The Politics of Vision, Visibility, and Visuality in Vogue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By Patrick James Barry a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of The

CONFIRMATION BIAS: STAGED STORYTELLING IN SUPREME COURT CONFIRMATION HEARINGS by Patrick James Barry A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Professor Enoch Brater, Chair Associate Professor Martha Jones Professor Sidonie Smith Emeritus Professor James Boyd White TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 SITES OF THEATRICALITY 1 CHAPTER 2 SITES OF STORYTELLING 32 CHAPTER 3 THE TAUNTING OF AMERICA: THE SUPREME COURT CONFIRMATION HEARING OF ROBERT BORK 55 CHAPTER 4 POISON IN THE EAR: THE SUPREME COURT CONFIRMATION HEARING OF CLARENCE THOMAS 82 CHAPTER 5 THE WISE LATINA: THE SUPREME COURT CONFIRMATION HEARING OF SONIA SOTOMAYOR 112 CHAPTER 6 CONCLUSION: CONFIRMATION CRITIQUE 141 WORK CITED 166 ii CHAPTER 1 SITES OF THEATRICALITY The theater is a place where a nation thinks in public in front of itself. --Martin Esslin, An Anatomy of Drama (1977)1 The Supreme Court confirmation process—once a largely behind-the-scenes affair—has lately moved front-and-center onto the public stage. --Laurence Tribe, Advice and Consent (1992)2 I. In 1975 Milner Ball, then a law professor at the University of Georgia, published an article in the Stanford Law Review called “The Play’s the Thing: An Unscientific Reflection on Trials Under the Rubric of Theater.” In it, Ball argued that by looking at the actions that take place in a courtroom as a “type of theater,” we might better understand the nature of these actions and “thereby make a small contribution to an understanding of the role of law in our society.”3 At the time, Ball’s view that courtroom action had an important “theatrical quality”4 was a minority position, even a 1 Esslin, Martin. -

Issue: Fashion Industry Fashion Industry

Issue: Fashion Industry Fashion Industry By: Vickie Elmer Pub. Date: January 16, 2017 Access Date: October 1, 2021 DOI: 10.1177/237455680302.n1 Source URL: http://businessresearcher.sagepub.com/sbr-1863-101702-2766972/20170116/fashion-industry ©2021 SAGE Publishing, Inc. All Rights Reserved. ©2021 SAGE Publishing, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Can it adapt to changing times? Executive Summary The global fashion business is going through a period of intense change and competition, with disruption coming in many colors: global online marketplaces, slower growth, more startups and consumers who now seem bored by what once excited them. Many U.S. shoppers have grown tired of buying Prada and Chanel suits and prefer to spend their money on experiences rather than clothes. Questions about fashion companies’ labor and environmental practices are leading to new policies, although some critics remain unconvinced. Fashion still relies on creativity, innovation and consumer attention, some of which comes from technology and some from celebrities. Here are some key takeaways: High-fashion brands must now compete with “fast fashion,” apparel sold on eBay and vintage sites. Risk factors for fashion companies include China’s growth slowdown, reduced global trade, Brexit, terrorist attacks and erratic commodity prices. Plus-size women are a growing segment of the market, yet critics say designers are ignoring them. Overview José Neves launched Farfetch during the global economic crisis of 2008, drawing more on his background in IT and software than a love of fashion. His idea: Allow small designers and fashion shops to sell their wares worldwide on a single online marketplace. The site will “fetch” fashion from far-off places. -

'Perfect Fit': Industrial Strategies, Textual Negotiations and Celebrity

‘Perfect Fit’: Industrial Strategies, Textual Negotiations and Celebrity Culture in Fashion Television Helen Warner Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) University of East Anglia School of Film and Television Studies Submitted July 2010 ©This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that no quotation from the thesis, nor any information derived therefrom, may be published without the author's prior, written consent. Helen Warner P a g e | 2 ABSTRACT According to the head of the American Costume Designers‟ Guild, Deborah Nadoolman Landis, fashion is emphatically „not costume‟. However, if this is the case, how do we approach costume in a television show like Sex and the City (1998-2004), which we know (via press articles and various other extra-textual materials) to be comprised of designer clothes? Once onscreen, are the clothes in Sex and the City to be interpreted as „costume‟, rather than „fashion‟? To be sure, it is important to tease out precise definitions of key terms, but to position fashion as the antithesis of costume is reductive. Landis‟ claim is based on the assumption that the purpose of costume is to tell a story. She thereby neglects to acknowledge that the audience may read certain costumes as fashion - which exists in a framework of discourses that can be located beyond the text. This is particularly relevant with regard to contemporary US television which, according to press reports, has witnessed an emergence of „fashion programming‟ - fictional programming with a narrative focus on fashion. -

