1 Conceptualising Horizontal Politics Eloїse Harding Thesis Submitted To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Labour of Austerity: Absurdity, Performative Resistance, and Cultural Transformation

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research New York City College of Technology 2020 The Labour of Austerity: Absurdity, Performative Resistance, and Cultural Transformation Nora Almeida CUNY New York City College of Technology How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ny_pubs/688 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] The Labour of Austerity: Absurdity, Performative Resistance, and Cultural Transformation Nora Almeida New York City College of Technology ABSTR ACT This essay explores the social-psychic toll of prolonged austerity on academic librarians and the range of strategies that have (or could) serve as tools of resistance. Using a combination of theoretical analysis and autoethnography, I examine the emotional impact of bottomless and invisible labour imposed by austerity and the ways institutions use emotional coercion to promote self-surveillance, meta-work, and hyper-productivity. Following this analysis, I discuss the ways that oppressive institutional cultures silence dissent and absorb common resistance tactics advocated by educators. Finally, I introduce several examples of performance-based resistance projects and explore how creative, personal, and absurd forms of protest might be used to critique and transform the culture of work and our affective experience as knowledge workers in the neoliberal academy. Keywords: academic libraries · affect · performance · protest RÉSUMÉ Cet essai explore les conséquences sociopsychiques d’une austérité prolongée sur les bibliothécaires universitaires et la gamme de stratégies qui ont pu (ou pourraient) servir d’outils de résistance. -

The Labour of Austerity: Absurdity, Performative Resistance, and Cultural Transformation

The Labour of Austerity: Absurdity, Performative Resistance, and Cultural Transformation Nora Almeida New York City College of Technology ABSTR ACT This essay explores the social-psychic toll of prolonged austerity on academic librarians and the range of strategies that have (or could) serve as tools of resistance. Using a combination of theoretical analysis and autoethnography, I examine the emotional impact of bottomless and invisible labour imposed by austerity and the ways institutions use emotional coercion to promote self-surveillance, meta-work, and hyper-productivity. Following this analysis, I discuss the ways that oppressive institutional cultures silence dissent and absorb common resistance tactics advocated by educators. Finally, I introduce several examples of performance-based resistance projects and explore how creative, personal, and absurd forms of protest might be used to critique and transform the culture of work and our affective experience as knowledge workers in the neoliberal academy. Keywords: academic libraries · affect · performance · protest RÉSUMÉ Cet essai explore les conséquences sociopsychiques d’une austérité prolongée sur les bibliothécaires universitaires et la gamme de stratégies qui ont pu (ou pourraient) servir d’outils de résistance. En combinant l’analyse théorique et l’auto-ethnographie, j’examine l’impact émotionnel du travail sans fond et invisible imposé par l’austérité et les façons dont les établissements utilisent la coercition émotionnelle pour promouvoir l’autosurveillance, le métatravail -

Performing Protest. Media Practices in the Trans-Urban Euromayday Movement of the Precarious

Performing Protest. Media Practices in the Trans-Urban Euromayday Movement of the Precarious Marion Hamm Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences University of Lucerne (Switzerland) 2011 Approved by Prof. Dr. Oliver Marchart, University of Lucerne Prof. Dr. Klaus Schönberger, Zurich School of the Arts Uploaded 2015 to Luzern Open Repository Server http://nbn-resolving.de/urn/resolver.pl?urn=urn:nbn:ch:bel-85455 This doctoral thesis is hosted on LORY (Lucerne Open Repository) http://www.zhbluzern.ch Performing Protest: Media Practices of the Trans-Urban Euromayday Movement of the Precarious by Marion Hamm is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by- nc-nd/4.0/ (German translation: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de) or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. Citation: Hamm, Marion (2015): Performing Protest. Media Practices in the Trans-Urban Euromayday Movement of the Precarious. Doctoral Thesis, Faculty of Hu manities and Social Sciences, University of Lu- cerne, Switzerland (submitted 2011). Available from Lucerne Open Repository LORY: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn/resolver.pl?urn=urn:nbn:ch:bel-85455 ii Abstract This dissertation addresses the question of how contemporary social movements use protest media strategically in creative and productive ways that go beyond representation. Mediated repertoires of contention are brought into play to create new political subjectivities, establish credible political actors, and circulate struggles across regional and national borders. -

