Abraham SVP of Development and International Oxygen Network United States Mo Abraham Camera Man VIP Television United States Cris Abrego Endemol Shine Group Netherlands Cris Abrego Chairman, Endemol Shine Americas and CEO, Endemol Shine North EndemolAmerica Shine North America United States Steve Abrego Endemol Shine North America United States Patrícia Abreu Dirctor Upstar Comunicações SA Portugal Manuel Abud TV Azteca SAB de CV Mexico Rafael Abudo VIP 2000 TV United States Abraham Aburman LIVE IT PRODUCTIONS Francine Acevedo NATPE United States Hulda Acevedo Programming Acquisitions Executive A+E Networks Latin America United States Kristine Acevedo All3Media International Ric Acevedo Executive Producer North Atlantic Media LLC United States Ronald Acha Univision United States David Acosta Senior Vice President City National Bank United States Jorge Acosta General Manager NTC TV Colombia Juan Acosta EVP, COO Viacom International Media Networks United States Mauricio Acosta President and CEO MAZDOC Colombia Raul Acosta CEO Global Media Federation United States Viviana Acosta-Rubio Telemundo Internacional United States Camilo Acuña Caracol Internacional Colombia Andrea Adams Director of Sales FilmTrack United States Barbara Adams Founder Broken To Reign TV United States Robin C. Adams Executive In Charge of Content and Production Endavo Media and Communications, Inc. -

Master List of Permitted Private Satellite TV Channels As on 31.12.2017 Sr

Master List of Permitted Private Satellite TV Channels as on 31.12.2017 Sr. No. Channel Name Name of the Company Category Upliniking/ Language Date of Downlinkin/ Permission Uplinking Only 1 9X 9X MEDIA PRIVATE LIMITED NON-NEWS UPLINKING HINDI 24-09-2007 2 9XM 9X MEDIA PRIVATE LIMITED NON-NEWS UPLINKING HINDI/ENGLISH /BENGALI&ALL 24-09-2007 3 9XO (9XM VELVET) 9X MEDIA PRIVATE LIMITED NON-NEWS UPLINKING HINDIINDIAN INDIAN SCHEDULE 29-09-2011 4 9X JHAKAAS (9X MARATHI) 9X MEDIA PRIVATE LIMITED NON-NEWS UPLINKING MARATHI 29-09-2011 5 9X JALWA (PHIR SE 9X) 9X MEDIA PRIVATE LIMITED NON-NEWS UPLINKING HINDI/ENGLISH /BENGALI&ALL 29-09-2011 6 Housefull Action (earlier 9X BAJAO 9X MEDIA PVT. LTD. NON-NEWS UPLINKING HINDIINDIAN INDIAN SCHEDULE 17/01/2015 (Earlier 9X BAJAAO & 9X BANGLA) 7 TV 24 A ONE NEWS TIME BROADCASTING NEWS UPLINKING HINDI/ PUNJABI/ ENGLISH 21/10/2008 PRIVATE LIMITED 8 BHASKAR NEWS (AP 9) A.R. RAIL VIKAS SERVICES PVT. LTD. NEWS UPLINKING HINDI, ENGLISH, MARATHI AND ALL 14-10-2011 OTHER INDIAN SCHEDULE LANGUAGE 9 SATYA A.R. RAIL VIKAS SERVICES PVT. LTD. NON-NEWS UPLINKING HINDI, ENGLISH, MARATHI AND ALL 14-10-2011 OTHER INDIAN SCHEDULE LANGUAGE 10 Shiva Shakthi Sai TV (earlier BENZE AADRI ENTERTAINMENT AND MEDIA NON-NEWS UPLINKING TELUGU/HINDI/ENGLISH/GUJARATI/T 22-11-2011 TV (Earlier AADRI ENRICH) WORKS PVT.LTD. AMIL/KANNADA/BENGALI/MALAYALA M 11 Mahua Plus (earlier AGRO ROYAL TV AADRI ENTERTAINMENT AND MEDIA NON-NEWS UPLINKING TELUGU/HINDI/ENGLISH/GUJARATI/T 22-11-2011 (Earlier AADRI WELLNESS) WORKS PVT.LTD. -

PDF ATF Dec12

> 2 < PRENSARIO INTERNATIONAL Commentary THE NEW DIMENSIONS OF ASIA We are really pleased about this ATF issue of world with the dynamics they have for Asian local Prensario, as this is the first time we include so projects. More collaboration deals, co-productions many (and so interesting) local reports and main and win-win business relationships are needed, with broadcaster interviews to show the new stages that companies from the West… buying and selling. With content business is taking in Asia. Our feedback in this, plus the strength and the capabilities of the the region is going upper and upper, and we are region, the future will be brilliant for sure. pleased about that, too. Please read (if you can) our central report. There THE BASICS you have new and different twists of business devel- For those reading Prensario International opments in Asia, within the region and below the for the first time… we are a print publication with interaction with the world. We stress that Asia is more than 20 years in the media industry, covering Prensario today one of the best regions of the world to proceed the whole international market. We’ve been focused International with content business today, considering the size of on Asian matters for at least 15 years, and we’ve been ©2012 EDITORIAL PRENSARIO SRL PAYMENTS TO THE ORDER OF the market and the vanguard media ventures we see attending ATF in Singapore for the last 5 years. EDITORIAL PRENSARIO SRL in its main territories; the problems of the U.S. and As well, we’ve strongly developed our online OR BY CREDIT CARD. -

