Carnivalesque Protest in Occupy Wall Street

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Culture Jamming

Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank Vincent de Jong for introducing me to the intricacy of the easyCity action, and for taking the time to answer my questions along my exploration of the case. I also want to thank Robin van t’ Haar for his surprising, and unique, contribution to my investigations of the easyCity action. Rozalinda Borcila, the insights you have shared with me have been a crucial reminder of my own privilieged position – your reflections, I hope, also became a marker in what I have written. Also, I would like to thank others that somehow made my fieldwork possible, and influenced my ‘learning’ of activism and culture jamming. Of these I would especially like to thank Nina Haukeland for introducing me to the politics of activism, Kirsti Hyldmo for reminding me of the realities of exploitation, Åse Brandvold for a skilled introduction to the thoughts and tools of culture jamming, and Maria Astrup for showing me the pleasures and powers of aesthetics. Also, I would like to thank the Norwegian Adbusters Network, and the editorial groups of Vreng. To my main advisor Professor Kristian Stokke, I would like to thank you for the excellent support you have given me throughout my master studies. Your insights have been of grate value, and I cannot thank you enough for continually challenging me. Also, the feedback from Olve Krange, my second advisor, was crucial at the early stage of developing the thesis, to defining its object of inquiry, and finally when writing my conclusion. I would also like to express my appreciation to Professor Oddrun Sæther for an excellent introduction to the field of cultural studies, to Professor Matt Sparke at the University of Washington for demonstrating the intriguing complexities of political geography, and to PhD candidate Stephen Young, for proof reading and fruitful inputs at the final stage of writing. -

Copyright by Judith A. Thomas 2012

Copyright by Judith A. Thomas 2012 The Thesis Committee for Judith A. Thomas Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Live Stream Micro-Media Activism in the Occupy Movement Mediatized Co-presence, Autonomy, and the Ambivalent Face APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Karin Gwinn Wilkins Joseph D. Straubhaar Live Stream Micro-Media Activism in the Occupy Movement Mediatized Co-presence, Autonomy, and the Ambivalent Face by Judith A. Thomas, BFA Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 Dedication For my husband, inspiration and co-conspirator, Rob Donald. (Photo: The First Adbusters’ Poster for Occupy Wall Street, September 2011. Acknowledgements The work of Manuel Castells on autonomous networks and communication power has had a profound impact on this scholarship. The breadth of his vision and theoretical analysis is inspiring and insightful. I hope this work contributes to the continuing critical cultural discussion of the potential of citizen micro-media in all contexts but especially the international uprisings of 2010-2012. Most especially, my sincere thanks to the following University of Texas at Austin professors whose knowledge and curiosity inspired me most: Joe Straubhaar, Paul Resta, Shanti Kumar, Sandy Stone, and especially my generous, gifted and patient supervisor, Karin Gwinn Wilkins. I will miss the depth and breadth of debate we shared, and I look forward to following your challenging work in the future. v Abstract Live Stream Micro-Media Activism in the Occupy Movement Mediatized Co-presence, Autonomy, and the Ambivalent Face Judith A. -

Re:Imagining Change

WHERE IMAGINATION BUILDS POWER RE:IMAGINING CHANGE How to use story-based strategy to win campaigns, build movements, and change the world by Patrick Reinsborough & Doyle Canning 1ST EDITION Advance Praise for Re:Imagining Change “Re:Imagining Change is a one-of-a-kind essential resource for everyone who is thinking big, challenging the powers-that-be and working hard to make a better world from the ground up. is innovative book provides the tools, analysis, and inspiration to help activists everywhere be more effective, creative and strategic. is handbook is like rocket fuel for your social change imagination.” ~Antonia Juhasz, author of e Tyranny of Oil: e World’s Most Powerful Industry and What We Must Do To Stop It and e Bush Agenda: Invading the World, One Economy at a Time “We are surrounded and shaped by stories every day—sometimes for bet- ter, sometimes for worse. But what Doyle Canning and Patrick Reinsbor- ough point out is a beautiful and powerful truth: that we are all storytellers too. Armed with the right narrative tools, activists can not only open the world’s eyes to injustice, but feed the desire for a better world. Re:Imagining Change is a powerful weapon for a more democratic, creative and hopeful future.” ~Raj Patel, author of Stuffed & Starved and e Value of Nothing: How to Reshape Market Society and Redefine Democracy “Yo Organizers! Stop what you are doing for a couple hours and soak up this book! We know the importance of smart “issue framing.” But Re:Imagining Change will move our organizing further as we connect to the powerful narrative stories and memes of our culture.” ~ Chuck Collins, Institute for Policy Studies, author of e Economic Meltdown Funnies and other books on economic inequality “Politics is as much about who controls meanings as it is about who holds public office and sits in office suites. -

