Carnivals Against Capital: Radical Clowning and the Global Justice Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reclaim the Streets! from Local to Global Party Protest

THIRD TEXT Critical Perspectives on Contemporary Art and Culture July 2013 Reclaim The Streets! From Local to Global Party Protest Julia Ramírez Blanco If I can’t dance it’s not my revolution.1 Over the years, we have become used to experiencing works of art instead of merely watching them. As spectators, we are asked to become participants in what are considered to be artistic ‘situations’. The institutional and academic worlds propose terms such as ‘relational art’ or ‘community art’.2 A certain neo-situationist theoretical current introduces quotes of Guy Debord, Jean Baudrillard, Raoul Vaneigem and Michel de Certeau into the texts that deal with these practices. In considering these developments, Claire Bishop has spoken of a ‘social turn’ in contemporary art. However, in the introduction to her book Artificial Hells (2012), she states that this might actually be a return, and that such a return belongs to a certain tradition: From a Western European perspective, the social turn in contemporary art can be contextualized by two previous historical moments, both synonymous with political upheaval and movements for social change: the historic avant-garde in Europe circa 1917, and the so-called ‘neo’ avant-garde leading to 1968. The conspicuous resurgence of participatory art in the 1990s leads me to posit the fall of communism in 1989 as a third point of transformation. Triangulated, these three dates form a narrative of the triumph, heroic last stand and collapse of a collectivist vision of society. Each phase has been accompanied by a utopian rethinking of art’s relationship to the social and of its political potential – manifested in a reconsideration of the ways in which art is produced, consumed and debated.3 As had happened with previous explosions of participation in the art field, the renewed interest in participation of the 1990s cannot be fully understood without looking at what was happening at the same time in the field of activism. -

Behind the Masks, the Politics of Carnival

INTRODUCTION Behind the Masks, The Politics of Carnival Aurélie Godet Université de Paris, France 1. Baron Joseph X. Pontalba, “The ladies, on one side, found pleasure in knotting my bed sheets together, in throwing water letter to his wife, October 15, 1796, at me … while I, on the other, smudged their bed clothes with lamp-black, so that they became WPA trans., typescript, Louisiana State University Library, Baton smeared all over with it; I inserted an apothecary drug, one with a subtle scent, into their pillows; I Rouge, 358. squirted water at them with a syringe; I dropped bits of wood down their chimneys at night, made holes in the chamber pots, etc.” 2. Donald Cosentino, “‘My Heart Don’t Stop’: Haiti, the Carnival Baron Joseph X. Pontalba, describing a party at Louis Barthélémy de Macarty’s plantation house State,” in Carnaval!, ed. Barbara 1 Mauldin (Seattle: University of during the 1796 yellow fever epidemic in New Orleans Washington Press/Santa Fe: Museum of International Folk Art, 2004), 285. 3. Anne Schuchat, “Public Health “In this new age of pandemics and holy wars, it felt good to be there, bottoming out, looking at Response to the Initiation and the world from upside-down.” Spread of Pandemic COVID-19 in the United States, February Donald Cosentino, about Haitian Carnival in the wake of the AIDS epidemic2 24–April 21, 2020,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, US Department of Health and Human Services, May 8, 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/vol- A Note on Festivity and the Current Pandemic umes/69/wr/mm6918e2.htm. -

