Revisiting Maternalist Frames Across Cases of Women's Mobilization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Disappeared and Invisible Revealing the Enduring Impact of Enforced Disappearance on Women

International Center for Transitional Justice GENDER JUSTICE The Disappeared and Invisible Revealing the Enduring Impact of Enforced Disappearance on Women March 2015 Cover Image: In Raddoluwa, Sri Lanka, a woman pays tribute at a memorial to the disappeared, during a commemoration ceremony held annually on October 27. In the 1980s, thousands of Sri Lankans were disappeared in a wave of politically motivated abductions, torture, and killings. (Photo by Vikalpa, www.vikalpa.org/) GENDER JUSTICE The Disappeared and Invisible Revealing the Enduring Impact of Enforced Disappearance on Women March 2015 Polly Dewhirst and Amrita Kapur International Center The Disappeared and Invisible for Transitional Justice Acknowledgments The International Center for Transitional Justice gratefully acknowledges the generous financial support of UN Women, which made possible the research and writing of this report and two others on how enforced disappearance affects women: “Living with the Shadows of the Past: The Impact of Disappearance on Wives of the Missing in Lebanon” and “Beyond Relief: Addressing the Rights and Needs of Nepal’s Wives of the Disappeared.” In particular, ICTJ acknowledges Nahla Valji, of UN Women, who facilitated the conceptualization and development of this research project. The authors extend thanks to Cristián Correa, Senior Associate of ICTJ’s Reparations program, and Sibley Hawkins, Program Associate of ICTJ’s Gender Justice program, for their contributions. About the Authors Polly Dewhirst is an independent consultant with over 15 years of experience in research, advocacy, and psychosocial interventions in the fields of enforced disappearance and transitional justice. She has previously worked with CSVR in South Africa, ICTJ, and AJAR. -

Turkey 2020 Human Rights Report

TURKEY 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Turkey is a constitutional republic with an executive presidential system and a unicameral 600-seat parliament (the Grand National Assembly). In presidential and parliamentary elections in 2018, Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe observers expressed concern regarding restrictions on media reporting and the campaign environment, including the jailing of a presidential candidate that restricted the ability of opposition candidates to compete on an equal basis and campaign freely. The National Police and Jandarma, under the control of the Ministry of Interior, are responsible for security in urban areas and rural and border areas, respectively. The military has overall responsibility for border control and external security. Civilian authorities maintained effective control over law enforcement officials, but mechanisms to investigate and punish abuse and corruption remained inadequate. Members of the security forces committed some abuses. Under broad antiterror legislation passed in 2018 the government continued to restrict fundamental freedoms and compromised the rule of law. Since the 2016 coup attempt, authorities have dismissed or suspended more than 60,000 police and military personnel and approximately 125,000 civil servants, dismissed one-third of the judiciary, arrested or imprisoned more than 90,000 citizens, and closed more than 1,500 nongovernmental organizations on terrorism-related grounds, primarily for alleged ties to the movement of cleric Fethullah Gulen, whom the government accused of masterminding the coup attempt and designated as the leader of the “Fethullah Terrorist Organization.” Significant human rights issues included: reports of arbitrary killings; suspicious deaths of persons in custody; forced disappearances; torture; arbitrary arrest and continued detention of tens of thousands of persons, including opposition politicians and former members of parliament, lawyers, journalists, human rights activists, and employees of the U.S. -

