Social Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indigenous Community Protocols for Bankstown Area Multicultural Network

INDIGENOUS COMMUNITY PROTOCOLS FOR BAMN MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE Practical protocols for working with the Indigenous Community of South West Sydney 1 Contents RESPECT, ACKNOWLEDGE, LISTEN Practical protocols for working with Indigenous communities in Western Sydney What are protocols? 1. Get To Know Your Indigenous Community Identity Diversity – Different rules for different community groups (there can sometimes be different groups within communities) 2. Consult Indigenous Reference Groups, Steering Committees and Boards 3. Get Permission The Local Community Elders Traditional Owners Ownership Copyright and Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property 4. Communicate Language Koori Time Report back and stay in touch 5. Ethics and Morals Confidentiality Integrity and trust 6. Correct Procedures Respect What to call people Traditional Welcome or Welcome to Country Acknowledging Traditional Owners Paying People Indigenous involvement Cross Cultural Training 7. Indigenous Organisations and Western Sydney contacts Major Indigenous Organisations Local Aboriginal Land Councils Indigenous Corporations/Community Organisations Indigenous Council, Community and Arts workers 8. Keywords to Remember 9. Other Protocol Resource Documents 2 What Are Protocols? Protocols can be classified as a set of rules, regulations, processes, procedures, strategies, or guidelines. Protocols are simply the ways in which you work with people, and communicate and collaborate with them appropriately. They are a guide to assist you with ways in which you can work, communicate and collaborate with the Indigenous community of Western Sydney. A wealth of Indigenous protocols documentation already exists (see Section 9), but to date the practice of following them is not widespread. Protocols are also standards of behaviour, respect and knowledge that need to be adopted. You might even think of them as a code of manners to observe, rather than a set of rules to obey. -

The Builders Labourers' Federation

Making Change Happen Black and White Activists talk to Kevin Cook about Aboriginal, Union and Liberation Politics Kevin Cook and Heather Goodall Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Cook, Kevin, author. Title: Making change happen : black & white activists talk to Kevin Cook about Aboriginal, union & liberation politics / Kevin Cook and Heather Goodall. ISBN: 9781921666728 (paperback) 9781921666742 (ebook) Subjects: Social change--Australia. Political activists--Australia. Aboriginal Australians--Politics and government. Australia--Politics and government--20th century. Australia--Social conditions--20th century. Other Authors/Contributors: Goodall, Heather, author. Dewey Number: 303.484 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover images: Kevin Cook, 1981, by Penny Tweedie (attached) Courtesy of Wildlife agency. Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc. is a part of the Australian Centre for Indigenous History, Research School of Social Sciences, The Australian National University and gratefully acknowledges the support of the School of History RSSS and the National Centre for Indigenous Studies, The Australian National -

Ntscorp Limited Annual Report 2010/2011 Abn 71 098 971 209

NTSCORP LIMITED ANNUAL REPORT 2010/2011 ABN 71 098 971 209 Contents 1 Letter of Presentation 2 Chairperson’s Report 4 CEO’s Report 6 NTSCORP’s Purpose, Vision & Values 8 The Company & Our Company Members 10 Executive Profiles 12 Management & Operational Structure 14 Staff 16 Board Committees 18 Management Committees 23 Corporate Governance 26 People & Facilities Management 29 Our Community, Our Service 30 Overview of NTSCORP Operations 32 Overview of the Native Title Environment in NSW 37 NTSCORP Performing the Functions of a Native Title Representative Body 40 Overview of Native Title Matters in NSW & the ACT in 2010-2011 42 Report of Performance by Matter 47 NTSCORP Directors’ Report NTSCORP LIMITED Letter OF presentation THE HON. JennY MacKlin MP Minister for Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Minister, RE: 2010–11 ANNUAL REPORT In accordance with the Commonwealth Government 2010–2013 General Terms and Conditions Relating to Native Title Program Funding Agreements I have pleasure in presenting the annual report for NTSCORP Limited which incorporates the audited financial statements for the financial year ended 30 June 2011. Yours sincerely, MicHael Bell Chairperson NTSCORP NTSCORP ANNUAL REPORT 10/11 – 1 CHAIrperson'S Report NTSCORP LIMITED CHAIRPERSON’S REPORT The Company looks forward to the completion of these and other ON beHalF OF THE directors agreements in the near future. NTSCORP is justly proud of its involvement in these projects, and in our ongoing work to secure and members OF NTSCORP, I the acknowledgment of Native Title for our People in NSW. Would liKE to acKnoWledGE I am pleased to acknowledge the strong working relationship with the NSW Aboriginal Land Council (NSWALC). -

