Partisans, Nonpartisans, and the Antiwar Movement in the United

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nuclear Resister Issue #145

the Nuclear Resister “A Chronicle of Hope” No. 145 February 18, 2007 8, 12 & 15 Months for Disarming ND’s WMDs Last summer, three men dressed as clowns broke the lock off the fence surround- ing an unguarded nuclear missile launch site in North Dakota, on Fort Berthold Reservation farmland of the Three Affiliated Tribes (Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nations). There they hung a banner declaring “Weapon of Mass Destruction Here”, as well as painting slogans such as “Stop Nuclear Terrorism Here” and hammering and pouring blood on the buried missile silo’s massive reinforced concrete cover. Their action on June 20, 2006 was the latest in the U.S. in the 26-year tradition of the Plowshares nuclear disarmament movement. In that time, hundreds of nonviolent resisters around the world have given flesh to the biblical prophecy of Isaiah and Micah, and begun the work of beating swords into plowshares. Many, if not most, have spent time in prison or jail as a consequence. The “Weapon of Mass Destruction Here” Plowshares defendants were sentenced November 16 in federal court in Bismarck, North Dakota, for destruction of government property. Fr. Carl Kabat OMI was sentenced to 15 months in federal prison, Greg Boertje-Obed was sentenced to 12 months, and Michael Walli received an eight month prison term. The men have been jailed since their arrest at the site, and were given photo by Ted Stein/Resistance Media In black hoods and orange jumpsuits, scores of surrogates for Guantanamo credit for time served in local jails. prisoners kneel and petition the Federal Court in Washington, D.C. -

Revisiting Maternalist Frames Across Cases of Women's Mobilization

WSIF-01856; No of Pages 12 Women's Studies International Forum 51 (2015) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Women's Studies International Forum journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/wsif “Resistance is fertile”1: Revisiting maternalist frames across cases of women’s mobilization Michelle E. Carreon a, Valentine M. Moghadam b a American Studies Program, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, USA b International Affairs Program and Dept. of Sociology, Northeastern University, Boston, MA, USA article info synopsis Available online xxxx Historically, governments and social movements have evoked images of mothers as nurturing, moral, peaceful, or combative agents. But how is a maternalist frame deployed in different contexts? Who deploys this frame, for what purposes and to what ends? In this article, we present a classification scheme to elucidate the diversity and versatility of maternalist frames through the examination of four distinct categories of cases of women's mobilization from the global South as well as North. Drawing on secondary literature and our own ongoing research, we construct a typology of maternalism-from-above and maternalism-from-below to demon- strate how maternalist frames may serve patriarchal or emancipatory purposes with implications for gender justice and the expansion of citizenship rights. © 2015 Published by Elsevier Ltd. In a 1984 photograph, Orlando Valenzuela depicts a smiling appear, and the diverse ways in which maternal identities are Sandinista woman breastfeeding an infant with an AK-47 invoked in political movements and processes, we revisit the strapped to her back. This image – as with previous ones literature and historical record to offer a classification that depicting Vietnamese militant mothers during the U.S. -

Culture Jamming

Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank Vincent de Jong for introducing me to the intricacy of the easyCity action, and for taking the time to answer my questions along my exploration of the case. I also want to thank Robin van t’ Haar for his surprising, and unique, contribution to my investigations of the easyCity action. Rozalinda Borcila, the insights you have shared with me have been a crucial reminder of my own privilieged position – your reflections, I hope, also became a marker in what I have written. Also, I would like to thank others that somehow made my fieldwork possible, and influenced my ‘learning’ of activism and culture jamming. Of these I would especially like to thank Nina Haukeland for introducing me to the politics of activism, Kirsti Hyldmo for reminding me of the realities of exploitation, Åse Brandvold for a skilled introduction to the thoughts and tools of culture jamming, and Maria Astrup for showing me the pleasures and powers of aesthetics. Also, I would like to thank the Norwegian Adbusters Network, and the editorial groups of Vreng. To my main advisor Professor Kristian Stokke, I would like to thank you for the excellent support you have given me throughout my master studies. Your insights have been of grate value, and I cannot thank you enough for continually challenging me. Also, the feedback from Olve Krange, my second advisor, was crucial at the early stage of developing the thesis, to defining its object of inquiry, and finally when writing my conclusion. I would also like to express my appreciation to Professor Oddrun Sæther for an excellent introduction to the field of cultural studies, to Professor Matt Sparke at the University of Washington for demonstrating the intriguing complexities of political geography, and to PhD candidate Stephen Young, for proof reading and fruitful inputs at the final stage of writing. -