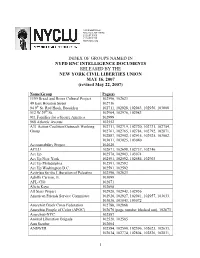

Index of Political Groups Mentioned in the Intelligence Documents

125 Broad Street New York, NY 10004 212.607.3300 212.607.3318 www.nyclu.org INDEX OF GROUPS NAMED IN NYPD RNC INTELLIGENCE DOCUMENTS RELEASED BY THE NEW YORK CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION MAY 16, 2007 (revised May 22, 2007) Name/Group Page(s) 1199 Bread and Roses Cultural Project 102596, 102623 49 East Houston Street 102716 94 9th St. Red Hook, Brooklyn 102711, 102928, 102943, 102956, 103008 512 W 29th St. 102964, 102976, 102983 911 Families for a Secure America 102999 968 Atlantic Avenue 102552 A31 Action Coalition/Outreach Working 102711, 102719, 102720, 102731, 102754, Group 102761, 102765, 102784, 102792, 102871, 102887, 102902, 102915, 102925, 103002, 103011, 103025, 103040 Accountability Project 102620 ACLU 102671, 102698, 102737, 102746 Act Up 102578, 102903, 103074 Act Up New York 102591, 102592, 102684, 102903 Act Up Philadelphia 102591, 102592 Act Up Washington D.C. 102591, 102592 Activists for the Liberation of Palestine 102596, 102623 Adolfo Carrion, Jr. 103099 AFL-CIO 102671 Alicia Keys 102698 All Stars Project 102928, 102943, 102956 American Friends Service Committee 102920, 102927, 102941, 102957, 103033, 103036, 103043, 103072 Anarchist Black Cross Federation 102788, 102868 Anarchist People of Color (APOC) 102670 (page number blacked out), 102673 Anarchist-NYC 102587 Animal Liberation Brigade 102520, 102585 Ann Stauber 102604 ANSWER 102584, 102590, 102596, 102623, 102633, 102634, 102774, 102804, 102826, 102831, 1 102843, 102884, 102900, 102906, 102916, 102919, 102926, 102940, 102952, 102959, 103068, 103076, 103092, 103096 Anthony -

Who's Who in Politics in Turkey

WHO’S WHO IN POLITICS IN TURKEY Sarıdemir Mah. Ragıp Gümüşpala Cad. No: 10 34134 Eminönü/İstanbul Tel: (0212) 522 02 02 - Faks: (0212) 513 54 00 www.tarihvakfi.org.tr - [email protected] © Tarih Vakfı Yayınları, 2019 WHO’S WHO IN POLITICS IN TURKEY PROJECT Project Coordinators İsmet Akça, Barış Alp Özden Editors İsmet Akça, Barış Alp Özden Authors Süreyya Algül, Aslı Aydemir, Gökhan Demir, Ali Yalçın Göymen, Erhan Keleşoğlu, Canan Özbey, Baran Alp Uncu Translation Bilge Güler Proofreading in English Mark David Wyers Book Design Aşkın Yücel Seçkin Cover Design Aşkın Yücel Seçkin Printing Yıkılmazlar Basın Yayın Prom. ve Kağıt San. Tic. Ltd. Şti. Evren Mahallesi, Gülbahar Cd. 62/C, 34212 Bağcılar/İstanbull Tel: (0212) 630 64 73 Registered Publisher: 12102 Registered Printer: 11965 First Edition: İstanbul, 2019 ISBN Who’s Who in Politics in Turkey Project has been carried out with the coordination by the History Foundation and the contribution of Heinrich Böll Foundation Turkey Representation. WHO’S WHO IN POLITICS IN TURKEY —EDITORS İSMET AKÇA - BARIŞ ALP ÖZDEN AUTHORS SÜREYYA ALGÜL - ASLI AYDEMİR - GÖKHAN DEMİR ALİ YALÇIN GÖYMEN - ERHAN KELEŞOĞLU CANAN ÖZBEY - BARAN ALP UNCU TARİH VAKFI YAYINLARI Table of Contents i Foreword 1 Abdi İpekçi 3 Abdülkadir Aksu 6 Abdullah Çatlı 8 Abdullah Gül 11 Abdullah Öcalan 14 Abdüllatif Şener 16 Adnan Menderes 19 Ahmet Altan 21 Ahmet Davutoğlu 24 Ahmet Necdet Sezer 26 Ahmet Şık 28 Ahmet Taner Kışlalı 30 Ahmet Türk 32 Akın Birdal 34 Alaattin Çakıcı 36 Ali Babacan 38 Alparslan Türkeş 41 Arzu Çerkezoğlu -

