Reconstructing Aboriginal Economy and Society: the New South Wales

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indigenous Community Protocols for Bankstown Area Multicultural Network

INDIGENOUS COMMUNITY PROTOCOLS FOR BAMN MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE Practical protocols for working with the Indigenous Community of South West Sydney 1 Contents RESPECT, ACKNOWLEDGE, LISTEN Practical protocols for working with Indigenous communities in Western Sydney What are protocols? 1. Get To Know Your Indigenous Community Identity Diversity – Different rules for different community groups (there can sometimes be different groups within communities) 2. Consult Indigenous Reference Groups, Steering Committees and Boards 3. Get Permission The Local Community Elders Traditional Owners Ownership Copyright and Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property 4. Communicate Language Koori Time Report back and stay in touch 5. Ethics and Morals Confidentiality Integrity and trust 6. Correct Procedures Respect What to call people Traditional Welcome or Welcome to Country Acknowledging Traditional Owners Paying People Indigenous involvement Cross Cultural Training 7. Indigenous Organisations and Western Sydney contacts Major Indigenous Organisations Local Aboriginal Land Councils Indigenous Corporations/Community Organisations Indigenous Council, Community and Arts workers 8. Keywords to Remember 9. Other Protocol Resource Documents 2 What Are Protocols? Protocols can be classified as a set of rules, regulations, processes, procedures, strategies, or guidelines. Protocols are simply the ways in which you work with people, and communicate and collaborate with them appropriately. They are a guide to assist you with ways in which you can work, communicate and collaborate with the Indigenous community of Western Sydney. A wealth of Indigenous protocols documentation already exists (see Section 9), but to date the practice of following them is not widespread. Protocols are also standards of behaviour, respect and knowledge that need to be adopted. You might even think of them as a code of manners to observe, rather than a set of rules to obey. -

The Builders Labourers' Federation

Making Change Happen Black and White Activists talk to Kevin Cook about Aboriginal, Union and Liberation Politics Kevin Cook and Heather Goodall Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Cook, Kevin, author. Title: Making change happen : black & white activists talk to Kevin Cook about Aboriginal, union & liberation politics / Kevin Cook and Heather Goodall. ISBN: 9781921666728 (paperback) 9781921666742 (ebook) Subjects: Social change--Australia. Political activists--Australia. Aboriginal Australians--Politics and government. Australia--Politics and government--20th century. Australia--Social conditions--20th century. Other Authors/Contributors: Goodall, Heather, author. Dewey Number: 303.484 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover images: Kevin Cook, 1981, by Penny Tweedie (attached) Courtesy of Wildlife agency. Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc. is a part of the Australian Centre for Indigenous History, Research School of Social Sciences, The Australian National University and gratefully acknowledges the support of the School of History RSSS and the National Centre for Indigenous Studies, The Australian National -

Re-Awakening Languages: Theory and Practice in the Revitalisation Of

RE-AWAKENING LANGUAGES Theory and practice in the revitalisation of Australia’s Indigenous languages Edited by John Hobson, Kevin Lowe, Susan Poetsch and Michael Walsh Copyright Published 2010 by Sydney University Press SYDNEY UNIVERSITY PRESS University of Sydney Library sydney.edu.au/sup © John Hobson, Kevin Lowe, Susan Poetsch & Michael Walsh 2010 © Individual contributors 2010 © Sydney University Press 2010 Reproduction and Communication for other purposes Except as permitted under the Act, no part of this edition may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or communicated in any form or by any means without prior written permission. All requests for reproduction or communication should be made to Sydney University Press at the address below: Sydney University Press Fisher Library F03 University of Sydney NSW 2006 AUSTRALIA Email: [email protected] Readers are advised that protocols can exist in Indigenous Australian communities against speaking names and displaying images of the deceased. Please check with local Indigenous Elders before using this publication in their communities. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Re-awakening languages: theory and practice in the revitalisation of Australia’s Indigenous languages / edited by John Hobson … [et al.] ISBN: 9781920899554 (pbk.) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Aboriginal Australians--Languages--Revival. Australian languages--Social aspects. Language obsolescence--Australia. Language revival--Australia. iv Copyright Language planning--Australia. Other Authors/Contributors: Hobson, John Robert, 1958- Lowe, Kevin Connolly, 1952- Poetsch, Susan Patricia, 1966- Walsh, Michael James, 1948- Dewey Number: 499.15 Cover image: ‘Wiradjuri Water Symbols 1’, drawing by Lynette Riley. Water symbols represent a foundation requirement for all to be sustainable in their environment. -