Popular Movements in Public Space a Geographical Analysis of Occupy Wall Street

Department of Global Studies and Geography Popular Movements in Public Space A Geographical Analysis of Occupy Wall Street James Yantis Geography Honors Essay Advisor: Kari B. Jensen Received High Honors 2012 Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 2 Popular Movements...................................................................................................................................... 2 Beginning of OWS ......................................................................................................................................... 8 Methodology ............................................................................................................................................... 10 Regional Analysis......................................................................................................................................... 17 Public Space ................................................................................................................................................ 19 Public Identities ........................................................................................................................................... 24 Public eviction ............................................................................................................................................. 27 Concluding Remarks................................................................................................................................... -

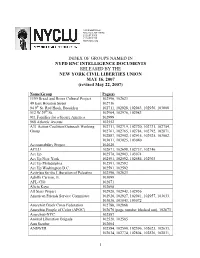

Index of Political Groups Mentioned in the Intelligence Documents

125 Broad Street New York, NY 10004 212.607.3300 212.607.3318 www.nyclu.org INDEX OF GROUPS NAMED IN NYPD RNC INTELLIGENCE DOCUMENTS RELEASED BY THE NEW YORK CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION MAY 16, 2007 (revised May 22, 2007) Name/Group Page(s) 1199 Bread and Roses Cultural Project 102596, 102623 49 East Houston Street 102716 94 9th St. Red Hook, Brooklyn 102711, 102928, 102943, 102956, 103008 512 W 29th St. 102964, 102976, 102983 911 Families for a Secure America 102999 968 Atlantic Avenue 102552 A31 Action Coalition/Outreach Working 102711, 102719, 102720, 102731, 102754, Group 102761, 102765, 102784, 102792, 102871, 102887, 102902, 102915, 102925, 103002, 103011, 103025, 103040 Accountability Project 102620 ACLU 102671, 102698, 102737, 102746 Act Up 102578, 102903, 103074 Act Up New York 102591, 102592, 102684, 102903 Act Up Philadelphia 102591, 102592 Act Up Washington D.C. 102591, 102592 Activists for the Liberation of Palestine 102596, 102623 Adolfo Carrion, Jr. 103099 AFL-CIO 102671 Alicia Keys 102698 All Stars Project 102928, 102943, 102956 American Friends Service Committee 102920, 102927, 102941, 102957, 103033, 103036, 103043, 103072 Anarchist Black Cross Federation 102788, 102868 Anarchist People of Color (APOC) 102670 (page number blacked out), 102673 Anarchist-NYC 102587 Animal Liberation Brigade 102520, 102585 Ann Stauber 102604 ANSWER 102584, 102590, 102596, 102623, 102633, 102634, 102774, 102804, 102826, 102831, 1 102843, 102884, 102900, 102906, 102916, 102919, 102926, 102940, 102952, 102959, 103068, 103076, 103092, 103096 Anthony -

Dead Kennedys and the Yippie-Punk Continuum I Michael Stewart Foley

Political Pie-Throwing: Dead Kennedys and the Yippie-Punk Continuum i Michael Stewart Foley To cite this version: Michael Stewart Foley. Political Pie-Throwing: Dead Kennedys and the Yippie-Punk Continuum i. Sonic Politics: Music and Social Movements in the Americas, 2019, 1138389390. hal-01999010 HAL Id: hal-01999010 https://hal.univ-grenoble-alpes.fr/hal-01999010 Submitted on 30 Jan 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Political Pie-Throwing: Dead Kennedys and the Yippie-Punk Continuumi MICHAEL STEWART FOLEY By the time Dead Kennedys released their first LP, Fresh Fruit for Rotting Vegetables, in 1980, the band had established itself as the leading American political punk band, hailing from a city that seemed to specialize in political art. In many ways, the band and its music represented the culmination of nearly three years of subcultural political struggle on a host of issues facing not only young people in San Francisco but American youth everywhere – enough that, to this day, many of the city’s punk veterans refer to their experience in the “movement.” Political historians of the United States in the 1970s and 1980s have mostly ignored punk, but this essay examines Dead Kennedys’ early career as a way to illuminate the political experience of one segment of American youth in the late 1970s. -

