Exploring Dialogic Social Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By Patrick James Barry a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of The

CONFIRMATION BIAS: STAGED STORYTELLING IN SUPREME COURT CONFIRMATION HEARINGS by Patrick James Barry A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Professor Enoch Brater, Chair Associate Professor Martha Jones Professor Sidonie Smith Emeritus Professor James Boyd White TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 SITES OF THEATRICALITY 1 CHAPTER 2 SITES OF STORYTELLING 32 CHAPTER 3 THE TAUNTING OF AMERICA: THE SUPREME COURT CONFIRMATION HEARING OF ROBERT BORK 55 CHAPTER 4 POISON IN THE EAR: THE SUPREME COURT CONFIRMATION HEARING OF CLARENCE THOMAS 82 CHAPTER 5 THE WISE LATINA: THE SUPREME COURT CONFIRMATION HEARING OF SONIA SOTOMAYOR 112 CHAPTER 6 CONCLUSION: CONFIRMATION CRITIQUE 141 WORK CITED 166 ii CHAPTER 1 SITES OF THEATRICALITY The theater is a place where a nation thinks in public in front of itself. --Martin Esslin, An Anatomy of Drama (1977)1 The Supreme Court confirmation process—once a largely behind-the-scenes affair—has lately moved front-and-center onto the public stage. --Laurence Tribe, Advice and Consent (1992)2 I. In 1975 Milner Ball, then a law professor at the University of Georgia, published an article in the Stanford Law Review called “The Play’s the Thing: An Unscientific Reflection on Trials Under the Rubric of Theater.” In it, Ball argued that by looking at the actions that take place in a courtroom as a “type of theater,” we might better understand the nature of these actions and “thereby make a small contribution to an understanding of the role of law in our society.”3 At the time, Ball’s view that courtroom action had an important “theatrical quality”4 was a minority position, even a 1 Esslin, Martin. -

Issue: Fashion Industry Fashion Industry

Issue: Fashion Industry Fashion Industry By: Vickie Elmer Pub. Date: January 16, 2017 Access Date: October 1, 2021 DOI: 10.1177/237455680302.n1 Source URL: http://businessresearcher.sagepub.com/sbr-1863-101702-2766972/20170116/fashion-industry ©2021 SAGE Publishing, Inc. All Rights Reserved. ©2021 SAGE Publishing, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Can it adapt to changing times? Executive Summary The global fashion business is going through a period of intense change and competition, with disruption coming in many colors: global online marketplaces, slower growth, more startups and consumers who now seem bored by what once excited them. Many U.S. shoppers have grown tired of buying Prada and Chanel suits and prefer to spend their money on experiences rather than clothes. Questions about fashion companies’ labor and environmental practices are leading to new policies, although some critics remain unconvinced. Fashion still relies on creativity, innovation and consumer attention, some of which comes from technology and some from celebrities. Here are some key takeaways: High-fashion brands must now compete with “fast fashion,” apparel sold on eBay and vintage sites. Risk factors for fashion companies include China’s growth slowdown, reduced global trade, Brexit, terrorist attacks and erratic commodity prices. Plus-size women are a growing segment of the market, yet critics say designers are ignoring them. Overview José Neves launched Farfetch during the global economic crisis of 2008, drawing more on his background in IT and software than a love of fashion. His idea: Allow small designers and fashion shops to sell their wares worldwide on a single online marketplace. The site will “fetch” fashion from far-off places. -

Culture Jamming

Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank Vincent de Jong for introducing me to the intricacy of the easyCity action, and for taking the time to answer my questions along my exploration of the case. I also want to thank Robin van t’ Haar for his surprising, and unique, contribution to my investigations of the easyCity action. Rozalinda Borcila, the insights you have shared with me have been a crucial reminder of my own privilieged position – your reflections, I hope, also became a marker in what I have written. Also, I would like to thank others that somehow made my fieldwork possible, and influenced my ‘learning’ of activism and culture jamming. Of these I would especially like to thank Nina Haukeland for introducing me to the politics of activism, Kirsti Hyldmo for reminding me of the realities of exploitation, Åse Brandvold for a skilled introduction to the thoughts and tools of culture jamming, and Maria Astrup for showing me the pleasures and powers of aesthetics. Also, I would like to thank the Norwegian Adbusters Network, and the editorial groups of Vreng. To my main advisor Professor Kristian Stokke, I would like to thank you for the excellent support you have given me throughout my master studies. Your insights have been of grate value, and I cannot thank you enough for continually challenging me. Also, the feedback from Olve Krange, my second advisor, was crucial at the early stage of developing the thesis, to defining its object of inquiry, and finally when writing my conclusion. I would also like to express my appreciation to Professor Oddrun Sæther for an excellent introduction to the field of cultural studies, to Professor Matt Sparke at the University of Washington for demonstrating the intriguing complexities of political geography, and to PhD candidate Stephen Young, for proof reading and fruitful inputs at the final stage of writing. -