Caring for Community

AH&MRC Tackling Tobacco and Chronic Conditions Conference 2016: CARING FOR COMMUNITY Crowne Plaza, Coogee Beach, 242 Arden Street, Coogee, Sydney Tuesday 3 May 2016 9.00am – 10.30am Master of Ceremony Nicole Turner Room Description Ocean View Delegates are asked to sign in to the conference on Level One before making their way Court to the Ocean View Court on the Lower Ground Level for the 9am Conference Opening. Opening address and plenary session Conference Opening A smoking ceremony and Welcome to Country, followed by a traditional dance performance. Room Description Oceanic Official Welcome Ballroom Sandra Bailey, CEO, Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council of NSW will welcome participants before introducing a video that provides an overview of the The AH&MRC Tackling Tobacco and Chronic Conditions Conference 2016: Caring for history and importance of Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services. Community is the first year the biennial chronic disease conference and annual A-TRAC symposiums have been combined. Aboriginal Communities Improving Aboriginal Health Report The Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council (AH&MRC) Lead author, Dr Megan Campbell will discuss key points and how the recent literature The AH&MRC is the peak representative body and voice of Aboriginal communities on health review Aboriginal Communities Improving Aboriginal Health Report can be used. in NSW. We represent, support and advocate for our members, the Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services (ACCHS) that deliver culturally appropriate comprehensive primary Launch: Living Longer Stronger Resource Kit health care, and their communities on Aboriginal health at state and national levels. David Kennedy & Megan Winkler from the Resource Kit Advisory Group will launch the chronic disease Living Longer Stronger Resource Kit and discuss why, who and AH&MRC Chronic Disease Program what it was developed for. -

Practical Protocols for Working with the Indigenous Community of Western Sydney

CCD_RAL_bk.qxd 15/7/03 3:04 PM Page 1 CCD_RAL_Final.qxd 15/7/03 3:06 PM Page 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project was assisted by the Government of NSW through the and The Federal Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body. Researched and Written by This document is a project of the Angelina Hurley Indigenous Program of Indigenous Program Manager Community Cultural Development New Community Cultural Development NSW South Wales (CCDNSW) Draft Review and Copyright Section by © Community Cultural Development NSW Terri Janke Ltd, 2003 Principle Solicitor Terri Janke and Company Suite 8 54 Moore St. Design and Printing by Liverpool NSW 2170 MLC Powerhouse Design Studio PO Box 512 April 2003 Liverpool RC 1871 Ph: (02) 9821 2210 Cover Art Work Fax: (02) 9821 3460 ‘You Can’t Have Our Spirituality Without Web: www.ccdnsw.org Our Political Reality’ by Indigenous Artist Gordon Hookey Internal Art Work ‘Men’s Ceremony’ by Indigenous Artist Adam Hill CCD_RAL_Final.qxd 15/7/03 5:05 PM Page 2 Contents RESPECT, ACKNOWLEDGE, LISTEN: Practical protocols for working with the Indigenous Community of Western Sydney . .3 Who are Community Cultural Development New South Wales (CCDNSW)? What is ccd? . .3 What Are Protocols? . .3 1. Get To Know Your Indigenous Community . .4 Identity . .5 Diversity - Different Rules For Different Groups . .6 2. Consult . .6 Indigenous Reference Groups, Steering Committees and Boards . .7 3. Get Permission . .8 The Local Community . .8 Elders . .8 Traditional Owners . .8 Ownership . .9 Copyright And Indigenous Cultural And Intellectual Property . .9 4. Communicate . .10 Language . .10 Koori Time . -

The Hearing, Ear Health and Language Services (HEALS) Project

INDIGENOUS HEALTH A case study of enhanced clinical care enabled by Aboriginal health research: the Hearing, EAr health and Language Services (HEALS) project Christian Young,1,2 Hasantha Gunasekera,3 Kelvin Kong,4,5 Alison Purcell,6 Sumithra Muthayya,7 Frank Vincent,8 Darryl Wright,9 Raylene Gordon,10 Jennifer Bell,11 Guy Gillor,8 Julie Booker,12 Peter Fernando,7 Deanna Kalucy,7 Simone Sherriff,7,13 Allison Tong,1,2 Carmen Parter,14 Sandra Bailey,15 Sally Redman,7 Emily Banks,7,16 Jonathan C. Craig1,2 he gap between Aboriginal and Abstract non-Aboriginal Australian’s health Toutcomes is well documented,1-4 Objective: To describe and evaluate Hearing EAr health and Language Services (HEALS), a New but there are relatively few examples of South Wales (NSW) health initiative implemented in 2013 and 2014 as a model for enhanced how service delivery can be enhanced, clinical services arising from Aboriginal health research. particularly in urban settings where most Methods: A case-study involving a mixed-methods evaluation of the origins and outcomes Aboriginal people live.5 Aboriginal families of HEALS, a collaboration among five NSW Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services experience greater barriers than other (ACCHS), the Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network, NSW Health, the Aboriginal Health and Australians when accessing health services Medical Research Council, and local service providers. Service delivery data was collected for many reasons including: insufficient, fortnightly; semi-structured interviews were conducted with healthcare providers and often inconsistent funding for community health services; economic hardship; limited caregivers of children who participated in HEALS. -