War of Position on Neoliberal Terrain

Interface: a journal for and about social movements Article Volume 5 (2): 377 - 398 (November 2013) Brissette, War of position on neoliberal terrain Waging a war of position on neoliberal terrain: critical reflections on the counter-recruitment movement Emily Brissette Abstract This paper explores the relationship between neoliberalism and the contemporary movement against military recruitment. It focuses on the way that the counter-recruitment movement is constrained by, reproduces, and in some instances challenges the reigning neoliberal common sense. Engaging with the work of Antonio Gramsci on ideological struggle (what he calls a war of position), the paper critically examines three aspects of counter-recruitment discourse for whether or how well they contribute to a war of position against militarism and neoliberalism. While in many instances counter-recruitment discourse is found to be imbricated with neoliberal assumptions, the paper argues that counter-recruitment work around the poverty draft offers a significant challenge, especially if it can be linked to broader struggles of social transformation. For more than thirty years, a number of peace organizations have waged a (mostly) quiet battle against the presence of military recruiters in American public schools. The war in Iraq brought these efforts to greater public awareness and swelled the ranks of counter-recruitment activists, as many came to see counter-recruitment as a way not only to contest but also to interfere directly with the execution of the war—by disrupting the flow of bodies into the military. While some of this disruption took physical form, as in civil disobedience or guerrilla theater to force the (temporary) closure of recruiting offices, much more of it has been discursive, attempting to counter the narratives the military uses to recruit young people. -

Winter 2020-21 Newsletter

Winter 2020-21, volume XXIV, issue 4 VETERANS FOR PEACE NEWS MINNEAPOLIS/ST. PAUL VETERANS FOR PEACE, CHAPTER 27 Veterans For Peace News is published quar- Save Our VA gets national backing, terly by Mpls./St. Paul Veterans For Peace, continues collaboration with unions Chapter 27. Veterans For Peace works to increase awareness of the costs of war, restrain our government from intervening in the internal affairs of other nations, end the arms race, reduce and even- tually eliminate nuclear weapons, seek justice for veterans and victims of war, and abolish war as an instrument of national policy. We pledge to use democratic and non- violent means to achieve our purpose. To subscribe to this newsletter, Save Our VA and the American Federation of Government Employees rally to stop the please call our office: 612-821-9141 privatization of the VA. Pictured above are VFP members Barry Riesch, Tom Dimond, Mike McDonald, Andy Berman, Dave Logsdon, Tom Bauch, Craig Wood and Jeff Roy Or write: and a number of AFGE union members. Photo from Union Advocate. Veterans For Peace Ch. 27 4200 Cedar Ave, S. #7 Minneapolis, MN 55407 by Arlys Herem and Jeff Roy, expand our efforts. Or e-mail: VFP SOVA Action Committee Minnesota The Campaign’s Outreach Sub- [email protected] Committee contacted over 200 past SOVA he Save Our VA (SOVA) and American activists and is working to build a national net- Our website is: TFederation of Government Employees work of local VFP Action Groups. The www.vfpchapter27.org. rally on October 29th at Hiawatha and Hwy. -

WINTER 2011 Struggles in the Global South Note from the Co-Chair

The PEACECHRONICLE The Newsletter of the Peace and Justice Studies Association Spanning the globe Movements for PEACE emerge everywhere INSIDE THIS ISSUE: News, views, visions, and analyses of cutting-edge movements for peace! AN UPRISING IN EGYPT INTERNATIONAL PEACE TRIBUTE TO GREAT SOULS CHANGES IN GRATITUDE Plus… WINTER 2011 Struggles in the Global South Note from the Co-Chair ................................................ 3 2011 Conference Call .................................................... 4 Facilitating Group Learning The Director’s Cut........................................................ 6 2010 Conference Report-back News and Views ........................................................... 7 New Media Spotlight .................................................. 11 2011 Conference Proposal Call Join or Renew Now! PJSA Membership Form ............ 13 In Memoriam ............................................................. 14 RIP to Three Peacemaking Elders Sources ...................................................................... 18 Archer’s Arrows: Canon Fodder Archer’s Arrows ......................................................... 19 Jobs and Resources ..................................................... 20 Events Calendar ......................................................... 23 Creating a Just and Peaceful World through Research, Action, and Education THE PEACE CHRONICLE WINTER 2011 The Peace and Justice Studies Association Board of Directors Cris Toffolo - Co-Chair Michael Nagler - Co-Chair Matt Meyer - -

NO to NATO; YES to PEACE & DISARMAMENT COUNTER-SUMMIT International Peace Movement Conference

