War of Position on Neoliberal Terrain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revisiting Maternalist Frames Across Cases of Women's Mobilization

WSIF-01856; No of Pages 12 Women's Studies International Forum 51 (2015) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Women's Studies International Forum journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/wsif “Resistance is fertile”1: Revisiting maternalist frames across cases of women’s mobilization Michelle E. Carreon a, Valentine M. Moghadam b a American Studies Program, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, USA b International Affairs Program and Dept. of Sociology, Northeastern University, Boston, MA, USA article info synopsis Available online xxxx Historically, governments and social movements have evoked images of mothers as nurturing, moral, peaceful, or combative agents. But how is a maternalist frame deployed in different contexts? Who deploys this frame, for what purposes and to what ends? In this article, we present a classification scheme to elucidate the diversity and versatility of maternalist frames through the examination of four distinct categories of cases of women's mobilization from the global South as well as North. Drawing on secondary literature and our own ongoing research, we construct a typology of maternalism-from-above and maternalism-from-below to demon- strate how maternalist frames may serve patriarchal or emancipatory purposes with implications for gender justice and the expansion of citizenship rights. © 2015 Published by Elsevier Ltd. In a 1984 photograph, Orlando Valenzuela depicts a smiling appear, and the diverse ways in which maternal identities are Sandinista woman breastfeeding an infant with an AK-47 invoked in political movements and processes, we revisit the strapped to her back. This image – as with previous ones literature and historical record to offer a classification that depicting Vietnamese militant mothers during the U.S. -

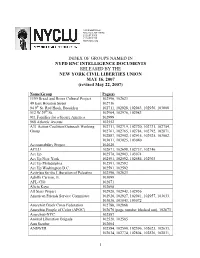

Index of Political Groups Mentioned in the Intelligence Documents

125 Broad Street New York, NY 10004 212.607.3300 212.607.3318 www.nyclu.org INDEX OF GROUPS NAMED IN NYPD RNC INTELLIGENCE DOCUMENTS RELEASED BY THE NEW YORK CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION MAY 16, 2007 (revised May 22, 2007) Name/Group Page(s) 1199 Bread and Roses Cultural Project 102596, 102623 49 East Houston Street 102716 94 9th St. Red Hook, Brooklyn 102711, 102928, 102943, 102956, 103008 512 W 29th St. 102964, 102976, 102983 911 Families for a Secure America 102999 968 Atlantic Avenue 102552 A31 Action Coalition/Outreach Working 102711, 102719, 102720, 102731, 102754, Group 102761, 102765, 102784, 102792, 102871, 102887, 102902, 102915, 102925, 103002, 103011, 103025, 103040 Accountability Project 102620 ACLU 102671, 102698, 102737, 102746 Act Up 102578, 102903, 103074 Act Up New York 102591, 102592, 102684, 102903 Act Up Philadelphia 102591, 102592 Act Up Washington D.C. 102591, 102592 Activists for the Liberation of Palestine 102596, 102623 Adolfo Carrion, Jr. 103099 AFL-CIO 102671 Alicia Keys 102698 All Stars Project 102928, 102943, 102956 American Friends Service Committee 102920, 102927, 102941, 102957, 103033, 103036, 103043, 103072 Anarchist Black Cross Federation 102788, 102868 Anarchist People of Color (APOC) 102670 (page number blacked out), 102673 Anarchist-NYC 102587 Animal Liberation Brigade 102520, 102585 Ann Stauber 102604 ANSWER 102584, 102590, 102596, 102623, 102633, 102634, 102774, 102804, 102826, 102831, 1 102843, 102884, 102900, 102906, 102916, 102919, 102926, 102940, 102952, 102959, 103068, 103076, 103092, 103096 Anthony -

Winter 2020-21 Newsletter

Winter 2020-21, volume XXIV, issue 4 VETERANS FOR PEACE NEWS MINNEAPOLIS/ST. PAUL VETERANS FOR PEACE, CHAPTER 27 Veterans For Peace News is published quar- Save Our VA gets national backing, terly by Mpls./St. Paul Veterans For Peace, continues collaboration with unions Chapter 27. Veterans For Peace works to increase awareness of the costs of war, restrain our government from intervening in the internal affairs of other nations, end the arms race, reduce and even- tually eliminate nuclear weapons, seek justice for veterans and victims of war, and abolish war as an instrument of national policy. We pledge to use democratic and non- violent means to achieve our purpose. To subscribe to this newsletter, Save Our VA and the American Federation of Government Employees rally to stop the please call our office: 612-821-9141 privatization of the VA. Pictured above are VFP members Barry Riesch, Tom Dimond, Mike McDonald, Andy Berman, Dave Logsdon, Tom Bauch, Craig Wood and Jeff Roy Or write: and a number of AFGE union members. Photo from Union Advocate. Veterans For Peace Ch. 27 4200 Cedar Ave, S. #7 Minneapolis, MN 55407 by Arlys Herem and Jeff Roy, expand our efforts. Or e-mail: VFP SOVA Action Committee Minnesota The Campaign’s Outreach Sub- [email protected] Committee contacted over 200 past SOVA he Save Our VA (SOVA) and American activists and is working to build a national net- Our website is: TFederation of Government Employees work of local VFP Action Groups. The www.vfpchapter27.org. rally on October 29th at Hiawatha and Hwy. -