Küresel Ayaklanmalar Çağında Direniş Ve Estetik

Derleyenler AYLİN KURYEL - BEGÜM ÖZDEN FIRAT Küresel Ayaklanmalar Çağında Direniş ve Estetik AYLİN KURYEL doktorasını Amsterdam Üniversitesi Kültürel Analiz (ASCA) programında, görsel cemaatlerin oluşumunu milliyetçilik(ler) ve imaj politikaları arasındaki ilişkiye odaklanarak analiz ettiği tezle tamam- ladı. Milliyetçilik, görsel kültür, sanat ve direniş pratikleri üzerine çalış- maktadır. Cultural Activism: Practices, Dilemmas and Possibilities (Rodopi, 2011) kitabının editörlerinden biridir. Aynı zamanda, sanat projeleri, belgesel ve kısa filmler yapmaktadır. BEGÜM ÖZDEN FIRAT Mimar Sinan Güzel Sanatlar Üniversitesi Sosyo- loji Bölümü’nde öğretim üyesidir. Kent ve kültür sosyolojisi, görsel kültür çalışmaları ve toplumsal hareketler alanlarında çalışmaktadır. Commitment and Complicity in Cultural Theory and Practice (Palgrave/Macmillan, 2009) ve Cultural Activism: Practices, Dilemmas, Possibilities (Rodopi, 2011) kitaplarının editörlerindendir. Encounters with the Ottoman Miniature Contemporary Readings of an Imperial Art (2015) adlı kitabı I.B. Tauris tarafından yayımlanmıştır. sanathayat DİZİ EDİTÖRÜ Ali Artun Şayet avangard kavramının, estetik sanat rejiminde herhangi bir anlamı varsa, bu, hayattan kopuk sanatsal yenilikler icat etmesinde değil, gelecekteki bir hayatın duyulur formlarını ve maddi yapılarını icat etmesinde yatar. Jacques RANCIÈRE Derleyenler AYLİN KURYEL - BEGÜM ÖZDEN FIRAT Küresel Ayaklanmalar Çağında Direniş ve Estetik ÇEVİRENLER Birkan Taş - Elçin Gen - Ayşe Boren İletişim Yayınları 2165 • sanathayat dizisi 34 ISBN-13: 978-975-05-1771-6 © 2015 İletişim Yayıncılık A. Ş. 1. BASKI 2015, İstanbul • DİZİ EDİTÖRÜ Ali Artun YAYINA HAZIRLAYAN Elçin Gen KAPAK TASARIMI Özlem Özkal - Suat Aysu UYGULAMA Hüsnü Abbas DÜZELTİ Asude Ekinci DİZİN Elçin Gen BASKI ve CİLT Sena Ofset • SERTİFİKA NO. 12064 Litros Yolu 2. Matbaacılar Sitesi B Blok 6. Kat No. 4NB 7-9-11 Topkapı 34010 İstanbul Tel: 212.613 38 46 İletişim Yayınları SERTİFİKA NO. -