Join Us! NO TO NATO; YES TO PEACE & DISARMAMENT COUNTER-SUMMIT International Peace Movement Conference A S S I E C N S NW W DC NATO TURNS 70 In 2019 SPEAKERS INCLUDE NATO turns 70 in 2019 and will celebrate its Rev. Graylan Hagler Plymouth anniversary in Washington, D.C. on April 4, Martin Congregational United Church of Christ L K J D MLK (Washington) B V called on us to overcome the triple evils of Anna Ochkina - Institute of Globalization & militarism, racism and extreme materialism. Social Movements in Moscow (Russia) With the end of the Cold War, NATO should have been retired, not repurposed. NATO claims to Reiner Braun Co-President, International strive for collective defense and to preserve peace Peace Bureau (Berlin) and security. It has never been such a system. It is military spending and nuclear stockpiles. It is the Medea Benjamin Code Pink (Washington) main driver of the new arms race and the main obstacle to a nuclear weapons-free world. Having expanded across eastern Europe into former Soviet Peter Kuznick Professor of History, R American University (Washington) borders, its new nuclear weapons and a first-strike NATO driver of the new Cold War. It has also been transformed into a global military alliance structured to wage M E N A M E . Initiated by: American Friends Service Committee, No to War/No to NATO Network, Campaign for Peace, Disarmament and Common Security; International Peace Bureau; Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung and World Beyond War For more information see: www.no-to-nato.org ⚫ E-mail: [email protected] ⚫ Phone: 617-661-6134 Register at: bit.ly/april2conference NO TO NATO; YES TO PEACE & DISARMAMENT COUNTER-SUMMIT CONFERENCE AGENDA 9:30-9:45 Welcome Kristine Karch, No to war – No to NATO (Germany) Andreas Günther - Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung (New York) 9:45-10:45 Panel 1 Moderator: Kristine Karch 70 years of NATO - 70 years of Militarism and War Prof. -

Eye on Iran Accusations of a Clandestine Nuclear by John Steinbach Weapons Program

FOUNDED IN 1963 Our Fifth Decade WASHINGTON Working for SUBSCRIBE TODAY! Peace & Justice Peace Letter June, 2006 Published by the Washington Peace Center Vol. 42, No. 2 Eye on Iran accusations of a clandestine nuclear By John Steinbach weapons program. Even if Iran were pursuing The current efforts by the nuclear weapons, and there is not Bush administration to demonize one scintilla of evidence Iran have a strong sense of deja vu. supporting this accusation, As with the build-up to the according to the CIA it would take invasion of Iraq, they are engaging Iran ten years to develop nuclear in exaggeration, falsification of weapons. facts, and emotionalism to justify a In addition, even if Iran possible attack on Iran. developed nuclear weapons it would be national suicide were they to be used. (Iran is surrounded by nuclear states, Israel, Pakistan, 25 Years At The White House Gates India, Russia, and the United States in Iraq.) Longest Continuous Vigil Anywhere? See pages 5-8 These accusations of nuclear malfeasance reek of hypocrisy. Iran, a signatory to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, unlike India, Israel and Pakistan, has opened up its nuclear facilities to three years of unprecedented international inspections. Unfortunately, this time Bush is The only violations found were being aided and abetted by the issues of transparency. Meanwhile, Democrats, with Senators Clinton the United States, which is in gross and Lieberman, in particular, violation of the NPT for its refusal ratcheting up the pressure. to take steps toward total nuclear Brother Damu, DC Homeless The principal rationalization for disarmament, would never permit the drumbeats for war is Iran’s such inspections of its own nuclear We Miss You! Crisis nuclear research program, and facilities. -

July August Handful 12 Pages

1 Handful of Salt Volume XXXVXXXV,, Number 444 JulyJuly----August,August, 2011 Let’s re- engaging young people to increase their ignite the involvement in PJALS and to support youth-led torch: efforts. We will a 7-month leadership development program for young activists (ages Re-starting 16-22), from student groups, faith communities, our young and community groups as well as new PJALS activist members. We’ll offer a series of workshops on topics including corporate power, racial justice, leaders nonviolence and militarism, campaign planning, program! project coordination, conversations to move someone to take action, and effective meetings. By Liz Moore, PJALS Director Every month, program participants will volunteer with a group of their choice (including Since the early 80’s, PJALS’ vibrant youth PJALS of course!). program helped countless young people get a We want to provide a gathering place for taste for social justice. I started coming to the young people to ask questions, to educate each youth program (then called Youth for World other, and to explore social justice work Awareness) in 1991—I felt I’d found an oasis together. We can create a program unique for its of like-minded people from different high focus on hands-on organizing skills and we can schools, encouraging each other to ask help grow a vibrant network of young people questions and to educate ourselves about issues committed to social justice. we cared about in our world. I remember We need your help in two ways: impassioned conversations, making signs for 1. Will you donate now to help re-start this protests, and a fundraising concert. -