Revisions to Prohibitions and Restrictions on Proprietary Trading and Certain Interests In, and Relationships With, Hedge Funds and Private Equity Funds

DEPARTMENT OF TREASURY Office of the Comptroller of the Currency 12 CFR Part 44 Docket No. OCC-2018-0010 RIN 1557-AE27 FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM 12 CFR Part 248 Docket No. R-1608 RIN 7100-AF 06 FEDERAL DEPOSIT INSURANCE CORPORATION 12 CFR Part 351 RIN 3064-AE67 SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION 17 CFR Part 255 Release no. BHCA-[#]; File no. [###] RIN 3235-AM10 COMMODITY FUTURES TRADING COMMISSION 17 CFR Part 75 RIN 3038-AE72 Revisions to Prohibitions and Restrictions on Proprietary Trading and Certain Interests in, and Relationships With, Hedge Funds and Private Equity Funds AGENCY: Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, Treasury (OCC); Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (Board); Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC); Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC); and Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC). ACTION: Final rule. SUMMARY: The OCC, Board, FDIC, SEC, and CFTC are adopting amendments to the regulations implementing section 13 of the Bank Holding Company Act. Section 13 contains certain restrictions on the ability of a banking entity and nonbank financial company supervised by the Board to engage in proprietary trading and have certain interests in, or relationships with, a hedge fund or private equity fund. These final amendments are intended to provide banking entities with clarity about what activities are prohibited and to improve supervision and implementation of section 13. DATES: Effective Date: The effective date for this release is January 1, 2020. Compliance Date: Banking entities must comply with the final amendments by January 1, 2021. The 2013 rule will remain in effect until the compliance date, and a banking entity must continue to comply with the 2013 rule. -

Looking Back on 2013

THIS WEEK IN WALL STREET REFORM December 28 – January 3, 2014 We encourage you to forward this weekly compilation to friends and colleagues. To subscribe, email [email protected], with “This Week” in the subject line LOOKING BACK ON 2013 Financial Reform Went Way Better than Expected Mike Konczal, New Republic, 12/29/13. “[N]obody thought that banks would face tougher holding requirements for capital, that regulations of the financial derivatives markets would advance, or that the final Volcker [Rule] would be a pretty good start instead of an incoherent mess. Yet that is what appears to have happened in 2013.” “JPMorgan had been leading the charge against reform, arguing that the effort was over-harsh and destructive, and that Wall Street had already cleaned up its act on its own. Indeed, the big concern in 2012 was that Wall Street would convince enough moderate Democrats that Dodd- Frank had gone too far… and Congress would stop regulatory action before it was even completed. This fell apart right alongside the multi-billion dollar losses in JPMorgan’s position. “Though small compared to Wall Street and the right, groups like Americans for Financial Reform and Better Markets show up extensively in the comments on the Volcker Rule. In the final rule, there are hundreds of references to the detailed comment letter the Occupy the SEC group sent. These groups didn’t exist before the crisis, and their existence is a major piece of what makes solid final rules happen.” Regulators Halfway Home on Dodd-Frank Peter Schroeder, The Hill, 1/2/14 “More than half of the Dodd-Frank financial reform law has been fully implemented three and a half years after its enactment. -