Neoliberal Capitalism, Political Repression As Discipline, and The

© COPYRIGHT by Jennifer D. Grubbs 2015 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED QUEER(EY)ING THE ECOTERRORIST: NEOLIBERAL CAPITALISM, POLITICAL REPRESSION AS DISCIPLINE, AND THE SPECTACLE OF DIRECT ACTION BY Jennifer D. Grubbs ABSTRACT The following analysis forges an innovative and interdisciplinary bridge between theory and practice that brings together an anthropological lens emphasizing local modes of knowledge, a communication lens underscoring rhetoric and environmental communication, and a digital media lens that stresses social media and e-communities. Through a mixed-methodology of critical discourse analysis, ethnography and performance studies, this project examines the ways in which anarchist antispeciesists co- construct and negotiate identity and power within physical and digital communities through disidentification. The project relied on a strong commitment to collaborative engagement with the research population and a queer disengagement with traditional social movement theories to expand the political imaginary through political theater. Activists utilize performative protest as both a methodology to disrupt hegemonic speciesism and also a playful solidification amongst politically repressed, geographically dispersed, oftentimes clandestine non-State actors. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The following project would not have been possible without the dedication and support from Dr. Daniel Sayers, Dr. William L. Leap, and Dr. Stephen Depoe. I am grateful for their theoretical guidance, their willingness to invest time and energy in my scholarship, and their confidence in my ability to succeed. I am eternally grateful to my mother, who provided countless hours of childcare while I typed away in my office. I am humbled by the community of anarchist antispeciesists that risk it all for the liberation of all beings. I am inspired, intrigued, and energized by their resolve and I am encouraged by the potentiality for change. -

The Political Aesthetics of Global Protest : the Arab Spring and Beyond, P

eCommons@AKU Individual Volumes ISMC Series 2014 The olitP ical Aesthetics of Global Protest : the Arab Spring and Beyond Pnina Werbner Editor Martin Webb Editor Kathryn Spellman-Poots Editor Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.aku.edu/uk_ismc_series_volumes Part of the African History Commons, Asian History Commons, Islamic World and Near East History Commons, and the Political History Commons Recommended Citation Werbner, P. , Webb, M. , Spellman-Poots, K. (Eds.). (2014). The Political Aesthetics of Global Protest : the Arab Spring and Beyond, p. 448. Available at: https://ecommons.aku.edu/uk_ismc_series_volumes/3 The Political Aesthetics of Global Protest The Arab Spring and Beyond Edited by Pnina Werbner, Martin Webb and Kathryn Spellman-Poots in association with THE AGA KHAN UNIVERSITY (International) in the United Kingdom Institute for the Study of Muslim Civilisations The opinions expressed in this volume are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Aga Khan University, Institute for the Study of Muslim Civilisations. © editorial matter and organisation Pnina Werbner, Martin Webb and Kathryn Spellman-Poots, 2014 © the chapters, their several authors, 2014 First published in hardback in 2014 by Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road 12 (2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh eh8 8pj www.euppublishing.com Typeset in Goudy Oldstyle by Koinonia, Manchester and printed and bound in Spain by Novoprint A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7486 9334 4 (hardback) ISBN 978 0 7486 9335 1 (paperback) ISBN 978 0 7486 9350 4 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 0 7486 9351 1 (epub) The right of the contributors to be identified as authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. -

Performing Vs. the Insurmountable: Theatrics, Activism, and Social Movements

Liminalities: A Journal of Performance Studies Vol. 4, No. 3, October 2008 Performing vs. the Insurmountable: Theatrics, Activism, and Social Movements Benjamin Shepard, L. M. Bogad, & Stephen Duncombe In recent years, observers have come to describe street protest and theatrical activism as both ineffective and even counterproductive (Weissberg). “[T]he protests of the last week in New York were more than a silly, off-key exercise in irrelevant chest-puffing. It was a colossal waste of political energy,” Matt Taibbi wrote shortly after the Republican National Convention in 2004. Taibbi was not alone in thinking this way. “It would be reasonable to observe this glaring lack of effect and conclude there’s no use, one might as well stay home,” Karen Loew wrote after Bush’s second inauguration, a few months later. Others would suggest the methods used by street activists involve multiple meanings requiring closer scrutiny (Chvasta; Shepard, Queer, Play ). Still others would suggest such theatrics require both distinct tactical application (Bogad, “Tactical,” Electoral) as well as critical re-assessment (Duncombe, Dream). As Taibbi noted, the “fun” which takes place during demonstration is no longer considered, “to be a Benjamin Shepard is Assistant Professor of Human Services at City Tech/City University of New York. He is author/editor of five books, including White Nights and Ascending Shadows: An Oral History of the San Francisco AIDS Epidemic (Cassell, 1997) and From ACT UP to the WTO: Urban Protest and Community Building in the Era of Globalization (Verso, 2002), as well as the upcoming Queer Political Performance and Protest (Routledge, 2009). -