Country-Pensioner-Excursion-Map.Pdf

Country Pensioner Excursion Country Pensioner Excursion tickets do not apply in this area. Tweed Heads South Tweed Heads Chinderah Please use the standard NSW TrainLink tickets. Murwillumbah Kingscliff Bogangar Burringbar Hastings Point Pottsville Mooball NEW Northern Rivers Billinudgel SOUTH Ocean Shores QUEENSLAND Brunswick Heads WALES Kyogle Mullumbimby LismoreLismoreBexhill TownClunesBinnaBangalow Burra Byron Bay Suffolk Park Casino Eltham Lennox Head Tenterfield Ballina Ballina West Goonellabah Wardell Bolivia Wollongbar Alstonville Broadwater Evans Head Deepwater Woodburn Iluka Chatsworth Woombah Dundee Island Clarence River Moree TownBiniguy GravesendWarialda DelungraMount RussellInverell Glen Innes Maclean turnoff Yamba Lightning Ridge North West Moree Gibraltar Range Tyndale Warialda Rail Gilgai Cowper Yamba West Glencoe Palmers Island Jackadgery Ulmarra Bellata Bingara Tingha Grafton Bourke Brewarrina Llangothlin Walgett Cobbadah Bundarra Burren Wee Waa Junction Guyra Coffs Harbour Narrabri Barraba Yarrowyck Northern Tablelands Sawtell Upper Manilla Gongolgon Urunga Upper West Byrock Coonamble Armidale Manilla Uralla Nambucca Heads Bendemere Attunga North Macksville Boggabri Moonbi Walcha Baradine Coast Eungai Walcha Road Long Flat Coolabah Gulargambone Mullaley Kempsey Kootingal Hastings River Gunnedah Wauchope Coonabarabran Port Macquarie Girilambone Carroll Tamworth Somerton Kendall Gilgandra Werris Creek Wilcannia Emmdale Cobar Boppy MountainHermidale Binnaway Taree Nyngan Quirindi Wingham Mendooran Coolah Willow Tree Warren -

Indigenous Poems - Oodgeroo Noonuccal INTRODUCTION

Classic Australian literature: lessons for life Suitable for Grades 7-10 Indigenous Poems - Oodgeroo Noonuccal INTRODUCTION The indigenous poetry of Oodgeroo Noonuccal is significant in the history of Australian culture. The political and cultural themes of dispossession and cultural divides are as relevant now as the time in which they were written. Students will examine two different styles of poetry, their structure, style and historical context; from their understanding of contemporary issues they will create texts, design visual elements of story, research local history and create biographical articles. A variety of texts are available as resources including radio interview, historical archives, poetry websites and youtube clips. Included are poetry analysis worksheets, vocabulary activities and suggested summative and formative assessment. POEMS ‘We are going ’[available online at http://www.poetrylibrary.edu.au/poets/noonuccal-oodgeroo ] ‘No more boomerang’ This poem is read aloud to the indigenous music of the band ‘coloured stone’ http://youtu.be/codU1Ei2Etg] Summary Oodgeroo Noonuccal (formerly known as Kath walker ) was the first indigenous female poet to have her works published in 1964 to great success as the title We are going. Awarded the OBE in 1970 she famously returned the honour in 1987 in protest of the Bicentennial Celebrations Australia Day 1988. Born on North Stradbroke Island Minjerribah she worked in domestic service in Brisbane while raising two children. She returned to Minjerribah as a ‘grandmother’ and educator -