Re:Imagining Change

WHERE IMAGINATION BUILDS POWER RE:IMAGINING CHANGE How to use story-based strategy to win campaigns, build movements, and change the world by Patrick Reinsborough & Doyle Canning 1ST EDITION Advance Praise for Re:Imagining Change “Re:Imagining Change is a one-of-a-kind essential resource for everyone who is thinking big, challenging the powers-that-be and working hard to make a better world from the ground up. is innovative book provides the tools, analysis, and inspiration to help activists everywhere be more effective, creative and strategic. is handbook is like rocket fuel for your social change imagination.” ~Antonia Juhasz, author of e Tyranny of Oil: e World’s Most Powerful Industry and What We Must Do To Stop It and e Bush Agenda: Invading the World, One Economy at a Time “We are surrounded and shaped by stories every day—sometimes for bet- ter, sometimes for worse. But what Doyle Canning and Patrick Reinsbor- ough point out is a beautiful and powerful truth: that we are all storytellers too. Armed with the right narrative tools, activists can not only open the world’s eyes to injustice, but feed the desire for a better world. Re:Imagining Change is a powerful weapon for a more democratic, creative and hopeful future.” ~Raj Patel, author of Stuffed & Starved and e Value of Nothing: How to Reshape Market Society and Redefine Democracy “Yo Organizers! Stop what you are doing for a couple hours and soak up this book! We know the importance of smart “issue framing.” But Re:Imagining Change will move our organizing further as we connect to the powerful narrative stories and memes of our culture.” ~ Chuck Collins, Institute for Policy Studies, author of e Economic Meltdown Funnies and other books on economic inequality “Politics is as much about who controls meanings as it is about who holds public office and sits in office suites. -

Winter 2017 Newsletter

Winter 2017-18, volume XXI, issue 4 VETERANS FOR PEACE NEWS MINNEAPOLIS/ST. PAUL VETERANS FOR PEACE, CHAPTER 27 Veterans For Peace News is published quar- Tear down walls, terly by Mpls./St. Paul Veterans For Peace, build up people Chapter 27. by Mary McNellis Veterans For Peace works to increase awareness of the costs his past Armistice Day, of war, restrain our TVeterans for Peace led a government from intervening in the bi-national march on both internal affairs of other sides of the Arizona/Mexican nations, end the arms border at Nogales to shine a race, reduce and even- tually eliminate nuclear light on our new administra- weapons, seek justice tion’s highly politicized “build for veterans and victims of war, and abolish war the wall” and the humanitarian as an instrument of abuses of the U.S. Border national policy. Patrol. Scores of people gath- We pledge to use ered in front of adjacent democratic and non- stages, separated by a 30-foot violent means to fence that “protects” and sepa- achieve our purpose. rates the U.S. from Mexico, to protest a wasteful and inhu- To subscribe to this newsletter, mane policy. please call: It was a weekend filled 612-821-9141 with actions, sponsored by the Or write: School of America Watch Veterans For Peace Ch. 27 (SOAW), founded in 1990 by Father Roy tics resulting in torture, assassinations, kid- 4200 Cedar Ave, S. #7 Bourgeois. This was in response to the Nov. nappings and repression. Labor leaders, union Minneapolis, MN 55407 16, 1989, El Salvador massacre in which six organizers and environmentalists have always Or e-mail: Jesuit priests, their housekeeper and her been among the primary targets of SOA vio- [email protected] teenage daughter were murdered. -

Parish Resources on the Death Penalty

Parish Resources On The Death Penalty Prepared by: Human Rights Commission Diocese of Toledo 2008 3/11/2008 1 Table of Contents Resources for Death Penalty Education in Parishes Introduction of Packet by HRC explaining Packet of Materials 3 Informational Bulletin Fill-Ins 4 Ideas for Use in Initiation, Preaching or Religious Education 7 Prayer Resources 15 Litany for an End to the Death Penalty A Service of Hope: A Prayer Service on the Occasion of an Execution Prayer Vigil for Victims of Gun Violence A Vigil of Witness against Capital Punishment: Signing the Declaration of Life Additional Recommended Resources 30 Books Catholic Resources/Documents Videos Speakers Websites 3/11/2008 2 Greetings of Peace! This packet is intended to provide parishes with a set of resources and tools to educate and inspire our communities to look at how we think about the death penalty and study what the Catholic Church teaches on the issue. In recent years the United States Catholic Conference of Bishops has taken a public stand to end the use of the death penalty. Included in this packet are some basic resources from the Catechism, Encyclicals, our bishops’ statements and the Catholic social tradition. We have put together homily helps, short bulletin inserts, sample prayer services, and additional resources to aid you in reaching out to your parish community. If you have questions or would like additional information, feel free to contact the Diocesan Human Rights Commission through Ms. Germaine Kirk, Diocesan liaison to the Human Rights Commission: 419 – 244-6711, ext. 431 or [email protected]. -