WINTER 2011 Struggles in the Global South Note from the Co-Chair

The PEACECHRONICLE The Newsletter of the Peace and Justice Studies Association Spanning the globe Movements for PEACE emerge everywhere INSIDE THIS ISSUE: News, views, visions, and analyses of cutting-edge movements for peace! AN UPRISING IN EGYPT INTERNATIONAL PEACE TRIBUTE TO GREAT SOULS CHANGES IN GRATITUDE Plus… WINTER 2011 Struggles in the Global South Note from the Co-Chair ................................................ 3 2011 Conference Call .................................................... 4 Facilitating Group Learning The Director’s Cut........................................................ 6 2010 Conference Report-back News and Views ........................................................... 7 New Media Spotlight .................................................. 11 2011 Conference Proposal Call Join or Renew Now! PJSA Membership Form ............ 13 In Memoriam ............................................................. 14 RIP to Three Peacemaking Elders Sources ...................................................................... 18 Archer’s Arrows: Canon Fodder Archer’s Arrows ......................................................... 19 Jobs and Resources ..................................................... 20 Events Calendar ......................................................... 23 Creating a Just and Peaceful World through Research, Action, and Education THE PEACE CHRONICLE WINTER 2011 The Peace and Justice Studies Association Board of Directors Cris Toffolo - Co-Chair Michael Nagler - Co-Chair Matt Meyer - -

NO to NATO; YES to PEACE & DISARMAMENT COUNTER-SUMMIT International Peace Movement Conference

Join Us! NO TO NATO; YES TO PEACE & DISARMAMENT COUNTER-SUMMIT International Peace Movement Conference A S S I E C N S NW W DC NATO TURNS 70 In 2019 SPEAKERS INCLUDE NATO turns 70 in 2019 and will celebrate its Rev. Graylan Hagler Plymouth anniversary in Washington, D.C. on April 4, Martin Congregational United Church of Christ L K J D MLK (Washington) B V called on us to overcome the triple evils of Anna Ochkina - Institute of Globalization & militarism, racism and extreme materialism. Social Movements in Moscow (Russia) With the end of the Cold War, NATO should have been retired, not repurposed. NATO claims to Reiner Braun Co-President, International strive for collective defense and to preserve peace Peace Bureau (Berlin) and security. It has never been such a system. It is military spending and nuclear stockpiles. It is the Medea Benjamin Code Pink (Washington) main driver of the new arms race and the main obstacle to a nuclear weapons-free world. Having expanded across eastern Europe into former Soviet Peter Kuznick Professor of History, R American University (Washington) borders, its new nuclear weapons and a first-strike NATO driver of the new Cold War. It has also been transformed into a global military alliance structured to wage M E N A M E . Initiated by: American Friends Service Committee, No to War/No to NATO Network, Campaign for Peace, Disarmament and Common Security; International Peace Bureau; Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung and World Beyond War For more information see: www.no-to-nato.org ⚫ E-mail: [email protected] ⚫ Phone: 617-661-6134 Register at: bit.ly/april2conference NO TO NATO; YES TO PEACE & DISARMAMENT COUNTER-SUMMIT CONFERENCE AGENDA 9:30-9:45 Welcome Kristine Karch, No to war – No to NATO (Germany) Andreas Günther - Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung (New York) 9:45-10:45 Panel 1 Moderator: Kristine Karch 70 years of NATO - 70 years of Militarism and War Prof. -

Eye on Iran Accusations of a Clandestine Nuclear by John Steinbach Weapons Program