Caring for Community

AH&MRC Tackling Tobacco and Chronic Conditions Conference 2016: CARING FOR COMMUNITY Crowne Plaza, Coogee Beach, 242 Arden Street, Coogee, Sydney Tuesday 3 May 2016 9.00am – 10.30am Master of Ceremony Nicole Turner Room Description Ocean View Delegates are asked to sign in to the conference on Level One before making their way Court to the Ocean View Court on the Lower Ground Level for the 9am Conference Opening. Opening address and plenary session Conference Opening A smoking ceremony and Welcome to Country, followed by a traditional dance performance. Room Description Oceanic Official Welcome Ballroom Sandra Bailey, CEO, Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council of NSW will welcome participants before introducing a video that provides an overview of the The AH&MRC Tackling Tobacco and Chronic Conditions Conference 2016: Caring for history and importance of Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services. Community is the first year the biennial chronic disease conference and annual A-TRAC symposiums have been combined. Aboriginal Communities Improving Aboriginal Health Report The Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council (AH&MRC) Lead author, Dr Megan Campbell will discuss key points and how the recent literature The AH&MRC is the peak representative body and voice of Aboriginal communities on health review Aboriginal Communities Improving Aboriginal Health Report can be used. in NSW. We represent, support and advocate for our members, the Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services (ACCHS) that deliver culturally appropriate comprehensive primary Launch: Living Longer Stronger Resource Kit health care, and their communities on Aboriginal health at state and national levels. David Kennedy & Megan Winkler from the Resource Kit Advisory Group will launch the chronic disease Living Longer Stronger Resource Kit and discuss why, who and AH&MRC Chronic Disease Program what it was developed for. -

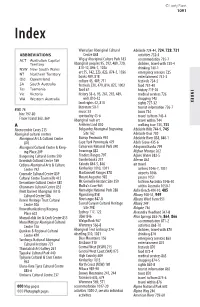

Australia-15-Index.Pdf

© Lonely Planet 1091 Index Warradjan Aboriginal Cultural Adelaide 724-44, 724, 728, 731 ABBREVIATIONS Centre 848 activities 732-3 ACT Australian Capital Wigay Aboriginal Culture Park 183 accommodation 735-7 Territory Aboriginal peoples 95, 292, 489, 720, children, travel with 733-4 NSW New South Wales 810-12, 896-7, 1026 drinking 740-1 NT Northern Territory art 55, 142, 223, 823, 874-5, 1036 emergency services 725 books 489, 818 entertainment 741-3 Qld Queensland culture 45, 489, 711 festivals 734-5 SA South Australia festivals 220, 479, 814, 827, 1002 food 737-40 Tas Tasmania food 67 history 719-20 INDEX Vic Victoria history 33-6, 95, 267, 292, 489, medical services 726 WA Western Australia 660, 810-12 shopping 743 land rights 42, 810 sights 727-32 literature 50-1 tourist information 726-7 4WD 74 music 53 tours 734 hire 797-80 spirituality 45-6 travel to/from 743-4 Fraser Island 363, 369 Aboriginal rock art travel within 744 A Arnhem Land 850 walking tour 733, 733 Abercrombie Caves 215 Bulgandry Aboriginal Engraving Adelaide Hills 744-9, 745 Aboriginal cultural centres Site 162 Adelaide Oval 730 Aboriginal Art & Cultural Centre Burrup Peninsula 992 Adelaide River 838, 840-1 870 Cape York Penninsula 479 Adels Grove 435-6 Aboriginal Cultural Centre & Keep- Carnarvon National Park 390 Adnyamathanha 799 ing Place 209 Ewaninga 882 Afghan Mosque 262 Bangerang Cultural Centre 599 Flinders Ranges 797 Agnes Water 383-5 Brambuk Cultural Centre 569 Gunderbooka 257 Aileron 862 Ceduna Aboriginal Arts & Culture Kakadu 844-5, 846 air travel Centre -

Four Stories: the Last Killer in Eden

Current Narratives Volume 1 Issue 4 Literary Journalism Special Issue Article 9 December 2014 Four Stories: The Last Killer in Eden Jake Evans University of Wollongong Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/currentnarratives Recommended Citation Evans, Jake, Four Stories: The Last Killer in Eden, Current Narratives, 4, 2014, 68-75. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/currentnarratives/vol1/iss4/9 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Four Stories: The Last Killer in Eden Abstract The Last Killer in Eden: one of four stories published in Current Narratives, 4, 2014. This journal article is available in Current Narratives: https://ro.uow.edu.au/currentnarratives/vol1/iss4/9 Evans: Four Stories: The Last Killer in Eden The Last Killer in Eden Jake Evans University of Wollongong1 Whale off the Eden Coast. Image: Peter Whiter 1 Jake Evans is a final year Bachelor of Journalism student at the University of Wollongong, where he is also part-time Managing Editor, UOW TV. Contact: [email protected] Published by Research Online, 2014 1 Current Narratives, Vol. 1, Iss. 4 [2014], Art. 9 Current Narratives 4: 2014 “Is it Peter, or Pete?” He looks at me and smiles through his white beard. “Pete. I always say when I’m called Peter I’m in trouble.” He returns to dislodging the Grey Duck from the trailer. He shimmies the raft into the water of the bay and the grey rubber hits with a slap. -