Electronic Civil Disobedience

NOTICE CONCERNING COPYRIGHT RESTRICTIONS The copyright law of the United States [Title 17, United States Code] governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the reproduction is not to be used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research. If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excess of “fair use” that use may be liable for copyright infringement. The institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. No further reproduction and distribution of this copy is permitted by transmission or any other means. [ PMLA theories and methodologies Electronic Civil Disobedience: Inventing the We see that a certain revolutionary type is not possible, but at the same Future of Online time we comprehend that another revolutionary type becomes possible, not through a certain form of class struggle, but rather through a molecular rev- Agitprop Theater olution, which not only sets in motion social classes and individuals, but also a machinic and semiotic revolution. —Félix Guattari (qtd. in Raunig) #$%&#'( '()$*+,-. We follow the speed of dreams. —Subcomandante Insurgente Marcos, !e Speed of Dreams (2007) CRITICAL ART ENSEMBLE STAGED THE THEORY OF ELECTRONIC CIVIL DISOBEDIENCE (ECD) AS A GAMBLE AGAINST A FORM OF THE ALL- too- present future of “dead capital,” otherwise known as late capital. -

LCSH Section T

T (Computer program language) T cell growth factor T-Mobile G1 (Smartphone) [QA76.73.T] USE Interleukin-2 USE G1 (Smartphone) BT Programming languages (Electronic T-cell leukemia, Adult T-Mobile Park (Seattle, Wash.) computers) USE Adult T-cell leukemia UF Safe, The (Seattle, Wash.) T (The letter) T-cell leukemia virus I, Human Safeco Field (Seattle, Wash.) [Former BT Alphabet USE HTLV-I (Virus) heading] T-1 (Reading locomotive) (Not Subd Geog) T-cell leukemia virus II, Human Safeco Park (Seattle, Wash.) BT Locomotives USE HTLV-II (Virus) The Safe (Seattle, Wash.) T.1 (Torpedo bomber) T-cell leukemia viruses, Human BT Stadiums—Washington (State) USE Sopwith T.1 (Torpedo bomber) USE HTLV (Viruses) t-norms T-6 (Training plane) (Not Subd Geog) T-cell receptor genes USE Triangular norms UF AT-6 (Training plane) BT Genes T One Hundred truck Harvard (Training plane) T cell receptors USE Toyota T100 truck T-6 (Training planes) [Former heading] USE T cells—Receptors T. rex Texan (Training plane) T-cell-replacing factor USE Tyrannosaurus rex BT North American airplanes (Military aircraft) USE Interleukin-5 T-RFLP analysis Training planes T cells USE Terminal restriction fragment length T-6 (Training planes) [QR185.8.T2] polymorphism analysis USE T-6 (Training plane) UF T lymphocytes T. S. Hubbert (Fictitious character) T-18 (Tank) Thymus-dependent cells USE Hubbert, T. S. (Fictitious character) USE MS-1 (Tank) Thymus-dependent lymphocytes T. S. W. Sheridan (Fictitious character) T-18 light tank Thymus-derived cells USE Sheridan, T. S. W. (Fictitious -

Framing Comedies of Recognition and Repertoires of Tactical Frivolity Within Social Movements A.T

