Framing Comedies of Recognition and Repertoires of Tactical Frivolity Within Social Movements A.T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Culture Jamming

Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank Vincent de Jong for introducing me to the intricacy of the easyCity action, and for taking the time to answer my questions along my exploration of the case. I also want to thank Robin van t’ Haar for his surprising, and unique, contribution to my investigations of the easyCity action. Rozalinda Borcila, the insights you have shared with me have been a crucial reminder of my own privilieged position – your reflections, I hope, also became a marker in what I have written. Also, I would like to thank others that somehow made my fieldwork possible, and influenced my ‘learning’ of activism and culture jamming. Of these I would especially like to thank Nina Haukeland for introducing me to the politics of activism, Kirsti Hyldmo for reminding me of the realities of exploitation, Åse Brandvold for a skilled introduction to the thoughts and tools of culture jamming, and Maria Astrup for showing me the pleasures and powers of aesthetics. Also, I would like to thank the Norwegian Adbusters Network, and the editorial groups of Vreng. To my main advisor Professor Kristian Stokke, I would like to thank you for the excellent support you have given me throughout my master studies. Your insights have been of grate value, and I cannot thank you enough for continually challenging me. Also, the feedback from Olve Krange, my second advisor, was crucial at the early stage of developing the thesis, to defining its object of inquiry, and finally when writing my conclusion. I would also like to express my appreciation to Professor Oddrun Sæther for an excellent introduction to the field of cultural studies, to Professor Matt Sparke at the University of Washington for demonstrating the intriguing complexities of political geography, and to PhD candidate Stephen Young, for proof reading and fruitful inputs at the final stage of writing. -

Re:Imagining Change

WHERE IMAGINATION BUILDS POWER RE:IMAGINING CHANGE How to use story-based strategy to win campaigns, build movements, and change the world by Patrick Reinsborough & Doyle Canning 1ST EDITION Advance Praise for Re:Imagining Change “Re:Imagining Change is a one-of-a-kind essential resource for everyone who is thinking big, challenging the powers-that-be and working hard to make a better world from the ground up. is innovative book provides the tools, analysis, and inspiration to help activists everywhere be more effective, creative and strategic. is handbook is like rocket fuel for your social change imagination.” ~Antonia Juhasz, author of e Tyranny of Oil: e World’s Most Powerful Industry and What We Must Do To Stop It and e Bush Agenda: Invading the World, One Economy at a Time “We are surrounded and shaped by stories every day—sometimes for bet- ter, sometimes for worse. But what Doyle Canning and Patrick Reinsbor- ough point out is a beautiful and powerful truth: that we are all storytellers too. Armed with the right narrative tools, activists can not only open the world’s eyes to injustice, but feed the desire for a better world. Re:Imagining Change is a powerful weapon for a more democratic, creative and hopeful future.” ~Raj Patel, author of Stuffed & Starved and e Value of Nothing: How to Reshape Market Society and Redefine Democracy “Yo Organizers! Stop what you are doing for a couple hours and soak up this book! We know the importance of smart “issue framing.” But Re:Imagining Change will move our organizing further as we connect to the powerful narrative stories and memes of our culture.” ~ Chuck Collins, Institute for Policy Studies, author of e Economic Meltdown Funnies and other books on economic inequality “Politics is as much about who controls meanings as it is about who holds public office and sits in office suites. -

Contesting Climate Change

CONTESTING CLIMATE CHANGE: CIVIL SOCIETY NETWORKS AND COLLECTIVE ACTION IN THE EUROPEAN UNION A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Jennifer Leigh Hadden August 2011 © 2011 Jennifer Leigh Hadden CONTESTING CLIMATE CHANGE: CIVIL SOCIETY NETWORKS AND COLLECTIVE ACTION IN THE EUROPEAN UNION Jennifer Leigh Hadden, Ph.D. Cornell University, 2011 Civil society organizations choose vastly different forms of collective action to try to influence European politics: everything from insider lobbying to disruptive protest, from public education to hunger strikes. Using network analysis and qualitative interviewing, my research emphasizes that patterns of inter-organizational relations influence organizational decisions to use one of these strategies. They do this by structuring the information and resources available to actors, as well as by diffusing strategies across connected actors. This is particularly true when networks are segmented into two distinct components, as I find in the European climate change network. In this network, organizations using contentious ‘outsider’ strategies are only loosely linked to those ‘insiders’ behaving conventionally in Brussels. These findings are policy relevant because current scholarship and policy recommendations tend to assume that increased civil society participation in transnational policy-making will increase democratic legitimacy. But my network data and qualitative interviews suggests that the emergence of a coalition of organizations engaging solely in contentious outsider action reflects the development and diffusion of a new and highly critical strand of climate change politics. I further argue that this type of contentious civil society ‘spillover’ can actually slow the pace of development of climate change policy and of European integration more generally. -