Information Circular to the Pay Tv Industry in Respect

INFORMATION CIRCULAR TO THE PAY TV INDUSTRY IN RESPECT OF IMDA’S DECISION ON EXEMPTION FROM OBLIGATIONS UNDER PARAGRAPH 2.7 OF THE MEDIA MARKET CONDUCT CODE (“CODE”) IN RELATION TO FREE PREVIEW OF PREMIER LEAGUE (“PL”) CONTENT 4 August 2017 1. In July 2017, IMDA granted SingNet Pte Ltd (“SingNet”) an exemption from its obligations under Paragraph 2.7 of the Media Market Conduct Code (“Code”) to cross-carry the offering of free preview of PL content to consumer and corporate subscribers on the Singtel TV platform from 4 August 2017 to 14 August 2017 (“National Day PL Free Preview”). This industry circular sets out IMDA’s considerations in relation to the above. IMDA’s considerations 2. In assessing SingNet’s exemption application to offer the National Day PL Free Preview, IMDA considered that: (a) SingNet has not been regularly offering the PL content as a free preview on the Singtel TV platform only, and the National Day PL Free Preview is proposed to be offered on a one-off basis for a short period from 4 to 14 August 2017, with the broadcast of 10 “live” matches only; (b) SingNet will be opening up all Singtel TV channelsi for free preview on the Singtel TV platform during the same period; (c) the free preview of all Singtel TV channels is accessible by all Singtel TV subscribers on the Singtel TV platform; and (d) free previews of all channels will provide customers with an opportunity to review the content and make an informed decision as to whether to subscribe to packages that include the PL content. -

Commission of the European Communities

COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES ENGLISH VERSION ONLY COM(94) 183 final -Volume I I Brussels, 21.06.1994 MID-TERM REVIE\V OF THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE COMMUNITY PROGRAMME- ESTABLISHMENT OF AN INTERNAL INFORMATION SERVICES MARKET (1991 -1995) IMPACT 2 Evaluation Report dra~vn up by Independent Experts IMPACT II MID-TERM EVALUATION; FOR AN INFORMATION STRATEGY by Rene Mayer, Chairman Arnoud de Kemp, Roberto Liscia, John Martyn, Joao Campos Rodrigues, Experts, Mogens Rasmussen, Rapporteur Report drawn up at the request of the Commission ofthe European Communities DGXIIIIE - 1 - CONTENTS Chapter I. A MUCH REDUCED PROGRAMME 7 II. IN A FAST MOVING WORLD 37 III. THE ESSENTIALS OF A EUROPEAN STRATEGY 57 IV. CONCLUSION AND PROPOSALS 73 ANNEXES 1. THE EUROPEAN INFORMATION RESOURCE 79 2. ACTION LINES 1, 2 and 4 81 3. THE IMPACT 2 AND LFR's 93 5. NEXT STEPS FOR IMPACT 2 123 -3- First ofall, the authors wish to give special thanks to the officials ofDG XJIIIE who, with a keen sense of their responsibilities, provided intelligent and effective assistance throughout the drafting ofthe report. They demonstrated a perfect grasp of the aims of the task in hand, answered all our questions, provided extensive documentation and showed boundless patience. The authors are also greatly indebted to the work of their predecessors on the panel which, three years previously, was responsible for assessing IMPACT I -5- This report has been drawn up in accordance with Article 6 of the Council Decision of 12 December 1991, which states that "at mid-term,( ... ) an evaluation report (shall be) drawn up by independent experts on the results obtained in implementing the action lines" constituting the IMP ACT II programme. -

The Philippines Are a Chain of More Than 7,000 Tropical Islands with a Fast Growing Economy, an Educated Population and a Strong Attachment to Democracy

1 Philippines Media and telecoms landscape guide August 2012 1 2 Index Page Introduction..................................................................................................... 3 Media overview................................................................................................13 Radio overview................................................................................................22 Radio networks..........……………………..........................................................32 List of radio stations by province................……………………………………42 List of internet radio stations........................................................................138 Television overview........................................................................................141 Television networks………………………………………………………………..149 List of TV stations by region..........................................................................155 Print overview..................................................................................................168 Newspapers………………………………………………………………………….174 News agencies.................................................................................................183 Online media…….............................................................................................188 Traditional and informal channels of communication.................................193 Media resources..............................................................................................195 Telecoms overview.........................................................................................209