Evolución, Tendencias Y Perspectivas De Futuro De La Publicidad De Moda En Revistas Especializadas

Trabajo Fin de Máster Evolución, tendencias y perspectivas de futuro de la publicidad de moda en revistas especializadas Alyona Dvornikova Tutor: Dr. Juan Miguel Monserrat Gauchi Máster Universitario en Comunicación e Industrias Creativas Junio de 2014 comincrea* Trabajo Fin de Máster COMINCREA* 2013 - 2014 Este documento es parte de mi trabajo para la obtención del título de Máster Universitario en Comunicación e Industrias Creativas de la Universidad de Alicante y no ha sido utilizado previamente (o simultáneamente) para la obtención de cualquier otro título o superación de asignaturas. Se trata de un trabajo original e inédito, producto de una investigación genuina, con indicación rigurosa de las fuentes que he utilizado, tanto bibliográficas como documentales o de otra naturaleza, en papel o en soporte digital. Doy mi consentimiento para que se archive este trabajo en la biblioteca universitaria del centro, donde se puede facilitar su consulta. Trabajo Fin de Máster COMINCREA* 2013 - 2014 A mi familia, Ucrania y a él, que amo tanto Quisiera agradecer a mi familia que me inspira, apoya y nunca pierde la fe en mí. Gracias a las dos Anas, a mis dos hermanas que llenan mi vida y me ayudan a sentirla con cada célula de mi cuerpo. Gracias a mi tierra natal, Ucrania, que me hizo así como soy ahora, que me ayuda siempre ir adelante hacia mis objetivos y nunca redirme. Gracias a él, una persona especial de mi vida, que me ayudó a encontrar mi punto de apoyo y con él ahora sé exactamente que un día moveré el mundo. Le agradezco muchísimo a mi quierido tutor, Juan Monserrat Gauchi. -

Gillian Laub CV 2021

Gillian Laub (b.1975, Chappaqua, New York) is a photographer and filmmaker based in New York. She graduated from the University of Wisconsin-Madison with a degree in comparative literature before studying photography at the International Center of Photography, where her love of visual storytelling and family narratives began. Laub’s first monograph, Testimony (Aperture 2007), began as a response to the media coverage during the second Intifada in the Middle East, and a desire to create a dialogue between apparent enemies. This work is comprised of portraits and testimonies from Israeli Jews, Israeli Arabs, Lebanese, and Palestinians all directly and indirectly affected by the complicated geopolitical context in which they lived. Laub spent over a decade working in Georgia exploring issues of lingering racism in the American South. This work became Laub’s first feature length, directed and produced, documentary film, Southern Rites that premiered on HBO in May 2015. Her monograph, Southern Rites (Damiani, 2015) and travelling exhibition by the same title came out in conjunction with the film and are being used for an educational outreach campaign, in schools and institutions across the country. Southern Rites was named one of the best photo books of 2015 by TIME, Smithsonian, Vogue, LensCulture, and American Photo. It was also nominated for a Lucie award and Humanitas award. "Riveting...In a calm, understated tone, Southern Rites digs deep to expose the roots that have made segregated proms and other affronts possible. Southern Rites is a portrait of the inequities that lead to disaster on the streets of cities like Baltimore and Ferguson, Mo.” - The New York Times Laub has been interviewed on NPR, CNN, MSNBC, Good Morning America, Times Talks and numerous others. -

Fashion and the First Ladies”

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: NEW YORK WOMEN IN FILM & TELEVISION AND FASHION GROUP INTERNATIONAL PRESENT “FASHION AND THE FIRST LADIES” An in-depth look at fashion as a communication tool throughout history and politics in celebration of Women’s History Month NEW YORK, NY – March 8, 2021 – New York Women in Film & Television (NYWIFT) and the Fashion Group International (FGI) are proud to present “Fashion and the First Ladies” on Friday, March 12, 2021 at 1 PM EST in celebration of Women’s History Month! In this hour-long virtual program, industry leaders Fernando Garcia (Co-Creative Director of Oscar De La Renta), Valerie Steele (Director and Chief Curator of The Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology), and Carson Poplin (Fashion Historian) will discuss the iconic looks from U.S. First Ladies of government in a candid conversation about how our First Ladies are fashion trend setters. The panel will explore how fashion plays a role and communicates in history, politics and contributes to the making or breaking of public policy. Archival images and current looks from recent First Ladies dressed by Oscar de la Renta will be featured. The conversation will be moderated by The Washington Post Senior Critic at Large, Robin Givhan. “The U.S. First Ladies have been at the forefront of social change, from Abigail Adams’s declaration to ‘remember the ladies’ to Michelle Obama’s advocacy for public health and education – and their fashion choices often played a critical role in establishing their personality, their message, and their power. NYWIFT is thrilled to dive deep into the role fashion plays in media and communications as we celebrate Women’s History – this month and every month,” said NYWIFT Executive Director Cynthia Lopez. -