Exploring Emotional Intelligence Applications to Challenging Leadership Situations and Reputational Attacks

Exploring Emotional Intelligence Applications to Challenging Leadership Situations and Reputational Attacks Claudia Fernandez, DrPH, MS, RD, LDN Food Systems Leadership Institute February, 2019 Too few people live together in Harmony… It is true…Harmony is quite under-populated. But maybe that’s because we over-rely on the hard skills Hard Skills are the standard skills Budget and finance issues Delivery of clinical treatments or technical services Measurement Accounting Product Design and Development What are the biggest challenges? Budgets Strategic Planning Issues Organizational culture problems Inability to grasp the impacts of one’s actions Inability to communicate and understand one another Leading Managing Change Conflict Building Culture Developing a Team Kouzes & Posner Emotional Intelligence What you use when the hard skills simply can’t get you there And when you’re dealing with complexity, well, that likely to be a lot of the time… Aren’t smart people successful people? Yes, but…not universally People are hired for their technical knowledge, intelligence, and other related factors People derail in their careers over relationship issues—over issues of being unable to understand others, communicate with them, build bridges and alliances So there seems to be something else at play here… EI/EQ is a genuine ability to Build bridges and alliances Mend damaged relationships Empathize Be resilient Manage impulses and stress When do you first know things are off course? Unconsciously competent Consciously competent Consciously incompetent -

Hacking Global Justice Paper Prepared

Hacking Global Justice Paper prepared for: Changing Politics through Digital Networks October 5-6, 2007 Universitá degli Studi di Firenze Florence, Italy Jeffrey S. Juris Assistant Professor of Anthropology Department of Social & Behavioral Sciences New College of Interdisciplinary Arts & Sciences Arizona State University [email protected] Hacking Global Justice On November 30, 1999, as tens of thousands of protesters blockaded the World Trade Organization (WTO) Summit in Seattle, the electrohippies organized a simultaneous collective action in cyberspace. The U.K.-based collective, composed of environmentalists and computer programmers, developed a special website allowing activists from around the world to take part in a “virtual sit-in.” Using Floodnet software developed by the Electronic Disturbance Theater (EDT) during previous actions supporting the Zapatistas, the electrohippies’ site automatically transferred visitors en masse to the official WTO domain as if thousands of surfers repeatedly clicked their browser reload buttons at the same time. The action was designed to overload the WTO web server by sending multiple requests over a period of several days. The electrohippies claimed more than 450,000 people ultimately swamped the WTO site from November 30 to December 5, while participants sent an additional 900 e-mails to the server per day. The group later explained their action in this way, "In conventional sit-ins people try to occupy gateways or buildings. In a virtual sit-in people from around the globe can occupy the gateway to the WTO’s web servers. In this way we hope to block the flow of information from the conference- which is significant because it will cement proposals to expand globalization in the 21st Century."1 The virtual sit-in against the WTO is an example of what activists call Electronic Civil Disobedience (ECD), an information-age tactic intricately tied to an emerging wave of resistance against corporate globalization (cf. -

Evaluation Report 25 November 2020

Frame, Voice, Report! Final Evaluation Report 25 November 2020 Submitted by: Name: 4G eval s.r.o. Address: Pod Havlínem 217, 156 00 Praha 5, Czech Republic Contact Person: Marie Körner, [email protected] CONTENT Executive summary 1 1. Background 5 1.1. Introduction 5 1.2. Awareness raising of and engagement in SDGs in the EU 5 1.3. Program background 5 1.4. Objectives, use and scope of evaluation 7 1.5. Evaluation criteria and questions 7 1.6. Key evaluation stakeholders 8 2. METHODOLOGY 11 2.1. Approach 11 2.2. Data collection tools and methods 11 2.3. Data analysis and synthesis 13 2.4. Assumptions and limitations 13 3. FINDINGS 14 3.1. FVR! contribution to public awareness of & engagement in SDGs and 3 priorities (EQ1) 14 3.2. Key influencing factors of public awareness and engagement (EQ2) 20 3.3. FVR! contribution to outreach of grantees´ communication (EQ3) 23 3.4. How FVR! toolkit and learning process served grantees and media partners in understanding and using the FVR! principles (EQ4) 25 3.5. How the FVR! toolkit and learning process served grantees and media in working with the 3 thematic priorities (EQ5) 29 3.6. Unintended outcomes of FVR! for third parties (EQ6) 31 3.7. Effectiveness / efficiency of the sub-granting scheme management (EQ7) 33 3.8. Major takeaways for FVR! partners (EQ8+9) 36 3.9. Effectiveness of cooperation among FVR! partners (EQ10) 38 3.10. Unintended outcomes for FVR! partners (EQ11) 38 3.11. Unintended outcomes of in the target countries/regions (EQ12) 39 3.12. -