This Index Can Also Serve As a Glossary. Page References Set In

Autonomous communities convergence centres, 215; 448; unmasking of, 309, 310, 499; see also Neoliberalism, Index Kuna, 113; Mendha, India, 115; Mentawi Islands, 115; Economic globalization Pak Mun Protest Villages 140; piqueteros, 472-481; Cargill (dismantled) 160 This index can also serve as a glossary. San Salvador Atenco, 473; social centres, 425; Carnival [174], 173-183, 346 as counterpower, 350; as Page references set in brackets indicate definition Village Republic, 155; Zapatistas, 80, 114 spectacle, 26, 176; as ‘terrorism’, 179; creating space for, or thorough treatment of a topic. Autonomy [107-109], 107-119 and piqueteros, 475; 224; goals, 175; in Ogoniland, 196; and music, 216 Please note that the timeline is not indexed. and Peoples’ Global Action, 96; and sans-papiers, 40; Carnivals against capital and the FBI, 179; in London, appeal of, 108; appropriation of, 108; 184-187, 188-195, 217, 231; in Prague, 290-295; in Québec confused with independence and individualism, 109; City, 178, 346; in Seattle, 174 development of, 423; essential components, 112; Democracy (charade of) 474 in affinity groups, 215; in economies see also US presidential elections A see Solidarity economy Chase Manhattan Bank 310 Acteal massacre 82, 89 Chiapas autonomy in, 114-155; clandestinity in, 306; Active Resistance 231 inspiration from, 397; perceived threat, 310; poverty and Affinity groups [60], 67, 191, [202-203], 215, 312, 375 B violence in, 80-87; see also Zapatistas Agribusiness 152 Baboon butt 252 City of London 176, 188 protest in, 196, 176, -

Carnival Resistance Is the Secret of Joy

Carnival resistance is the secret of joy “The goal of the revolutionary artist is to make sidewalks, a cacophony of colour and exhilaration. revolution irresistible.” – Toni Cade Bambara Sleeplessness didn’t matter anymore. We passed a tripod blockade, a man dangling from its apex, a line of cars “We will make revolution irresistible,” assured a bit of immobilized impatiently, not yet understanding how Direct Action Network propaganda in the final days of futile they were that day. Those were the last cars I saw November 1999. Writing those words late at night, I was for 12 hours. hunched on the floor of the near-empty warehouse in As we entered downtown something shifted. It was downtown Seattle with a friend and a laptop, with only 30 partially the fresh air blowing off the Puget Sound, minutes before going to print, and eight hours before we unpolluted by the choking exhaust that was the normal opened the convergence centre – a networking hub and scent of the city. We controlled the streets, all of them, training facility for activists – to the world. After having and in every direction we looked were more and more of gone for months with too much to do and too little sleep, I us, and thousands still arriving. There were stilt walkers grumbled about how utterly resistible this particular dressed as butterflies, a giant inflatable whale blockading aspect of ‘revolution’ seemed, before getting on my bike an intersection, a hip hop crew rhyming through a mobile and weaving my way home – to yet another meeting. sound system, a stage being built to double as a road Organizing a Festival of Resistance didn’t feel particularly blockade where performances would take place all day festive that night. -

London: a Capital of Protest Politics

Observatoire de la société britannique 11 (2011) Londres : capitale internationale, multiculturelle et olympique ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ Jeremy Tranmer London: a capital of protest politics ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ Avertissement Le contenu de ce site relève de la législation française sur la propriété intellectuelle et est la propriété exclusive de l'éditeur. Les œuvres figurant sur ce site peuvent être consultées et reproduites sur un support papier ou numérique sous réserve qu'elles soient strictement réservées à un usage soit personnel, soit scientifique ou pédagogique excluant toute exploitation commerciale. La reproduction devra obligatoirement mentionner l'éditeur, le nom de la revue, l'auteur et la référence du document. Toute autre reproduction est interdite sauf accord préalable de l'éditeur, en dehors des cas prévus par la législation en vigueur en France. Revues.org est un portail de revues en sciences humaines et sociales développé par le Cléo, Centre pour l'édition électronique ouverte (CNRS, EHESS, UP, -

