Reclaim the Streets! from Local to Global Party Protest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reclaim the Streets, the Protestival and the Creative Transformation of the City

Finisterra, XLVii, 94, 2012, pp. 103-118103 RECLAIM THE STREETS, THE PROTESTIVAL aND THE CREaTiVE TRaNSFoRMaTioN oF THE CiTY anDré carMo1 abstract – the main goal of this article is to reflect upon the relationship between creativity and urban transformation. it stems from the assumption that creativity has a para- doxical nature as it is simultaneously used for the production of the neoliberal city and by those seeking to challenge it and build alternative urban realities. first, we put forth a criti- cal review of the creative city narrative, focused on richard florida’s work, as it progres- sively became fundamental for the neoliberal city. afterwards, and contrasting with that dominant narrative, we describe a trajectory of Reclaim the Streets that provides the basis for our discussion of the protestival (protest + carnival) as its main creative force of urban transformation. Keywords: Creativity, urban transformation, Reclaim the Streets, protestival. Resumo – reclaiM the streets, o protestival e a transForMação criativa Da ciDaDe. O principal objetivo deste artigo é refletir sobre a relação existente entre criativi- dade e transformação urbana. Parte-se do princípio de que a criatividade tem uma natureza paradoxal, na medida em que é simultaneamente usada para a produção da cidade neolibe- ral, mas também por aqueles que procuram desafiá-la e construir realidades urbanas alter- nativas. Primeiro, fazemos uma revisão crítica da narrativa da cidade criativa, focada no trabalho de richard florida, por esta se ter progressivamente tornado fundamental para a cidade neoliberal. Depois, e contrastando com essa narrativa dominante, descrevemos uma trajetória do Reclaim the Streets que providencia a base para a nossa discussão do protesti- val (protesto + carnaval) como a sua principal força criativa de transformação urbana. -

Thoughts on Libertarian Municipalism

Thoughts on Libertarian Municipalism Murray Bookchin Age, chronic illnesses, and the summer heat oblige me to remain at home—hence I am very sorry that I cannot participate in your conference on libertarian municipalism. I would like, however— thanks to Janet Biehl, who will read these remarks—to welcome you to Vermont and to wish you well during the course of your discussions over the next three days. Some issues have recently arisen in discussions of libertarian municipalism, and I would like to offer my views on them. One of the most important involves the distinction that should be drawn between libertarian municipalism and communitarianism, a distinction that is often lost in discussions of politics. Communitarianism By communitarianism, I refer to movements and ideologies that seek to transform society by creating so-called alternative economic and living situations such as food cooperatives, health centers, schools, printing workshops, community centers, neighborhood farms, “squats,” unconventional lifestyles, and the like. Allowing for the works of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, the notable spokespersons of communitarianism have been Martin Buber, Harry Boyte, and Colin Ward, among many others. The word communitarian is often interchangeable with the word cooperative, a form of production and exchange that is attractive because the work is not only amiably collective but worker-controlled or worker-managed. At most, communitarianism seeks to gently edge social development away from privately owned enterprises—banks, corporations, supermarkets, factories, and industrial systems of agriculture —and the lifeways to which they give rise, into collectively owned enterprises and values. It does not seek to create a power center that will overthrow capitalism; it seeks rather to outbid it, outprice it, or outlast it, often by presenting a moral obstacle to the greed and evil that many find in a bourgeois economy. -

5 Almeida Street and 129 Upper Street, Islington Retail Impact Assessment 22 October 2008

5 Almeida Street and 129 Upper Street, Islington Retail Impact Assessment 22 October 2008 List of Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION 2.0 PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT 3.0 RETAIL POLICY CONTEXT 4.0 DEFINITION OF STUDY AREA 5.0 EXISTING CENTRES HEALTH CHECK 6.0 SHOPPING PATTERNS 7.0 QUANTITATIVE NEED, CAPACITY AND IMPACT 8.0 QUALITATIVE IMPACT ASSESSMENT 9.0 SEQUENTIAL SITE ASSESSMENT 10.0 CONCLUSION Annex 1: Angel Town Centre Retail Footprint Catchment Annex 2: Household Expenditure: Summary by COICOP Group Current Prices Annex 3: 2001 Census: Population Profile Annex 4: ACORN Profile - Households Annex 5: Proposed Scheme Impact Summary Annex 6: Proposed Scheme Net Gail on Angel Town Centre Annex 7: Retail Footprint London Rankings Annex 8: Proposed Scheme Retail Footprint Catchment Annex 9: Proposed Site Household Expenditure: Summary by COICOP Group Current Prices Annex 10: ACORN Shopper Profile – Households Annex 11: 2001 Census: Population Profile Annex 12: Sequential Test Site Locations 3 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 This report has been prepared in relation to a planning application to redevelop 5 Almeida Street, London N1, currently a mail facility and 129 Upper Street, formerly The Mitre Public House, submitted on behalf of Sager House (Almeida) Ltd. 1.2 This report presents key findings from a detailed evaluation of retail impact levels at the site. It follows a report by retail analysts CACI to Halpern Planning in 2004 to review the impact and market position of a scheme on the adjoining site, granted planning permission in 2007, using a combination of lifestyle data, expenditure models, gravity model simulation and benchmarking techniques. -