Feminism for the 99 Percent

- ESTO ;:.iii POLITICS / FEMINISM ",,::: $12.95/ £7.99/ $17.50CAN THIS IS Feminism for AMANIFESTO the 99 Percent FOR THE 99 PERCENT Unaffordable housing, poverty wages, inad equate healthcare, border policing, climate change-these are not what you ordinarily hear feminists talking about. But aren't they the biggest issues for the vast majority of women around the globe? Taking as its inspiration the new wave of fem inist militancy that has erupted globally, this manifesto makes a simple but powerful case: feminism shouldn't start-or stop-with the drive to have women represented at the top of their professions. It must focus on those at the bottom, and fight for the world they deserve. And that means targeting capitalism. Feminism must be anticapitalist, eco-socialist and anti racist. Feminism for the 99 Percent A Manifesto Cinzia Arruzza Tithi Bhattacharya Nancy Fraser VERSO London • New York For the Combahee River Collective, who envisioned the path early on and for the Polish and Argentine feminist strikers, who are breaking new ground today First published by Verso 2019 © Cinzia Arruzza, Tithi Bhattacharya, Nancy Fraser 2019 All rights reserved The moral rights of the authors have been asserted 1 3 5 79 10 8 642 Verso UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F OEG US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 10lD, Brooklyn, NY 11201 versobooks.com Verso is the imprint of New Left Books ISBN-13: 978·1-78873-442-4 ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-444-8 (UK EBK) ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-445-5 (US EBK) British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book -

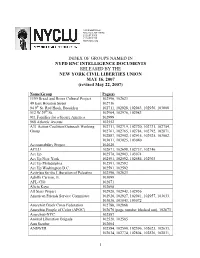

Index of Political Groups Mentioned in the Intelligence Documents

125 Broad Street New York, NY 10004 212.607.3300 212.607.3318 www.nyclu.org INDEX OF GROUPS NAMED IN NYPD RNC INTELLIGENCE DOCUMENTS RELEASED BY THE NEW YORK CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION MAY 16, 2007 (revised May 22, 2007) Name/Group Page(s) 1199 Bread and Roses Cultural Project 102596, 102623 49 East Houston Street 102716 94 9th St. Red Hook, Brooklyn 102711, 102928, 102943, 102956, 103008 512 W 29th St. 102964, 102976, 102983 911 Families for a Secure America 102999 968 Atlantic Avenue 102552 A31 Action Coalition/Outreach Working 102711, 102719, 102720, 102731, 102754, Group 102761, 102765, 102784, 102792, 102871, 102887, 102902, 102915, 102925, 103002, 103011, 103025, 103040 Accountability Project 102620 ACLU 102671, 102698, 102737, 102746 Act Up 102578, 102903, 103074 Act Up New York 102591, 102592, 102684, 102903 Act Up Philadelphia 102591, 102592 Act Up Washington D.C. 102591, 102592 Activists for the Liberation of Palestine 102596, 102623 Adolfo Carrion, Jr. 103099 AFL-CIO 102671 Alicia Keys 102698 All Stars Project 102928, 102943, 102956 American Friends Service Committee 102920, 102927, 102941, 102957, 103033, 103036, 103043, 103072 Anarchist Black Cross Federation 102788, 102868 Anarchist People of Color (APOC) 102670 (page number blacked out), 102673 Anarchist-NYC 102587 Animal Liberation Brigade 102520, 102585 Ann Stauber 102604 ANSWER 102584, 102590, 102596, 102623, 102633, 102634, 102774, 102804, 102826, 102831, 1 102843, 102884, 102900, 102906, 102916, 102919, 102926, 102940, 102952, 102959, 103068, 103076, 103092, 103096 Anthony -

Dead Kennedys and the Yippie-Punk Continuum I Michael Stewart Foley

Political Pie-Throwing: Dead Kennedys and the Yippie-Punk Continuum i Michael Stewart Foley To cite this version: Michael Stewart Foley. Political Pie-Throwing: Dead Kennedys and the Yippie-Punk Continuum i. Sonic Politics: Music and Social Movements in the Americas, 2019, 1138389390. hal-01999010 HAL Id: hal-01999010 https://hal.univ-grenoble-alpes.fr/hal-01999010 Submitted on 30 Jan 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Political Pie-Throwing: Dead Kennedys and the Yippie-Punk Continuumi MICHAEL STEWART FOLEY By the time Dead Kennedys released their first LP, Fresh Fruit for Rotting Vegetables, in 1980, the band had established itself as the leading American political punk band, hailing from a city that seemed to specialize in political art. In many ways, the band and its music represented the culmination of nearly three years of subcultural political struggle on a host of issues facing not only young people in San Francisco but American youth everywhere – enough that, to this day, many of the city’s punk veterans refer to their experience in the “movement.” Political historians of the United States in the 1970s and 1980s have mostly ignored punk, but this essay examines Dead Kennedys’ early career as a way to illuminate the political experience of one segment of American youth in the late 1970s. -