Urban Representation in Fashion Magazines

Chair of Urban Studies and Social Research Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism Bauhaus-University Weimar Fashion in the City and The City in Fashion: Urban Representation in Fashion Magazines Doctoral dissertation presented in fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor philosophiae (Dr. phil.) Maria Skivko 10.03.1986 Supervising committee: First Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Frank Eckardt, Bauhaus-University, Weimar Second Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Stephan Sonnenburg, Karlshochschule International University, Karlsruhe Thesis Defence: 22.01.2018 Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................. 5 Thesis Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 6 Part I. Conceptual Approach for Studying Fashion and City: Theoretical Framework ........................ 16 Chapter 1. Fashion in the city ................................................................................................................ 16 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 16 1.1. Fashion concepts in the perspective ........................................................................................... 18 1.1.1. Imitation and differentiation ................................................................................................ 18 1.1.2. Identity -

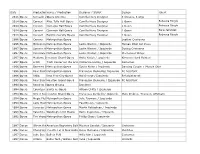

Date Production Name Venue / Production Designer / Stylist Design

Date ProductionVenue Name / Production Designer / Stylist Design Talent 2015 Opera Komachi atOpera Sekidrera America Camilla Huey Designer 3 dresses, 3 wigs 2014 Opera Concert Alice Tully Hall Opera Camilla Huey Designer 1 Gown Rebecca Ringle 2014 Opera Concert Carnegie Hall Opera Camilla Huey Designer 1 Gown Rebecca Ringle 2014 Opera Concert Carnegie Hall Opera Camilla Huey Designer 1 Gown Sara Jakubiak 2013 Opera Concert Bard University Opera Camilla Huey Designer 1 Gown Rebecca Ringle 1996 Opera Carmen Metropolitan Opera Leather Costumes 1996 Opera Midsummer'sMetropolitan Night's Dream Opera Leslie Weston / Izquierdo Human Pillar Set Piece 1997 Opera Samson & MetropolitanDelilah Opera Leslie Weston / Izquierdo Dyeing Costumes 1997 Opera Cerentola Metropolitan Opera Leslie Weston / Izquierdo Mechanical Wings 1997 Opera Madame ButterflyHouston Grand Opera Anita Yavich / Izquierdo Kimonos Hand Painted 1997 Opera Lillith Tisch Center for the Arts OperaCatherine Heraty / Izquierdo Costumes 1996 Opera Bartered BrideMetropolitan Opera Sylvia Nolan / Izquierdo Dancing Couple + Muscle Shirt 1996 Opera Four SaintsMetropolitan In Three Acts Opera Francesco Clemente/ Izquierdo FC Asssitant 1996 Opera Atilla New York City Opera Hal George / Izquierdo Refurbishment 1995 Opera Four SaintsHouston In Three Grand Acts Opera Francesco Clemente / Izquierdo FC Assistant 1994 Opera Requiem VariationsOpera Omaha Izquierdo 1994 Opera Countess MaritzaSanta Fe Opera Allison Chitty / Izquierdo 1994 Opera Street SceneHouston Grand Opera Francesca Zambello/ Izquierdo -

Congressional Overspeech

ARTICLES CONGRESSIONAL OVERSPEECH Josh Chafetz* Political theater. Spectacle. Circus. Reality show. We are constantly told that, whatever good congressional oversight is, it certainly is not those things. Observers and participants across the ideological and partisan spectrums use those descriptions as pejorative attempts to delegitimize oversight conducted by their political opponents or as cautions to their own allies of what is to be avoided. Real oversight, on this consensus view, is about fact-finding, not about performing for an audience. As a result, when oversight is done right, it is both civil and consensus-building. While plenty of oversight activity does indeed involve bipartisan attempts to collect information and use that information to craft policy, this Article seeks to excavate and theorize a different way of using oversight tools, a way that focuses primarily on their use as a mechanism of public communication. I refer to such uses as congressional overspeech. After briefly describing the authority, tools and methods, and consensus understanding of oversight in Part I, this Article turns to an analysis of overspeech in Part II. The three central features of overspeech are its communicativity, its performativity, and its divisiveness, and each of these is analyzed in some detail. Finally, Part III offers two detailed case studies of overspeech: the Senate Munitions Inquiry of the mid-1930s and the McCarthy and Army-McCarthy Hearings of the early 1950s. These case studies not only demonstrate the dynamics of overspeech in action but also illustrate that overspeech is both continuous across and adaptive to different media environments. Moreover, the case studies illustrate that overspeech can be used in the service of normatively good, normatively bad, and * Professor of Law, Georgetown University Law Center. -