Historic Maps and Plans of Islington (1553-1894)

Mapping Islington Historic maps and plans of Islington (1553-1894) Mapping Islington showcases a selection of maps and plans relating to the three former historic parishes that now form the London Borough of Islington. Maps are a window into the past. They provide historical evidence and offer a valuable insight to bygone streets, industries and landscapes. They are also an important source for local history research and help us to understand the development and changes that have shaped the Plan of parish of St Mary, character and identity of our borough. Islington and its environs. Surveyed by Edward Baker The display’s earliest map dates from mid-16th Century (c.1793) when Islington was a rural village outside of the City of London, ending with a survey published during the late-Victorian era when the area had become a densely populated and urbanised district of north London. The London Borough of Islington was formed in 1965 when the Metropolitan boroughs of Islington and Finsbury merged. In 2019 the borough covers an area of 14.86 km2 and stretches from Highgate in the north to the City of London borders in the south. Before 1900 Islington was historically administered in three distinct civil parishes: • St Mary Islington (north and central) • St James Clerkenwell (south-west) • St Luke Old Street (south-east) The Copperplate Map of London, c.1553-59 Moorfields The Copperplate Map of London is a large-scale plan Frans Franken of the city and its immediate environs. It was originally Museum of London created in 15 printed copperplate sections, of which only three are still in existence. -

Reclaim the Streets, the Protestival and the Creative Transformation of the City

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Directory of Open Access Journals Finisterra, XLVii, 94, 2012, pp. 103-118103 RECLAIM THE STREETS, THE PROTESTIVAL aND THE CREaTiVE TRaNSFoRMaTioN oF THE CiTY anDré carMo1 abstract – the main goal of this article is to reflect upon the relationship between creativity and urban transformation. it stems from the assumption that creativity has a para- doxical nature as it is simultaneously used for the production of the neoliberal city and by those seeking to challenge it and build alternative urban realities. first, we put forth a criti- cal review of the creative city narrative, focused on richard florida’s work, as it progres- sively became fundamental for the neoliberal city. afterwards, and contrasting with that dominant narrative, we describe a trajectory of Reclaim the Streets that provides the basis for our discussion of the protestival (protest + carnival) as its main creative force of urban transformation. Keywords: Creativity, urban transformation, Reclaim the Streets, protestival. Resumo – reclaiM the streets, o protestival e a transForMação criativa Da ciDaDe. O principal objetivo deste artigo é refletir sobre a relação existente entre criativi- dade e transformação urbana. Parte-se do princípio de que a criatividade tem uma natureza paradoxal, na medida em que é simultaneamente usada para a produção da cidade neolibe- ral, mas também por aqueles que procuram desafiá-la e construir realidades urbanas alter- nativas. Primeiro, fazemos uma revisão crítica da narrativa da cidade criativa, focada no trabalho de richard florida, por esta se ter progressivamente tornado fundamental para a cidade neoliberal. -

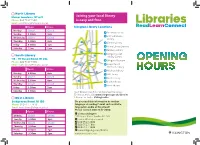

Joining Your Local Library Is Easy and Free

North Library Manor Gardens, N7 6JX Joining your local library Phone: 020 7527 7840 is easy and free. Email: [email protected] Opens Closes Islington Library Locations Monday Closed Closed 1 Archway Library Tuesday 9.30am 8pm 2 Cat and Mouse Wednesday Closed Closed Library Thursday 9.30am 8pm 3 Central Library Friday 9.30am 1pm 3 Home Library Service Saturday 11am 5pm 4 Finsbury Library 4 Islington Local South Library History Centre 115 - 117 Essex Road, N1 2SL 4 Islington Museum Phone: 020 7527 7860 Email: [email protected] 5 Lewis Carroll Children’s Library Opens Closes 6 Mildmay Library Monday 9.30am 8pm 7 N4 Library Tuesday Closed Closed 8 North Library Wednesday 9.30am 8pm 9 South Library Thursday Closed Closed 10 West Library Friday 9.30am 5pm Saturday 9.30am 5pm Most libraries have full or partial wheelchair access. To find out more, visit www.islington.gov.uk/libraries West Library Follow us on Twitter @islingtonlibs Bridgeman Road, N1 1BD Do you need this information in another Phone: 020 7527 7920 language or reading format such as Braille, Email: [email protected] large print, audio or Easy Read? Please contact 020 7527 2000. Opens Closes Contact Islington Monday Closed Closed 222 Upper Street London N1 1XR Tuesday 9.30am 8pm [email protected] Wednesday Closed Closed 020 7527 2000 020 7527 5001 Thursday 9.30am 8pm 020 7527 1900 Friday 9.30am 5pm www.islington.gov.uk/libraries Saturday 9.30am 5pm Published November 2017 Archway Library Finsbury Library Lewis Carroll Children’s Library -