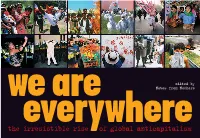

The Irresistible Rise of Global Anticapitalism for Struggling for a Better World All of Us Are Fenced In, Threatened with Death

edited by we are Notes from Nowhere everywhere the irresistible rise of global anticapitalism For struggling for a better world all of us are fenced in, threatened with death. The fence is reproduced globally. In every continent, every city, every countryside, every house. Power’s fence of war closes in on the rebels, for whom humanity is always grateful. But fences are broken. The rebels, whom history repeatedly has given the length of its long trajectory, struggle and the fence is broken. The rebels search each other out. They walk toward one another. They find each other and together break other fences. First published by Verso 2003 The texts in this book are copyleft (except where indicated). The © All text copyleft for non-profit purposes authors and publishers permit others to copy, distribute, display, quote, and create derivative works based upon them in print and electronic 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 format for any non-commercial, non-profit purposes, on the conditions that the original author is credited, We Are Everywhere is cited as a source Verso along with our website address, and the work is reproduced in the spirit of UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG the original. The editors would like to be informed of any copies produced. USA: 180 Varick Street, New York, NY 10014-4606 Reproduction of the texts for commercial purposes is prohibited www.versobooks.com without express permission from the Notes from Nowhere editorial collective and the publishers. All works produced for both commercial Verso is the imprint of New Left Books and non-commercial purposes must give similar rights and reproduce the copyleft clause within the publication. -

Revealing Power: Masked Protest and the Public Sphere

Revealing power: masked protest and the public sphere Article (Accepted Version) Ruiz, Pollyanna (2013) Revealing power: masked protest and the public sphere. Cultural Politics, 9 (3). pp. 263-279. ISSN 1743-2197 This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/51878/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk This is the author’s final version. The version of record may be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1215/17432197-2346973. -

Proof Cover Sheet

PROOF COVER SHEET Author(s): Stephen E. Hunt Article title: The Echoing Greens: The Neo-Romanticism of Earth First! and Reclaim The Streets in the U.K. Article no: RCNS 784526 Enclosures: 1) Query sheet 2) Article proofs Dear Author, 1. Please check these proofs carefully. It is the responsibility of the corresponding author to check these and approve or amend them. A second proof is not normally provided. Taylor & Francis cannot be held responsible for uncorrected errors, even if introduced during the production process. Once your corrections have been added to the article, it will be considered ready for publication. Please limit changes at this stage to the correction of errors. You should not make insignificant changes, improve prose style, add new material, or delete existing material at this stage. Making a large number of small, non-essential corrections can lead to errors being introduced. We therefore reserve the right not to make such corrections. For detailed guidance on how to check your proofs, please see http://journalauthors.tandf.co.uk/production/checkingproofs.asp. 2. Please review the table of contributors below and confirm that the first and last names are structured correctly and that the authors are listed in the correct order of contribution. This check is to ensure that your name will appear correctly online and when the article is indexed. Sequence Prefix Given name(s) Surname Suffix 1 Stephen E. Hunt Queries are marked in the margins of the proofs. AUTHOR QUERIES General query: You have warranted that you have secured the necessary written permission from the appropriate copyright owner for the reproduction of any text, illustration, or other material in your article. -

Media Mccurdy W Pictures

The London School of Economics and Political Science ‘I Predict a Riot’ – Mediation and Political Contention: Dissent!’s media practices at the 2005 Gleneagles G8 Summit Patrick M. McCurdy A thesis submitted to the Department of Media and Communications of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, March 2009. 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of the author. I warrant that this authorization does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. 2 Abstract International meetings such as the G8 Summit have evolved from the sequestered gatherings of the economic elite to full-scale political media events. Using the 2005 Gleneagles G8 Summit as a case study, and focusing on one specific ‘autonomous’ activist network – Dissent! – this thesis investigates how the process of mediation is articulated in activists’ practices in preparing and enacting acts of contention. Dominant approaches to such events in the field of media and communications are often text-centred, focussing on the media’s framing of protest, overlooking the actions against and interactions with the media at such sites. -

Festivals of Art, Carnivals of Representation: on Contemporary Art and Neoliberalism Tijen Tunali