'Perfect Fit': Industrial Strategies, Textual Negotiations and Celebrity

‘Perfect Fit’: Industrial Strategies, Textual Negotiations and Celebrity Culture in Fashion Television Helen Warner Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) University of East Anglia School of Film and Television Studies Submitted July 2010 ©This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that no quotation from the thesis, nor any information derived therefrom, may be published without the author's prior, written consent. Helen Warner P a g e | 2 ABSTRACT According to the head of the American Costume Designers‟ Guild, Deborah Nadoolman Landis, fashion is emphatically „not costume‟. However, if this is the case, how do we approach costume in a television show like Sex and the City (1998-2004), which we know (via press articles and various other extra-textual materials) to be comprised of designer clothes? Once onscreen, are the clothes in Sex and the City to be interpreted as „costume‟, rather than „fashion‟? To be sure, it is important to tease out precise definitions of key terms, but to position fashion as the antithesis of costume is reductive. Landis‟ claim is based on the assumption that the purpose of costume is to tell a story. She thereby neglects to acknowledge that the audience may read certain costumes as fashion - which exists in a framework of discourses that can be located beyond the text. This is particularly relevant with regard to contemporary US television which, according to press reports, has witnessed an emergence of „fashion programming‟ - fictional programming with a narrative focus on fashion. -

Re:Imagining Change

WHERE IMAGINATION BUILDS POWER RE:IMAGINING CHANGE How to use story-based strategy to win campaigns, build movements, and change the world by Patrick Reinsborough & Doyle Canning 1ST EDITION Advance Praise for Re:Imagining Change “Re:Imagining Change is a one-of-a-kind essential resource for everyone who is thinking big, challenging the powers-that-be and working hard to make a better world from the ground up. is innovative book provides the tools, analysis, and inspiration to help activists everywhere be more effective, creative and strategic. is handbook is like rocket fuel for your social change imagination.” ~Antonia Juhasz, author of e Tyranny of Oil: e World’s Most Powerful Industry and What We Must Do To Stop It and e Bush Agenda: Invading the World, One Economy at a Time “We are surrounded and shaped by stories every day—sometimes for bet- ter, sometimes for worse. But what Doyle Canning and Patrick Reinsbor- ough point out is a beautiful and powerful truth: that we are all storytellers too. Armed with the right narrative tools, activists can not only open the world’s eyes to injustice, but feed the desire for a better world. Re:Imagining Change is a powerful weapon for a more democratic, creative and hopeful future.” ~Raj Patel, author of Stuffed & Starved and e Value of Nothing: How to Reshape Market Society and Redefine Democracy “Yo Organizers! Stop what you are doing for a couple hours and soak up this book! We know the importance of smart “issue framing.” But Re:Imagining Change will move our organizing further as we connect to the powerful narrative stories and memes of our culture.” ~ Chuck Collins, Institute for Policy Studies, author of e Economic Meltdown Funnies and other books on economic inequality “Politics is as much about who controls meanings as it is about who holds public office and sits in office suites. -

Fashion and the First Ladies”

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: NEW YORK WOMEN IN FILM & TELEVISION AND FASHION GROUP INTERNATIONAL PRESENT “FASHION AND THE FIRST LADIES” An in-depth look at fashion as a communication tool throughout history and politics in celebration of Women’s History Month NEW YORK, NY – March 8, 2021 – New York Women in Film & Television (NYWIFT) and the Fashion Group International (FGI) are proud to present “Fashion and the First Ladies” on Friday, March 12, 2021 at 1 PM EST in celebration of Women’s History Month! In this hour-long virtual program, industry leaders Fernando Garcia (Co-Creative Director of Oscar De La Renta), Valerie Steele (Director and Chief Curator of The Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology), and Carson Poplin (Fashion Historian) will discuss the iconic looks from U.S. First Ladies of government in a candid conversation about how our First Ladies are fashion trend setters. The panel will explore how fashion plays a role and communicates in history, politics and contributes to the making or breaking of public policy. Archival images and current looks from recent First Ladies dressed by Oscar de la Renta will be featured. The conversation will be moderated by The Washington Post Senior Critic at Large, Robin Givhan. “The U.S. First Ladies have been at the forefront of social change, from Abigail Adams’s declaration to ‘remember the ladies’ to Michelle Obama’s advocacy for public health and education – and their fashion choices often played a critical role in establishing their personality, their message, and their power. NYWIFT is thrilled to dive deep into the role fashion plays in media and communications as we celebrate Women’s History – this month and every month,” said NYWIFT Executive Director Cynthia Lopez. -