Fully Let Prime London Investment Opportunity 21 & 29-31 Essex Road Islington, London N1 Investment Summary

FULLY LET PRIME LONDON INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY 21 & 29-31 ESSEX ROAD ISLINGTON, LONDON N1 INVESTMENT SUMMARY Located in Islington, one of the most affluent London Boroughs. Situated on Essex Road which benefits from a variety of pubs, bars, shops and restaurants whilst in close proximity to Islington Green, Upper Street and Angel Underground Station. Nearby occupiers include Tesco Express, Reiss, Waterstones, Côte Brasserie, The Gym Group, Nuffield Health & Fitness, Barrio, Wenlock & Essex and the Old Queens Head. Comprises two ground floor units held on two separate long leasehold interests at fixed peppercorn rents. Fully let to Brewdog (underlet to Essex House) and Floatworks producing a total rent passing of £190,000 per annum (any outstanding rent free and annual stepped rents to be topped up). Attractive Average Weighted Unexpired Lease Term of 14.7 years to expiry (11.6 years to break). Seeking offers of£3,244,000 (Three Million, Two Hundred and Forty Four Thousand Pounds), Subject to Contract and exclusive of VAT, reflecting aNet Initial Yield of 5.50%, allowing for purchaser’s costs of 6.48%. Situated on Essex Road which benefits from a variety of pubs, bars, shops and restaurants whilst in close proximity to Islington Green, Upper Street and Angel Underground Station. 21 & 29-31 ESSEX ROAD // ISLINGTON // LONDON N1 PRIME LONDON INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY 2 LOCATION SITUATION London Borough of Islington, one of London’s most vibrant and The subject property is prominently situated in the heart of Islington affluent conurbations, is located approximately 2 miles (3.2 km) north on the western side of Essex Road at its junction with Gaskin Street. -

The New Anarchists

A Movement of Movements?—5 david graeber THE NEW ANARCHISTS t’s hard to think of another time when there has been such a gulf between intellectuals and activists; between theorists of Irevolution and its practitioners. Writers who for years have been publishing essays that sound like position papers for vast social movements that do not in fact exist seem seized with confusion or worse, dismissive contempt, now that real ones are everywhere emerging. It’s particularly scandalous in the case of what’s still, for no particularly good reason, referred to as the ‘anti-globalization’ movement, one that has in a mere two or three years managed to transform completely the sense of historical possibilities for millions across the planet. This may be the result of sheer ignorance, or of relying on what might be gleaned from such overtly hostile sources as the New York Times; then again, most of what’s written even in progressive outlets seems largely to miss the point—or at least, rarely focuses on what participants in the movement really think is most important about it. As an anthropologist and active participant—particularly in the more radical, direct-action end of the movement—I may be able to clear up some common points of misunderstanding; but the news may not be gratefully received. Much of the hesitation, I suspect, lies in the reluc- tance of those who have long fancied themselves radicals of some sort to come to terms with the fact that they are really liberals: interested in expanding individual freedoms and pursuing social justice, but not in ways that would seriously challenge the existence of reigning institu- tions like capital or state. -

ISLINGTON News

ISSN 1465 - 9425 Winter 2004 ISLINGTON news The Journal of the ISLINGTON SOCIETY incorporating FOIL folio Saving Local Shops Section Break The Council’s development plans, and all the Islington Society’s campaigning for a sustainable environment, will fail unless we residents use our local shops, and learn to appreciate what an important part they play in the life of the community, writes Harley Sherlock . In 1997 the Islington Society, with others, won a only 30 percent of the shops. And the Council’s great victory over the Council and Sainsbury’s by Development Plan does indeed designate such defeating the latter’s proposals for an out-of-centre areas, which must be located so that everyone in superstore on the Lough Road site in Holloway. Islington “should be within easy reach” of essential There can be little doubt that such a store, being shops. It seems to me that this policy has worked mainly accessible only by car, would have increased reasonably well, and that without it we would by traffic in the area enormously; and, more now be considerably worse off than we actually are. importantly, it would have been the death-knell for But there can be no doubt that the planners’ good food-shopping at The Nags Head, Highbury Barn intentions will be brought to naught unless we, as and Caledonian Road, as well as for local residents, support them. neighbourhood shops generally. The abandonment So why don’t we? And why do so many of my of the superstore means that those of us living in fellow residents in Canonbury take the car to places the south of the borough, at least, have retained our like Brent Cross or Palmers Green when we have ability to walk to the shops rather than having to good-quality grocers, green-grocers, butchers, emulate the rest of the country by getting the car delicatessens and even a fish-monger within out every time we need an extra loaf of bread. -