War of Position on Neoliberal Terrain

Interface: a journal for and about social movements Article Volume 5 (2): 377 - 398 (November 2013) Brissette, War of position on neoliberal terrain Waging a war of position on neoliberal terrain: critical reflections on the counter-recruitment movement Emily Brissette Abstract This paper explores the relationship between neoliberalism and the contemporary movement against military recruitment. It focuses on the way that the counter-recruitment movement is constrained by, reproduces, and in some instances challenges the reigning neoliberal common sense. Engaging with the work of Antonio Gramsci on ideological struggle (what he calls a war of position), the paper critically examines three aspects of counter-recruitment discourse for whether or how well they contribute to a war of position against militarism and neoliberalism. While in many instances counter-recruitment discourse is found to be imbricated with neoliberal assumptions, the paper argues that counter-recruitment work around the poverty draft offers a significant challenge, especially if it can be linked to broader struggles of social transformation. For more than thirty years, a number of peace organizations have waged a (mostly) quiet battle against the presence of military recruiters in American public schools. The war in Iraq brought these efforts to greater public awareness and swelled the ranks of counter-recruitment activists, as many came to see counter-recruitment as a way not only to contest but also to interfere directly with the execution of the war—by disrupting the flow of bodies into the military. While some of this disruption took physical form, as in civil disobedience or guerrilla theater to force the (temporary) closure of recruiting offices, much more of it has been discursive, attempting to counter the narratives the military uses to recruit young people. -

Winter 2020-21 Newsletter

Winter 2020-21, volume XXIV, issue 4 VETERANS FOR PEACE NEWS MINNEAPOLIS/ST. PAUL VETERANS FOR PEACE, CHAPTER 27 Veterans For Peace News is published quar- Save Our VA gets national backing, terly by Mpls./St. Paul Veterans For Peace, continues collaboration with unions Chapter 27. Veterans For Peace works to increase awareness of the costs of war, restrain our government from intervening in the internal affairs of other nations, end the arms race, reduce and even- tually eliminate nuclear weapons, seek justice for veterans and victims of war, and abolish war as an instrument of national policy. We pledge to use democratic and non- violent means to achieve our purpose. To subscribe to this newsletter, Save Our VA and the American Federation of Government Employees rally to stop the please call our office: 612-821-9141 privatization of the VA. Pictured above are VFP members Barry Riesch, Tom Dimond, Mike McDonald, Andy Berman, Dave Logsdon, Tom Bauch, Craig Wood and Jeff Roy Or write: and a number of AFGE union members. Photo from Union Advocate. Veterans For Peace Ch. 27 4200 Cedar Ave, S. #7 Minneapolis, MN 55407 by Arlys Herem and Jeff Roy, expand our efforts. Or e-mail: VFP SOVA Action Committee Minnesota The Campaign’s Outreach Sub- [email protected] Committee contacted over 200 past SOVA he Save Our VA (SOVA) and American activists and is working to build a national net- Our website is: TFederation of Government Employees work of local VFP Action Groups. The www.vfpchapter27.org. rally on October 29th at Hiawatha and Hwy. -

Gregory Sholette

GREGORY SHOLETTE Clearly the response by artists and academics to public events was far more direct and confrontational in the not-so-distant past than today. On May 2, 1970, members of the Art Workers Coalition and Guerrilla Art Action Group staged a mock gun battle in front of the Museum of Modern Art, and in 1976 a group of art historians and artists produced an anti-catalog denouncing the nationalism and racism of the bicentennial exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art. As late as the early 1980s, members of Group Material collaborated with an El Salvadorian support group to curate an exhibition opposed to United States pol- icy in Central America for a popular dance club, and the collective Political Art Documentation/Distribution paraded a blue, blimp-like Pac Man with the fea- tures of Uncle Sam in front of the White House. Militant street theater, inter- ventionist scholarship, activist curating, artists directly challenging their own well- being by denouncing museums and the art market—all of this appears inconceivable today. Perhaps the last artist-organized cultural campaign aimed at mass-mobilization in the United States was Artists Call Against Intervention in Central America in the mid-1980s. Organized primarily in New York City by veter- ans of the 1960s such as Leon Golub and Lucy Lippard (as well as younger organizers such as Doug Ashford of Group Material), Artists Call brought together younger artists, alternative spaces, small commercial dealers, and even a few major art galleries. Skillful organizing convinced these varied cultural partici- pants that acting to oppose U.S.