Women's Studies

Women’s Studies proquest.com To talk to the sales department, contact us at 1-800-779-0137 or [email protected]. “Women’s history” is not confined to a discrete subdiscipline. Rather, every branch of history, from political and social to local and international, is also the history of women. But the roles and perspectives of women are frequently overlooked in the past struggles and triumphs that shape our modern lives. This can make it difficult for students and scholars to discover resources that illuminate these connections and permit fresh insights. Women’s history databases from ProQuest are thoughtfully curated by experts to overcome this challenge. Suffrage, reproductive rights, economic issues, intersectionality, sexual discrimination – these are just some of the many topics that can be explored in depth with ProQuest’s extensive, carefully selected Women’s History collections. The experiences, influences, and observations of women over time and around the world are brought to the forefront of interdisciplinary research and learning through materials such as organizational documents, domestic records, personal correspondence, books, videos, historical periodicals, newspapers, dissertations as well as literature and fashion publications. Table of Contents PRIMARY SOURCES........................................................................................... 3 ProQuest History Vault ........................................................................................................ 3 Women and Social Movements Library ......................................................................... -

Fashion Design in the 21St Century A

TECHNOLOGY AND CREATIVITY: FASHION DESIGN IN THE 21 ST CENTURY A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by MARY RUPPERT-STROESCU Dr. Jana Hawley, Dissertation Supervisor May 2009 © Copyright by Mary Ruppert-Stroescu 2009 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled TECHNOLOGY AND CREATIVITY: FASHION DESIGN IN THE 21 ST CENTURY Presented by Mary Ruppert-Stroescu, a candidate for the degree of doctor of philosophy and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. _______________________________ Dr. Kitty Dickerson _______________________________ Dr. Jana Hawley _______________________________ Dr. Laurel Wilson _______________________________ Dr. Julie Caplow I dedicate this dissertation to my sons, Matei and Ioan Stroescu, who are continuous sources of inspiration and joy. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my dissertation supervisor, Dr. Jana Hawley, for inspiring and challenging me without fail. I will remain eternally grateful as well to Dr. Laurel Wilson & Dr. Kitty Dickerson, for their patience, insight, and guidance. I must also recognize Dr. Jean Hamilton, whose courses I will never forget because her ability to communicate a passion for research sparked my path to this dissertation. Dr. Julie Caplow built upon the appreciation for qualitative research that began with Dr. Hamilton, and I thank her for her support. Without Peter Carman I would not have had a platform for connecting with the French industry interviewees. I thank my family for their support, and all those who took time from their professional obligations to discuss technology and creativity with me. -

Op in Vogue Elena Galleani D'agliano 2020

OP IN VOGUE ELENA GALLEANIELENA D’AGLIANO 2020 Op in Vogue Elena Galleani d’Agliano Op in Vogue Master Thesis by Elena Galleani d’Agliano Supervised by Jérémie Cerman Printed at Progetto Immagine, Torino MA Space and Communication HEAD Genève October 2019 Vorrei ringraziare il mio tutor Jérémie per avermi seguito in questi mesi, Sébastien e Laurence per il loro indispensabile aiuto al Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Oliver and Anna per avermi dato una mano con l’inglese, Alexandra e gli altri tutor per i loro incoraggiamenti e la mia famiglia per il loro instancabile supporto. 5 10 18 34 43 87 108 88 A glimse of the Sixties 90 The Optical Woman Portfolio 91 The diffusion of Architectural 64 prêt a porter Defining Op 44 The Guy visions in Mulas 18 92 Economic impli- fashion Bourdin’s elegance 67 Who are you, 34 Fashion pho- cations 11 Definition of The relation- 48 The youth quake William Klein? 21 tography in the 96 Basis for further Op Art according to Bailey Franco Rubar- ship with the Sixties 70 experimentations: 13 The influen- source 52 The female telli, the storyteller 36 Defining Op the Space Age Style ces Op art and emancipation throu- 74 Swinging with 27 photography 102 The heritage 108 Epilogue 14 Exhibitions its representation gh the lens of Hel- Ronald Traeger 83 Advertising mut Newton today 111 Bibliography and diffusion on Vogue 78 Others 57 Monumentality in Irving Penn 60 In the search of other worlds with Henry Clarke Prologue The Op Op Fashion Sociological Epilogue fashion photography implications 7 8 9 Prologue early sixty years ago, mum diffusion, 1965 and 1966.