The Aboriginal Health & Medical Research Council Of

The Aboriginal Health & Medical Research Council of NSW Annual Report 2012-13 © 2013 Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council of New South Wales This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced either in whole or part without the prior written approval of the Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council of New South Wales (AH&MRC). ISSN 2200-9906 The Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council of New South Wales Level 3, 66 Wentworth Ave, Surry Hills NSW 2010 Phone: +61 2 9212 4777 Fax: +61 2 9212 7211 Postal Address: PO Box 1565, Strawberry Hills 2012 Web: www.ahmrc.org.au [ABN 66 085 654 397] Edited by Matthew Rodgers – Media & Communications Coordinator, AH&MRC Design by Publicstyle Web: publicstyle.com.au About the cover Cover art: Steve Morgan About the artist: Steve Morgan is a Gamilaraay man from Walgett, North South Wales. Steve is an emerging artist now living in Sydney. His passions include music, art and being around the mob. About the artwork: The Cycle of Life No. 3 The four corners represent the four seasons. Each season has a specific role in the growth cycle. The circle in the centre depicts a seed that is affected by the four seasons. The community is always present and needs to be nurtured and strengthened throughout the four seasons. The AH&MRC wishes to advise people of Aboriginal descent that this document may contain images of persons now deceased. Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council of New South Wales Annual Report 2012-13 Contents -

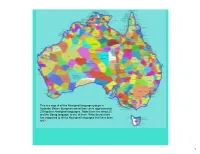

This Is a Map of All the Aboriginal Language Groups in Australia

This is a map of all the Aboriginal language groups in Australia. Before European arrival there were approximately 250 spoken Aboriginal languages. Today there are about 25, and the Darug language is one of them. What do you think has happened to all the Aboriginal languages that have been lost? 1 Do you speak my language? This lesson: Learning to speak some of the Darug language Aunty Val Aurisch Speaking at The Gully Culture Camp 2010 Picture soured 20 April 2011 from: http://www.livingcountry.com.au/gallery.cfm 2 Listen to me speak the Darug language Richard Green helps keep his language alive and strong by teaching it to students at Chifley College, Dunheved Campus and at Doonside Technical High School. Listen to Richard Green talk about his language in Darug (and English) by clicking on the picture of Richard. This will take you to to the William Dawes website where you can listen to an mp3 file. Richard Green Picture: Copyright 2009 The Hills Shire Council 3 Can you speak Darug language? Click the Darug name and drag it to the 'Word' column. Select the check button to find out how you went! Words sourced from Yarramundi Kids website on 20 April 2011: http://yarramundikids.tv/yarramundikids/howdoyousay.html 4 A shared historyA brief introduction to Lieutenant William Dawes Lieutenant William Dawes (1762-1836) was known as an officer of marines, scientist and administrator, yet it is his interest in studying the local Eora (Darug) people that tells the story of a shared history. Dawes developed a friendship with a young Darug girl who was about fifteen years old. -

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples Education Policy

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples Education Policy 1. Scope This policy is applicable to Holmes Institute Pty Ltd, Holmes Colleges Queensland Pty Ltd, Holmes Colleges Sydney Pty Ltd, Headmasters Academy Pty Ltd and Holmes Commercial Colleges (Melbourne) Ltd, collectively known as the Holmes Education Group (Holmes) and to students and potential students applying for entry into a course of study at Holmes. 2. Purpose 2.1 This policy provides Holmes’ principles, commitments and objectives for developing and delivering education to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. 2.2 This policy has been developed, having regard to a number of contemporary reports. These include Australia’s national and international obligations including the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, endorsed by the Australian Government; the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Education Policy; Universities Australia Indigenous Strategy 2017 – 2020; and the recommendations in the Review of Higher Education Access and Outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People Final Report 2012. 2.3 Holmes is committed to providing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with access to educational opportunities with Holmes. While the majority of Holmes’ students are international students, it is possible that Holmes will, in future expand its student body to include an increasing number of domestic students, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. 3. Definitions 3.1 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural competence and capabilities means student and staff knowledge and understanding of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples' cultures, histories, contemporary realities and protocols, and proficiency to engage and work effectively in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples' contexts and expectations (adapted from Universities Australia, Guiding Principles for Developing Indigenous Cultural Competency in Australian Universities, October 2011). -