Gregory Sholette

GREGORY SHOLETTE Clearly the response by artists and academics to public events was far more direct and confrontational in the not-so-distant past than today. On May 2, 1970, members of the Art Workers Coalition and Guerrilla Art Action Group staged a mock gun battle in front of the Museum of Modern Art, and in 1976 a group of art historians and artists produced an anti-catalog denouncing the nationalism and racism of the bicentennial exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art. As late as the early 1980s, members of Group Material collaborated with an El Salvadorian support group to curate an exhibition opposed to United States pol- icy in Central America for a popular dance club, and the collective Political Art Documentation/Distribution paraded a blue, blimp-like Pac Man with the fea- tures of Uncle Sam in front of the White House. Militant street theater, inter- ventionist scholarship, activist curating, artists directly challenging their own well- being by denouncing museums and the art market—all of this appears inconceivable today. Perhaps the last artist-organized cultural campaign aimed at mass-mobilization in the United States was Artists Call Against Intervention in Central America in the mid-1980s. Organized primarily in New York City by veter- ans of the 1960s such as Leon Golub and Lucy Lippard (as well as younger organizers such as Doug Ashford of Group Material), Artists Call brought together younger artists, alternative spaces, small commercial dealers, and even a few major art galleries. Skillful organizing convinced these varied cultural partici- pants that acting to oppose U.S. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 104 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 104 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 142 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, MARCH 6, 1996 No. 29 House of Representatives The House met at 11 a.m. Mr. TRAFICANT led the Pledge of required that he remove those sections The Chaplain, Rev. James David Allegiance as follows: of the Palestine National Covenant Ford, D.D., offered the following pray- I pledge allegiance to the Flag of the Unit- which call for the destruction of Israel. er: ed States of America, and to the Republic for Until such time as Arafat lives up to Your goodness to us, O God, is be- which it stands, one nation under God, indi- those agreements he has signed and yond our measure and Your grace to us visible, with liberty and justice for all. eliminates Hamas from areas for which is not restrained. In spite of missing f he bears responsibility, the United the mark and seeing too much our own MESSAGE FROM THE SENATE States should know that there is little way, You allow your blessings to flow A message from the Senate by Mr. good in negotiating with him. and Your mercies never to cease. We Lundregan, one of its clerks, an- f pray that this day we will open our nounced that the Senate agrees to the hearts and minds to the daily gifts of report of the committee of conference HEALTH INSURANCE COVERAGE faith and hope and love and pray that on the disagreeing votes of the two (Mr. -

December 13, 2013

THIS WEEK IN WALL STREET REFORM December 7 – December 13, 2013 We encourage you to forward this weekly compilation to friends and colleagues. To subscribe, email [email protected], with “This Week” in the subject line VOLCKER RULE Regulators Adopt Final Volcker Rule Limits on Bank Trading Danielle Douglas, Washington Post, 12/10/13 “Government regulators ushered in a new era of oversight Tuesday aimed at reining in Wall Street risk-taking, voting to prevent big banks from trading for their own benefit. “The ‘Volcker rule,’ named after former Federal Reserve chairman Paul Volcker, also bars banks from owning hedge funds and private-equity funds. The centerpiece of the 2010 Dodd- Frank financial overhaul law took three years to complete as government infighting and intense lobbying by banks slowed the process. “’The strength of the rule is the scope of the compliance regime,’ said Marcus Stanley, policy director of Americans for Financial Reform. ‘The regulators correctly realized that most proprietary trading is hidden within supposedly innocent activities like hedging or market- making.’ “He said the rule offers guidelines that are only as effective as the regulators that implement them.” Banks Need the Volcker Rule Editorial, USA Today, 12/9/13 “Wall Street lobbyists worked furiously for three years to water the rule down, ultimately producing a complex document of nearly 1,000 pages, including the preamble. A simpler rule would have been less easily abused. But the basic principle remains sound: High-risk trading should be left to hedge funds and other institutions that are small enough to fail without bringing down whole economies. -

Reclaim the Streets! from Local to Global Party Protest

THIRD TEXT Critical Perspectives on Contemporary Art and Culture July 2013 Reclaim The Streets! From Local to Global Party Protest Julia Ramírez Blanco If I can’t dance it’s not my revolution.1 Over the years, we have become used to experiencing works of art instead of merely watching them. As spectators, we are asked to become participants in what are considered to be artistic ‘situations’. The institutional and academic worlds propose terms such as ‘relational art’ or ‘community art’.2 A certain neo-situationist theoretical current introduces quotes of Guy Debord, Jean Baudrillard, Raoul Vaneigem and Michel de Certeau into the texts that deal with these practices. In considering these developments, Claire Bishop has spoken of a ‘social turn’ in contemporary art. However, in the introduction to her book Artificial Hells (2012), she states that this might actually be a return, and that such a return belongs to a certain tradition: From a Western European perspective, the social turn in contemporary art can be contextualized by two previous historical moments, both synonymous with political upheaval and movements for social change: the historic avant-garde in Europe circa 1917, and the so-called ‘neo’ avant-garde leading to 1968. The conspicuous resurgence of participatory art in the 1990s leads me to posit the fall of communism in 1989 as a third point of transformation. Triangulated, these three dates form a narrative of the triumph, heroic last stand and collapse of a collectivist vision of society. Each phase has been accompanied by a utopian rethinking of art’s relationship to the social and of its political potential – manifested in a reconsideration of the ways in which art is produced, consumed and debated.3 As had happened with previous explosions of participation in the art field, the renewed interest in participation of the 1990s cannot be fully understood without looking at what was happening at the same time in the field of activism.