Gefährdung Von IHD- Mitgliedern, Vorgehen Gegen «Samstagsmütter»

Türkei: Gefährdung von IHD- Mitgliedern, Vorgehen gegen «Samstagsmütter» Schnellrecherche der SFH-Länderanalyse Bern, 7. April 2020 Diese Recherche basiert auf Auskünften von Expertinnen und Experten und auf eigenen Recherchen. Entspre- chend den COI-Standards verwendet die SFH öffentlich zugängliche Quellen. Lassen sich im zeitlich begrenzten Rahmen der Recherche keine Informationen finden, werden Expertinnen und Experten beigez ogen. Die SFH do- kumentiert ihre Quellen transparent und nachvollziehbar. Aus Gründen des Quellenschutzes können Kontaktper- sonen anonymisiert werden. Impressum Herausgeberin Schweizerische Flüchtlingshilfe SFH Postfach, 3001 Bern Tel. 031 370 75 75 Fax 031 370 75 00 E-Mail: [email protected] Internet: www.fluechtlingshilfe.ch Spendenkonto: PC 30-1085-7 Sprachversionen Deutsch COPYRIGHT © 2020 Schweizerische Flüchtlingshilfe SFH, Bern Kopieren und Abdruck unter Quellenangabe erlaubt. Fragestellung Der Anfrage an die SFH-Länderanalyse sind die folgenden Fragen entnommen: 1. Besteht für Mitglieder und Führungspersonen der «İnsan Hakları Derneği» (Human Rights Association of Turkey, IHD) in der Türkei eine Gefährdung? Hat sich diese Gefährdung seit Herbst 2017 verschärft? 2. Gibt es Informationen zum Vorgehen gegen die «Samstagsmütter»? Die Informationen beruhen auf einer zeitlich begrenzten Recherche (Schnellrecherche) in öf- fentlich zugänglichen Dokumenten, die der SFH derzeit zur Verfügung stehen, sowie auf den Informationen von sachkundigen Kontaktpersonen. 1 Gefährdung von Menschen, die in «İnsan Hakları Derneği» (IHD) aktiv sind IHD. «İnsan Hakları Derneği» (IHD, in englischer Sprache Human Rights Association of Tur- key) ist nach eigenen Angaben die älteste Menschenrechtsorganisation in der Türkei. Nach eigenen Angaben ist IHD unter den Hauptakteuren in der Türkei, die im Menschenrechtsbe- reich tätig sind. IHD wurde 1986 gegründet und unterhielt im Juni 2019 insgesamt 26 Zweig- stellen und fünf sogenannte «Representatives Offices» und hatte knapp 8000 Mitglieder. -

International Medical Corps Afghanistan

Heading Folder Afghanistan Afghanistan - Afghan Information Centre Afghanistan - International Medical Corps Afghanistan - Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan (RAWA) Agorist Institute Albee, Edward Alianza Federal de Pueblos Libres American Economic Association American Economic Society American Fund for Public Service, Inc. American Independent Party American Party (1897) American Political Science Association (APSA) American Social History Project American Spectator American Writer's Congress, New York City, October 9-12, 1981 Americans for Democratic Action Americans for Democratic Action - Students for Democractic Action Anarchism Anarchism - A Distribution Anarchism - Abad De Santillan, Diego Anarchism - Abbey, Edward Anarchism - Abolafia, Louis Anarchism - ABRUPT Anarchism - Acharya, M. P. T. Anarchism - ACRATA Anarchism - Action Resource Guide (ARG) Anarchism - Addresses Anarchism - Affinity Group of Evolutionary Anarchists Anarchism - Africa Anarchism - Aftershock Alliance Anarchism - Against Sleep and Nightmare Anarchism - Agitazione, Ancona, Italy Anarchism - AK Press Anarchism - Albertini, Henry (Enrico) Anarchism - Aldred, Guy Anarchism - Alliance for Anarchist Determination, The (TAFAD) Anarchism - Alliance Ouvriere Anarchiste Anarchism - Altgeld Centenary Committee of Illinois Anarchism - Altgeld, John P. Anarchism - Amateur Press Association Anarchism - American Anarchist Federated Commune Soviets Anarchism - American Federation of Anarchists Anarchism - American Freethought Tract Society Anarchism - Anarchist