Gregory Sholette

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Culture Jamming

Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank Vincent de Jong for introducing me to the intricacy of the easyCity action, and for taking the time to answer my questions along my exploration of the case. I also want to thank Robin van t’ Haar for his surprising, and unique, contribution to my investigations of the easyCity action. Rozalinda Borcila, the insights you have shared with me have been a crucial reminder of my own privilieged position – your reflections, I hope, also became a marker in what I have written. Also, I would like to thank others that somehow made my fieldwork possible, and influenced my ‘learning’ of activism and culture jamming. Of these I would especially like to thank Nina Haukeland for introducing me to the politics of activism, Kirsti Hyldmo for reminding me of the realities of exploitation, Åse Brandvold for a skilled introduction to the thoughts and tools of culture jamming, and Maria Astrup for showing me the pleasures and powers of aesthetics. Also, I would like to thank the Norwegian Adbusters Network, and the editorial groups of Vreng. To my main advisor Professor Kristian Stokke, I would like to thank you for the excellent support you have given me throughout my master studies. Your insights have been of grate value, and I cannot thank you enough for continually challenging me. Also, the feedback from Olve Krange, my second advisor, was crucial at the early stage of developing the thesis, to defining its object of inquiry, and finally when writing my conclusion. I would also like to express my appreciation to Professor Oddrun Sæther for an excellent introduction to the field of cultural studies, to Professor Matt Sparke at the University of Washington for demonstrating the intriguing complexities of political geography, and to PhD candidate Stephen Young, for proof reading and fruitful inputs at the final stage of writing. -

Re:Imagining Change

WHERE IMAGINATION BUILDS POWER RE:IMAGINING CHANGE How to use story-based strategy to win campaigns, build movements, and change the world by Patrick Reinsborough & Doyle Canning 1ST EDITION Advance Praise for Re:Imagining Change “Re:Imagining Change is a one-of-a-kind essential resource for everyone who is thinking big, challenging the powers-that-be and working hard to make a better world from the ground up. is innovative book provides the tools, analysis, and inspiration to help activists everywhere be more effective, creative and strategic. is handbook is like rocket fuel for your social change imagination.” ~Antonia Juhasz, author of e Tyranny of Oil: e World’s Most Powerful Industry and What We Must Do To Stop It and e Bush Agenda: Invading the World, One Economy at a Time “We are surrounded and shaped by stories every day—sometimes for bet- ter, sometimes for worse. But what Doyle Canning and Patrick Reinsbor- ough point out is a beautiful and powerful truth: that we are all storytellers too. Armed with the right narrative tools, activists can not only open the world’s eyes to injustice, but feed the desire for a better world. Re:Imagining Change is a powerful weapon for a more democratic, creative and hopeful future.” ~Raj Patel, author of Stuffed & Starved and e Value of Nothing: How to Reshape Market Society and Redefine Democracy “Yo Organizers! Stop what you are doing for a couple hours and soak up this book! We know the importance of smart “issue framing.” But Re:Imagining Change will move our organizing further as we connect to the powerful narrative stories and memes of our culture.” ~ Chuck Collins, Institute for Policy Studies, author of e Economic Meltdown Funnies and other books on economic inequality “Politics is as much about who controls meanings as it is about who holds public office and sits in office suites. -

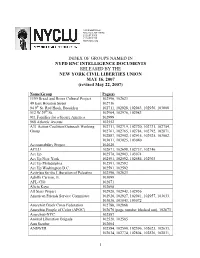

Index of Political Groups Mentioned in the Intelligence Documents

125 Broad Street New York, NY 10004 212.607.3300 212.607.3318 www.nyclu.org INDEX OF GROUPS NAMED IN NYPD RNC INTELLIGENCE DOCUMENTS RELEASED BY THE NEW YORK CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION MAY 16, 2007 (revised May 22, 2007) Name/Group Page(s) 1199 Bread and Roses Cultural Project 102596, 102623 49 East Houston Street 102716 94 9th St. Red Hook, Brooklyn 102711, 102928, 102943, 102956, 103008 512 W 29th St. 102964, 102976, 102983 911 Families for a Secure America 102999 968 Atlantic Avenue 102552 A31 Action Coalition/Outreach Working 102711, 102719, 102720, 102731, 102754, Group 102761, 102765, 102784, 102792, 102871, 102887, 102902, 102915, 102925, 103002, 103011, 103025, 103040 Accountability Project 102620 ACLU 102671, 102698, 102737, 102746 Act Up 102578, 102903, 103074 Act Up New York 102591, 102592, 102684, 102903 Act Up Philadelphia 102591, 102592 Act Up Washington D.C. 102591, 102592 Activists for the Liberation of Palestine 102596, 102623 Adolfo Carrion, Jr. 103099 AFL-CIO 102671 Alicia Keys 102698 All Stars Project 102928, 102943, 102956 American Friends Service Committee 102920, 102927, 102941, 102957, 103033, 103036, 103043, 103072 Anarchist Black Cross Federation 102788, 102868 Anarchist People of Color (APOC) 102670 (page number blacked out), 102673 Anarchist-NYC 102587 Animal Liberation Brigade 102520, 102585 Ann Stauber 102604 ANSWER 102584, 102590, 102596, 102623, 102633, 102634, 102774, 102804, 102826, 102831, 1 102843, 102884, 102900, 102906, 102916, 102919, 102926, 102940, 102952, 102959, 103068, 103076, 103092, 103096 Anthony -