Congressional Overspeech

ARTICLES CONGRESSIONAL OVERSPEECH Josh Chafetz* Political theater. Spectacle. Circus. Reality show. We are constantly told that, whatever good congressional oversight is, it certainly is not those things. Observers and participants across the ideological and partisan spectrums use those descriptions as pejorative attempts to delegitimize oversight conducted by their political opponents or as cautions to their own allies of what is to be avoided. Real oversight, on this consensus view, is about fact-finding, not about performing for an audience. As a result, when oversight is done right, it is both civil and consensus-building. While plenty of oversight activity does indeed involve bipartisan attempts to collect information and use that information to craft policy, this Article seeks to excavate and theorize a different way of using oversight tools, a way that focuses primarily on their use as a mechanism of public communication. I refer to such uses as congressional overspeech. After briefly describing the authority, tools and methods, and consensus understanding of oversight in Part I, this Article turns to an analysis of overspeech in Part II. The three central features of overspeech are its communicativity, its performativity, and its divisiveness, and each of these is analyzed in some detail. Finally, Part III offers two detailed case studies of overspeech: the Senate Munitions Inquiry of the mid-1930s and the McCarthy and Army-McCarthy Hearings of the early 1950s. These case studies not only demonstrate the dynamics of overspeech in action but also illustrate that overspeech is both continuous across and adaptive to different media environments. Moreover, the case studies illustrate that overspeech can be used in the service of normatively good, normatively bad, and * Professor of Law, Georgetown University Law Center. -

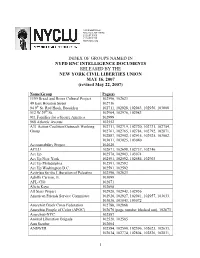

Index of Political Groups Mentioned in the Intelligence Documents

125 Broad Street New York, NY 10004 212.607.3300 212.607.3318 www.nyclu.org INDEX OF GROUPS NAMED IN NYPD RNC INTELLIGENCE DOCUMENTS RELEASED BY THE NEW YORK CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION MAY 16, 2007 (revised May 22, 2007) Name/Group Page(s) 1199 Bread and Roses Cultural Project 102596, 102623 49 East Houston Street 102716 94 9th St. Red Hook, Brooklyn 102711, 102928, 102943, 102956, 103008 512 W 29th St. 102964, 102976, 102983 911 Families for a Secure America 102999 968 Atlantic Avenue 102552 A31 Action Coalition/Outreach Working 102711, 102719, 102720, 102731, 102754, Group 102761, 102765, 102784, 102792, 102871, 102887, 102902, 102915, 102925, 103002, 103011, 103025, 103040 Accountability Project 102620 ACLU 102671, 102698, 102737, 102746 Act Up 102578, 102903, 103074 Act Up New York 102591, 102592, 102684, 102903 Act Up Philadelphia 102591, 102592 Act Up Washington D.C. 102591, 102592 Activists for the Liberation of Palestine 102596, 102623 Adolfo Carrion, Jr. 103099 AFL-CIO 102671 Alicia Keys 102698 All Stars Project 102928, 102943, 102956 American Friends Service Committee 102920, 102927, 102941, 102957, 103033, 103036, 103043, 103072 Anarchist Black Cross Federation 102788, 102868 Anarchist People of Color (APOC) 102670 (page number blacked out), 102673 Anarchist-NYC 102587 Animal Liberation Brigade 102520, 102585 Ann Stauber 102604 ANSWER 102584, 102590, 102596, 102623, 102633, 102634, 102774, 102804, 102826, 102831, 1 102843, 102884, 102900, 102906, 102916, 102919, 102926, 102940, 102952, 102959, 103068, 103076, 103092, 103096 Anthony -

Dead Kennedys and the Yippie-Punk Continuum I Michael Stewart Foley

Political Pie-Throwing: Dead Kennedys and the Yippie-Punk Continuum i Michael Stewart Foley To cite this version: Michael Stewart Foley. Political Pie-Throwing: Dead Kennedys and the Yippie-Punk Continuum i. Sonic Politics: Music and Social Movements in the Americas, 2019, 1138389390. hal-01999010 HAL Id: hal-01999010 https://hal.univ-grenoble-alpes.fr/hal-01999010 Submitted on 30 Jan 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Political Pie-Throwing: Dead Kennedys and the Yippie-Punk Continuumi MICHAEL STEWART FOLEY By the time Dead Kennedys released their first LP, Fresh Fruit for Rotting Vegetables, in 1980, the band had established itself as the leading American political punk band, hailing from a city that seemed to specialize in political art. In many ways, the band and its music represented the culmination of nearly three years of subcultural political struggle on a host of issues facing not only young people in San Francisco but American youth everywhere – enough that, to this day, many of the city’s punk veterans refer to their experience in the “movement.” Political historians of the United States in the 1970s and 1980s have mostly ignored punk, but this essay examines Dead Kennedys’ early career as a way to illuminate the political experience of one segment of American youth in the late 1970s. -