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Art & Art History ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-1-2015 Festivals of Art, Carnivals of Representation: On Contemporary Art and Neoliberalism Tijen Tunali Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/arth_etds Recommended Citation Tunali, Tijen. "Festivals of Art, Carnivals of Representation: On Contemporary Art and Neoliberalism." (2015). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/arth_etds/4 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art & Art History ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. , Tijen Tunalı Candidate Art and Art History Department Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: David L. Craven, Ph.D.,Chairperson Olivia L. Lumpkin, Ph.D., Chairperson Eleni Bastea, Ph.D. Kency Cornejo, Ph.D. Linda B. Hall, Ph.D. Catherine Zuromskis, Ph.D. i FESTIVALS OF ART, CARNIVALS OF REPRESENTATION: ON CONTEMPORARY ART AND NEOLIBERALISM BY TIJEN TUNALI B.S., Economics, University of Istanbul, 1996 B.A., Fine Arts, SUNY at Binghamton, 2004 M.A. Visual Studies and the New Media, SUNY at Buffalo, 2006 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Art History The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico December 2015 ii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to the memory of my advisor Dr. David Craven (1952- 2012), who left behind many inspired students that will continue his legacy. -

Social Media, Politics and the State

Social Media, Politics and the State This book is the essential guide for understanding how state power and politics are contested and exercised on social media. It brings together con- tributions by social media scholars who explore the connection of social media with revolutions, uprising, protests, power and counter-power, hack- tivism, the state, policing and surveillance. It shows how collective action and state power are related and conflict as two dialectical sides of social media power, and how power and counter-power are distributed in this dialectic. Theoretically focused and empirically rigorous research considers the two-sided contradictory nature of power in relation to social media and politics. Chapters cover social media in the context of phenomena such as contemporary revolutions in Egypt and other countries, populism 2.0, anti- austerity protests, the fascist movement in Greece’s crisis, Anonymous and police surveillance. Daniel Trottier is a postdoctoral fellow in social and digital media at the Communication and Media Research Institute (CAMRI) at the University of Westminster. Christian Fuchs is a professor of social media at the University of Westminster. Routledge Research in Information Technology and Society 1 Reinventing Government 8 Internet and Society in the Information Age Social Theory in the International Practice in Information Age IT-Enabled Public Sector Reform Christian Fuchs Edited by Richard Heeks 9 Hacking Capitalism 2 Information Technology The Free and Open Source in Government Software Movement Britain and America Johan Söderberg Helen Margetts 10 Urban Youth in China: 3 Information Society Studies Modernity, the Internet and Alistair S. Duff the Self Fengshu Liu 4 National Electronic Government Building an Institutional 11 Network Governance Framework for Joined Up of Global Religions Government—A Comparative Jerusalem, Rome, and Mecca Study Michel S. -

In the Footnotes of Library Angels: a Bi(Bli)Ography of Insurrectionary Imagination (2006)

LADA Study Room Guides As part of the continuous development of the Study Room we regularly commission artists and thinkers to write personal Study Room Guides on specifc themes. The idea is to help navigate Study Room users through the resource, enable them to experience the materials in a new way and highlight materials that they may not have otherwise come across. All Study Room Guides are available to view in our Study Room, or can be viewed and/or downloaded directly from their Study Room catalogue entry. Please note that materials in the Study Room are continually being acquired and updated. For details of related titles acquired since the publication of this Guide search the online Study Room catalogue with relevant keywords and use the advance search function to further search by category and date. Cover image credit: The Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination, The People v the Banksters snowball fght, 2009. Photographer Kristian Buss In the Footnotes of Library Angels: A Bi(bli)ography of Insurrectionary Imagination (2006) Dear Reader Before we begin on this journey in search of words and images that speak of the insurrectionary imagination1; Before we bend those fragile spines and flick through brittle pages to reveal moments where the spirit of art2 and activism merge3; Before we drift4 through these words, fingering paper, armed with footnotes5 guiding our steps across this library. I want to ask you a question - Do you believe in Library Angels? 1 The Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination (lab of ii) was founded in 2004 by myself, the artists activist, The Vacuum cleaner ( see his DVD - The Vacuum Cleaner, Anti Adverts, 2003 ref: D0180) and radical educator Isabelle Fremeaux.