1 Conceptualising Horizontal Politics Eloїse Harding Thesis Submitted To

Conceptualising Horizontal Politics Eloїse Harding Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy July 2012 1 Abstract This project investigates the likelihood of a distinctive ideology emerging from what are known as ‘horizontal’ political movements – those which, in brief, aim to operate non-hierarchically guided by principles such as affinity – and furthermore to identify the potential components of such an ideology. The methodology is broadly based on that developed by Freeden, namely an analysis of the conceptual morphology of the ideas put out by horizontal movements. The sources used derive largely from the output of the movements themselves in various forms. I conclude that horizontal politics does have a recognisable ideological configuration, and that this is distinctive from other related ideologies such as anarchism. 2 Contents Introduction 4 Ideology: A Thematic History 31 The Background Literature 55 Hierarchy 76 Organisation 113 Power 145 Culture 176 Conclusion 203 Appendix 1 214 Appendix 2 215 Appendix 3 216 Bibliography 217 3 Introduction Aims, objectives and questions In general terms, this project aims to identify and examine the central ideas of the variety of political movement generally termed ‘horizontal’, and establish whether this political outlook constitutes a distinctive ideology. The question under discussion here is how such movements attempt to distinguish themselves. This investigation begins with the output of various elements of the horizontal ‘movement of movements’. The distinguishing features of such movements will be discussed in terms firstly of ethos and tactics and secondly of more theory-based reflections: both elements feed in to an overall investigation based on Freeden’s conceptualisation of an ideology as containing elements of both theory and practice. -

The Labour of Austerity: Absurdity, Performative Resistance, and Cultural Transformation

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research New York City College of Technology 2020 The Labour of Austerity: Absurdity, Performative Resistance, and Cultural Transformation Nora Almeida CUNY New York City College of Technology How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ny_pubs/688 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] The Labour of Austerity: Absurdity, Performative Resistance, and Cultural Transformation Nora Almeida New York City College of Technology ABSTR ACT This essay explores the social-psychic toll of prolonged austerity on academic librarians and the range of strategies that have (or could) serve as tools of resistance. Using a combination of theoretical analysis and autoethnography, I examine the emotional impact of bottomless and invisible labour imposed by austerity and the ways institutions use emotional coercion to promote self-surveillance, meta-work, and hyper-productivity. Following this analysis, I discuss the ways that oppressive institutional cultures silence dissent and absorb common resistance tactics advocated by educators. Finally, I introduce several examples of performance-based resistance projects and explore how creative, personal, and absurd forms of protest might be used to critique and transform the culture of work and our affective experience as knowledge workers in the neoliberal academy. Keywords: academic libraries · affect · performance · protest RÉSUMÉ Cet essai explore les conséquences sociopsychiques d’une austérité prolongée sur les bibliothécaires universitaires et la gamme de stratégies qui ont pu (ou pourraient) servir d’outils de résistance. -