Gregory Sholette

GREGORY SHOLETTE Clearly the response by artists and academics to public events was far more direct and confrontational in the not-so-distant past than today. On May 2, 1970, members of the Art Workers Coalition and Guerrilla Art Action Group staged a mock gun battle in front of the Museum of Modern Art, and in 1976 a group of art historians and artists produced an anti-catalog denouncing the nationalism and racism of the bicentennial exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art. As late as the early 1980s, members of Group Material collaborated with an El Salvadorian support group to curate an exhibition opposed to United States pol- icy in Central America for a popular dance club, and the collective Political Art Documentation/Distribution paraded a blue, blimp-like Pac Man with the fea- tures of Uncle Sam in front of the White House. Militant street theater, inter- ventionist scholarship, activist curating, artists directly challenging their own well- being by denouncing museums and the art market—all of this appears inconceivable today. Perhaps the last artist-organized cultural campaign aimed at mass-mobilization in the United States was Artists Call Against Intervention in Central America in the mid-1980s. Organized primarily in New York City by veter- ans of the 1960s such as Leon Golub and Lucy Lippard (as well as younger organizers such as Doug Ashford of Group Material), Artists Call brought together younger artists, alternative spaces, small commercial dealers, and even a few major art galleries. Skillful organizing convinced these varied cultural partici- pants that acting to oppose U.S. -

Fashion Design in the 21St Century A

TECHNOLOGY AND CREATIVITY: FASHION DESIGN IN THE 21 ST CENTURY A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by MARY RUPPERT-STROESCU Dr. Jana Hawley, Dissertation Supervisor May 2009 © Copyright by Mary Ruppert-Stroescu 2009 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled TECHNOLOGY AND CREATIVITY: FASHION DESIGN IN THE 21 ST CENTURY Presented by Mary Ruppert-Stroescu, a candidate for the degree of doctor of philosophy and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. _______________________________ Dr. Kitty Dickerson _______________________________ Dr. Jana Hawley _______________________________ Dr. Laurel Wilson _______________________________ Dr. Julie Caplow I dedicate this dissertation to my sons, Matei and Ioan Stroescu, who are continuous sources of inspiration and joy. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my dissertation supervisor, Dr. Jana Hawley, for inspiring and challenging me without fail. I will remain eternally grateful as well to Dr. Laurel Wilson & Dr. Kitty Dickerson, for their patience, insight, and guidance. I must also recognize Dr. Jean Hamilton, whose courses I will never forget because her ability to communicate a passion for research sparked my path to this dissertation. Dr. Julie Caplow built upon the appreciation for qualitative research that began with Dr. Hamilton, and I thank her for her support. Without Peter Carman I would not have had a platform for connecting with the French industry interviewees. I thank my family for their support, and all those who took time from their professional obligations to discuss technology and creativity with me. -

Branding the Iconic Ideals of Vivienne Westwood, Barack Obama, and Pope Francis

PUNK, OBAMACARE, AND A JESUIT: BRANDING THE ICONIC IDEALS OF VIVIENNE WESTWOOD, BARACK OBAMA, AND POPE FRANCIS AIDAN MOIR A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN COMMUNICATION & CULTURE YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO April 2021 © Aidan Moir, 2021 Abstract Practices of branding, promotion, and persona have become dominant influences structuring identity formation in popular culture. Creating an iconic brand identity is now an essential practice required for politicians, celebrities, global leaders, and other public figures to establish their image within a competitive media landscape shaped by consumer society. This dissertation analyzes the construction and circulation of Vivienne Westwood, Barack Obama, and Pope Francis as iconic brand identities in contemporary media and consumer culture. The content analysis and close textual analysis of select media coverage and other relevant material on key moments, events, and cultural texts associated with each figure deconstructs the media representation of Westwood, Obama, and Pope Francis. The brand identities of Westwood, Pope Francis, and Obama ultimately exhibit a unique form of iconic symbolic power, and exploring the complex dynamics shaping their public image demonstrates how they have achieved and maintained positions of authority. Although Westwood, Obama, and Pope Francis initially were each positioned as outsiders to the institutions of fashion, politics, and religion that they now represent, the media played a key role in mainstreaming their image for public consumption. Their iconic brand identities symbolize the influence of consumption in shaping how issues of public good circulate within public discourse, particularly in regard to the economy, health care, social inequality, and the environment.