FOUNDED IN 1963 Our Fifth Decade WASHINGTON Working for SUBSCRIBE TODAY! Peace & Justice Peace Letter June, 2006 Published by the Washington Peace Center Vol. 42, No. 2 Eye on Iran accusations of a clandestine nuclear By John Steinbach weapons program. Even if Iran were pursuing The current efforts by the nuclear weapons, and there is not Bush administration to demonize one scintilla of evidence Iran have a strong sense of deja vu. supporting this accusation, As with the build-up to the according to the CIA it would take invasion of Iraq, they are engaging Iran ten years to develop nuclear in exaggeration, falsification of weapons. facts, and emotionalism to justify a In addition, even if Iran possible attack on Iran. developed nuclear weapons it would be national suicide were they to be used. (Iran is surrounded by nuclear states, Israel, Pakistan, 25 Years At The White House Gates India, Russia, and the United States in Iraq.) Longest Continuous Vigil Anywhere? See pages 5-8 These accusations of nuclear malfeasance reek of hypocrisy. Iran, a signatory to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, unlike India, Israel and Pakistan, has opened up its nuclear facilities to three years of unprecedented international inspections. Unfortunately, this time Bush is The only violations found were being aided and abetted by the issues of transparency. Meanwhile, Democrats, with Senators Clinton the United States, which is in gross and Lieberman, in particular, violation of the NPT for its refusal ratcheting up the pressure. to take steps toward total nuclear Brother Damu, DC Homeless The principal rationalization for disarmament, would never permit the drumbeats for war is Iran’s such inspections of its own nuclear We Miss You! Crisis nuclear research program, and facilities. -

July August Handful 12 Pages

1 Handful of Salt Volume XXXVXXXV,, Number 444 JulyJuly----August,August, 2011 Let’s re- engaging young people to increase their ignite the involvement in PJALS and to support youth-led torch: efforts. We will a 7-month leadership development program for young activists (ages Re-starting 16-22), from student groups, faith communities, our young and community groups as well as new PJALS activist members. We’ll offer a series of workshops on topics including corporate power, racial justice, leaders nonviolence and militarism, campaign planning, program! project coordination, conversations to move someone to take action, and effective meetings. By Liz Moore, PJALS Director Every month, program participants will volunteer with a group of their choice (including Since the early 80’s, PJALS’ vibrant youth PJALS of course!). program helped countless young people get a We want to provide a gathering place for taste for social justice. I started coming to the young people to ask questions, to educate each youth program (then called Youth for World other, and to explore social justice work Awareness) in 1991—I felt I’d found an oasis together. We can create a program unique for its of like-minded people from different high focus on hands-on organizing skills and we can schools, encouraging each other to ask help grow a vibrant network of young people questions and to educate ourselves about issues committed to social justice. we cared about in our world. I remember We need your help in two ways: impassioned conversations, making signs for 1. Will you donate now to help re-start this protests, and a fundraising concert. -

International Medical Corps Afghanistan

Heading Folder Afghanistan Afghanistan - Afghan Information Centre Afghanistan - International Medical Corps Afghanistan - Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan (RAWA) Agorist Institute Albee, Edward Alianza Federal de Pueblos Libres American Economic Association American Economic Society American Fund for Public Service, Inc. American Independent Party American Party (1897) American Political Science Association (APSA) American Social History Project American Spectator American Writer's Congress, New York City, October 9-12, 1981 Americans for Democratic Action Americans for Democratic Action - Students for Democractic Action Anarchism Anarchism - A Distribution Anarchism - Abad De Santillan, Diego Anarchism - Abbey, Edward Anarchism - Abolafia, Louis Anarchism - ABRUPT Anarchism - Acharya, M. P. T. Anarchism - ACRATA Anarchism - Action Resource Guide (ARG) Anarchism - Addresses Anarchism - Affinity Group of Evolutionary Anarchists Anarchism - Africa Anarchism - Aftershock Alliance Anarchism - Against Sleep and Nightmare Anarchism - Agitazione, Ancona, Italy Anarchism - AK Press Anarchism - Albertini, Henry (Enrico) Anarchism - Aldred, Guy Anarchism - Alliance for Anarchist Determination, The (TAFAD) Anarchism - Alliance Ouvriere Anarchiste Anarchism - Altgeld Centenary Committee of Illinois Anarchism - Altgeld, John P. Anarchism - Amateur Press Association Anarchism - American Anarchist Federated Commune Soviets Anarchism - American Federation of Anarchists Anarchism - American Freethought Tract Society Anarchism - Anarchist -

CODEPINK Media

CODEPINK Women for Peace media kit George Bush will eventually go back to Texas, but CODEPINK is here to stay” “ —Griff Jenkins, Fox News Someone once sang, “Bush stole the best years of my twenties,” and I think that’s true for most of my peers—not to mention the innocent lives of over a million Iraqis, thousands of soldiers and contractors, and people all over the world who have been impacted by US foreign policy. The Republican party’s politics of domination and consolidated executive power have become not only an embarrassment to the world, but also leading to a slow demise of our Constitution. I think there are republican values that are integral to our American culture, like fi scal conservatism, state and local rights and a focus on family, faith, and neighborhood organizing. I am going to “ the RNC not only to protest and agitate, but also to reclaim these ideals.” —Rae Abileah, Local Group Coordinator CODEPINK Founders and Staff Medea Benjamin is a cofounder of both CODEPINK and women’s movement for peace, the international human rights organization Global Exchange. and brings organizing resourc- She has been a tireless advocate for social justice for es to local coordinators. more than 20 years. Described as “one of America’s most committed —and most effective—fi ghters for human rights” Nancy Mancias is by New York Newsday, and called “one of the high profi le coordinating CODEPINK’s leaders of the peace movement” by the Los Angeles Times, presence at the RNC. She Medea has distinguished herself as an eloquent and energetic also serves as CODEPINK fi gure in the progressive movement. -