Yurunnhang Bungil Nyumba: Infusing Aboriginal Ways of Being Into Teaching Practice in Australia

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2020 Yurunnhang Bungil Nyumba: Infusing Aboriginal ways of being into teaching practice in Australia Lisa Buxton The University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Education Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Buxton, L. (2020). Yurunnhang Bungil Nyumba: Infusing Aboriginal ways of being into teaching practice in Australia (Doctor of Education). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/248 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Yurunnhang Bungil Nyumba: Infusing Aboriginal ways of being into teaching practice in Australia Lisa Maree Buxton MPhil, MA, GDip Secondary Ed, GDip Aboriginal Ed, BA. Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Doctor of Education School of Education Sydney Campus January, 2020 Acknowledgement of Country Protocols The protocol for introducing oneself to other Indigenous people is to provide information about one’s cultural location, so that connection can be made on political, cultural and social grounds and relations established. (Moreton-Robinson, 2000, pp. xv) I would like firstly to acknowledge with respect Country itself, as a knowledge holder, and the ancients and ancestors of the country in which this study was conducted, Gadigal, Bidjigal and Dharawal of Eora Country. -

Aboriginal Design Principles

WAGGA WAGGA SPECIAL ACTIVATION PRECINCT WIRADJURI COUNTRY ABORIGINAL DESIGN PRINCIPLES This document acknowledges the elders, past and present, of the Wiradjuri people as the traditional owners of Wagga Wagga and the lands knowledge. / Explorer Mitchell (1839) described “a beautiful plain; covered with shining verdure [lush green vegetation] and ornamented with trees… gave the country the appearance of an extensive park” Contents Document produced by Michael Hromek WSP Australia Pty Ltd. 01. Wiradjuri Country Descended from the Budawang tribe of the Yuin nation, Michael is currently working at WSP, doing a PhD in architecture People and Design and teaches it at the University of Technology Sydney in the Bachelor of Design in Architecture. [email protected] 02. Aboriginal Planning Principles Research by Sian Hromek (Yuin) Graphic design by Sandra Palmer, WSP 03. Project Site Application of Aboriginal Planning and Design Principles 04. Project Examples Examples of Indigenous planning and design applied to projects of similar scope 05. Indigenous participation strategy Engaging Community through co-design strategies Image above: Sennelier Watercolour - Light Yellow Ochre (254) Please note: In order to highlight the use of Aboriginal Design Principles, this document may contain examples from other Aboriginal Countries. 01 WIRADJURI COUNTRY - 1 - Indigenous specialist services When our Country is acknowledged and returned to us, Aboriginal design principles it completes our songline, makes us feel culturally proud, Indigenous led/ Indigenous people (designers, elders etc) and strengthens our identity and belonging. should be leading or co-leading the Indigenous elements in the design. Wurundjeri Elder, Annette Xiberras. Community involvement/ The local Indigenous community to be engaged in this process, can we use their patterns? Can they design patterns for the project? Appropriate use of Indigenous design/ All Indigenous Indigenous design statement design elements must be approved of by involved Indigenous people / community / elders. -

Working with Aboriginal People and Communities

Produced by Aboriginal Services Branch in consultation with the Aboriginal Reference Group NSW Department of Community Services 4-6 Cavill Avenue Ashfield NSW 2131 Phone (02) 9716 2222 February 2009 ISBN 1 74190 097 2 www.community.nsw.gov.au A number of NSW Department of As Aboriginal people are the Community Service (Community original inhabitants of NSW; and Services) regions as well as several as the NSW Government only has other government agencies have a specific charter of service to the created their own practice guides people of NSW, this document for working with Aboriginal people refers only to Aboriginal people. and communities. In developing References to Torres Strait Islander this practice resource, we have people will be specifically stated combined the best elements of where relevant. It is important existing practices to develop to remember that Aboriginal and a resource that provides a Torres Strait Islander cultures are consistent approach to working very different, with their own with Aboriginal people and unique histories, beliefs and values. communities.1 It is respectful to recognise their separate identities. Community The information and practice tips Services recognise that Torres contained in this document are Strait Islander people are among generalisations and do not reflect the First Nations of Australia the opinions of all Aboriginal and represent a part of our client people and communities in NSW. and staff base. The Department’s There may be exceptions to the Aboriginal programs and services information