Dead Kennedys and the Yippie-Punk Continuum I Michael Stewart Foley

Political Pie-Throwing: Dead Kennedys and the Yippie-Punk Continuum i Michael Stewart Foley To cite this version: Michael Stewart Foley. Political Pie-Throwing: Dead Kennedys and the Yippie-Punk Continuum i. Sonic Politics: Music and Social Movements in the Americas, 2019, 1138389390. hal-01999010 HAL Id: hal-01999010 https://hal.univ-grenoble-alpes.fr/hal-01999010 Submitted on 30 Jan 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Political Pie-Throwing: Dead Kennedys and the Yippie-Punk Continuumi MICHAEL STEWART FOLEY By the time Dead Kennedys released their first LP, Fresh Fruit for Rotting Vegetables, in 1980, the band had established itself as the leading American political punk band, hailing from a city that seemed to specialize in political art. In many ways, the band and its music represented the culmination of nearly three years of subcultural political struggle on a host of issues facing not only young people in San Francisco but American youth everywhere – enough that, to this day, many of the city’s punk veterans refer to their experience in the “movement.” Political historians of the United States in the 1970s and 1980s have mostly ignored punk, but this essay examines Dead Kennedys’ early career as a way to illuminate the political experience of one segment of American youth in the late 1970s. -

Corporate Holiday Parties Are Back Print It! Catalogs Still Sell

MARTHA GRAHAM’S BALANCING ACT Dance co. seeks board chair, donors CRAIN’S® NEW YORK BUSINESS PAGE 4 getty images VOL. XXIX, NO. 47 WWW.CRAINSNEWYORK.COM NOVEMBER 25-DECEMBER 1, 2013 PRICE: $3.00 Corporate holiday parties are back Best year since 1990s. Don’t order bubbly just yet—the house wine will have to do BY LISA FICKENSCHER Corporate bean counters slashed holi- day parties at posh venues like the Waldorf Astoria during the economic downturn, choosing less ostentatious spots or forgoing festivities altogether. But next month, the luxury property’s regal ballrooms will be overflowing with celebrations. “This year is the first year since 2007 that we’ve seen a significant change in interest and demand—de- mand we can’t even accommodate,” said James Blauvelt, executive director of catering for the hotel. “We haven’t been at the front of the roster for these Lot owners: parties for several years, because if you See PARTIES on Page 27 Put up or pay up Print it! buck ennis De Blasio bid to close tax loophole could force landlords to build Catalogs new housing on their vacant plots or sell out to those who will still sell And yet, because most of the proper- more than 10,500 lots in the five bor- BY JOE ANUTA $6.8K ty is zoned for residential use, and is as- oughs, with the largest concentration on PROPERTY sessed in the same low-density class as Staten Island. The plan, after a five-year Even e-commerce Call it Exhibit A. On part of an irregu- TAXES paid single-family homes, the Olnick Orga- phase-in period, would hike yearly rates annually by Frank brands jump on larly shaped block in the Highbridge sec- Fristachi and nization, which owns the land, pays less by an average of $15,300, according to tion of the Bronx, a chain-link fence Suzannah than $8,000 annually in property taxes on estimates by the Independent Budget the paper sales pitch wraps around a three-acre property that Matalon on their that residential portion. -

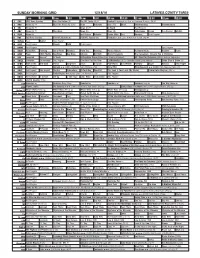

Sunday Morning Grid 12/18/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/18/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Pittsburgh Steelers at Cincinnati Bengals. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) News Naturally Give (TVY) Heart Snowboarding Snowboarding 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Jack Hanna Ocean Sea Rescue Wildlife 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Paid Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Detroit Lions at New York Giants. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Alsace-Hubert Heirloom Meals Healthy Kevin 28 KCET Peep 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Mario Frangoulis The Carpenters: Close to You & Christmas 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch A Christmas Truce (2015) Craig Olejnik, Ali Liebert. All I Want for Christmas (2013) Melissa Sagemiller. 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Grandma Got Run Over La Madrecita (1973, Comedia) María Elena Velasco. Como Dice el Dicho (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Jumanji ›› (1995, Fantasía) Robin Williams. -