A Premier Retail and Leisure Destination

A Premier Retail and Leisure Destination 1 2 3 A thriving neighbourhood Close to 1 million catchment and rising and premier retail and leisure Average household income £52K, higher than the London average destination for London Edmonton North Islington Square is a new destination for London in a unique Finchley A406 heritage setting; distinctly stylish, aspirational and full of character. A10 Finchley Wood Green Tottenham A London Square, composed of 170,000 sq ft of quality retail Muswell and leisure space, exceptional public realm and office space, Hill A105 A503 263 new homes, and 108 serviced apartments at the heart Walthamstow of one of London’s most affluent boroughs. An all-day leisure Harringay offer will include premium gym operator Third Space and a A1 Crouch End Stamford Golders Hill five-screen, The Lounge by Odeon luxury cinema. Finsbury Leytonstone Green Park Fonthill Stoke Leyton Road Newington Holloway Hampstead A12 A10 A41 Kentish Dalston Swiss Town Hackney Stratford Cottage Chalk A503 Islington Farm • Islington Camden Square Kilburn Town Roman Road Bow Bethnal Green A5 A501 A11 Islington Catchment Breakdown primary 123,000 secondary 282,000 tertiary 510,000 4 5 6 7 A new focal point £166m annual non-grocery shopper spend for Islington 11,000 office workers within a 10 minute walk Islington Square has been designed to reflect the vibrant community and rich heritage of this unique London Borough. = 1,000 As a truly mixed use development, Islington Square will enhance the location’s unique character and build on the timelessness and heritage of the Edwardian former Post Office building to become a hub for contemporary London living. -

Changing Anarchism.Pdf

Changing anarchism Changing anarchism Anarchist theory and practice in a global age edited by Jonathan Purkis and James Bowen Manchester University Press Manchester and New York distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave Copyright © Manchester University Press 2004 While copyright in the volume as a whole is vested in Manchester University Press, copyright in individual chapters belongs to their respective authors. This electronic version has been made freely available under a Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC- ND) licence, which permits non-commercial use, distribution and reproduction provided the author(s) and Manchester University Press are fully cited and no modifications or adaptations are made. Details of the licence can be viewed at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Published by Manchester University Press Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9NR, UK and Room 400, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for ISBN 0 7190 6694 8 hardback First published 2004 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Typeset in Sabon with Gill Sans display by Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Manchester Printed in Great Britain by CPI, Bath Dedicated to the memory of John Moore, who died suddenly while this book was in production. His lively, innovative and pioneering contributions to anarchist theory and practice will be greatly missed. -

Capitalist Movement

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by MURAL - Maynooth University Research Archive Library © Copyright Irish Journal of Sociology ISSN 0791 6035 Vol. 18.2, 2010, pp. 86–105 Revolution in the air: images of winning in the Irish anti- capitalist movement LAURENCE COX Department of Sociology, National University of Ireland, Maynooth LIZ CURRY Researcher, Dublin City University Abstract This article explores strategic conceptions within the alter-globalisation move- ment in Ireland. Based on action research carried out within the left-libertarian (“Grassroots’) wing of the movement, it notes imbalances in participation in a very intensive form of political activity, and asks how activists understand winning. It finds substantial congruence between organisational practice and long-term goals, noting social justice and participatory democracy along with feminist, environmental and anti-war concerns as central. Using Wallerstein’s proposed transition strategy for anti-systemic movements, it argues that Irish alter-globalisation activists are realistic about popular support and state power, and concerned to link short-term work around basic needs with the construction of alternative institutions and long-term struggles for a different social order. Key words: social movements, Ireland, alter-globalisation, anti-capitalism, strategy, utopia Introduction: alter-globalisation and Ireland In 2010, the worldwide alter-globalisation movement is fifteen years old, dating from the first Zapatista-sponsored Encuentros, which in turn gave rise to the People’s Global Action alliance that shut down the World Trade Organisation in Seattle in 1999 – since which point it has been unable to conclude a single trade round. Irish participants were first involved in the 2000 and 2001 protests in Prague and Genoa respectively, while 2002 saw the police discover that the media and other elites did not accept the licence they believed they had to attack participants of a Reclaim the Streets party in Dublin (Ní Dhorchaigh and Cox 2009).