Aboriginal Totems

EXPLORING WAYS OF KNOWING, PROTECTING & ACKNOWLEDGING ABORIGINAL TOTEMS ACROSS THE EUROBODALLA SHIRE FAR SOUTH COAST, NSW Prepared by Susan Dale Donaldson Environmental & Cultural Services Prepared for The Eurobodalla Shire Council Aboriginal Advisory Committee FINAL REPORT 2012 THIS PROJECT WAS JOINTLY FUNDED BY COPYRIGHT AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF INDIGNEOUS CULTURAL & INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHTS Eurobodalla Shire Council, Individual Indigenous Knowledge Holders and Susan Donaldson. The Eurobodalla Shire Council acknowledges the cultural and intellectual property rights of the Indigenous knowledge holders whose stories are featured in this report. Use and reference of this material is allowed for the purposes of strategic planning, research or study provided that full and proper attribution is given to the individual Indigenous knowledge holder/s being referenced. Materials cited from the Australian Institute for Aboriginal and Islander Studies [AIATSIS] ‘South Coast Voices’ collections have been used for research purposes. These materials are not to be published without further consent, which can be gained through the AIATSIS. DISCLAIMER Information contained in this report was understood by the authors to be correct at the time of writing. The authors apologise for any omissions or errors. ACKNOWLEDMENTS The Eurobodalla koori totems project was made possible with funding from the NSW Heritage Office. The Eurobodalla Aboriginal Advisory Committee has guided this project with the assistance of Eurobodalla Shire Council staff - Vikki Parsley, Steve Picton, Steve Halicki, Lane Tucker, Shannon Burt and Eurobodalla Shire Councillors Chris Kowal and Graham Scobie. A special thankyou to Mike Crowley for his wonderful images of the Black Duck [including front cover], to Preston Cope and his team for providing advice on land tenure issues and to Paula Pollock for her work describing the black duck from a scientific perspective and advising on relevant legislation. -

Water Research Laboratory

Water Research Laboratory Never Stand Still Faculty of Engineering School of Civil and Environmental Engineering Eurobodalla Coastal Hazard Assessment WRL Technical Report 2017/09 October 2017 by I R Coghlan, J T Carley, A J Harrison, D Howe, A D Short, J E Ruprecht, F Flocard and P F Rahman Project Details Report Title Eurobodalla Coastal Hazard Assessment Report Author(s) I R Coghlan, J T Carley, A J Harrison, D Howe, A D Short, J E Ruprecht, F Flocard and P F Rahman Report No. 2017/09 Report Status Final Date of Issue 16 October 2017 WRL Project No. 2014105.01 Project Manager Ian Coghlan Client Name 1 Umwelt Australia Pty Ltd Client Address 1 75 York Street PO Box 3024 Teralba NSW 2284 Client Contact 1 Pam Dean-Jones Client Name 2 Eurobodalla Shire Council Client Address 2 89 Vulcan Street PO Box 99 Moruya NSW 2537 Client Contact 2 Norman Lenehan Client Reference ESC Tender IDs 216510 and 557764 Document Status Version Reviewed By Approved By Date Issued Draft J T Carley G P Smith 9 June 2017 Final Draft J T Carley G P Smith 1 September 2017 Final J T Carley G P Smith 16 October 2017 This report was produced by the Water Research Laboratory, School of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of New South Wales for use by the client in accordance with the terms of the contract. Information published in this report is available for release only with the permission of the Director, Water Research Laboratory and the client. It is the responsibility of the reader to verify the currency of the version number of this report. -