Interface: a journal for and about social movements Article Volume 8 (2): pp. 286 - 310 (November 2016) Kingsmith, Why so serious? Why so serious? Framing comedies of recognition and repertoires of tactical frivolity within social movements A.T. Kingsmith Abstract What makes something funny? That depends. When it comes to humour, we are all experts. We know what we find funny. Such ambiguity is one of the central reasons a phenomenological analysis of humour as a means for radical political subject formations has been neglected within the study of social movements. Yet in many contexts a joke can represent liberation from pressure, rebellion against authority, a subversive political performance. We might even say that given common social norms and linguistic signifiers, joke telling can tear holes in our usual predictions about the empirical world by creating disjunctions between actuality and representation. After all, those in power have little recourse against mockery. Responding harshly to silence humorous actions tends to in fact increase the laughter. As such, humour must be appreciated not just as comic relief, but as a form of ideological emancipation, a means of deconstructing our social realities, and at the same time, imagining and proposing alternative ones. By informing this notion of humour as subversive political performance with one of the most instrumental approaches to social movement studies, Charles Tilly’s repertoires of contention, this paper begins by framing the dangers of comedic containment, before theorising the creative and electronic turns in social movement studies through a lens of rebellious humour as a post-political act. The paper emphasises these contributions with two unique explorations of political humour: 1970s’ radio frivolity by the post-Marxist Italian Autonomous movement, and present day Internet frivolousness by the hacktivist collective Anonymous. -

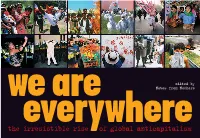

The Irresistible Rise of Global Anticapitalism for Struggling for a Better World All of Us Are Fenced In, Threatened with Death

edited by we are Notes from Nowhere everywhere the irresistible rise of global anticapitalism For struggling for a better world all of us are fenced in, threatened with death. The fence is reproduced globally. In every continent, every city, every countryside, every house. Power’s fence of war closes in on the rebels, for whom humanity is always grateful. But fences are broken. The rebels, whom history repeatedly has given the length of its long trajectory, struggle and the fence is broken. The rebels search each other out. They walk toward one another. They find each other and together break other fences. First published by Verso 2003 The texts in this book are copyleft (except where indicated). The © All text copyleft for non-profit purposes authors and publishers permit others to copy, distribute, display, quote, and create derivative works based upon them in print and electronic 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 format for any non-commercial, non-profit purposes, on the conditions that the original author is credited, We Are Everywhere is cited as a source Verso along with our website address, and the work is reproduced in the spirit of UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG the original. The editors would like to be informed of any copies produced. USA: 180 Varick Street, New York, NY 10014-4606 Reproduction of the texts for commercial purposes is prohibited www.versobooks.com without express permission from the Notes from Nowhere editorial collective and the publishers. All works produced for both commercial Verso is the imprint of New Left Books and non-commercial purposes must give similar rights and reproduce the copyleft clause within the publication. -

Affective Political Activism in Participatory Online Communities Paromita Sengupta University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations May 2015 "Boredom Is Always Counter-revolutionary": Affective Political Activism in Participatory Online Communities Paromita Sengupta University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Sengupta, Paromita, ""Boredom Is Always Counter-revolutionary": Affective Political Activism in Participatory Online Communities" (2015). Theses and Dissertations. 923. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/923 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “BOREDOM IS ALWAYS COUNTER-REVOLUTIONARY”: AFFECTIVE POLITICAL ACTIVISM IN PARTICIPATORY ONLINE COMMUNITIES by Paromita Sengupta A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Media Studies at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee May 2015 ABSTRACT “BOREDOM IS ALWAYS COUNTER-REVOLUTIONARY”: AFFECTIVE POLITICAL ACTIVISM IN PARTICIPATORY ONLINE COMMUNITIES by Paromita Sengupta The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2015 Under the Supervision of Dr. Michael Newman My thesis examines how fan communities on Facebook can become centres of political activism, operating through members’ affective ties to the cause and community, and networked communication. I conduct an ethnographic study of two Facebook communities—the street-photography page Humans of New York, and the page of the anonymous internet comedian who calls himself the Facebook God. Through a discursive analysis of the content of these pages and socio-political issues discussed by the members, I try demonstrate that Facebook activism can serve as an important gateway to civic engagement, through affective politics and connective action.