Framing Comedies of Recognition and Repertoires of Tactical Frivolity Within Social Movements A.T

Interface: a journal for and about social movements Article Volume 8 (2): pp. 286 - 310 (November 2016) Kingsmith, Why so serious? Why so serious? Framing comedies of recognition and repertoires of tactical frivolity within social movements A.T. Kingsmith Abstract What makes something funny? That depends. When it comes to humour, we are all experts. We know what we find funny. Such ambiguity is one of the central reasons a phenomenological analysis of humour as a means for radical political subject formations has been neglected within the study of social movements. Yet in many contexts a joke can represent liberation from pressure, rebellion against authority, a subversive political performance. We might even say that given common social norms and linguistic signifiers, joke telling can tear holes in our usual predictions about the empirical world by creating disjunctions between actuality and representation. After all, those in power have little recourse against mockery. Responding harshly to silence humorous actions tends to in fact increase the laughter. As such, humour must be appreciated not just as comic relief, but as a form of ideological emancipation, a means of deconstructing our social realities, and at the same time, imagining and proposing alternative ones. By informing this notion of humour as subversive political performance with one of the most instrumental approaches to social movement studies, Charles Tilly’s repertoires of contention, this paper begins by framing the dangers of comedic containment, before theorising the creative and electronic turns in social movement studies through a lens of rebellious humour as a post-political act. The paper emphasises these contributions with two unique explorations of political humour: 1970s’ radio frivolity by the post-Marxist Italian Autonomous movement, and present day Internet frivolousness by the hacktivist collective Anonymous. -

Partisans, Nonpartisans, and the Antiwar Movement in the United

American Politics Research Volume 35 Number 4 July 2007 431-464 © 2007 Sage Publications Partisans, Nonpartisans, and 10.1177/1532673X07300763 http://apr.sagepub.com hosted at the Antiwar Movement in http://online.sagepub.com the United States Michael T. Heaney University of Florida Fabio Rojas Indiana University, Bloomington American social movements are often bitterly divided about whether their objectives are achieved better by working with one of the major political par- ties or by operating independently. These divisions are consequential for how social movements and political parties respond to one another. First, differing partisan attitudes shape the structure of activist networks, leading activists to join organizations with others who share their party loyalties or disloyalties. Second, partisan attitudes affect how activists participate in the movement, with strong partisans more likely to embrace institutional tactics, such as lob- bying. Third, partisanship affects activists’ access to the institutions of govern- ment, such as Congress. Relying on surveys of antiwar activists attending large-scale public demonstrations in 2004 and 2005 and a Capitol Hill Lobby Day in September 2005, the authors argue that some activists integrate into major party networks through the “party in the street,” an arena of significant party-movement interaction. Keywords: antiwar movement; social movements; political parties; party in the street; party identification; activist networks; social networks We believe that most of [House Minority Leader Nancy] Pelosi’s constituents perceive her as antiwar because they know only of her initial vote and her later public statements. We believe that we can pressure her by exposing the gap between her rhetoric and her votes and other leadership actions and inactions. -

Invisible Theater P

TACTICS MODES OF ACTION Specific forms of creative action, such as a flash mob or an occupation. “Tactics . lack a specific location, survive through improvi- sation, and use the advantages of the weak against the strong.” —Paul Lewis et al.1 Every discipline has its forms. Soldiers can choose to lay siege or launch a flanking maneuver. Writers can try their hand at biography or flash fiction. Likewise, creative activists have their own repertoire of forms. Some, like the sit-in and the general strike, are justly famous; others, like flash mobs and culture jamming, have a newfangled pop appeal; yet others — like debt strike, prefigurative intervention, eviction blockade — are mostly unknown but could soon make their appearance on the stage of history. If art truly is a hammer with which to shape the world, it’s time to gear up. 1 Paul Lewis, Marc Tsurumaki, and David J. Lewis, Situation normal— (Princeton Architectural Press, 1999). TACTIC: Advanced leaeting COMMON USES Leafleting is the bread-and- “If you’re doing To get important butter of many campaigns. It’s information into the also annoying and ineffective, standard leaeting, right hands. for the most part. How many times have you taken a leaf- you’re wasting PRACTITIONERS let just because you forgot to everybody’s pull your hand back in time, Center for Tactical Magic Institute for Applied only to throw it in the next time. What you Autonomy available trash can? Or you’re need is advanced WAG actually interested and stick it in your pocket, but then you leaeting.” FURTHER INSIGHT never get around to reading Institute for Applied Autonomy, it because it’s a block of tiny, indecipherable text? Well, if “Little Brother” http://www.appliedautonomy.com/lb.html that’s what a committed, world-caring person like you does, just imagine what happens to all the leaflets you give out to Center for Tactical Magic, “The Tactical Ice Cream Unit” harried career-jockeys as they rush to or from work. -