Practical Protocols for Working with the Indigenous Community of Western Sydney

CCD_RAL_bk.qxd 15/7/03 3:04 PM Page 1 CCD_RAL_Final.qxd 15/7/03 3:06 PM Page 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project was assisted by the Government of NSW through the and The Federal Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body. Researched and Written by This document is a project of the Angelina Hurley Indigenous Program of Indigenous Program Manager Community Cultural Development New Community Cultural Development NSW South Wales (CCDNSW) Draft Review and Copyright Section by © Community Cultural Development NSW Terri Janke Ltd, 2003 Principle Solicitor Terri Janke and Company Suite 8 54 Moore St. Design and Printing by Liverpool NSW 2170 MLC Powerhouse Design Studio PO Box 512 April 2003 Liverpool RC 1871 Ph: (02) 9821 2210 Cover Art Work Fax: (02) 9821 3460 ‘You Can’t Have Our Spirituality Without Web: www.ccdnsw.org Our Political Reality’ by Indigenous Artist Gordon Hookey Internal Art Work ‘Men’s Ceremony’ by Indigenous Artist Adam Hill CCD_RAL_Final.qxd 15/7/03 5:05 PM Page 2 Contents RESPECT, ACKNOWLEDGE, LISTEN: Practical protocols for working with the Indigenous Community of Western Sydney . .3 Who are Community Cultural Development New South Wales (CCDNSW)? What is ccd? . .3 What Are Protocols? . .3 1. Get To Know Your Indigenous Community . .4 Identity . .5 Diversity - Different Rules For Different Groups . .6 2. Consult . .6 Indigenous Reference Groups, Steering Committees and Boards . .7 3. Get Permission . .8 The Local Community . .8 Elders . .8 Traditional Owners . .8 Ownership . .9 Copyright And Indigenous Cultural And Intellectual Property . .9 4. Communicate . .10 Language . .10 Koori Time . -

FF Directory

Directory WFF (World Flora Fauna Program) - Updated 30 November 2012 Directory WorldWide Flora & Fauna - Updated 30 November 2012 Release 2012.06 - by IK1GPG Massimo Balsamo & I5FLN Luciano Fusari Reference Name DXCC Continent Country FF Category 1SFF-001 Spratly 1S AS Spratly Archipelago 3AFF-001 Réserve du Larvotto 3A EU Monaco 3AFF-002 Tombant à corail des Spélugues 3A EU Monaco 3BFF-001 Black River Gorges 3B8 AF Mauritius I. 3BFF-002 Agalega is. 3B6 AF Agalega Is. & St.Brandon I. 3BFF-003 Saint Brandon Isls. (aka Cargados Carajos Isls.) 3B7 AF Agalega Is. & St.Brandon I. 3BFF-004 Rodrigues is. 3B9 AF Rodriguez I. 3CFF-001 Monte-Rayses 3C AF Equatorial Guinea 3CFF-002 Pico-Santa-Isabel 3C AF Equatorial Guinea 3D2FF-001 Conway Reef 3D2 OC Conway Reef 3D2FF-002 Rotuma I. 3D2 OC Conway Reef 3DAFF-001 Mlilvane 3DA0 AF Swaziland 3DAFF-002 Mlavula 3DA0 AF Swaziland 3DAFF-003 Malolotja 3DA0 AF Swaziland 3VFF-001 Bou-Hedma 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-002 Boukornine 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-003 Chambi 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-004 El-Feidja 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-005 Ichkeul 3V AF Tunisia National Park, UNESCO-World Heritage 3VFF-006 Zembraand Zembretta 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-007 Kouriates Nature Reserve 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-008 Iles de Djerba 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-009 Sidi Toui 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-010 Tabarka 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-011 Ain Chrichira 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-012 Aina Zana 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-013 des Iles Kneiss 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-014 Serj 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-015 Djebel Bouramli 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-016 Djebel Khroufa 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-017 Djebel Touati 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-018 Etella Natural 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-019 Grotte de Chauve souris d'El Haouaria 3V AF Tunisia National Park, UNESCO-World Heritage 3VFF-020 Ile Chikly 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-021 Kechem el Kelb 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-022 Lac de Tunis 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-023 Majen Djebel Chitane 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-024 Sebkhat Kelbia 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-025 Tourbière de Dar.