WCDMZ Letter to Trump Administration

President Donald Trump Secretary of State Rex Tillerson Secretary of Defense James Mattis H.R. McMaster, National Security Council April 26, 2017 Dear President Trump: We are women leaders from over 40 countries, including the Republic of Korea (ROK) and Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK), and many from nations that fought in the Korean War. We are from academia, business, civil society and the military, and represent a diversity of ethnicities, nationalities, religions, and political views. We are united by our belief that diplomacy is the only way to resolve the nuclear crisis and threat of war now facing the Korean peninsula. On July 27, 1953, leaders from the United States, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, and China signed the Armistice Agreement to halt the Korean War. They promised to re-convene within three months to replace the ceasefire with a binding peace agreement. This never occurred and an entrenched state of war has ever since defined inter-Korean and U.S.-D.P.R.K. relations. This war must end. Korea is the only nation to remain divided as a result of WWII. For three generations, millions of families have been separated by the world’s most militarized border. We urge you to do the following to avert war in Korea and bring about a long-desired peace on the peninsula: 1. Negotiate a freeze of North Korea’s nuclear and long-range ballistic program in exchange for a U.S. security guarantee that would include suspending U.S.-South Korea military exercises. 2. Initiate a peace process with North Korea, South Korea and China to replace the 1953 Armistice Agreement with a binding peace treaty to end the Korean War. -

Partisans, Nonpartisans, and the Antiwar Movement in the United

American Politics Research Volume 35 Number 4 July 2007 431-464 © 2007 Sage Publications Partisans, Nonpartisans, and 10.1177/1532673X07300763 http://apr.sagepub.com hosted at the Antiwar Movement in http://online.sagepub.com the United States Michael T. Heaney University of Florida Fabio Rojas Indiana University, Bloomington American social movements are often bitterly divided about whether their objectives are achieved better by working with one of the major political par- ties or by operating independently. These divisions are consequential for how social movements and political parties respond to one another. First, differing partisan attitudes shape the structure of activist networks, leading activists to join organizations with others who share their party loyalties or disloyalties. Second, partisan attitudes affect how activists participate in the movement, with strong partisans more likely to embrace institutional tactics, such as lob- bying. Third, partisanship affects activists’ access to the institutions of govern- ment, such as Congress. Relying on surveys of antiwar activists attending large-scale public demonstrations in 2004 and 2005 and a Capitol Hill Lobby Day in September 2005, the authors argue that some activists integrate into major party networks through the “party in the street,” an arena of significant party-movement interaction. Keywords: antiwar movement; social movements; political parties; party in the street; party identification; activist networks; social networks We believe that most of [House Minority Leader Nancy] Pelosi’s constituents perceive her as antiwar because they know only of her initial vote and her later public statements. We believe that we can pressure her by exposing the gap between her rhetoric and her votes and other leadership actions and inactions. -

LI Alliance for Peaceful Alternatives, the Shelter Rock Forum, Great

The UUCSR Shelter Rock Forum. Great Neck Sane /Peace Action and The LI Alliance for Peaceful Alternatives present A PERSONAL REPORT FROM GAZA ANN WRIGHT Wednesday, April 29, 2009, 7:30 p.m. Unitarian Universalist Congregation at Shelter Rock 48 Shelter Rock Road, Manhasset It was six years ago that Ann Wright resigned from the Bush administration and the U.S. diplomatic corps in opposition to the war on Iraq. Since then she has worked for peace in Iraq and has traveled for peace to other parts of the world, including Afghanistan, Cuba, Iran and Gaza. Her resignation freed Ms. Wright to speak freely about her concerns of the Bush administration’s war on Iraq, the treatment of prisoners in Guantanamo and Abu Ghraib and the curtailment of civil liberties under the Patriot Act. Recently Ann was part of a 58 person international delegation of women who traveled from Cairo to Gaza at the invitation of the U.N. Works and Relief Agency (UNWRA) on March 8th. It was to celebrate International Women's Day. The women of Gaza have little to celebrate. Of the 1400 Gazans killed during the recent Israeli attack 192 were women and 400 were children. Their homes and communities are destroyed. The struggle for food, fuel and the necessities of life goes on. They cannot understand why the world has remained silent about the Israeli military attacks and the 18 month blockade of their country. And yet they show a remarkable resilience. The women of Gaza celebrate their determination to survive. It is a remarkable story that you won't hear anywhere else.