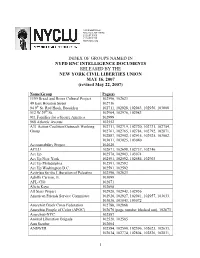

Index of Political Groups Mentioned in the Intelligence Documents

125 Broad Street New York, NY 10004 212.607.3300 212.607.3318 www.nyclu.org INDEX OF GROUPS NAMED IN NYPD RNC INTELLIGENCE DOCUMENTS RELEASED BY THE NEW YORK CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION MAY 16, 2007 (revised May 22, 2007) Name/Group Page(s) 1199 Bread and Roses Cultural Project 102596, 102623 49 East Houston Street 102716 94 9th St. Red Hook, Brooklyn 102711, 102928, 102943, 102956, 103008 512 W 29th St. 102964, 102976, 102983 911 Families for a Secure America 102999 968 Atlantic Avenue 102552 A31 Action Coalition/Outreach Working 102711, 102719, 102720, 102731, 102754, Group 102761, 102765, 102784, 102792, 102871, 102887, 102902, 102915, 102925, 103002, 103011, 103025, 103040 Accountability Project 102620 ACLU 102671, 102698, 102737, 102746 Act Up 102578, 102903, 103074 Act Up New York 102591, 102592, 102684, 102903 Act Up Philadelphia 102591, 102592 Act Up Washington D.C. 102591, 102592 Activists for the Liberation of Palestine 102596, 102623 Adolfo Carrion, Jr. 103099 AFL-CIO 102671 Alicia Keys 102698 All Stars Project 102928, 102943, 102956 American Friends Service Committee 102920, 102927, 102941, 102957, 103033, 103036, 103043, 103072 Anarchist Black Cross Federation 102788, 102868 Anarchist People of Color (APOC) 102670 (page number blacked out), 102673 Anarchist-NYC 102587 Animal Liberation Brigade 102520, 102585 Ann Stauber 102604 ANSWER 102584, 102590, 102596, 102623, 102633, 102634, 102774, 102804, 102826, 102831, 1 102843, 102884, 102900, 102906, 102916, 102919, 102926, 102940, 102952, 102959, 103068, 103076, 103092, 103096 Anthony -

The London School of Economics and Political Science The

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by LSE Theses Online The London School of Economics and Political Science The Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions Movement: Activism Across Borders for Palestinian Justice Suzanne Morrison A thesis submitted to the Department of Government of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, October 2015 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 75,359 words. 2 Abstract On 7 July 2005, a global call for Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) was declared to people around the world to enact boycott initiatives and pressure their respective governments to sanction Israel until it complies with international law and respects universal principles of human rights. The call was endorsed by over 170 Palestinian associations, trade unions, non-governmental organizations, charities, and other Palestinian groups. The call mentioned how broad BDS campaigns were utilized in the South African struggle against apartheid, and how these efforts served as an inspiration to those seeking justice for Palestinians. -

Dead Kennedys and the Yippie-Punk Continuum I Michael Stewart Foley

Political Pie-Throwing: Dead Kennedys and the Yippie-Punk Continuum i Michael Stewart Foley To cite this version: Michael Stewart Foley. Political Pie-Throwing: Dead Kennedys and the Yippie-Punk Continuum i. Sonic Politics: Music and Social Movements in the Americas, 2019, 1138389390. hal-01999010 HAL Id: hal-01999010 https://hal.univ-grenoble-alpes.fr/hal-01999010 Submitted on 30 Jan 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Political Pie-Throwing: Dead Kennedys and the Yippie-Punk Continuumi MICHAEL STEWART FOLEY By the time Dead Kennedys released their first LP, Fresh Fruit for Rotting Vegetables, in 1980, the band had established itself as the leading American political punk band, hailing from a city that seemed to specialize in political art. In many ways, the band and its music represented the culmination of nearly three years of subcultural political struggle on a host of issues facing not only young people in San Francisco but American youth everywhere – enough that, to this day, many of the city’s punk veterans refer to their experience in the “movement.” Political historians of the United States in the 1970s and 1980s have mostly ignored punk, but this essay examines Dead Kennedys’ early career as a way to illuminate the political experience of one segment of American youth in the late 1970s. -

The Efficacy of Virtual Protest: Linking Digital Tactics to Outcomes in Activist Campaigns

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Spring 6-19-2017 The Efficacy of Virtual Protest: Linking Digital Tactics to Outcomes in Activist Campaigns Rina Lynne James Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Sociology Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation James, Rina Lynne, "The Efficacy of Virtual Protest: Linking Digital Tactics to Outcomes in Activist Campaigns" (2017). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 4008. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.5892 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. The Efficacy of Virtual Protest: Linking Digital Tactics to Outcomes in Activist Campaigns by Rina Lynne James A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Science in Sociology Thesis Committee: Ginny Garcia-Alexander, Chair Amy Lubitow Robert Liebman Portland State University 2017 Abstract Activists are increasingly relying on online tactics and digital tools to address social issues. This shift towards reliance on the Internet has been shown to have salient implications for social movement formation processes; however, the effectiveness of such actions for achieving specific goals remains largely unaddressed. This study explores how the