The Contentious Performances of Culture Jamming : Art, Repertoires of Contention, and Social Movement Theory David M

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2013 The contentious performances of culture jamming : art, repertoires of contention, and social movement theory David M. Iles III Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Iles III, David M., "The onc tentious performances of culture jamming : art, repertoires of contention, and social movement theory" (2013). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2812. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2812 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE CONTENTIOUS PERFORMANCES OF CULTURE JAMMING: ART, REPERTOIRES OF CONTENTION, AND SOCIAL MOVEMENT THEORY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Political Science by David M. Iles III B.S., Southeastern Louisiana University, 2006 M.S., Louisiana State University, 2009 December 2013 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation is the culmination of a project first engaged in the Fall of 2007. Either in whole or in part, some of the chapters below are elaborated and refined versions of earlier papers, including Chapters Six and Twelve. My Master’s thesis crystallized many of the questions and approaches of this project. Indeed, the heart of the project (Chapters Two and Three) and its climax (Chapter Twelve) were first forged in the crucible of the thesis. -

The Yes Men and the Utopian Politics of Satirical Fake News

International Journal of Communication 7 (2013), 1243–1264 1932–8036/20130005 From Critique to Mobilization: The Yes Men and the Utopian Politics of Satirical Fake News IAN REILLY Concordia University To date, communication and media scholars have placed significant emphasis on the professionalized forms of satirical fake news currently operating within the structures of corporate media, pointing to their continued efforts to counter the prevailing attitudes and perspectives proliferated across the dominant channels of public discourse. What follows is a broader examination of how politically motivated and activist-oriented practitioners have deployed satirical fake news to call attention to various causes and sites of struggle and to create opportunities for dissenting perspectives to register with broader publics. Satirical fake news has enjoyed considerable success putting forward a broad range of critical perspectives on the mainstream media and on the elites that give shape to the larger discourses of politics and culture. While the range and sophistication of scholarship on the subject has increased considerably in recent years (as evinced by a recent IJoC “Breaking Boundaries” special section), the primary texts under discussion remain those situated within the more instantly recognizable domains of corporate entertainment media. Importantly, satirical fake news has also figured prominently in the articulation of dissent among a wide range of activist practitioners; as I argue in this essay, the appropriation of ironic, parodic, and satirical forms of critique, along with the deployment of emergent mediatory and technological platforms, have facilitated the transmission of dissent for political satirists looking to gain access to broader publics. Indeed, satirical fake news has worked to significantly reframe political discourse on subjects of grave importance to the proper functioning of democracy—from questions regarding the future outcomes of electoral politics to concerns related to the ethical behavior of corporations and governments. -

Exploring Dialogic Social Change

Exploring Dialogic Social Change A dissertation presented to the faculty of the Scripps College of Communication of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Karen P. Greiner June 2010 © 2010 Karen P. Greiner. All Rights Reserved. This dissertation titled Exploring Dialogic Social Change by KAREN P. GREINER has been approved for the School of Communication Studies and the Scripps College of Communication by Devika Chawla Assistant Professor of Communication Studies ________________________________________ Gregory J. Shepherd Professor of Communication Studies Gregory J. Shepherd Dean, Scripps College of Communication ii Abstract GREINER, KAREN P., Ph.D., June 2010, Communication Studies Exploring Dialogic Social Change (259 pp.) Directors of Dissertation: Devika Chawla and Gregory J. Shepherd This dissertation explores a model of social change which I have labeled “dialogic.” Each of the three cases I have chosen for this study has been included because I believe that the design of each intervention departs significantly and creatively from traditional, less Other-oriented, social change efforts. Dialogic social change begins with the assumption that human beings cannot be developed, modernized, or empowered by external parties. Instead, this conception of change is guided by the assumption that individuals are autonomous, trustworthy beings who are capable of deciding when to engage with new ideas and opportunities for action. First, I analyze the strategic communication of the “Billionaires for Bush,” a group of playful and ironic protesters, most active in New York City preceding the 2004 U.S. Presidential election. In this case I focus on the ability of the Billionaires to creatively inspire and invite civic participation, which resulted in the self-organization of more than 70 “spin off” Billionaires for Bush chapters.